جامعة القرويين

( University of al-Qarawiyyin )

The University of al-Qarawiyyin (Arabic: جامعة القرويين, romanized: Jāmiʻat al-Qarawīyīn; Berber languages: ⵜⴰⵙⴷⴰⵡⵉⵜ ⵏ ⵍⵇⴰⵕⴰⵡⵉⵢⵉⵏ; French: Université Al Quaraouiyine), also written Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine, is a university located in Fez, Morocco. It was founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 857–859 and subsequently became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the Islamic Golden Age. It was incorporated into Morocco's modern state university system in 1963 and officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" two years later. The mosque building itself is also a significant complex of historical Moroccan and Islamic architecture that features elements from many different periods of Moroccan history.

Scholars consider al-Qarawiyyin to have...Read more

The University of al-Qarawiyyin (Arabic: جامعة القرويين, romanized: Jāmiʻat al-Qarawīyīn; Berber languages: ⵜⴰⵙⴷⴰⵡⵉⵜ ⵏ ⵍⵇⴰⵕⴰⵡⵉⵢⵉⵏ; French: Université Al Quaraouiyine), also written Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine, is a university located in Fez, Morocco. It was founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 857–859 and subsequently became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the Islamic Golden Age. It was incorporated into Morocco's modern state university system in 1963 and officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" two years later. The mosque building itself is also a significant complex of historical Moroccan and Islamic architecture that features elements from many different periods of Moroccan history.

Scholars consider al-Qarawiyyin to have been effectively run as a madrasa until after World War II. Many scholars distinguish this status from the status of "university", which they view as a distinctly European invention. They date al-Qarawiyyin's transformation from a madrasa into a university to its modern reorganization in 1963. Some sources, such as UNESCO and the Guinness World Records, have cited al-Qarawiyyin as the oldest university or oldest continually operating higher learning institution in the world.

Education at the University of al-Qarawiyyin concentrates on the Islamic religious and legal sciences with a heavy emphasis on, and particular strengths in, Classical Arabic grammar/linguistics and Maliki Sharia, though lessons on non-Islamic subjects are also offered to students. Teaching is still delivered in the traditional methods. The university is attended by students from all over Morocco and Muslim West Africa, with some also coming from further abroad. Women were first admitted to the institution in the 1940s.

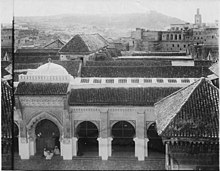

View of the Qarawiyyin Mosque on the skyline of central Fes el-Bali: the green-tiled roofs of the prayer hall and the minaret (white tower on the left) are visible.Foundation of the mosque

View of the Qarawiyyin Mosque on the skyline of central Fes el-Bali: the green-tiled roofs of the prayer hall and the minaret (white tower on the left) are visible.Foundation of the mosque

In the 9th century, Fez was the capital of the Idrisid dynasty, considered to be the first Moroccan Islamic state.[1] According to one of the major early sources on this period, the Rawd al-Qirtas by Ibn Abi Zar, al-Qarawiyyin was founded as a mosque in 857 or 859 by Fatima al-Fihri, the daughter of a wealthy merchant named Mohammed al-Fihri.[2][3][4][5][6][7]: 9 [8]: 40 The al-Fihri family had migrated from Kairouan (hence the name of the mosque), Tunisia to Fez in the early 9th century, joining a community of other migrants from Kairouan who had settled in a western district of the city. Fatima and her sister Mariam, both of whom were well educated, inherited a large amount of money from their father. Fatima vowed to spend her entire inheritance to build a mosque suitable for her community.[9]: 48–49 Similarly, her sister Mariam is also reputed to have founded al-Andalusiyyin Mosque the same year.[10][9]

This foundation narrative has been questioned by some modern historians who see the symmetry of two sisters founding the two most famous mosques of Fez as too convenient and likely originating from a legend.[9]: 48–49 [11][8]: 42 Ibn Abi Zar is also judged by contemporary historians to be a relatively unreliable source.[11] One of the biggest challenges to this story is a foundation inscription that was rediscovered during renovations to the mosque in the 20th century, previously hidden under layers of plaster for centuries. This inscription, carved onto cedar wood panels and written in a Kufic script very similar to foundation inscriptions in 9th-century Tunisia, was found on a wall above the probable site of the mosque's original mihrab (prior to the building's later expansions). The inscription, recorded and deciphered by Gaston Deverdun, proclaims the foundation of "this mosque" (Arabic: "هذا المسجد") by Dawud ibn Idris (a son of Idris II who governed this region of Morocco at the time) in Dhu al-Qadah 263 AH (July–August of 877 CE).[12] Deverdun suggested the inscription may have come from another unidentified mosque and was moved here at a later period (probably 15th or 16th century) when the veneration of the Idrisids was resurgent in Fez, and such relics would have held enough religious significance to be reused in this way.[12] However, Chafik Benchekroun argued more recently that a more likely explanation is that this inscription is the original foundation inscription of al-Qarawiyyin itself and that it might have been covered up in the 12th century just before the Almohads' arrival in the city.[11] Based on this evidence and on the many doubts about Ibn Abi Zar's narrative, he argues that Fatima al-Fihri is quite possibly a legendary figure rather than a historical one.[11] Péter T. Nagy has also stated that the uncovered foundation inscription is more convincing evidence of the mosque's original foundation date than the traditional historiographical narrative.[13]

Early historySome scholars suggest that some teaching and instruction probably took place at al-Qarawiyyin Mosque from a very early period[14][9]: 453 or from its beginning.[15]: 287 [16]: 71 [17] Major mosques in the early Islamic period were typically multi-functional buildings where teaching and education took place alongside other religious and civic activities.[18][19] The al-Andalusiyyin Mosque, in the district across the river, may have also served a similar role up until at least the Marinid period, though it never equaled the Qarawiyyin's later prestige.[9]: 453 It is unclear at what time al-Qarawiyyin began to act more formally as an educational institution, partly because of the limited historical sources that pertain to its early period.[15][20][9] The most relevant major historical texts like the Rawd al-Qirtas by Ibn Abi Zar and the Zahrat al-As by Abu al-Hasan Ali al-Jazna'i do not provide any clear details on the history of teaching at the mosque,[9]: 453 though al-Jazna'i (who lived in the 14th century) mentions that teaching had taken place there before his time.[21]: 175 Otherwise, the earliest mentions of halaqa (circles) for learning and teaching may not have been until the 10th or the 12th century.[22][15] Historian Abdelhadi Tazi indicates the earliest clear evidence of teaching at al-Qarawiyyin in 1121.[14]: 112 Moroccan historian Mohammed Al-Manouni believes that the mosque acquired its function as a teaching institution during the reign of the Almoravids (1040–1147).[20] Historian Évariste Lévi-Provençal dates the beginning of teaching to the Marinid period (1244–1465).[23]

In the 10th century, the Idrisid dynasty fell from power and Fez was contested between the Fatimid and Córdoban Umayyad caliphates and their allies.[1] During this period, the Qarawiyyin Mosque progressively grew in prestige. At some point the khutba (Friday sermon) was transferred from the Shurafa Mosque of Idris II (today the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II) to the Qarawiyyin Mosque, granting it the status of Friday mosque (the community's main mosque). This transfer happened either in 919 or in 933, both dates that correspond to brief periods of Fatimid domination over the city, and suggests that the transfer may have occurred by Fatimid initiative.[7]: 12 The mosque and its learning institution continued to enjoy the respect of political elites, with the mosque itself being significantly expanded by the Almoravids and repeatedly embellished under subsequent dynasties.[7] Tradition was established that all the other mosques in Fez based the timing of their call to prayer (adhan) according to that of al-Qarawiyyin.[24]

Apogee during the Marinid period Reconstruction of the 14th-century water clock from the dar al-muwaqqit of the Qarawiyyin Mosque (on display at the Istanbul Museum of the History of Science and Technology in Islam)

Reconstruction of the 14th-century water clock from the dar al-muwaqqit of the Qarawiyyin Mosque (on display at the Istanbul Museum of the History of Science and Technology in Islam)Many scholars consider al-Qarawiyyin's high point as an intellectual and scholarly center to be in the 13th and 14th centuries, when the curriculum was at its broadest and its prestige had reached new heights after centuries of expansion and elite patronage.[16][24][20]: 141 Among the subjects taught around this period or shortly after were traditional religious subjects such as the Quran and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), and other sciences like grammar, rhetoric, logic, medicine, mathematics, astronomy and geography.[20][15][16][9]: 455 By contrast, some subjects like alchemy/chemistry were never officially taught as they were considered too unorthodox.[9]: 455

The Al-Attarine Madrasa (founded in 1323), just north of the Qarawiyyin Mosque

The Al-Attarine Madrasa (founded in 1323), just north of the Qarawiyyin MosqueStarting in the late 13th century, and especially in the 14th century, the Marinid dynasty was responsible for constructing a number of formal madrasas in the areas around al-Qarawiyyin's main building. The first of these was the Saffarin Madrasa in 1271, followed by al-Attarine in 1323, and the Mesbahiya Madrasa in 1346.[25] A larger but much later madrasa, the Cherratine Madrasa, was also built nearby in 1670.[26] These madrasas taught their own courses and sometimes became well-known institutions, but they usually had narrower curricula or specializations.[24]: 141 [27] One of their most important functions seems to have been to provide housing for students from other towns and cities – many of them poor – who needed a place to stay while studying at al-Qarawiyyin.[28]: 137 [24]: 110 [9]: 463 Thus, these buildings acted as complimentary or auxiliary institutions to al-Qarawiyyin itself, which remained the center of intellectual life in the city.

Al-Qarawiyyin also compiled a large selection of manuscripts that were kept at a library founded by the Marinid sultan Abu Inan Faris in 1349.[7][29] The collection housed numerous works from the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the Middle East.[30] Part of the collection was gathered decades earlier by Sultan Abu Yusuf Ya'qub (ruled 1258–1286), who persuaded Sancho IV of Castile to hand over a number of works from the libraries of Seville, Córdoba, Almeria, Granada, and Malaga in al-Andalus/Spain. Abu Yusuf initially housed these in the nearby Saffarin Madrasa (which he had recently built), but later moved them to al-Qarawiyyin.[30] Among the most precious manuscripts currently housed in the library are volumes from the Al-Muwatta of Malik written on gazelle parchment,[31] a copy of the Sirat by Ibn Ishaq,[31] a 9th-century Quran manuscript (also written on gazelle parchment),[24]: 148 a copy of the Quran given by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur in 1602,[31] a copy of Ibn Rushd's Al-Bayan Wa-al-Tahsil wa-al-Tawjih (a commentary on Maliki fiqh) dating from 1320,[32][24]: 143 and the original copy of Ibn Khaldun's book Al-'Ibar (including the Muqaddimah) gifted by the author in 1396.[31][27] Recently rediscovered in the library is an ijazah certificate, written on deer parchment, which some scholars claim to be the oldest surviving predecessor of a Medical Doctorate degree, issued to a man called Abdellah Ben Saleh Al Koutami in 1207 CE under the authority of three other doctors and in the presence of the chief qadi (judge) of the city and two other witnesses.[33][34] The library was managed by a qayim or conservator, who oversaw the maintenance of the collection.[24]: 143 [30] By 1613 one conservator estimated the library's collection at 32,000 volumes.[30]

A document from the Qarawiyyin's library which is claimed by some scholars to be the world's oldest surviving medical degree, issued in 1207 CE

A document from the Qarawiyyin's library which is claimed by some scholars to be the world's oldest surviving medical degree, issued in 1207 CEStudents were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (riwaq) overlooking the scholars' circle".[15] The 12th-century cartographer Mohammed al-Idrisi, whose maps aided European exploration during the Renaissance, is said to have lived in Fez for some time, suggesting that he may have worked or studied at al-Qarawiyyin. The institution has produced numerous scholars who have strongly influenced the intellectual and academic history of the Muslim world. Among them are Ibn Rushayd al-Sabti (d. 1321), Mohammed Ibn al-Hajj al-Abdari al-Fasi (d. 1336), Abu Imran al-Fasi (d. 1015) – a leading theorist of the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, and Leo Africanus. Pioneer scholars such as Muhammad al-Idrissi (d.1166 AD), Ibn al-Arabi (1165–1240 AD), Ibn Khaldun (1332–1395 AD), Ibn al-Khatib (d. 1374), Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji (Alpetragius) (d. 1294), and Ali ibn Hirzihim (d. 1163) were all connected with al-Qarawiyyin as either students or lecturers.[31] Some Christian scholars visited al-Qarawiyyin, including Nicolas Cleynaerts (d. 1542)[35][24]: 252 and the Jacobus Golius (d. 1667).[31] The 19th-century orientalist Jousé Ponteleimon Krestovitich also claimed that Gerbert d'Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II) studied at al-Qarawiyyin in the 10th century.[36][24]: 138 Although this claim about Gerbert is sometimes repeated by modern authors,[6][37] modern scholarship has not produced evidence to support this story.[38][39]

Decline and reformsAl-Qarawiyyin underwent a general decline in later centuries along with Fez. The strength of its teaching stagnated and its curriculum decreased in range and scope, becoming focused on traditional Islamic sciences and Arabic linguistic studies. Even some traditional Islamic specializations like tafsir (Quranic exegesis) were progressively neglected or abandoned.[16][20] In 1788–89, the 'Alawi sultan Muhammad ibn Abdallah introduced reforms that regulated the institution's program, but also imposed stricter limits and excluded logic, philosophy, and the more radical Sufi texts from the curriculum.[15][20][40] Other subjects also disappeared over time, such as astronomy and medicine.[20] In 1845 Sultan Abd al-Rahman carried out further reforms, but it is unclear if this had any significant long-term effects.[16][20] Between 1830 and 1906 the number of faculty decreased from 425 to 266 (of which, among the latter, only 101 were still teaching).[16]: 71

By the 19th century, the mosque's library also suffered from decline and neglect.[20][30] A significant portion of its collection was lost over time, most likely due to lax supervision and to books that were not returned.[9]: 472 By the beginning of the 20th century, the collection had been reduced to around 1,600 manuscripts and 400 printed books, though many valuable historic items were retained.[20]

By the late 19th century, Western scholars began to recognize al-Qarawiyyin as a "university", a description which would become more established during the French protectorate period in the 20th century.[13]

20th century and transformation into state university View of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in 1916

View of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in 1916At the time Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, al-Qarawiyyin worsened as a religious center of learning from its medieval prime,[16] though it retained some significance as an educational venue for the sultan's administration.[16] The student body was rigidly divided along social strata: ethnicity (Arab or Berber), social status, personal wealth, and geographic background (rural or urban) determined the group membership of the students who were segregated by the teaching facility, as well as in their personal quarters.[16]

The French administration implemented a number of structural reforms between 1914 and 1947, including the institution of calendars, appointment of teachers, salaries, schedules, general administration, and the replacement of the ijazah with the shahada alamiyha, but did not modernize the contents of teaching likewise which were still dominated by the traditional worldviews of the ulama.[16] At the same time, the student numbers at al-Qarawiyyin decreased to 300 in 1922 as the Moroccan elite sent their children to the newly founded Western-style colleges and institutes elsewhere in the country.[16] Moroccan and French authorities began planning further reforms for al-Qarawiyyin in 1929.[13] In 1931 and 1933, on the orders of Muhammad V, the institution's teaching was reorganized into elementary, secondary, and higher education.[20][15][40]

Al-Qarawiyyin also played a role in the Moroccan nationalist movement and in protests against the French colonial regime. Many Moroccan nationalists had received their education here and some of their informal political networks were established due to the shared educational background.[41]: 140, 146 In July 1930, al-Qarawiyyin strongly participated in the propagation of Ya Latif, a communal prayer recited in times of calamity, to raise awareness and opposition to the Berber Dahir decreed by the French authorities two months earlier.[42][41]: 143–144 In 1937 the mosque was one of the rallying points (along with the nearby R'cif mosque) for demonstrations in response to a violent crackdown on Moroccan protesters in Meknes, which ended with French troops being deployed across Fes el-Bali and at the mosques.[1]: 387–389 [41]: 168

The main entrance to the library and other southern annexes of the mosque today, off Place Seffarine

The main entrance to the library and other southern annexes of the mosque today, off Place SeffarineIn 1947, al-Qarawiyyin was integrated into the state educational system,[43] and women were first admitted to study there during the 1940s.[44] In 1963, after Moroccan independence, al-Qarawiyyin was officially transformed by royal decree into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education.[16][45][46] Classes at the old mosque ceased and a new campus was established at a former French Army barracks.[16] While the dean took his seat at Fez, four faculties were founded in and outside the city: a faculty of Islamic law in Fez, a faculty of Arab studies in Marrakech, and two faculties of theology in Tétouan and near Agadir. Modern curricula and textbooks were introduced and the professional training of the teachers improved.[16][47] Following the reforms, al-Qarawiyyin was officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" in 1965.[16]

In 1975, General Studies was transferred to the newly founded Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University; al-Qarawiyyin kept the Islamic and theological courses of studies.[citation needed] In 1973, Abdelhadi Tazi published a three-volume history of the establishment entitled جامع القرويين (The al-Qarawiyyin Mosque).[48]

In 1988, after a hiatus of almost three decades, the teaching of traditional Islamic education at al-Qarawiyyin was resumed by King Hassan II in what has been interpreted as a move to bolster conservative support for the monarchy.[16]

The Adjustments of Original Institutions of the Higher Learning: the Madrasah. Significantly, the institutional adjustments of the madrasahs affected both the structure and the content of these institutions. In terms of structure, the adjustments were twofold: the reorganization of the available original madaris and the creation of new institutions. This resulted in two different types of Islamic teaching institutions in al-Maghrib. The first type was derived from the fusion of old madaris with new universities. For example, Morocco transformed Al-Qarawiyin (859 A.D.) into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education in 1963.

^ Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: Historical Dictionary of Morocco, 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8108-5341-6, p. 348al-qarawiyin is the oldest university in Morocco. It was founded as a mosque in Fès in the middle of the ninth century. It has been a destination for students and scholars of Islamic sciences and Arabic studies throughout the history of Morocco. There were also other religious schools like the madras of ibn yusuf and other schools in the sus. This system of basic education called al-ta'lim al-aSil was funded by the sultans of Morocco and many famous traditional families. After independence, al-qarawiyin maintained its reputation, but it seemed important to transform it into a university that would prepare graduates for a modern country while maintaining an emphasis on Islamic studies. Hence, al-qarawiyin university was founded in February 1963 and, while the dean's residence was kept in Fès, the new university initially had four colleges located in major regions of the country known for their religious influences and madrasas. These colleges were kuliyat al-shari's in Fès, kuliyat uSul al-din in Tétouan, kuliyat al-lugha al-'arabiya in Marrakech (all founded in 1963), and kuliyat al-shari'a in Ait Melloul near Agadir, which was founded in 1979.

^ Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: Historical Dictionary of Morocco, 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8108-5341-6, p. 348 ^ Tazi, Abdelhadi (2000). جامع القرويين [The al-Qarawiyyin Mosque] (in Arabic). ISBN 9981-808-43-1.

Add new comment