كنيسة القيامة

( Church of the Holy Sepulchre )

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection, is a fourth-century church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. It is considered to be the holiest site for Christians in the world, as it has been the most important pilgrimage site for Christianity since the fourth century.

According to traditions dating back to the fourth century, it contains two sites considered holy in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus's empty tomb, which is where he was buried and resurrected. In earlier times, the site was used as a Jewish burial ground, upon which a pagan temple was built. The church and rotunda, built under Constantine in the 4th century and destroyed by al-Hakim in 1009, were later reconstructed with modifications by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos and the Crusaders, resulting in a significant departure from the original stru...Read more

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection, is a fourth-century church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. It is considered to be the holiest site for Christians in the world, as it has been the most important pilgrimage site for Christianity since the fourth century.

According to traditions dating back to the fourth century, it contains two sites considered holy in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus's empty tomb, which is where he was buried and resurrected. In earlier times, the site was used as a Jewish burial ground, upon which a pagan temple was built. The church and rotunda, built under Constantine in the 4th century and destroyed by al-Hakim in 1009, were later reconstructed with modifications by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos and the Crusaders, resulting in a significant departure from the original structure. The tomb itself is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicule.

Within the church proper are the last four stations of the Cross of the Via Dolorosa, representing the final episodes of the Passion of Jesus. The church has been a major Christian pilgrimage destination since its creation in the fourth century, as the traditional site of the resurrection of Christ, thus its original Greek name, Church of the Anastasis ('Resurrection').

The Status Quo, an understanding between religious communities dating to 1757, applies to the site. Control of the church itself is shared among several Christian denominations and secular entities in complicated arrangements essentially unchanged for over 160 years, and some for much longer. The main denominations sharing property over parts of the church are the Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic, and to a lesser degree the Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopian Orthodox churches.

Following the siege of Jerusalem in AD 70 during the First Jewish–Roman War, Jerusalem had been reduced to ruins. In AD 130, the Roman emperor Hadrian began the building of a Roman colony, the new city of Aelia Capitolina, on the site. Circa AD 135, he ordered that a cave containing a rock-cut tomb[a] be filled in to create a flat foundation for a temple dedicated to Jupiter or Venus.[5][6] The temple remained until the early fourth century.[7][8]

Constantine and Macarius: context for the first sanctuaryAfter seeing a vision of a cross in the sky in 312,[9] Constantine the Great began to favor Christianity and signed the Edict of Milan legalising the religion. The Bishop of Jerusalem Macarius asked Constantine for permission to start an excavation to search for the tomb. With the help of Bishop of Caesarea Eusebius and Bishop of Jerusalem Macarius, three crosses were found near a tomb; one which allegedly cured people of death was presumed to be the True Cross Jesus was crucified on, leading the Romans to believe that they had found Calvary.[9][10]

Constantine ordered in about 326 that the temple to Jupiter/Venus be replaced by a church.[5] After the temple was torn down and its ruins removed, the soil was removed from the cave, revealing a rock-cut tomb that Macarius identified as the burial site of Jesus.[11][12][13][14]

First sanctuary (4th century)

A shrine was built on the site of the tomb Macarius had identified as that of Jesus, enclosing the rock tomb walls within its own.[16][4][17][b]

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, planned by the architect Zenobius,[18] was built as separate constructs over two holy sites:

a rotunda called the Anastasis ('Resurrection'), where Macarius believed Jesus to have been buried,[11][better source needed] and; the great basilica (also known as Martyrium),[19] across a courtyard to the east (an enclosed colonnaded atrium, known as the Triportico) with the traditional site of Calvary in one corner.[6][20] Diagram of a possible church layout (facing west) published in 1956 by Kenneth John Conant

Diagram of a possible church layout (facing west) published in 1956 by Kenneth John ConantThe Church of the Holy Sepulchre site has been recognized since early in the fourth century as the place where Jesus was crucified, buried, and rose from the dead.[21][c] The church was consecrated on 13 September 335.[21][d]

In 327, Constantine and Helena separately commissioned the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem to commemorate the birth of Jesus.

Damage and destruction (614–1009)The Constantinian sanctuary in Jerusalem was destroyed by a fire in May of 614, when the Sassanid Empire, under Khosrau II,[9] invaded Jerusalem and captured the True Cross. In 630, the Emperor Heraclius rebuilt the church after recapturing the city.[23]

After Jerusalem came under Islamic rule, it remained a Christian church, with the early Muslim rulers protecting the city's Christian sites, prohibiting their destruction or use as living quarters. A story reports that the caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab visited the church and stopped to pray on the balcony, but at the time of prayer, turned away from the church and prayed outside. He feared that future generations would misinterpret this gesture, taking it as a pretext to turn the church into a mosque. Eutychius of Alexandria adds that Umar wrote a decree saying that Muslims would not inhabit this location. The building suffered severe damage from an earthquake in 746.[23]

Early in the ninth century, another earthquake damaged the dome of the Anastasis. The damage was repaired in 810 by Patriarch Thomas I. In 841, the church suffered a fire. In 935, the Christians prevented the construction of a Muslim mosque adjacent to the Church. In 938, a new fire damaged the inside of the basilica and came close to the rotunda. In 966, due to a defeat of Muslim armies in the region of Syria, a riot broke out, which was followed by reprisals. The basilica was burned again. The doors and roof were burnt, and Patriarch John VII was murdered.[citation needed]

On 18 October 1009, Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the complete destruction of the church as part of a more general campaign against Christian places of worship in Palestine and Egypt.[e] The damage was extensive, with few parts of the early church remaining, and the roof of the rock-cut tomb damaged; the original shrine was destroyed.[16] Some partial repairs followed.[24] Christian Europe reacted with shock: it was a spur to expulsions of Jews and, later on, the Crusades.[25][26][dubious ]

Reconstruction (11th century)In wide-ranging negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire in 1027–1028, an agreement was reached whereby the new Caliph Ali az-Zahir (al-Hakim's son) agreed to allow the rebuilding and redecoration of the church.[27] The rebuilding was finally completed during the tenures of Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos and Patriarch Nicephorus of Jerusalem in 1048.[28] As a concession, the mosque in Constantinople was reopened and the khutba sermons were to be pronounced in az-Zahir's name.[27] Muslim sources say a by-product of the agreement was the renunciation of Islam by many Christians who had been forced to convert under al-Hakim's persecutions. In addition, the Byzantines, while releasing 5,000 Muslim prisoners, made demands for the restoration of other churches destroyed by al-Hakim and the reestablishment of a patriarch in Jerusalem. Contemporary sources credit the emperor with spending vast sums in an effort to restore the Church of the Holy Sepulchre after this agreement was made.[27] Still, "a total replacement was far beyond available resources. The new construction was concentrated on the rotunda and its surrounding buildings: the great basilica remained in ruins."[24]

The rebuilt church site consisted of "a court open to the sky, with five small chapels attached to it."[29][failed verification] The chapels were east of the court of resurrection (when reconstructed, the location of the tomb was under open sky), where the western wall of the great basilica had been. They commemorated scenes from the passion, such as the location of the prison of Christ and his flagellation, and presumably were so placed because of the difficulties of free movement among shrines in the city streets. The dedication of these chapels indicates the importance of the pilgrims' devotion to the suffering of Christ. They have been described as "a sort of Via Dolorosa in miniature" since little or no rebuilding took place on the site of the great basilica. Western pilgrims to Jerusalem during the 11th century found much of the sacred site in ruins.[24][failed verification] Control of Jerusalem, and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, continued to change hands several times between the Fatimids and the Seljuk Turks (loyal to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad) until the Crusaders' arrival in 1099.[30]

Crusader period (1099–1244) BackgroundMany historians maintain that the main concern of Pope Urban II, when calling for the First Crusade, was the threat to Constantinople from the Seljuk invasion of Asia Minor in response to the appeal of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Historians agree that the fate of Jerusalem and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was also of concern, if not the immediate goal of papal policy in 1095. The idea of taking Jerusalem gained more focus as the Crusade was underway. The rebuilt church site was taken from the Fatimids (who had recently taken it from the Abbasids) by the knights of the First Crusade on 15 July 1099.[24]

The First Crusade was envisioned as an armed pilgrimage, and no crusader could consider his journey complete unless he had prayed as a pilgrim at the Holy Sepulchre. The classical theory is that Crusader leader Godfrey of Bouillon, who became the first Latin ruler of Jerusalem, decided not to use the title "king" during his lifetime, and declared himself Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ('Protector [or Defender] of the Holy Sepulchre').

According to the German priest and pilgrim Ludolf von Sudheim, the keys of the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre were in hands of the "ancient Georgians", and the food, alms, candles and oil for lamps were given to them by the pilgrims at the south door of the church.[31]

Crusaders: reconstruction (12th century) and ownershipBy the Crusader period, a cistern under the former basilica was rumoured to have been where Helena had found the True Cross, and began to be venerated as such; the cistern later became the Chapel of the Invention of the Cross, but there is no evidence of the site's identification before the 11th century, and modern archaeological investigation has now dated the cistern to 11th-century repairs by Monomachos.[8]

William of Tyre, chronicler of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, reports on the rebuilding of the church in the mid-12th century. The Crusaders investigated the eastern ruins on the site, occasionally excavating through the rubble, and while attempting to reach the cistern, they discovered part of the original ground level of Hadrian's temple enclosure; they transformed this space into a chapel dedicated to Helena, widening their original excavation tunnel into a proper staircase.[32]

Crusader graffiti in the church: crosses engraved in the staircase leading down to the Chapel of Saint Helena[33]

Crusader graffiti in the church: crosses engraved in the staircase leading down to the Chapel of Saint Helena[33]The Crusaders began to refurnish the church in Romanesque style and added a bell tower.[32] These renovations unified the small chapels on the site[clarification needed] and were completed during the reign of Queen Melisende in 1149, placing all the holy places under one roof for the first time.[32]

The church became the seat of the first Latin patriarchs and the site of the kingdom's scriptorium.[32]

Eight 11th- and 12th-century Crusader leaders (Godfrey, Baldwin I, Baldwin II, Fulk, Baldwin III, Amalric, Baldwin IV and Baldwin V — the first eight rulers of the Kingdom of Jerusalem) were buried in the south transept and inside the Chapel of Adam.[34][35][36] The royal tombs were looted during the Khwarizmian sack of Jerusalem in 1244 but probably remained mostly intact until 1808 when a fire damaged the church. The tombs may have been destroyed by the fire, or during renovations by the Greek Orthodox custodians of the church in 1809-1810. The remains of the kings may still be in unmarked pits under the church's pavement.[37]

The church was lost to Saladin,[32] along with the rest of the city, in 1187, although the treaty established after the Third Crusade allowed Christian pilgrims to visit the site. Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220–50) regained the city and the church by treaty in the 13th century while under a ban of excommunication, with the consequence that the holiest church in Christianity was laid under interdict.[citation needed] The church seems to have been largely in the hands of Greek Orthodox patriarch Athanasius II of Jerusalem (c. 1231–47) during the last period of Latin control over Jerusalem.[38] Both city and church were captured by the Khwarezmians in 1244.[32]

Ottoman periodThere was certainly a recognisable Nestorian (Church of the East) presence at the Holy Sepulchre from the years 1348 through 1575, as contemporary Franciscan accounts indicate.[39] The Franciscan friars renovated the church in 1555, as it had been neglected despite increased numbers of pilgrims. The Franciscans rebuilt the Aedicule, extending the structure to create an antechamber.[40] A marble shrine commissioned by Friar Boniface of Ragusa was placed to envelop the remains of Christ's tomb,[16] probably to prevent pilgrims from touching the original rock or taking small pieces as souvenirs.[17] A marble slab was placed over the limestone burial bed where Jesus's body is believed to have lain.[16]

After the renovation of 1555, control of the church oscillated between the Franciscans and the Orthodox, depending on which community could obtain a favorable firman from the "Sublime Porte" at a particular time, often through outright bribery. Violent clashes were not uncommon. There was no agreement about this question, although it was discussed at the negotiations to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699.[41] During the Holy Week of 1757, Orthodox Christians reportedly took over some of the Franciscan-controlled church. This may have been the cause of the sultan's firman (decree) later developed into the Status Quo.[42][better source needed][f]

A fire severely damaged the structure again in 1808,[16] causing the dome of the Rotunda to collapse and smashing the Aedicule's exterior decoration. The Rotunda and the Aedicule's exterior were rebuilt in 1809–10 by architect Nikolaos Ch. Komnenos of Mytilene in the contemporary Ottoman Baroque style.[43] The interior of the antechamber, now known as the Chapel of the Angel,[g] was partly rebuilt to a square ground plan in place of the previously semicircular western end.

Another decree in 1853 from the sultan solidified the existing territorial division among the communities and solidified the Status Quo for arrangements to "remain in their present state", requiring consensus to make even minor changes.[44][f]

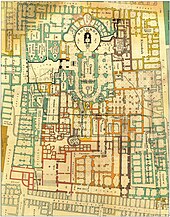

Floorplan, illustrated by Conrad Schick (1863)

Floorplan, illustrated by Conrad Schick (1863)The dome was restored by Catholics, Greeks, and Turks in 1868, being made of iron ever since.[46]

British Mandate periodBy the time of the British Mandate for Palestine following the end of World War I, the cladding of red limestone applied to the Aedicule by Komnenos had deteriorated badly and was detaching from the underlying structure; from 1947 until restoration work in 2016–17, it was held in place with an exterior scaffolding of iron girders installed by the British authorities.[47]

After the care of the British Empire, the Church of England had an important role in the appropriation of the Holy Sepulcher, such as funds for the maintenance of external infrastructures, and the abolition of territorial claims near the Temple of the Holy Sepulcher, the Protestant Church allowed to carry out the elimination of taxes from the Holy Sepulcher, currently the Anglican and Lutheran dioceses of Jerusalem are allowed to attend Armenian cults.

Jordanian and Israeli periods Diagram of the modern church showing the traditional site of Calvary and the Tomb of Jesus

Diagram of the modern church showing the traditional site of Calvary and the Tomb of JesusIn 1948, Jerusalem was divided between Israel and Jordan and the Old City with the church were made part of Jordan. In 1967, Israeli forces captured East Jerusalem in the Six Day War, and that area has remained under Israeli control ever since. Under Israeli rule, legal arrangements relating to the churches of East Jerusalem were maintained in coordination with the Jordanian government. The dome at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was restored again in 1994–97 as part of extensive modern renovations that have been ongoing since 1959. During the 1970–78 restoration works and excavations inside the building, and under the nearby Muristan bazaar, it was found that the area was originally a quarry, from which white meleke limestone was struck.[48]

Chapel of St. VartanEast of the Chapel of Saint Helena, the excavators discovered a void containing a second-century[dubious ] drawing of a Roman pilgrim ship,[49] two low walls supporting the platform of Hadrian's second-century temple, and a higher fourth-century wall built to support Constantine's basilica.[40][50] After the excavations of the early 1970s, the Armenian authorities converted this archaeological space into the Chapel of Saint Vartan, and created an artificial walkway over the quarry on the north of the chapel, so that the new chapel could be accessed (by permission) from the Chapel of Saint Helena.[50]

Aedicule restorationAfter seven decades of being held together by steel girders, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) declared the visibly deteriorating Aedicule structure unsafe. A restoration of the Aedicule was agreed upon and executed from May 2016 to March 2017. Much of the $4 million project was funded by the World Monuments Fund, as well as $1.3 million from Mica Ertegun and a significant sum from King Abdullah II of Jordan.[47][51] The existence of the original limestone cave walls within the Aedicule was confirmed, and a window was created to view this from the inside.[17] The presence of moisture led to the discovery of an underground shaft resembling an escape tunnel carved into the bedrock, seeming to lead from the tomb.[4][h] For the first time since at least 1555, on 26 October 2016, marble cladding that protects the supposed burial bed of Jesus was removed.[17][52] Members of the National Technical University of Athens were present. Initially, only a layer of debris was visible. This was cleared in the next day, and a partially broken marble slab with a Crusader-style cross carved was revealed.[4] By the night of 28 October, the original limestone burial bed was shown to be intact. The tomb was resealed shortly thereafter.[17] Mortar from just above the burial bed was later dated to the mid-fourth century.[53]

2020 pandemicOn 25 March 2020, Israeli health officials ordered the site closed to the public due to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the keeper of the keys, it was the first such closure since 1349, during the Black Death.[54] Clerics continued regular prayers inside the building, and it reopened to visitors two months later, on 24 May.[55]

Crusader altar slab discovered (2022)During church renovations in 2022, a stone slab covered in modern graffiti was moved from a wall, revealing Cosmatesque-style decoration on one face. According to an IAA archaeologist, the decoration was once inlaid with pieces of glass and fine marble; it indicates that the relic was the front of the church's high altar from the Crusader era (c. 1149), which was later used by the Greek Orthodox until being damaged in the 1808 fire.[56]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment