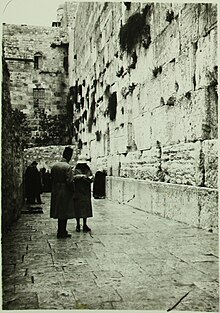

حائط البراق

( Western Wall )

The Western Wall (Hebrew: הַכּוֹתֶל הַמַּעֲרָבִי, romanized: HaKotel HaMa'aravi, lit. 'the western wall', often shortened to the Kotel or Kosel), known in the West as the Wailing Wall, and in Islam as the Buraq Wall (Arabic: حَائِط ٱلْبُرَاق, Ḥā'iṭ al-Burāq ['ħaːʔɪtˤ albʊ'raːq]), is a portion of ancient limestone wall in the Old City of Jerusalem that forms part of the larger retaining wall of the hill known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount. Just over half the wall's total height, including its 17 courses located below street level, dates from the end of the Second Temple period, and is believed to have been begun by Herod the Great. The very large stone blocks of the lower courses are Herodian, the courses of medium-siz...Read more

The Western Wall (Hebrew: הַכּוֹתֶל הַמַּעֲרָבִי, romanized: HaKotel HaMa'aravi, lit. 'the western wall', often shortened to the Kotel or Kosel), known in the West as the Wailing Wall, and in Islam as the Buraq Wall (Arabic: حَائِط ٱلْبُرَاق, Ḥā'iṭ al-Burāq ['ħaːʔɪtˤ albʊ'raːq]), is a portion of ancient limestone wall in the Old City of Jerusalem that forms part of the larger retaining wall of the hill known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount. Just over half the wall's total height, including its 17 courses located below street level, dates from the end of the Second Temple period, and is believed to have been begun by Herod the Great. The very large stone blocks of the lower courses are Herodian, the courses of medium-sized stones above them were added during the Umayyad period, while the small stones of the uppermost courses are of more recent date, especially from the Ottoman period.

The Western Wall plays an important role in Judaism due to its proximity to the Temple Mount. Because of the Temple Mount entry restrictions, the Wall is the holiest place where Jews are permitted to pray outside the previous Temple Mount platform, as the presumed site of the Holy of Holies, the most sacred site in the Jewish faith, lies just behind it. The original, natural, and irregular-shaped Temple Mount was gradually extended to allow for an ever-larger Temple compound to be built at its top. The earliest source mentioning this specific site as a place of Jewish worship is from the 17th century. The term Western Wall and its variations are mostly used in a narrow sense for the section of the wall used for Jewish prayer and called the "Wailing Wall", referring to the practice of Jews weeping at the site. During the period of Christian Roman rule over Jerusalem (ca. 324–638), Jews were completely barred from Jerusalem except on Tisha B'Av, the day of national mourning for the Temples. The term "Wailing Wall" has historically been used mainly by Christians, with use by Jews becoming marginal. In a broader sense, "Western Wall" can refer to the entire 488-metre-long (1,601 ft) retaining wall on the western side of the Temple Mount. The classic portion now faces a large plaza in the Jewish Quarter, near the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, while the rest of the wall is concealed behind structures in the Muslim Quarter, with the small exception of an 8-metre (26 ft) section, the so-called "Little Western Wall" or "Small Wailing Wall". This segment of the western retaining wall derives particular importance from having never been fully obscured by medieval buildings, and displaying much of the original Herodian stonework. In religious terms, the "Little Western Wall" is presumed to be even closer to the Holy of Holies and thus to the "presence of God" (Shechina), and the underground Warren's Gate, which has been out of reach for Jews from the 12th century till its partial excavation in the 20th century.

The Western Wall constitutes the western border of al-Haram al-Sharif ("the Noble Sanctuary"), or the Al-Aqsa compound. It is believed to be the site where the Islamic Prophet Muhammad tied his winged steed, the Burāq, on his Night Journey to Jerusalem before ascending to paradise. While the wall was considered an integral part of the Haram esh-Sharif and waqf property of the Moroccan Quarter under Muslim rule, a right of Jewish prayer and pilgrimage has long existed as part of the Status Quo. This position was confirmed in a 1930 international commission during the British Mandate period.

With the rise of the Zionist movement in the early 20th century, the wall became a source of friction between the Jewish and Muslim communities, the latter being worried that the wall could be used to further Jewish claims to the Temple Mount and thus Jerusalem. During this period outbreaks of violence at the foot of the wall became commonplace, with a particularly deadly riot in 1929 in which 133 Jews and 116 Arabs were killed, with many more people injured. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War the eastern portion of Jerusalem was occupied by Jordan. Under Jordanian control Jews were completely expelled from the Old City including the Jewish Quarter, and Jews were barred from entering the Old City for 19 years, effectively banning Jewish prayer at the site of the Western Wall. This period ended on June 10, 1967, when Israel gained control of the site following the Six-Day War. Three days after establishing control over the Western Wall site, the Moroccan Quarter was bulldozed by Israeli authorities to create space for what is now the Western Wall plaza.

Engraving, 1850 by Rabbi Joseph Schwarz

Engraving, 1850 by Rabbi Joseph SchwarzAccording to the Hebrew Bible, Solomon's Temple was built atop what is known as the Temple Mount in the 10th century BCE and destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE,[1] and the Second Temple completed and dedicated in 516 BCE. Around 19 BCE Herod the Great began a massive expansion project on the Temple Mount. In addition to fully rebuilding and enlarging the Temple, he artificially expanded the platform on which it stood, doubling it in size. Today's Western Wall formed part of the retaining perimeter wall of this platform. In 2011, Israeli archaeologists announced the surprising discovery of Roman coins minted well after Herod's death, found under the foundation stones of the wall. The excavators came upon the coins inside a ritual bath that predates Herod's building project, which was filled in to create an even base for the wall and was located under its southern section.[2] This seems to indicate that Herod did not finish building the entire wall by the time of his death in 4 BCE. The find confirms the description by historian Josephus Flavius, which states that construction was finished only during the reign of King Agrippa II, Herod's great-grandson.[3] Given Josephus' information, the surprise mainly regarded the fact that an unfinished retaining wall in this area could also mean that at least parts of the splendid Royal Stoa and the monumental staircase leading up to it could not have been completed during Herod's lifetime. Also surprising was the fact that the usually very thorough Herodian builders had cut corners by filling in the ritual bath, rather than placing the foundation course directly onto the much firmer bedrock. Some scholars are doubtful of the interpretation and have offered alternative explanations, such as, for example, later repair work.

Herod's Temple was destroyed by the Romans, along with the rest of Jerusalem, in 70 CE,[4] during the First Jewish–Roman War.

Late Roman and Byzantine periods (135–638)During much of the 2nd–5th centuries of the Common Era, after the Roman defeat of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, Jews were banned from Jerusalem. There is some evidence that Roman emperors in the 2nd and 3rd centuries did permit them to visit the city to worship on the Mount of Olives and sometimes on the Temple Mount itself.[5] When the empire started becoming Christian under Constantine I, they were given permission to enter the city once a year, on the Tisha B'Av, to lament the loss of the Temple at the wall.[6] The Bordeaux Pilgrim, who wrote in 333 CE, suggests that it was probably to the perforated stone or the Rock of Moriah, "to which the Jews come every year and anoint it, bewail themselves with groans, rend their garments, and so depart".This was because an imperial decree from Rome barred Jews from living in Jerusalem. Just once per year they were permitted to return and bitterly grieve about the fate of their people. Comparable accounts survive, including those by the Church Father, Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390) and by Jerome in his commentary to Zephaniah written in 392 CE. In the 4th century, Christian sources reveal that the Jews encountered great difficulty in buying the right to pray near the Western Wall, at least on the 9th of Av.[5] In 425 CE, the Jews of the Galilee wrote to Byzantine empress Aelia Eudocia seeking permission to pray by the ruins of the Temple. Permission was granted and they were officially permitted to resettle in Jerusalem.[7]

ArchaeologyDiscovery of underground rooms that could have been used as food storage carved out of the bedrock under the 1,400-year-old mosaic floor of Byzantine structure was announced by Israel Antiquities Authority in May in 2020.

"At first we were very disappointed because we found we hit the bedrock, meaning that the material culture, the human activity here in Jerusalem ended. What we found here was a rock-cut system—three rooms, all hewn in the bedrock of ancient Jerusalem" said co-director of the excavation Barak Monnickendam-Givon.[8]

Early Muslim to Mamluk period (638–1517)Several Jewish authors of the 10th and 11th centuries write about the Jews resorting to the Western Wall for devotional purposes.[9][10] Ahimaaz relates that Rabbi Samuel ben Paltiel (980–1010) gave money for oil at "the sanctuary at the Western Wall."[11][12][13] Benjamin of Tudela (1170) wrote "In front of this place is the Western Wall, which is one of the walls of the Holy of Holies. This is called the Gate of Mercy, and hither come all the Jews to pray before the Wall in the open court." The account gave rise to confusion about the actual location of Jewish worship, and some suggest that Benjamin in fact referred to the Eastern Wall along with its Gate of Mercy.[14][15] While Nahmanides (d. 1270) did not mention a synagogue near the Western Wall in his detailed account of the temple site,[16] shortly before the Crusader period a synagogue existed at the site.[17] Obadiah of Bertinoro (1488) states "the Western Wall, part of which is still standing, is made of great, thick stones, larger than any I have seen in buildings of antiquity in Rome or in other lands."[18]

Shortly after Saladin's 1187 siege of the city, in 1193, the sultan's son and successor al-Afdal established the land adjacent to the wall as a charitable trust (waqf). The largest part of it was named after an important mystic, Abu Madyan Shu'aib. The Abu Madyan waqf was dedicated to Maghrebian pilgrims and scholars who had taken up residence there, and houses were built only metres away from the wall, from which they were thus separated by just a narrow passageway,[19] some 4 metres (13 ft) wide.[citation needed]

The first likely mention of the Islamic tradition that Buraq was tethered at the site is from the 14th century. A manuscript by Ibrahim b. Ishaq al-Ansari (known as Ibn Furkah, d. 1328) refers to Bab al-Nabi (lit. "Gate of the Prophet"), an old name for Barclay's Gate below the Maghrebi Gate.[20][21] Charles D. Matthews however, who editted al-Firkah's work, notes that other statements of al-Firkah might seem to point to the Double Gate in the southern wall.[22]

Ottoman period (1517–1917) Wailing Wall, Jerusalem by Gustav Bauernfeind (19th century)

Wailing Wall, Jerusalem by Gustav Bauernfeind (19th century)In 1517, the Turkish Ottomans under Selim I conquered Jerusalem from the Mamluks who had held it since 1250. Selim's son, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, ordered the construction of an imposing wall to be built around the entire city, which still stands today. Various folktales relate Suleiman's quest to locate the Temple site and his order to have the area "swept and sprinkled, and the Western Wall washed with rosewater" upon its discovery.[23] According to a legend cited by Moses Hagiz, Jews received official permission to worship at the site and Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan built an oratory for them there,[24] but, as of Purim 1625, Jews were banned from praying on the Temple Mount and only sometimes dared to pray at the Western Wall, for which purpose a special liturgy had been arranged.[25]

Over the centuries, land close to the Wall became built up. Public access to the Wall was through the Moroccan Quarter, a labyrinth of narrow alleyways. In May 1840 a firman issued by Ibrahim Pasha forbade the Jews to pave the passageway in front of the Wall. It also cautioned them against "raising their voices and displaying their books there." They were, however, allowed "to pay visits to it as of old."[10]

Rabbi Joseph Schwarz writing in the mid-19th century records:

This wall is visited by all our brothers on every feast and festival; and the large space at its foot is often so densely filled up, that all cannot perform their devotions here at the same time. It is also visited, though by less numbers, on every Friday afternoon, and by some nearly every day. No one is molested in these visits by the Mahomedans, as we have a very old firman from the Sultan of Constantinople that the approach shall not be denied to us, though the Porte obtains for this privilege a special tax, which is, however, quite insignificant.[26]

Over time the increased numbers of people gathering at the site resulted in tensions between the Jewish visitors who wanted easier access and more space, and the residents, who complained of the noise.[10] This gave rise to Jewish attempts at gaining ownership of the land adjacent to the Wall.

The Western Wall in c. 1870, squeezed in by houses of the Moroccan Quarter, a century before they were demolished

The Western Wall in c. 1870, squeezed in by houses of the Moroccan Quarter, a century before they were demolishedIn the late 1830s a wealthy Jew named Shemarya Luria attempted to purchase houses near the Wall, but was unsuccessful,[27] as was Jewish sage Abdullah of Bombay who tried to purchase the Western Wall in the 1850s.[28] In 1869 Rabbi Hillel Moshe Gelbstein settled in Jerusalem. He arranged that benches and tables be brought to the Wall on a daily basis for the study groups he organised and the minyan which he led there for years. He also formulated a plan whereby some of the courtyards facing the Wall would be acquired, with the intention of establishing three synagogues—one each for the Sephardim, the Hasidim and the Perushim.[29] He also endeavoured to re-establish an ancient practice of "guards of honour", which according to the mishnah in Middot, were positioned around the Temple Mount. He rented a house near the Wall and paid men to stand guard there and at various other gateways around the mount. However, this set-up lasted only for a short time due to lack of funds or because of Arab resentment.[30] In 1874, Mordechai Rosanes paid for the repaving of the alleyway adjacent to the wall.[31]

In 1887 Baron Rothschild conceived a plan to purchase and demolish the Moroccan Quarter as "a merit and honor to the Jewish People."[32] The proposed purchase was considered and approved by the Ottoman Governor of Jerusalem, Rauf Pasha, and by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Tahir Husseini. Even after permission was obtained from the highest secular and Muslim religious authority to proceed, the transaction was shelved after the authorities insisted that after demolishing the quarter no construction of any type could take place there, only trees could be planted to beautify the area. Additionally the Jews would not have full control over the area. This meant that they would have no power to stop people from using the plaza for various activities, including the driving of mules, which would cause a disturbance to worshippers.[32] Other reports place the scheme's failure on Jewish infighting as to whether the plan would foster a detrimental Arab reaction.[33]

Jews' Wailing Place, Jerusalem, 1891

Jews' Wailing Place, Jerusalem, 1891In 1895 Hebrew linguist and publisher Rabbi Chaim Hirschensohn became entangled in a failed effort to purchase the Western Wall and lost all his assets.[34] The attempts of the Palestine Land Development Company to purchase the environs of the Western Wall for the Jews just before the outbreak of World War I also never came to fruition.[28] In the first two months following the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War, the Turkish governor of Jerusalem, Zakey Bey, offered to sell the Moroccan Quarter, which consisted of about 25 houses, to the Jews in order to enlarge the area available to them for prayer. He requested a sum of £20,000 which would be used to both rehouse the Muslim families and to create a public garden in front of the Wall. However, the Jews of the city lacked the necessary funds. A few months later, under Muslim Arab pressure on the Turkish authorities in Jerusalem, Jews became forbidden by official decree to place benches and light candles at the Wall. This sour turn in relations was taken up by the Chacham Bashi who managed to get the ban overturned.[35] In 1915 it was reported that Djemal Pasha, closed off the wall to visitation as a sanitary measure.[36] Probably meant was the "Great", rather than the "Small" Djemal Pasha.

Decrees (firman)s issued regarding the Wall:

Year Issued by Content c. 1560 Suleiman the Magnificent Official recognition of the right of Jews to pray by the Wall[37][38]1840 Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt Forbidding the Jews to pave the passage in front of the Wall. It also cautioned them against "raising their voices and displaying their books there." They were, however, allowed "to pay visits to it as of old."[10]1841* Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt "Of the same bearing and likewise to two others of 1893 and 1909"[10]1889* Abdul Hamid II That there shall be no interference with the Jews' places of devotional visits and of pilgrimage, that are situated in the localities which are dependent on the Chief Rabbinate, nor with the practice of their ritual.[10]1893* Confirming firman of 1889[10]1909* Confirming firman of 1889[10]1911 Administrative Council of the Liwa Prohibiting the Jews from certain appurtenances at the Wall[10]These firmans were cited by the Jewish contingent at the International Commission, 1930, as proof for rights at the Wall. Muslim authorities responded by arguing that historic sanctions of Jewish presence were acts of tolerance shown by Muslims, who, by doing so, did not concede any positive rights.[39]British rule (1917–48) Jewish Legion soldiers at the Western Wall after British conquest of Jerusalem, 1917

Jewish Legion soldiers at the Western Wall after British conquest of Jerusalem, 1917 1920. From the collection of the National Library of Israel

1920. From the collection of the National Library of IsraelIn December 1917, Allied forces under Edmund Allenby captured Jerusalem from the Turks. Allenby pledged "that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred".[40]

In 1919 Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann approached the British Military Governor of Jerusalem, Colonel Sir Ronald Storrs, and offered between £75,000[41] and £100,000[42] (approx. £5m in modern terms) to purchase the area at the foot of the Wall and rehouse the occupants. Storrs was enthusiastic about the idea because he hoped some of the money would be used to improve Muslim education. Although they appeared promising at first, negotiations broke down after strong Muslim opposition.[42][43] Storrs wrote two decades later:

The acceptance of the proposals, had it been practicable, would have obviated years of wretched humiliations, including the befouling of the Wall and pavement and the unmannerly braying of the tragi-comic Arab band during Jewish prayer, and culminating in the horrible outrages of 1929.[41]

In early 1920, the first Jewish-Arab dispute over the Wall occurred when the Muslim authorities were carrying out minor repair works to the Wall's upper courses. The Jews, while agreeing that the works were necessary, appealed to the British that they be made under supervision of the newly formed Department of Antiquities, because the Wall was an ancient relic.[44]

According to Hillel Halkin, in the 1920s, among rising tensions with the Jews regarding the wall, the Arabs ceased using the more traditional name El-Mabka, "the Place of Weeping", which related to Jewish practices, and replaced it with El-Burak, a name with Muslim connotations.[45]

In 1926 an effort was made to lease the Maghrebi waqf, which included the wall, with the plan of eventually buying it.[46] Negotiations were begun in secret by the Jewish judge Gad Frumkin, with financial backing from American millionaire Nathan Straus.[46] The chairman of the Palestine Zionist Executive, Colonel F. H. Kisch, explained that the aim was "quietly to evacuate the Moroccan occupants of those houses which it would later be necessary to demolish" to create an open space with seats for aged worshippers to sit on.[46] However, Straus withdrew when the price became excessive and the plan came to nothing.[47] The Va'ad Leumi, against the advice of the Palestine Zionist Executive, demanded that the British expropriate the wall and give it to the Jews, but the British refused.[46]

In 1928 the World Zionist Organization reported that John Chancellor, High Commissioner of Palestine, believed that the Western Wall should come under Jewish control and wondered "why no great Jewish philanthropist had not bought it yet".[48]

September 1928 disturbancesIn 1922, a Status Quo agreement issued by the mandatory authority forbade the placing of benches or chairs near the Wall. The last occurrence of such a ban was in 1915, but the Ottoman decree was soon retracted after intervention of the Chacham Bashi. In 1928 the District Commissioner of Jerusalem, Edward Keith-Roach, acceded to an Arab request to implement the ban. This led to a British officer being stationed at the Wall making sure that Jews were prevented from sitting. Nor were Jews permitted to separate the sexes with a screen. In practice, a flexible modus vivendi had emerged and such screens had been put up from time to time when large numbers of people gathered to pray.

The placing of a Mechitza similar to the one in the picture was the catalyst for confrontation between the Arabs, Jews and Mandate authorities in 1928.

The placing of a Mechitza similar to the one in the picture was the catalyst for confrontation between the Arabs, Jews and Mandate authorities in 1928.On September 24, 1928, the Day of Atonement, British police resorted to removing by force a screen used to separate men and women at prayer. Women who tried to prevent the screen being dismantled were beaten by the police, who used pieces of the broken wooden frame as clubs. Chairs were then pulled out from under elderly worshipers. The episode made international news and Jews the world over objected to the British action. Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the Chief Rabbi of the ultraorthodox Jews in Jerusalem, issued a protest letter on behalf of his community, the Edah HaChareidis, and Agudas Yisroel strongly condemning the desecration of the holy site. Various communal leaders called for a general strike. A large rally was held in the Etz Chaim Yeshiva, following which an angry crowd attacked the local police station in which they believed Douglas Valder Duff, the British officer involved, was sheltering.[49]

Commissioner Edward Keith-Roach described the screen as violating the Ottoman status quo that forbade Jews from making any construction in the Western Wall area. He informed the Jewish community that the removal had been carried out under his orders after receiving a complaint from the Supreme Muslim Council. The Arabs were concerned that the Jews were trying to extend their rights at the wall and with this move, ultimately intended to take possession of the Masjid Al-Aqsa.[50] The British government issued an announcement explaining the incident and blaming the Jewish beadle at the Wall. It stressed that the removal of the screen was necessary, but expressed regret over the ensuing events.[49]

A widespread Arab campaign to protest against presumed Jewish intentions and designs to take possession of the Al Aqsa Mosque swept the country and a "Society for the Protection of the Muslim Holy Places" was established.[51] The Jewish National Council (Vaad Leumi) responding to these Arab fears declared in a statement that "We herewith declare emphatically and sincerely that no Jew has ever thought of encroaching upon the rights of Moslems over their own Holy places, but our Arab brethren should also recognise the rights of Jews in regard to the places in Palestine which are holy to them."[50] The committee also demanded that the British administration expropriate the wall for the Jews.[52]

From October 1928 onward, Mufti Amin al-Husayni organised a series of measures to demonstrate the Arabs' exclusive claims to the Temple Mount and its environs. He ordered new construction next to and above the Western Wall.[53] The British granted the Arabs permission to convert a building adjoining the Wall into a mosque and to add a minaret. A muezzin was appointed to perform the Islamic call to prayer and Sufi rites directly next to the Wall. These were seen as a provocation by the Jews who prayed at the Wall.[54][55] The Jews protested and tensions increased.

British police post at the entrance to the Western Wall, 1933

British police post at the entrance to the Western Wall, 1933 British police at the Wailing Wall, 1934

British police at the Wailing Wall, 1934A British inquiry into the disturbances and investigation regarding the principal issue in the Western Wall dispute, namely the rights of the Jewish worshipers to bring appurtenances to the wall, was convened. The Supreme Muslim Council provided documents dating from the Turkish regime supporting their claims. However, repeated reminders to the Chief Rabbinate to verify which apparatus had been permitted failed to elicit any response. They refused to do so, arguing that Jews had the right to pray at the Wall without restrictions.[56] Subsequently, in November 1928, the Government issued a White Paper entitled "The Western or Wailing Wall in Jerusalem: Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies", which emphasised the maintenance of the status quo and instructed that Jews could only bring "those accessories which had been permitted in Turkish times."[57]

A few months later, Haj Amin complained to Chancellor that "Jews were bringing benches and tables in increased numbers to the wall and driving nails into the wall and hanging lamps on them."[58]

1929 Palestine riotsIn the summer of 1929, the Mufti Haj Amin Al Husseinni ordered an opening be made at the southern end of the alleyway which straddled the Wall. The former cul-de-sac became a thoroughfare which led from the Temple Mount into the prayer area at the Wall. Mules were herded through the narrow alley, often dropping excrement. This, together with other construction projects in the vicinity, and restricted access to the Wall, resulted in Jewish protests to the British, who remained indifferent.[56]

On August 14, 1929, after attacks on individual Jews praying at the Wall, 6,000 Jews demonstrated in Tel Aviv, shouting "The Wall is ours." The next day, the Jewish fast of Tisha B'Av, 300 youths raised the Zionist flag and sang Hatikva at the Wall.[52] The day after, on August 16, an organized mob of 2,000 Muslim Arabs descended on the Western Wall, injuring the beadle and burning prayer books, liturgical fixtures and notes of supplication. The rioting spread to the Jewish commercial area of town, and was followed a few days later by the Hebron massacre.[59] One hundred and thirty-three Jews were killed and 339 injured in the Arab riots, and in the subsequent process of quelling the riots 110 Arabs were killed by British police. This was by far the deadliest attack on Jews during the period of British Rule over Palestine.

1930 international commissionIn 1930, in response to the 1929 riots, the British Government appointed a commission "to determine the rights and claims of Muslims and Jews in connection with the Western or Wailing Wall", and to determine the causes of the violence and prevent it in the future. The League of Nations approved the commission on condition that the members were not British.

The Commission noted that "the Jews do not claim any proprietorship to the Wall or to the Pavement in front of it (concluding speech of Jewish Counsel, Minutes, page 908)."

Members of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry at the Western Wall, 1946

Members of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry at the Western Wall, 1946The Commission concluded that the wall, and the adjacent pavement and Moroccan Quarter, were solely owned by the Muslim waqf. However, Jews had the right to "free access to the Western Wall for the purpose of devotions at all times", subject to some stipulations that limited which objects could be brought to the Wall and forbade the blowing of the shofar, which was made illegal. Muslims were forbidden to disrupt Jewish devotions by driving animals or other means.[10]

The recommendations of the Commission were brought into law by the Palestine (Western or Wailing Wall) Order in Council, 1931, which came into effect on June 8, 1931.[60] Persons violating the law were liable to a fine of 50 pounds or imprisonment up to 6 months, or both.[60]

During the 1930s, at the conclusion of Yom Kippur, young Jews persistently flouted the shofar ban each year and blew the shofar resulting in their arrest and prosecution. They were usually fined or sentenced to imprisonment for three to six months. The Shaw commission determined that the violence occurred due to "racial animosity on the part of the Arabs, consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future."

Jordanian rule (1948–67)During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War the Old City together with the Wall was controlled by Jordan. Article VIII of the 1949 Armistice Agreement called for a Special Committee to make arrangements for (amongst other things) "free access to the Holy Places and cultural institutions and use of the cemetery on the Mount of Olives".[61] The committee sat multiple times during 1949, but both sides made additional demands and at the same time the Palestine Conciliation Commission was pressing for the internationalization of Jerusalem against the wishes of both parties.[62] No agreement was ever reached, leading to recriminations in both directions. Neither Israeli Arabs nor Israeli Jews could visit their holy places in the Jordanian territories.[63][64] An exception was made for Christians to participate in Christmas ceremonies in Bethlehem.[64] Some sources claim Jews could only visit the wall if they traveled through Jordan (which was not an option for Israelis) and did not have an Israeli visa stamped in their passports.[65] Only Jordanian soldiers and tourists were to be found there. A vantage point on Mount Zion, from which the Wall could be viewed, became the place where Jews gathered to pray. For thousands of pilgrims, the mount, being the closest location to the Wall under Israeli control, became a substitute site for the traditional priestly blessing ceremony which takes place on the Three Pilgrimage Festivals.[66]

"Al Buraq (Wailing Wall) Rd" signDuring the Jordanian rule of the Old City, a ceramic street sign in Arabic and English was affixed to the stones of the ancient wall. Attached 2.1 metres (6.9 ft) up, it was made up of eight separate ceramic tiles and said Al Buraq Road in Arabic at the top with the English "Al-Buraq (Wailing Wall) Rd" below. When Israeli soldiers arrived at the wall in June 1967, one attempted to scrawl Hebrew lettering on it.[67] The Jerusalem Post reported that on June 8, Ben-Gurion went to the wall and "looked with distaste" at the road sign; "this is not right, it should come down" and he proceeded to dismantle it.[68] This act signaled the climax of the capture of the Old City and the ability of Jews to once again access their holiest sites.[69] Emotional recollections of this event are related by David Ben-Gurion and Shimon Peres.[70]

First years under Israeli rule (1967–69) Declarations after the conquest The iconic image of Israeli soldiers shortly after the capture of the Wall during the Six-Day War

The iconic image of Israeli soldiers shortly after the capture of the Wall during the Six-Day WarFollowing Israel's victory during the 1967 Six-Day War, the Western Wall came under Israeli control. Brigadier Rabbi Shlomo Goren proclaimed after its capture that "Israel would never again relinquish the Wall", a stance supported by Israeli Minister for Defence Moshe Dayan and Chief of Staff General Yitzhak Rabin.[71] Rabin described the moment Israeli soldiers reached the Wall:

"There was one moment in the Six-Day War which symbolized the great victory: that was the moment in which the first paratroopers—under Gur's command—reached the stones of the Western Wall, feeling the emotion of the place; there never was, and never will be, another moment like it. Nobody staged that moment. Nobody planned it in advance. Nobody prepared it and nobody was prepared for it; it was as if Providence had directed the whole thing: the paratroopers weeping—loudly and in pain—over their comrades who had fallen along the way, the words of the Kaddish prayer heard by Western Wall's stones after 19 years of silence, tears of mourning, shouts of joy, and the singing of "Hatikvah"".[72]

Demolition of the Moroccan Quarter Moroccan Quarter (cell J9) surrounding the Western Wall (numbered 62) in the 1947 Survey of Palestine map. The two mosques demolished after 1967 are shown in red.

Moroccan Quarter (cell J9) surrounding the Western Wall (numbered 62) in the 1947 Survey of Palestine map. The two mosques demolished after 1967 are shown in red.Forty-eight hours after capturing the wall, the military, without explicit government order,[73] hastily proceeded to demolish the entire Moroccan Quarter, which stood 4 metres (13 ft) from the Wall.[74] The Sheikh Eid Mosque, which was built over one of Jerusalem's oldest Islamic schools, the Afdiliyeh, named after one of Saladin's sons, was pulled down to make way for the plaza. It was one of three or four that survived from Saladin's time.[75] 106 Arab families consisting of 650 people were ordered to leave their homes at night. When they refused, bulldozers began to demolish the buildings with people still inside, killing one person and injuring a number of others.[76][77][78][79]

According to Eyal Weizman, Chaim Herzog, who later became Israel's sixth president, took much of the credit for the destruction of the neighbourhood:

When we visited the Wailing Wall we found a toilet attached to it ... we decided to remove it and from this we came to the conclusion that we could evacuate the entire area in front of the Wailing Wall ... a historical opportunity that will never return ... We knew that the following Saturday [sic Wednesday], June 14, would be the Jewish festival of Shavuot and that many will want to come to pray ... it all had to be completed by then.[80]

Historian Matthew Teller, who investigated the story of the toilet, judged it as improbable.[81]

The narrow pavement, which could accommodate a maximum of 12,000 per day, was transformed into an enormous plaza that could hold in excess of 400,000.[82] Several months later, the pavement close to the wall was excavated to a depth of two and half metres, exposing an additional two courses of large stones.[83]

A complex of buildings against the wall at the southern end of the plaza, that included Madrasa Fakhriya and the house that the Abu al-Sa'ud family had occupied since the 16th century, were spared in the 1967 destruction, but demolished in 1969.[84][85] The section of the wall dedicated to prayers was thus extended southwards to double its original length, from 28 to 60 metres (92 to 197 ft), while the 4 metres (13 ft) space facing the wall grew to 40 metres (130 ft).

The narrow, approximately 120 square metres (1,300 sq ft) pre-1948 alley along the wall, used for Jewish prayer, was enlarged to 2,400 square metres (26,000 sq ft), with the entire Western Wall Plaza covering 20,000 square metres (4.9 acres), stretching from the wall to the Jewish Quarter.[86]

Add new comment