Jerusalem (; Hebrew: יְרוּשָׁלַיִם Yerushaláyim, pronounced [jeʁuʃaˈlajim] ; Arabic: القُدس al-Quds, pronounced [al.quds] , local pronunciation: [il.ʔuds]) is an ancient city in West Asia, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the oldest cities in the world, and is considered holy to the three major Abrahamic religions—Judais...Read more

Jerusalem (; Hebrew: יְרוּשָׁלַיִם Yerushaláyim, pronounced [jeʁuʃaˈlajim] ; Arabic: القُدس al-Quds, pronounced [al.quds] , local pronunciation: [il.ʔuds]) is an ancient city in West Asia, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the oldest cities in the world, and is considered holy to the three major Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Both the State of Israel and Palestine claim Jerusalem as their capital; Israel maintains its primary governmental institutions there, and Palestine ultimately foresees it as its seat of power. Neither claim, however, is widely recognized internationally.

Throughout its long history, Jerusalem has been destroyed at least twice, besieged 23 times, captured and recaptured 44 times, and attacked 52 times. The part of Jerusalem called the City of David shows first signs of settlement in the 4th millennium BCE, in the shape of encampments of nomadic shepherds. During the Canaanite period (14th century BCE), Jerusalem was named as Urusalim on ancient Egyptian tablets, probably meaning "City of Shalem" after a Canaanite deity. During the Israelite period, significant construction activity in Jerusalem began in the 10th century BCE (Iron Age II), and by the 9th century BCE, the city had developed into the religious and administrative centre of the Kingdom of Judah. In 1538, the city walls were rebuilt for a last time around Jerusalem under Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire. Today those walls define the Old City, which since the 19th century has been divided into four quarters – the Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim quarters. The Old City became a World Heritage Site in 1981, and is on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Since 1860, Jerusalem has grown far beyond the Old City's boundaries. In 2022, Jerusalem had a population of some 971,800 residents, of which almost 60% were Jews and almost 40% Palestinians. In 2020, the population was 951,100, of which Jews comprised 570,100 (59.9%), Muslims 353,800 (37.2%), Christians 16,300 (1.7%), and 10,800 unclassified (1.1%).

According to the Hebrew Bible, King David conquered the city from the Jebusites and established it as the capital of the United Kingdom of Israel, and his son, King Solomon, commissioned the building of the First Temple. Modern scholars argue that Jews branched out of the Canaanite peoples and culture through the development of a distinct monolatrous—and later monotheistic—religion centred on El/Yahweh. These foundational events, straddling the dawn of the 1st millennium BCE, assumed central symbolic importance for the Jewish people. The sobriquet of holy city (Hebrew: עיר הקודש, romanized: 'Ir ha-Qodesh) was probably attached to Jerusalem in post-exilic times. The holiness of Jerusalem in Christianity, conserved in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, which Christians adopted as the Old Testament, was reinforced by the New Testament account of Jesus's crucifixion and resurrection there. Meanwhile in Sunni Islam, Jerusalem is the third-holiest city, after Mecca and Medina. The city was the first standard direction for Muslim prayers, and in Islamic tradition, Muhammad made his Night Journey there in 621, ascending to heaven where he speaks to God, per the Quran. As a result, despite having an area of only 0.9 km2 (3⁄8 sq mi), the Old City is home to many sites of seminal religious importance, among them the Temple Mount with its Western Wall, Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

At present, the status of Jerusalem remains one of the core issues in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, West Jerusalem was among the areas incorporated into Israel, while East Jerusalem, including the Old City, was occupied and annexed by Jordan. Israel occupied East Jerusalem from Jordan during the 1967 Six-Day War and subsequently annexed it into the city's municipality, together with additional surrounding territory. One of Israel's Basic Laws, the 1980 Jerusalem Law, refers to Jerusalem as the country's undivided capital. All branches of the Israeli government are located in Jerusalem, including the Knesset (Israel's parliament), the residences of the Prime Minister and President, and the Supreme Court. The international community rejects the annexation as illegal and regards East Jerusalem as Palestinian territory occupied by Israel.

Given the city's central position in both Jewish nationalism (Zionism) and Palestinian nationalism, the selectivity required to summarize some 5,000 years of inhabited history is often influenced by ideological bias or background.[1] Israeli or Jewish nationalists claim a right to the city based on Jewish indigeneity to the land, particularly their origins in and descent from the Israelites, for whom Jerusalem is their capital, and their yearning for return.[2][3] In contrast, Palestinian nationalists claim the right to the city based on modern Palestinians' longstanding presence and descent from many different peoples who have settled or lived in the region over the centuries. Another reason for their claim, which is also supported by the Arab and Muslim world, is significance of Jerusalem in Islam.[4][5] Both sides claim the history of the city has been politicized by the other in order to strengthen their relative claims to the city,[6][7][8] and that this is borne out by the different focuses the different writers place on the various events and eras in the city's history.

Overview of Jerusalem's historical periods (by rulers)

The first archaeological evidence of human presence in the area comes in the form of flints dated to between 6000 and 7000 years ago,[9] with ceramic remains appearing during the Chalcolithic period, and the first signs of permanent settlement appearing in the Early Bronze Age in 3000–2800 BCE.[10][11]

Bronze and Iron Ages Stepped Stone Structure from the Bronze Age and Iron Age on the southeastern slope of old Jerusalem

Stepped Stone Structure from the Bronze Age and Iron Age on the southeastern slope of old JerusalemThe earliest evidence of city fortifications appear in the Mid to Late Bronze Age and could date to around the 18th century BCE.[12] By around 1550–1200 BCE, Jerusalem was the capital of an Egyptian vassal city-state,[13] a modest settlement governing a few outlying villages and pastoral areas, with a small Egyptian garrison and ruled by appointees such as king Abdi-Heba.[14] At the time of Seti I (r. 1290–1279 BCE) and Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BCE), major construction took place as prosperity increased.[15] The city's inhabitants at this time were Canaanites, who are believed by scholars to have evolved into the Israelites via the development of a distinct Yahweh-centric monotheistic belief system.[16][17][18]

The Siloam Inscription, written in Biblical Hebrew, commemorates the construction of the Siloam tunnel (c. 700 BCE)

The Siloam Inscription, written in Biblical Hebrew, commemorates the construction of the Siloam tunnel (c. 700 BCE)Archaeological remains from the ancient Israelite period include the Siloam Tunnel, an aqueduct built by Judahite king Hezekiah and once containing an ancient Hebrew inscription, known as the Siloam Inscription;[19] the so-called Broad Wall, a defensive fortification built in the 8th century BCE, also by Hezekiah;[20] the Silwan necropolis (9th–7th c. BCE) with the Monolith of Silwan and the Tomb of the Royal Steward, which were decorated with monumental Hebrew inscriptions;[21] and the so-called Israelite Tower, remnants of ancient fortifications, built from large, sturdy rocks with carved cornerstones.[22] A huge water reservoir dating from this period was discovered in 2012 near Robinson's Arch, indicating the existence of a densely built-up quarter across the area west of the Temple Mount during the Kingdom of Judah.[23]

When the Assyrians conquered the Kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE, Jerusalem was strengthened by a great influx of refugees from the northern kingdom. When Hezekiah ruled, Jerusalem had no fewer than 25,000 inhabitants and covered 25 acres (10 hectares).[24]

In 587–586 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire conquered Jerusalem after a prolonged siege, and then systematically destroyed the city, including Solomon's Temple.[25] The Kingdom of Judah was abolished and many were exiled to Babylon. These events mark the end of the First Temple period.[26]

Biblical accountThis period, when Canaan formed part of the Egyptian empire, corresponds in biblical accounts to Joshua's invasion,[27] but almost all scholars agree that the Book of Joshua holds little historical value for early Israel.[28]

Modern-day reconstruction of Jerusalem during the reign of Solomon (10th century BCE). Solomon's Temple appears on top.

Modern-day reconstruction of Jerusalem during the reign of Solomon (10th century BCE). Solomon's Temple appears on top.In the Bible, Jerusalem is defined as lying within territory allocated to the tribe of Benjamin[29] though still inhabited by Jebusites. David is said to have conquered these in the siege of Jebus, and transferred his capital from Hebron to Jerusalem which then became the capital of a United Kingdom of Israel,[30] and one of its several religious centres.[31] The choice was perhaps dictated by the fact that Jerusalem did not form part of Israel's tribal system, and was thus suited to serve as the centre of its confederation.[15] Opinion is divided over whether the so-called Large Stone Structure and the nearby Stepped Stone Structure may be identified with King David's palace, or dates to a later period.[32][33]

According to the Bible, King David reigned for 40 years[34] and was succeeded by his son Solomon,[35] who built the Holy Temple on Mount Moriah. Solomon's Temple (later known as the First Temple), went on to play a pivotal role in Jewish religion as the repository of the Ark of the Covenant.[36] On Solomon's death, ten of the northern tribes of Israel broke with the United Monarchy to form their own nation, with its kings, prophets, priests, traditions relating to religion, capitals and temples in northern Israel. The southern tribes, together with the Aaronid priesthood, remained in Jerusalem, with the city becoming the capital of the Kingdom of Judah.[37][38]

Classical antiquity Second Temple periodIn 538 BCE, the Achaemenid King Cyrus the Great invited the Jews of Babylon to return to Judah to rebuild the Temple.[39][40] Construction of the Second Temple was completed in 516 BCE, during the reign of Darius the Great, 70 years after the destruction of the First Temple.[41][42]

Sometime soon after 485 BCE Jerusalem was besieged, conquered and largely destroyed by a coalition of neighbouring states.[43] In about 445 BCE, King Artaxerxes I of Persia issued a decree allowing the city (including its walls) to be rebuilt.[44][better source needed] Jerusalem resumed its role as capital of Judah and centre of Jewish worship.

Holyland Model of Jerusalem, depicting the city during the late Second Temple period. First created in 1966, it is continuously updated according to advancing archaeological knowledge.

Holyland Model of Jerusalem, depicting the city during the late Second Temple period. First created in 1966, it is continuously updated according to advancing archaeological knowledge.Many Jewish tombs from the Second Temple period have been unearthed in Jerusalem. One example, discovered north of the Old City, contains human remains in a 1st-century CE ossuary decorated with the Aramaic inscription "Simon the Temple Builder".[45] The Tomb of Abba, also located north of the Old City, bears an Aramaic inscription with Paleo-Hebrew letters reading: "I, Abba, son of the priest Eleaz(ar), son of Aaron the high (priest), Abba, the oppressed and the persecuted, who was born in Jerusalem, and went into exile into Babylonia and brought (back to Jerusalem) Mattathi(ah), son of Jud(ah), and buried him in a cave which I bought by deed."[46] The Tomb of Benei Hezir located in Kidron Valley is decorated by monumental Doric columns and Hebrew inscription, identifying it as the burial site of Second Temple priests. The Tombs of the Sanhedrin, an underground complex of 63 rock-cut tombs, is located in a public park in the northern Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sanhedria. These tombs, probably reserved for members of the Sanhedrin[47][48] and inscribed by ancient Hebrew and Aramaic writings, are dated to between 100 BCE and 100 CE.

When Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire, Jerusalem and Judea came under Macedonian control, eventually falling to the Ptolemaic dynasty under Ptolemy I. In 198 BCE, Ptolemy V Epiphanes lost Jerusalem and Judea to the Seleucids under Antiochus III. The Seleucid attempt to recast Jerusalem as a Hellenized city-state came to a head in 168 BCE with the successful Maccabean revolt of Mattathias and his five sons against Antiochus IV Epiphanes, and their establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom in 152 BCE with Jerusalem as its capital.

A coin issued by the Jewish rebels in 68 CE. Obverse: "Shekel, Israel. Year 3". Reverse: "Jerusalem the Holy", in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

A coin issued by the Jewish rebels in 68 CE. Obverse: "Shekel, Israel. Year 3". Reverse: "Jerusalem the Holy", in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans (David Roberts, 1850)

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans (David Roberts, 1850)In 63 BCE, Pompey the Great intervened in a struggle for the Hasmonean throne and captured Jerusalem, extending the influence of the Roman Republic over Judea.[49] Following a short invasion by Parthians, backing the rival Hasmonean rulers, Judea became a scene of struggle between pro-Roman and pro-Parthian forces, eventually leading to the emergence of an Edomite named Herod. As Rome became stronger, it installed Herod as a client king of the Jews. Herod the Great, as he was known, devoted himself to developing and beautifying the city. He built walls, towers and palaces, and expanded the Temple Mount, buttressing the courtyard with blocks of stone weighing up to 100 tons. Under Herod, the area of the Temple Mount doubled in size.[35][50][51] Shortly after Herod's death, in 6 CE Judea came under direct Roman rule as the Iudaea Province,[52] although the Herodian dynasty through Agrippa II remained client kings of neighbouring territories until 96 CE.

Roman rule over Jerusalem and Judea was challenged in the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), which ended with a Roman victory. Early on, the city was devastated by a brutal civil war between several Jewish factions fighting for control of the city. In 70 CE, the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the Second Temple.[53][54][55][56][57] The contemporary Jewish historian Josephus wrote that the city "was so thoroughly razed to the ground by those that demolished it to its foundations, that nothing was left that could ever persuade visitors that it had once been a place of habitation."[58] Of the 600,000 (Tacitus) or 1,000,000 (Josephus) Jews of Jerusalem, all of them either died of starvation, were killed or were sold into slavery.[59] Roman rule was again challenged during the Bar Kokhba revolt, beginning in 132 CE and suppressed by the Romans in 135 CE. More recent research indicates that the Romans had founded Aelia Capitolina before the outbreak of the revolt, and found no evidence for Bar Kokhba ever managing to hold the city.[60]

Jerusalem reached a peak in size and population at the end of the Second Temple Period, when the city covered two km2 (3⁄4 sq mi) and had a population of 200,000.[61][50]

Late AntiquityFollowing the Bar Kokhba revolt, Emperor Hadrian combined Iudaea Province with neighbouring provinces under the new name of Syria Palaestina, replacing the name of Judea.[62] The city was renamed Aelia Capitolina,[53][63] and rebuilt it in the style of a typical Roman town. Jews were prohibited from entering the city on pain of death, except for one day each year, during the holiday of Tisha B'Av. Taken together, these measures[64][61][65] (which also affected Jewish Christians)[66] essentially "secularized" the city.[67] Historical sources and archaeological evidence indicate that the rebuilt city was now inhabited by veterans of the Roman military and immigrants from the western parts of the empire.[68]

The ban against Jews was maintained until the 7th century,[69] though Christians would soon be granted an exemption: during the 4th century, the Roman emperor Constantine I ordered the construction of Christian holy sites in the city, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Burial remains from the Byzantine period are exclusively Christian, suggesting that the population of Jerusalem in Byzantine times probably consisted only of Christians.[70]

The Byzantine Madaba Map showing the city, dating to the 5th century AD, it is the oldest surviving depiction of Jerusalem.

The Byzantine Madaba Map showing the city, dating to the 5th century AD, it is the oldest surviving depiction of Jerusalem.In the 5th century, the eastern continuation of the Roman Empire, ruled from the recently renamed Constantinople, maintained control of the city. Within the span of a few decades, Jerusalem shifted from Byzantine to Persian rule, then back to Roman-Byzantine dominion. Following Sassanid Khosrau II's early 7th century push through Syria, his generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin attacked Jerusalem (Persian: Dej Houdkh) aided by the Jews of Palaestina Prima, who had risen up against the Byzantines.[71]

In the Siege of Jerusalem of 614, after 21 days of relentless siege warfare, Jerusalem was captured. Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sassanids and Jews slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, many at the Mamilla Pool,[72][73] and destroyed their monuments and churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This episode has been the subject of much debate between historians.[74] The conquered city would remain in Sassanid hands for some fifteen years until the Byzantine emperor Heraclius reconquered it in 629.[75]

Middle Ages Early Muslim period View of the Umayyad Dome of the Rock mosque commissioned in late 7th century AD, which was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and called "Jerusalem's most recognizable landmark".[76]

View of the Umayyad Dome of the Rock mosque commissioned in late 7th century AD, which was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and called "Jerusalem's most recognizable landmark".[76] Depiction of Jerusalem in the Byzantine Umm ar-Rasas mosaics, identified as Hagia Polis in Greek, the Holy City, during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate in 785.[77]

Depiction of Jerusalem in the Byzantine Umm ar-Rasas mosaics, identified as Hagia Polis in Greek, the Holy City, during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate in 785.[77]After the Muslim conquest of the Levant, Byzantine Jerusalem was taken by Umar ibn al-Khattab in 638 CE.[78] Among the first Muslims, it was referred to as Madinat bayt al-Maqdis ("City of the Temple"),[79] a name restricted to the Temple Mount. The rest of the city "was called Iliya, reflecting the Roman name given the city following the destruction of 70 CE: Aelia Capitolina".[80] Later the Temple Mount became known as al-Haram al-Sharif, "The Noble Sanctuary", while the city around it became known as Bayt al-Maqdis,[81] and later still, al-Quds al-Sharif "The Holy, Noble". The Islamization of Jerusalem began in the first year A.H. (623 CE), when Muslims were instructed to face the city while performing their daily prostrations and, according to Muslim religious tradition, Muhammad's night journey and ascension to heaven took place. After 13 years, the direction of prayer was changed to Mecca.[82][83] In 638 CE the Islamic Caliphate extended its dominion to Jerusalem.[84] With the Muslim conquest, Jews were allowed back into the city.[85] The Rashidun caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab signed a treaty with Christian Patriarch of Jerusalem Sophronius, assuring him that Jerusalem's Christian holy places and population would be protected under Muslim rule.[86] Christian-Arab tradition records that, when led to pray at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, one of the holiest sites for Christians, the caliph Umar refused to pray in the church so that Muslims would not request conversion of the church to a mosque.[87] He prayed outside the church, where the Mosque of Umar (Omar) stands to this day, opposite the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. According to the Gaullic bishop Arculf, who lived in Jerusalem from 679 to 688, the Mosque of Umar was a rectangular wooden structure built over ruins which could accommodate 3,000 worshipers.[88]

When the Arab armies under Umar went to Bayt Al-Maqdes in 637 CE, they searched for the site of al-masjid al-aqsa, "the farthest place of prayer/mosque", that was mentioned in the Quran and Hadith according to Islamic beliefs. Contemporary Arabic and Hebrew sources say the site was full of rubbish, and that Arabs and Jews cleaned it.[89] The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik commissioned the construction of a shrine on the Temple Mount, now known as the Dome of the Rock, in the late 7th century.[90] Two of the city's most-distinguished Arab citizens of the 10th-century were Al-Muqaddasi, the geographer, and Al-Tamimi, the physician. Al-Muqaddasi writes that Abd al-Malik built the edifice on the Temple Mount in order to compete in grandeur with Jerusalem's monumental churches.[88]

Over the next four hundred years, Jerusalem's prominence diminished as Arab powers in the region vied for control of the city.[91] Jerusalem was captured in 1073 by the Seljuk Turkish commander Atsız.[92] After Atsız was killed, the Seljuk prince Tutush I granted the city to Artuk Bey, another Seljuk commander. After Artuk's death in 1091 his sons Sökmen and Ilghazi governed in the city up to 1098 when the Fatimids recaptured the city.

A messianic Karaite movement to gather in Jerusalem took place at the turn of the millennium, leading to a "Golden Age" of Karaite scholarship there, which was only terminated by the Crusades.[93]

Crusader/Ayyubid period Medieval illustration of capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade, 1099.

Medieval illustration of capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade, 1099.In 1099, the Fatimid ruler expelled the native Christian population before Jerusalem was besieged by the soldiers of the First Crusade. After taking the solidly defended city by assault, the Crusaders massacred most of its Muslim and Jewish inhabitants, and made it the capital of their Kingdom of Jerusalem. The city, which had been virtually emptied, was recolonized by a variegated inflow of Greeks, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Georgians, Armenians, Syrians, Egyptians, Nestorians, Maronites, Jacobite Miaphysites, Copts and others, to block the return of the surviving Muslims and Jews. The north-eastern quarter was repopulated with Eastern Christians from the Transjordan.[94] As a result, by 1099 Jerusalem's population had climbed back to some 30,000.[95][failed verification]

In 1187, the city was wrested from the Crusaders by Saladin who permitted Jews and Muslims to return and settle in the city.[96] Under the terms of surrender, once ransomed, 60,000 Franks were expelled. The Eastern Christian populace was permitted to stay.[97] Under the Ayyubid dynasty of Saladin, a period of huge investment began in the construction of houses, markets, public baths, and pilgrim hostels as well as the establishment of religious endowments. However, for most of the 13th century, Jerusalem declined to the status of a village due to city's fall of strategic value and Ayyubid internecine struggles.[98]

From 1229 to 1244, Jerusalem peacefully reverted to Christian control as a result of a 1229 treaty agreed between the crusading Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and al-Kamil, the Ayyubid sultan of Egypt, that ended the Sixth Crusade.[99][100][101][102][103] The Ayyubids retained control of the Muslim holy places, and Arab sources suggest that Frederick was not permitted to restore Jerusalem's fortifications.

In 1244, Jerusalem was sacked by the Khwarezmian Tatars, who decimated the city's Christian population and drove out the Jews.[104] The Khwarezmian Tatars were driven out by the Ayyubids in 1247.

Mamluk periodFrom 1260[105] to 1516/17, Jerusalem was ruled by the Mamluks. In the wider region and until around 1300, many clashes occurred between the Mamluks on one side, and the crusaders and the Mongols, on the other side. The area also suffered from many earthquakes and black plague.[106] When Nachmanides visited in 1267 he found only two Jewish families, in a population of 2,000, 300 of whom were Christians, in the city.[107] The well-known and far-traveled lexicographer Fairuzabadi (1329–1414) spent ten years in Jerusalem.[108]

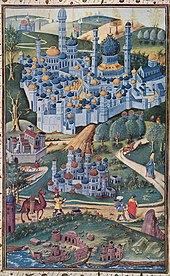

Jerusalem, from 'Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam' by Bernhard von Breydenbach (1486)

Jerusalem, from 'Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam' by Bernhard von Breydenbach (1486)The 13th to 15th centuries was a period of frequent building activity in the city, as evidenced by the 90 remaining structures from this time.[105] The city was also a significant site of Mamluk architectural patronage. The types of structures built included madrasas, libraries, hospitals, caravanserais, fountains (or sabils), and public baths.[105] Much of the building activity was concentrated around the edges of the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif.[105] Old gates to the Haram lost importance and new gates were built,[105] while significant parts of the northern and western porticoes along the edge of the Temple Mount plaza were built or rebuilt in this period.[109] Tankiz, the Mamluk amir in charge of Syria during the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad, built a new market called Suq al-Qattatin (Cotton Market) in 1336–7, along with the gate known as Bab al-Qattanin (Cotton Gate), which gave access to the Temple Mount from this market.[105][109] The late Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay also took interest in the city. He commissioned the building of the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya, completed in 1482, and the nearby Sabil of Qaytbay, built shortly after in 1482; both were located on the Temple Mount.[105][109] Qaytbay's monuments were the last major Mamluk constructions in the city.[109]: 589–612

Modern era Ottoman period (16th–19th centuries)In 1517, Jerusalem and its environs fell to the Ottoman Turks, who generally remained in control until 1917.[96] Jerusalem enjoyed a prosperous period of renewal and peace under Suleiman the Magnificent—including the rebuilding of magnificent walls around the Old City. Throughout much of Ottoman rule, Jerusalem remained a provincial, if religiously important centre, and did not straddle the main trade route between Damascus and Cairo.[110] The English reference book Modern history or the present state of all nations, written in 1744, stated that "Jerusalem is still reckoned the capital city of Palestine, though much fallen from its ancient grandeaur".[111]

1455 painting of the Holy Land. Jerusalem is viewed from the west; the octagonal Dome of the Rock stands left of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, shown as a church, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands on the left side of the picture.

1455 painting of the Holy Land. Jerusalem is viewed from the west; the octagonal Dome of the Rock stands left of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, shown as a church, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands on the left side of the picture.The Ottomans brought many innovations: modern postal systems run by the various consulates and regular stagecoach and carriage services were among the first signs of modernization in the city.[112] In the mid 19th century, the Ottomans constructed the first paved road from Jaffa to Jerusalem, and by 1892 the railroad had reached the city.[112]

With the annexation of Jerusalem by Muhammad Ali of Egypt in 1831, foreign missions and consulates began to establish a foothold in the city. In 1836, Ibrahim Pasha allowed Jerusalem's Jewish residents to restore four major synagogues, among them the Hurva.[113] In the countrywide Peasants' Revolt, Qasim al-Ahmad led his forces from Nablus and attacked Jerusalem, aided by the Abu Ghosh clan, and entered the city on 31 May 1834. The Christians and Jews of Jerusalem were subjected to attacks. Ibrahim's Egyptian army routed Qasim's forces in Jerusalem the following month.[114]

Ottoman rule was reinstated in 1840, but many Egyptian Muslims remained in Jerusalem and Jews from Algiers and North Africa began to settle in the city in growing numbers.[113] In the 1840s and 1850s, the international powers began a tug-of-war in Palestine as they sought to extend their protection over the region's religious minorities, a struggle carried out mainly through consular representatives in Jerusalem.[115] According to the Prussian consul, the population in 1845 was 16,410, with 7,120 Jews, 5,000 Muslims, 3,390 Christians, 800 Turkish soldiers and 100 Europeans.[113] The volume of Christian pilgrims increased under the Ottomans, doubling the city's population around Easter time.[116]

1844 daguerreotype by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (the earliest photograph of the city)

1844 daguerreotype by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (the earliest photograph of the city)In the 1860s, new neighbourhoods began to develop outside the Old City walls to house pilgrims and relieve the intense overcrowding and poor sanitation inside the city. The Russian Compound and Mishkenot Sha'ananim were founded in 1860,[117] followed by many others that included Mahane Israel (1868), Nahalat Shiv'a (1869), German Colony (1872), Beit David (1873), Mea Shearim (1874), Shimon HaZadiq (1876), Beit Ya'aqov (1877), Abu Tor (1880s), American-Swedish Colony (1882), Yemin Moshe (1891), and Mamilla, Wadi al-Joz around the turn of the century. In 1867 an American Missionary reports an estimated population of Jerusalem of 'above' 15,000, with 4,000 to 5,000 Jews and 6,000 Muslims. Every year there were 5,000 to 6,000 Russian Christian Pilgrims.[118] In 1872 Jerusalem became the centre of a special administrative district, independent of the Syria Vilayet and under the direct authority of Istanbul called the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem.[119]

The great number of Christian orphans resulting from the 1860 civil war in Mount Lebanon and the Damascus massacre led in the same year to the opening of the German Protestant Syrian Orphanage, better known as the Schneller Orphanage after its founder.[120] Until the 1880s there were no formal Jewish orphanages in Jerusalem, as families generally took care of each other. In 1881 the Diskin Orphanage was founded in Jerusalem with the arrival of Jewish children orphaned by a Russian pogrom. Other orphanages founded in Jerusalem at the beginning of the 20th century were Zion Blumenthal Orphanage (1900) and General Israel Orphan's Home for Girls (1902).[121]

Jewish immigration to PalestineDuring the reign of Sultan Bayezid II (1481–1512), the gates of Ottoman Turkey were opened to the Jews expelled from Spain, and in the days of Sultan Selim I, they were allowed to enter the territories he conquered, including Palestine.[122] Rabbi Moses Bassola, who visited Palestine in 1521–1522, testified that, largely due to this immigration, the Jewish community in Jerusalem grew and the deportees from Spain became the majority of the Jewish population in Jerusalem (which at that time numbered about 300 families).[122]

William McLean's 1918 plan was the first urban planning scheme for Jerusalem. It laid the foundations for what became West Jerusalem and East Jerusalem.[123]

William McLean's 1918 plan was the first urban planning scheme for Jerusalem. It laid the foundations for what became West Jerusalem and East Jerusalem.[123] Jerusalem on VE Day, 8 May 1945

Jerusalem on VE Day, 8 May 1945In 1917 after the Battle of Jerusalem, the British Army, led by General Edmund Allenby, captured the city.[124] In 1922, the League of Nations at the Conference of Lausanne entrusted the United Kingdom to administer Palestine, neighbouring Transjordan, and Iraq beyond it.

From 1922 to 1948 the total population of the city rose from 52,000 to 165,000, comprising two-thirds Jews and one-third Arabs (Muslims and Christians).[125] Relations between Arab Christians and Muslims and the growing Jewish population in Jerusalem deteriorated, resulting in recurring unrest. In Jerusalem, in particular, Arab riots occurred in 1920 and in 1929. Under the British, new garden suburbs were built in the western and northern parts of the city[126][127] and institutions of higher learning such as the Hebrew University were founded.[128]

Contemporary era Divided city: Jordanian and Israeli rule (1948–1967)As the British Mandate for Palestine was expiring, the 1947 UN Partition Plan recommended "the creation of a special international regime in the City of Jerusalem, constituting it as a corpus separatum under the administration of the UN."[129] The international regime (which also included the city of Bethlehem) was to remain in force for a period of ten years, whereupon a referendum was to be held in which the residents were to decide the future regime of their city.[130] However, this plan was not implemented, as the 1948 war erupted, while the British withdrew from Palestine and Israel declared its independence.[131]

In contradiction to the Partition Plan, which envisioned a city separated from the Arab state and the Jewish state, Israel took control of the area which later would become West Jerusalem, along with major parts of the Arab territory allotted to the future Arab State; Jordan took control of East Jerusalem, along with the West Bank. The war led to displacement of Arab and Jewish populations in the city. The 1,500 residents of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City were expelled and a few hundred taken prisoner when the Arab Legion captured the quarter on 28 May.[132][133] Arab residents of Katamon, Talbiya, and the German Colony were driven from their homes. By the time of the armistice that ended active fighting, Israel had control of 12 of Jerusalem's 15 Arab residential quarters. An estimated minimum of 30,000 people had become refugees.[134][135]

The war of 1948 resulted in the division of Jerusalem, so that the old walled city lay entirely on the Jordanian side of the line. A no-man's land between East and West Jerusalem came into being in November 1948: Moshe Dayan, commander of the Israeli forces in Jerusalem, met with his Jordanian counterpart Abdullah el-Tell in a deserted house in Jerusalem's Musrara neighbourhood and marked out their respective positions: Israel's position in red and Jordan's in green. This rough map, which was not meant as an official one, became the final line in the 1949 Armistice Agreements, which divided the city and left Mount Scopus as an Israeli exclave inside East Jerusalem.[136] Barbed wire and concrete barriers ran down the centre of the city, passing close by Jaffa Gate on the western side of the old walled city, and a crossing point was established at Mandelbaum Gate slightly to the north of the old walled city. Military skirmishes frequently threatened the ceasefire.

After the establishment of the state of Israel, Jerusalem was declared its capital city.[137] Jordan formally annexed East Jerusalem in 1950, subjecting it to Jordanian law, and in 1953 declared it the "second capital" of Jordan.[131][138][139] Only the United Kingdom and Pakistan formally recognized such annexation, which, in regard to Jerusalem, was on a de facto basis.[140] Some scholars argue that the view that Pakistan recognized Jordan's annexation is dubious.[141][142]

After 1948, since the old walled city in its entirety was to the east of the armistice line, Jordan was able to take control of all the holy places therein. While Muslim holy sites were maintained and renovated,[143] contrary to the terms of the armistice agreement, Jews were denied access to Jewish holy sites, many of which were destroyed or desecrated. Jordan allowed only very limited access to Christian holy sites,[144] and restrictions were imposed on the Christian population that led many to leave the city. Of the 58 synagogues in the Old City, half were either razed or converted to stables and hen-houses over the course of the next 19 years, including the Hurva and the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue. The 3,000-year-old[145] Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery was desecrated, with gravestones used to build roads, latrines and Jordanian army fortifications. 38,000 graves in the Jewish Cemetery were destroyed, and Jews were forbidden from being buried there.[146][147] The Western Wall was transformed into an exclusively Muslim holy site associated with al-Buraq.[148] Israeli authorities neglected to protect the tombs in the Muslim Mamilla Cemetery in West Jerusalem, which contains the remains of figures from the early Islamic period,[149] facilitating the creation of a parking lot and public lavatories in 1964.[150] Many other historic and religiously significant buildings were demolished and replaced by modern structures during the Jordanian occupation.[151] During this period, the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque underwent major renovations.[152]

During the 1948 war, the Jewish residents of Eastern Jerusalem were expelled by Jordan's Arab Legion. Jordan allowed Arab Palestinian refugees from the war to settle in the vacated Jewish Quarter, which became known as Harat al-Sharaf.[153] In 1966 the Jordanian authorities relocated 500 of them to the Shua'fat refugee camp as part of plans to turn the Jewish quarter into a public park.[154][155]

Map of East Jerusalem (2010)

Map of East Jerusalem (2010)In 1967, the Six-Day War erupted between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Jordan joined Egypt and attacked Israeli-held West Jerusalem on the war's second day. After hand-to-hand fighting between Israeli and Jordanian soldiers on the Temple Mount, the Israel Defense Forces occupied East Jerusalem, along with the entire West Bank. On 27 June 1967, three weeks after the war ended, in what Israel terms the reunification of Jerusalem, Israel extended its law and jurisdiction to East Jerusalem, including the city's Christian and Muslim holy sites, along with some nearby West Bank territory which comprised 28 Palestinian villages, incorporating it into the Jerusalem Municipality,[156] although it carefully avoided using the term "annexation". On 10 July, Foreign Minister Abba Eban explained to the UN Secretary General: "The term 'annexation' which was used by supporters of the vote is not accurate. The steps that were taken [by Israel] relate to the integration of Jerusalem in administrative and municipal areas, and served as a legal basis for the protection of the holy places of Jerusalem."[157] Israel conducted a census of Arab residents in the areas annexed. Residents were given permanent residency status and the option of applying for Israeli citizenship. Since 1967, new Jewish residential areas have mushroomed in the eastern sector, while no new Palestinian neighbourhoods have been created.[158]

Jewish and Christian access to the holy sites inside the old walled city was restored. Israel left the Temple Mount under the jurisdiction of an Islamic waqf, but opened the Western Wall to Jewish access. The Moroccan Quarter, which was located adjacent to the Western Wall, was evacuated and razed[159] to make way for a plaza for those visiting the wall.[160] On 18 April 1968, an expropriation order by the Israeli Ministry of Finance more than doubled the size of the Jewish Quarter, evicting its Arab residents and seizing over 700 buildings of which 105 belonged to Jewish inhabitants prior to the Jordanian occupation of the city.[citation needed] The order designated these areas for public use, but they were intended for Jews alone.[161] The government offered 200 Jordanian dinars to each displaced Arab family.

After the Six-Day War the population of Jerusalem increased by 196%. The Jewish population grew by 155%, while the Arab population grew by 314%. The proportion of the Jewish population fell from 74% in 1967 to 72% in 1980, to 68% in 2000, and to 64% in 2010.[162] Israeli Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon proposed building a ring of Jewish neighbourhoods around the city's eastern edges. The plan was intended to make East Jerusalem more Jewish and prevent it from becoming part of an urban Palestinian bloc stretching from Bethlehem to Ramallah. On 2 October 1977, the Israeli cabinet approved the plan, and seven neighbourhoods were subsequently built on the city's eastern edges. They became known as the Ring Neighbourhoods. Other Jewish neighbourhoods were built within East Jerusalem, and Israeli Jews also settled in Arab neighbourhoods.[163][164]

Shimon Peres, Hosni Mubarak and King Hussein at funeral of Yitzhak Rabin in Jerusalem in 1995

Shimon Peres, Hosni Mubarak and King Hussein at funeral of Yitzhak Rabin in Jerusalem in 1995In 1993, the Oslo I Accord was signed between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. The agreement led to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority. The Jerusalem Governorate was notified by this authority. [165] Only parts of few neighborhoods were allotted to the Palestinian Authority and this peace talks didn't solve the overall problem of Jerusalem.[166]

The annexation of East Jerusalem was met with international criticism. The Israeli Foreign Ministry disputes that the annexation of Jerusalem was a violation of international law.[167][168] The final status of Jerusalem has been one of the most important areas of discord between Palestinian and Israeli negotiators for peace. Areas of discord have included whether the Palestinian flag can be raised over areas of Palestinian custodianship and the specificity of Israeli and Palestinian territorial borders.[169]

Add new comment