Saudi Arabia

Context of Saudi Arabia

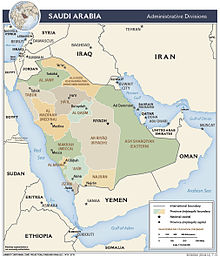

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about 2,150,000 km2 (830,000 sq mi), making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the Arab world, and the largest in Western Asia and the Middle East. It is bordered by the Red Sea to the west; Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the north; the Persian Gulf, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to the east; Oman to the southeast; and Yemen to the south. Bahrain is an island country off its east coast. The Gulf of Aqaba in the northwest separates Saudi Arabia from Egypt and Israel. Saudi Arabia is the only country with a coastline along both the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, and most of its terrain consists of arid desert, lowland, steppe, and mountains. Its capital and largest city is Riyadh. The country is home to Mecca and Medina, the two holiest cities in I...Read more

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about 2,150,000 km2 (830,000 sq mi), making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the Arab world, and the largest in Western Asia and the Middle East. It is bordered by the Red Sea to the west; Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the north; the Persian Gulf, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to the east; Oman to the southeast; and Yemen to the south. Bahrain is an island country off its east coast. The Gulf of Aqaba in the northwest separates Saudi Arabia from Egypt and Israel. Saudi Arabia is the only country with a coastline along both the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, and most of its terrain consists of arid desert, lowland, steppe, and mountains. Its capital and largest city is Riyadh. The country is home to Mecca and Medina, the two holiest cities in Islam.

Pre-Islamic Arabia, the territory that constitutes modern-day Saudi Arabia, was the site of several ancient cultures and civilizations; the prehistory of Saudi Arabia shows some of the earliest traces of human activity in the world. The world's second-largest religion, Islam, emerged in what is now Saudi Arabia. In the early 7th century, the Islamic prophet Muhammad united the population of the Arabian Peninsula and created a single Islamic religious polity. Following his death in 632, his followers rapidly expanded the territory under Muslim rule beyond Arabia, conquering huge and unprecedented swathes of territory (from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to parts of Central and South Asia in the east) in a matter of decades. Arab dynasties originating from modern-day Saudi Arabia founded the Rashidun (632–661), Umayyad (661–750), Abbasid (750–1517), and Fatimid (909–1171) caliphates, as well as numerous other dynasties in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

The area of modern-day Saudi Arabia formerly consisted of mainly four distinct historical regions: Hejaz, Najd, and parts of Eastern Arabia (Al-Ahsa) and South Arabia ('Asir). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was founded in 1932 by King Abdulaziz (known as Ibn Saud in the West). He united the four regions into a single state through a series of conquests beginning in 1902 with the capture of Riyadh, the ancestral home of his family, the House of Saud. Saudi Arabia has since been an absolute monarchy, where political decisions are made on the basis of consultation among the King, the Council of Ministers, and the country’s traditional elites that oversee a highly authoritarian regime. The ultraconservative Wahhabi religious movement within Sunni Islam was described as a "predominant feature of Saudi culture" until the 2000s. In 2016, the Saudi Arabian government made moves that curtailed the influence of religious establishment and restricted the activities of the morality police, launched economic programme of Saudi Vision 2030 in an attempt to enhance and revive social development and build a more robust and effective society. In its Basic Law, Saudi Arabia continues to define itself as a sovereign Arab Islamic state with Islam as its official religion, Arabic as its official language, and Riyadh as its capital.

Petroleum was discovered in 1938 and followed up by several other finds in the Eastern Province. Saudi Arabia has since become the world's second-largest oil producer (behind the US) and the world's largest oil exporter, controlling the world's second-largest oil reserves and the fourth-largest gas reserves. The kingdom is categorized as a World Bank high-income economy and is the only Arab country to be part of the G20 major economies. The state has attracted criticism for a variety of reasons, including its role in the Yemeni Civil War, alleged sponsorship of Islamic terrorism and its poor human rights record, including the excessive and often extrajudicial use of capital punishment.

Saudi Arabia is considered both a regional and middle power. The Saudi economy is the largest in the Middle East; the world's eighteenth-largest economy by nominal GDP and the seventeenth-largest by PPP. As a country with a very high Human Development Index, it offers a tuition-free university education, no personal income tax, and a free universal health care system. Saudi Arabia is home to the world's third-largest immigrant population. It also has one of the world's youngest populations, with approximately 50 per cent of its population of 34.2 million being under 25 years old. In addition to being a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council, Saudi Arabia is an active and founding member of the United Nations, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, Arab League, Arab Air Carriers Organization and OPEC.

More about Saudi Arabia

- Currency Saudi riyal

- Calling code +966

- Internet domain .sa

- Mains voltage 230V/60Hz

- Democracy index 2.08

- Population 791105

- Area 2250000

- Driving side right

- Prehistory

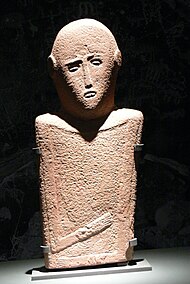

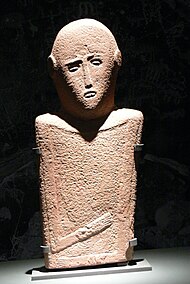

Anthropomorphic stela (4th millennium BC), sandstone, 57x27 cm, from El-Maakir-Qaryat al-Kaafa (National Museum of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh)

Anthropomorphic stela (4th millennium BC), sandstone, 57x27 cm, from El-Maakir-Qaryat al-Kaafa (National Museum of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh)There is evidence that human habitation in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to about 125,000 years ago.[1] A 2011 study found that the first modern humans to spread east across Asia left Africa about 75,000 years ago across the Bab-el-Mandeb connecting the Horn of Africa and Arabia.[2] The Arabian peninsula is regarded as a central figure in the understanding of hominin evolution and...Read more

PrehistoryRead less Anthropomorphic stela (4th millennium BC), sandstone, 57x27 cm, from El-Maakir-Qaryat al-Kaafa (National Museum of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh)

Anthropomorphic stela (4th millennium BC), sandstone, 57x27 cm, from El-Maakir-Qaryat al-Kaafa (National Museum of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh)There is evidence that human habitation in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to about 125,000 years ago.[1] A 2011 study found that the first modern humans to spread east across Asia left Africa about 75,000 years ago across the Bab-el-Mandeb connecting the Horn of Africa and Arabia.[2] The Arabian peninsula is regarded as a central figure in the understanding of hominin evolution and dispersals. Arabia underwent an extreme environmental fluctuation in the Quaternary that led to profound evolutionary and demographic changes. Arabia has a rich Lower Paleolithic record, and the quantity of Oldowan-like sites in the region indicate a significant role that Arabia had played in the early hominin colonization of Eurasia.[3]

In the Neolithic period, prominent cultures such as Al-Magar, whose centre lay in modern-day southwestern Najd flourished. Al-Magar could be considered a "Neolithic Revolution" in human knowledge and handicraft skills.[4] The culture is characterized as being one of the world's first to involve the widespread domestication of animals, particularly the horse, during the Neolithic period.[5][6] Aside from horses, animals such as sheep, goats, dogs, in particular of the Saluki breed, ostriches, falcons and fish were discovered in the form of stone statues and rock engravings. Al-Magar statues were made from local stone, and it seems that the statues were fixed in a central building that might have had a significant role in the social and religious life of the inhabitants.[7]

In November 2017, hunting scenes showing images of the most likely domesticated dogs, resembling the Canaan dog, wearing leashes were discovered in Shuwaymis, a hilly region of northwestern Saudi Arabia. These rock engravings date back more than 8,000 years, making them the earliest depictions of dogs in the world.[8]

At the end of the 4th millennium BC, Arabia entered the Bronze Age after witnessing drastic transformations; metals were widely used, and the period was characterized by its 2 m high burials which were simultaneously followed by the existence of numerous temples, that included many free-standing sculptures originally painted with red colours.[9]

In May 2021, archaeologists announced that a 350,000-year-old Acheulean site named An Nasim in the Hail region could be the oldest human habitation site in northern Saudi Arabia. The site was first discovered in 2015 using remote sensing and palaeohydrological modelling. It contains paleolake deposits related with Middle Pleistocene materials. 354 artefacts, hand axes and stone tools, flakes discovered by researchers provided information about tool-making traditions of the earliest living man inhabited South-West Asia. Besides, Paleolithic artefacts are similar to material remains uncovered at the Acheulean sites in the Nefud Desert.[10][11][12][13]

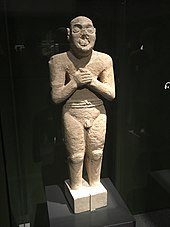

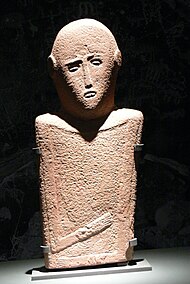

Pre-Islamic The "Worshipping Servant" statue (2500 BC), above one metre (3 ft 3 in) in height, is much taller than any possible Mesopotamian or Harappan models. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.[14]

The "Worshipping Servant" statue (2500 BC), above one metre (3 ft 3 in) in height, is much taller than any possible Mesopotamian or Harappan models. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.[14]The earliest sedentary culture in Saudi Arabia dates back to the Ubaid period, upon discovering various pottery sherds at Dosariyah. Initial analysis of the discovery concluded that the eastern province of Saudi Arabia was the homeland of the earliest settlers of Mesopotamia, and by extension, the likely origin of the Sumerians. However, experts such as Joan Oates had the opportunity to see the Ubaid period sherds in eastern Arabia and consequently conclude that the sherds date to the last two phases of the Ubaid period (period three and four), while a handful of examples could be classified roughly as either Ubaid 3 or Ubaid 2. Thus, the idea that colonists from Saudi Arabia had emigrated to southern Mesopotamia and founded the region's first sedentary culture was abandoned.[15]

Climatic change and the onset of aridity may have brought about the end of this phase of settlement, as little archaeological evidence exists from the succeeding millennium.[16] The settlement of the region picks up again in the period of Dilmun in the early 3rd millennium. Known records from Uruk refer to a place called Dilmun, associated on several occasions with copper, and in later periods it was a source of imported woods in southern Mesopotamia. A number of scholars have suggested that Dilmun originally designated the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, notably linked with the major Dilmunite settlements of Umm an-Nussi and Umm ar-Ramadh in the interior and Tarout on the coast. It is likely that Tarout Island was the main port and the capital of Dilmun.[14] Mesopotamian inscribed clay tablets suggests that, in the early period of Dilmun, a form of hierarchical organized political structure existed. In 1966, an earthwork in Tarout exposed an ancient burial field that yielded a large, impressive statue dating to the Dilmunite period (mid 3rd millennium BC). The statue was locally made under the strong Mesopotamian influence on the artistic principle of Dilmun.[14]

By 2200 BC, the centre of Dilmun shifted for unknown reasons from Tarout and the Saudi Arabian mainland to the island of Bahrain, and a highly developed settlement emerged there, where a laborious temple complex and thousands of burial mounds dating to this period were discovered.[14]

Qaṣr Al-Farīd, the largest of the 131 rock-cut monumental tombs built from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, with their elaborately ornamented façades, at the extensive ancient Nabatean archaeological site of Hegra located in the area of Al-'Ula within Al Madinah Region in the Hejaz. A UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2008.By the late Bronze Age, a historically recorded people and land (Midian and the Midianites) in the north-western portion of Saudi Arabia are well-documented in the Bible. Centred in Tabouk, it stretched from Wadi Arabah in the north to the area of al-Wejh in the south.[17] The capital of Midian was Qurayyah,[18] it consists of a large fortified citadel encompassing 35 hectares and below it lies a walled settlement of 15 hectares. The city hosted as many as 10 to 12 thousand inhabitants.[19] The Midianites were depicted in two major events in the Bible that recount Israel's two wars with Midian, somewhere in the early 11th century BC. Politically, the Midianites were described as having a decentralized structure headed by five kings (Evi, Rekem, Tsur, Hur, and Reba), the names appears to be toponyms of important Midianite settlements.[20] It is common to view that Midian designated a confederation of tribes, the sedentary element settled in the Hijaz while its nomadic affiliates pastured, and sometimes pillaged as far away land as Palestine.[21] The nomadic Midianites were one of the earliest exploiters of the domestication of camels that enabled them to navigate through the harsh terrains of the region.[21]

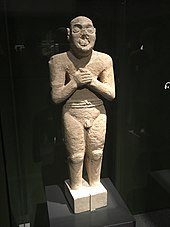

Colossal statue from Al-'Ula in the Hejaz (6th–4th century BC), it followed the standardized artistic sculpting of the Lihyanite kingdom. The original statue was painted with white. (Louvre Museum, Paris)[22]

Colossal statue from Al-'Ula in the Hejaz (6th–4th century BC), it followed the standardized artistic sculpting of the Lihyanite kingdom. The original statue was painted with white. (Louvre Museum, Paris)[22]At the end of the 7th century BC, an emerging kingdom appeared in the historical theatre of north-western Arabia. It started as a Sheikdom of Dedan, which developed into the Kingdom of Lihyan tribe.[23] The earliest attestation of state regality, King of Lihyan, was in the mid-sixth century BC.[24] The second stage of the kingdom saw the transformation of Dedan from a mere city-state of which only influence they exerted was inside their city walls, to a kingdom that encompasses much wider domain that marked the pinnacle of Lihyan civilization.[23] The third state occurred during the early 3rd century BC with bursting economic activity between the south and north that made Lihyan acquire large influence suitable to its strategic position on the caravan road.[25]

Lihyan was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arabian kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula.[26] The Lihyanites ruled over a large domain from Yathrib in the south and parts of the Levant in the north.[27] In antiquity, Gulf of Aqaba used to be called Gulf of Lihyan. A testimony to the extensive influence that Lihyan acquired.[28]

The Lihyanites fell into the hands of the Nabataeans around 65 BC upon their seizure of Hegra then marching to Tayma, and to their capital Dedan in 9 BC. The Nabataeans ruled large portions of north Arabia until their domain was annexed by the Roman Empire, which renamed it Arabia Petraea, and remained under the rule of the Romans until 630.[29]

Middle Ages and rise of Islam At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) covered 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi)[30] and 62 million people (29 per cent of the world's population),[31] making it one of the largest empires in history in both area and proportion of the world's population. It was also larger than any previous empire in history.

At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) covered 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi)[30] and 62 million people (29 per cent of the world's population),[31] making it one of the largest empires in history in both area and proportion of the world's population. It was also larger than any previous empire in history.Shortly before the advent of Islam, apart from urban trading settlements (such as Mecca and Medina), much of what was to become Saudi Arabia was populated by nomadic pastoral tribal societies.[32] The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born in Mecca in about 570 CE. In the early 7th century, Muhammad united the various tribes of the peninsula and created a single Islamic religious polity.[33] Following his death in 632, his followers rapidly expanded the territory under Muslim rule beyond Arabia, conquering huge and unprecedented swathes of territory (from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to parts of Central and South Asia in the east) in a matter of decades. Arabia soon became a more politically peripheral region of the Muslim world as the focus shifted to the vast and newly conquered lands.[33]

Arabs originating from modern-day Saudi Arabia, the Hejaz in particular, founded the Rashidun (632–661), Umayyad (661–750), Abbasid (750–1517), and the Fatimid (909–1171) caliphates. From the 10th century to the early 20th century, Mecca and Medina were under the control of a local Arab ruler known as the Sharif of Mecca, but at most times the Sharif owed allegiance to the ruler of one of the major Islamic empires based in Baghdad, Cairo or Istanbul. Most of the remainder of what became Saudi Arabia reverted to traditional tribal rule.[34][35]

The Battle of Badr, 13 March 624 CE

The Battle of Badr, 13 March 624 CEFor much of the 10th century, the Isma'ili-Shi'ite Qarmatians were the most powerful force in the Persian Gulf. In 930, the Qarmatians pillaged Mecca, outraging the Muslim world, particularly with their theft of the Black Stone.[36] In 1077–1078, an Arab Sheikh named Abdullah bin Ali Al Uyuni defeated the Qarmatians in Bahrain and al-Hasa with the help of the Great Seljuq Empire and founded the Uyunid dynasty.[37][38] The Uyunid Emirate later underwent expansion with its territory stretching from Najd to the Syrian desert.[39] They were overthrown by the Usfurids in 1253.[40] Usfurid rule was weakened after Persian rulers of Hormuz captured Bahrain and Qatif in 1320.[41] The vassals of Ormuz, the Shia Jarwanid dynasty came to rule eastern Arabia in the 14th century.[42][43] The Jabrids took control of the region after overthrowing the Jarwanids in the 15th century and clashed with Hormuz for more than two decades over the region for its economic revenues, until finally agreeing to pay tribute in 1507.[42] Al-Muntafiq tribe later took over the region and came under Ottoman suzerainty. The Bani Khalid tribe later revolted against them in the 17th century and took control.[44] Their rule extended from Iraq to Oman at its height and they too came under Ottoman suzerainty.[45][46]

Ottoman HejazIn the 16th century, the Ottomans added the Red Sea and Persian Gulf coast (the Hejaz, Asir and Al-Ahsa) to the Empire and claimed suzerainty over the interior. One reason was to thwart Portuguese attempts to attack the Red Sea (hence the Hejaz) and the Indian Ocean.[47] The Ottoman degree of control over these lands varied over the next four centuries with the fluctuating strength or weakness of the Empire's central authority.[48][49] These changes contributed to later uncertainties, such as the dispute with Transjordan over the inclusion of the sanjak of Ma'an, including the cities of Ma'an and Aqaba.[citation needed]

Foundation of the Saud dynasty Atlas map of Arabia and the wider region in 1883

Atlas map of Arabia and the wider region in 1883The emergence of what was to become the Saudi royal family, known as the Al Saud, began in Nejd in central Arabia in February 1727,[50][51] when Muhammad bin Saud, founder of the dynasty, joined forces with the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab,[52] founder of the Wahhabi movement, a strict puritanical form of Sunni Islam.[53] This alliance formed in the 18th century provided the ideological impetus to Saudi expansion and remains the basis of Saudi Arabian dynastic rule today.[54]

In 1727, the Emirate of Diriyah established in the area around Riyadh rapidly expanded and briefly controlled most of the present-day territory of Saudi Arabia,[55] sacking Karbala in 1802, and capturing Mecca in 1803. In 1818, it was destroyed by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali Pasha.[56] The much smaller Emirate of Nejd was established in 1824. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Al Saud contested control of the interior of what was to become Saudi Arabia with another Arabian ruling family, the Al Rashid, who ruled the Emirate of Jabal Shammar. By 1891, the Al Rashid were victorious and the Al Saud were driven into exile in Kuwait.[34]

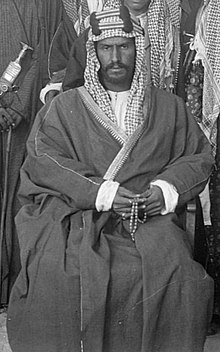

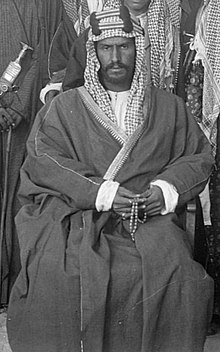

Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, the founding father and first king of Saudi Arabia

Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, the founding father and first king of Saudi ArabiaAt the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire continued to control or have a suzerainty over most of the peninsula. Subject to this suzerainty, Arabia was ruled by a patchwork of tribal rulers,[57][58] with the Sharif of Mecca having pre-eminence and ruling the Hejaz.[59] In 1902, Abdul Rahman's son, Abdul Aziz—later to be known as Ibn Saud—recaptured control of Riyadh bringing the Al Saud back to Nejd, creating the third "Saudi state".[34] Ibn Saud gained the support of the Ikhwan, a tribal army inspired by Wahhabism and led by Faisal Al-Dawish, and which had grown quickly after its foundation in 1912.[60] With the aid of the Ikhwan, Ibn Saud captured Al-Ahsa from the Ottomans in 1913.

In 1916, with the encouragement and support of Britain (which was fighting the Ottomans in World War I), the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, led a pan-Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire to create a united Arab state.[61] Although the Arab Revolt of 1916 to 1918 failed in its objective, the Allied victory in World War I resulted in the end of Ottoman suzerainty and control in Arabia and Hussein bin Ali became King of Hejaz.[62]

Ibn Saud avoided involvement in the Arab Revolt, and instead continued his struggle with the Al Rashid. Following the latter's final defeat, he took the title Sultan of Nejd in 1921. With the help of the Ikhwan, the Kingdom of Hejaz was conquered in 1924–25, and on 10 January 1926, Ibn Saud declared himself King of Hejaz.[63] For the next five years, he administered the two parts of his dual kingdom as separate units.[34]

After the conquest of the Hejaz, the Ikhwan leadership's objective switched to expansion of the Wahhabist realm into the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait, and began raiding those territories. This met with Ibn Saud's opposition, as he recognized the danger of a direct conflict with the British. At the same time, the Ikhwan became disenchanted with Ibn Saud's domestic policies which appeared to favour modernization and the increase in the number of non-Muslim foreigners in the country. As a result, they turned against Ibn Saud and, after a two-year struggle, were defeated in 1929 at the Battle of Sabilla, where their leaders were massacred.[64] On 23 September 1932, the two kingdoms of the Hejaz and Nejd were united as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,[34] and that date is now a national holiday called Saudi National Day.[65]

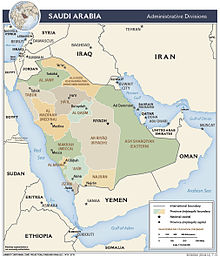

Post-unification Political map of Saudi Arabia

Political map of Saudi ArabiaThe new kingdom was reliant on limited agriculture and pilgrimage revenues.[66] In 1938, vast reserves of oil were discovered in the Al-Ahsa region along the coast of the Persian Gulf, and full-scale development of the oil fields began in 1941 under the US-controlled Aramco (Arabian American Oil Company). Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and substantial political leverage internationally.[34]

Cultural life rapidly developed, primarily in the Hejaz, which was the centre for newspapers and radio. However, the large influx of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia in the oil industry increased the pre-existing propensity for xenophobia. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and extravagant. By the 1950s this had led to large governmental deficits and excessive foreign borrowing.[34]

In 1953, Saud of Saudi Arabia succeeded as the king of Saudi Arabia, on his father's death, until 1964 when he was deposed in favour of his half brother Faisal of Saudi Arabia, after an intense rivalry, fuelled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. In 1972, Saudi Arabia gained a 20 per cent control in Aramco, thereby decreasing US control over Saudi oil.[citation needed]

In 1973, Saudi Arabia led an oil boycott against the Western countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War against Egypt and Syria, leading to the quadrupling of oil prices.[34] In 1975, Faisal was assassinated by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid and was succeeded by his half-brother King Khalid.[67]

By 1976, Saudi Arabia had become the largest oil producer in the world.[68] Khalid's reign saw economic and social development progress at an extremely rapid rate, transforming the infrastructure and educational system of the country;[34] in foreign policy, close ties with the US were developed.[67] In 1979, two events occurred which greatly concerned the government,[69] and had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy. The first was the Iranian Islamic Revolution. It was feared that the country's Shi'ite minority in the Eastern Province (which is also the location of the oil fields) might rebel under the influence of their Iranian co-religionists. There were several anti-government uprisings in the region such as the 1979 Qatif Uprising.[70]

The second event was the Grand Mosque Seizure in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi government.[70] The government regained control of the mosque after 10 days and those captured were executed. Part of the response of the royal family was to enforce the much stricter observance of traditional religious and social norms in the country (for example, the closure of cinemas) and to give the Ulema a greater role in government.[71] Neither entirely succeeded as Islamism continued to grow in strength.[72]

Map of Saudi Arabian administrative regions and roadways

Map of Saudi Arabian administrative regions and roadwaysIn 1980, Saudi Arabia bought out the American interests in Aramco.[73] King Khalid died of a heart attack in June 1982. He was succeeded by his brother, King Fahd, who added the title "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" to his name in 1986 in response to considerable fundamentalist pressure to avoid the use of "majesty" in association with anything except God. Fahd continued to develop close relations with the United States and increased the purchase of American and British military equipment.[34]

The vast wealth generated by oil revenues was beginning to have an even greater impact on Saudi society. It led to rapid technological (but not cultural) modernization, urbanization, mass public education, and the creation of new media. This and the presence of increasingly large numbers of foreign workers greatly affected traditional Saudi norms and values. Although there was a dramatic change in the social and economic life of the country, political power continued to be monopolized by the royal family[34] leading to discontent among many Saudis who began to look for wider participation in government.[74]

In the 1980s, Saudi Arabia spent $25 billion in support of Saddam Hussein in the Iran–Iraq War;[75] however, Saudi Arabia condemned the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and asked the US to intervene.[34] King Fahd allowed American and coalition troops to be stationed in Saudi Arabia. He invited the Kuwaiti government and many of its citizens to stay in Saudi Arabia, but expelled citizens of Yemen and Jordan because of their governments' support of Iraq. In 1991, Saudi Arabian forces were involved both in bombing raids on Iraq and in the land invasion that helped to liberate Kuwait.[citation needed]

Saudi Arabia's relations with the West began to cause growing concern among some of the ulema and students of Sharia law and was one of the issues that led to an increase in Islamist terrorism in Saudi Arabia, as well as Islamist terrorist attacks in Western countries by Saudi nationals. Osama bin Laden was a Saudi citizen (until stripped of his citizenship in 1994) and was responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in East Africa and the 2000 USS Cole bombing near the port of Aden, Yemen. 15 of the 19 terrorists involved in September 11 attacks in New York City, Washington, D.C., and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania were Saudi nationals.[76] Many Saudis who did not support the Islamist terrorists were nevertheless deeply unhappy with the government's policies.[77]

Islamism was not the only source of hostility to the government. Although extremely wealthy by the 21st century, Saudi Arabia's economy was near stagnant. High taxes and a growth in unemployment have contributed to discontent and have been reflected in a rise in civil unrest, and discontent with the royal family. In response, a number of limited reforms were initiated by King Fahd. In March 1992, he introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasized the duties and responsibilities of a ruler. In December 1993, the Consultative Council was inaugurated. It is composed of a chairman and 60 members—all chosen by the King. The King's intent was to respond to dissent while making as few actual changes in the status quo as possible.[citation needed] Fahd made it clear that he did not have democracy in mind, saying: "A system based on elections is not consistent with our Islamic creed, which [approves of] government by consultation [shūrā]."[34]

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke, and the Crown Prince, Abdullah, assumed the role of de facto regent, taking on the day-to-day running of the country; however, his authority was hindered by conflict with Fahd's full brothers (known, with Fahd, as the "Sudairi Seven").[78] From the 1990s, signs of discontent continued and included, in 2003 and 2004, a series of bombings and armed violence in Riyadh, Jeddah, Yanbu and Khobar.[79] In February–April 2005, the first-ever nationwide municipal elections were held in Saudi Arabia. Women were not allowed to take part in the poll.[34]

Map of oil and gas pipelines in the Middle-East

Map of oil and gas pipelines in the Middle-EastIn 2005, King Fahd died and was succeeded by Abdullah, who continued the policy of minimum reform and clamping down on protests. The king introduced a number of economic reforms aimed at reducing the country's reliance on oil revenue: limited deregulation, encouragement of foreign investment, and privatization. In February 2009, Abdullah announced a series of governmental changes to the judiciary, armed forces, and various ministries to modernize these institutions including the replacement of senior appointees in the judiciary and the Mutaween (religious police) with more moderate individuals and the appointment of the country's first female deputy minister.[34]

On 29 January 2011, hundreds of protesters gathered in the city of Jeddah in a rare display of criticism against the city's poor infrastructure after deadly floods swept through the city, killing 11 people.[80] Police stopped the demonstration after about 15 minutes and arrested 30 to 50 people.[81]

Since 2011, Saudi Arabia has been affected by its own Arab Spring protests.[82] In response, King Abdullah announced on 22 February 2011 a series of benefits for citizens amounting to $36 billion, of which $10.7 billion was earmarked for housing.[83][84][85] No political reforms were announced as part of the package, though some prisoners indicted for financial crimes were pardoned.[86] On 18 March the same year, King Abdullah announced a package of $93 billion, which included 500,000 new homes to a cost of $67 billion, in addition to creating 60,000 new security jobs.[87][88] Although male-only municipal elections were held on 29 September 2011,[89][90] Abdullah allowed women to vote and be elected in the 2015 municipal elections, and also to be nominated to the Shura Council.[91]

Since 2001, Saudi Arabia has engaged in widespread internet censorship. Most online censorship generally falls into two categories: one based on censoring "immoral" (mostly pornographic and LGBT-supportive websites along with websites promoting any religious ideology other than Sunni Islam) and one based on a blacklist run by Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Media, which primarily censors websites critical of the Saudi regime or associated with parties that are opposed to or opposed by Saudi Arabia.[92][93][94]

^ Callaway, Ewen (27 January 2011). "Early human migration written in stone tools : Nature News". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.55. ^ Armitage, S. J.; Jasim, S. A.; Marks, A. E.; Parker, A. G.; Usik, V. I.; Uerpmann, H.-P. (2011). "Hints Of Earlier Human Exit From Africa". Science. Science News. 331 (6016): 453–456. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486. S2CID 20296624. ^ Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. New York: Springer. pp. 27–46.[ISBN missing] ^ "Al Magar – Paleolithic & Neolithic History". paleolithic-neolithic.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2018. ^ Sylvia, Smith (26 February 2013). "Desert finds challenge horse taming ideas". BCC. Retrieved 13 November 2016. ^ John, Henzell (11 March 2013). "Carved in stone: were the Arabs the first to tame the horse?". thenational. thenational. Retrieved 12 November 2016. ^ "Discovery points to roots of arabian breed – Features". Horsetalk.co.nz. 27 August 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2022. ^ Grimm, David (16 November 2017). "These may be the world's first images of dogsand they're wearing leashes". Science Magazine. Retrieved 18 June 2018. ^ طرق التجارة القديمة، روائع آثار المملكة العربية السعودية pp. 156–157 ^ Scerri, Eleanor M. L.; Frouin, Marine; Breeze, Paul S.; Armitage, Simon J.; Candy, Ian; Groucutt, Huw S.; Drake, Nick; Parton, Ash; White, Tom S.; Alsharekh, Abdullah M.; Petraglia, Michael D. (12 May 2021). "The expansion of Acheulean hominins into the Nefud Desert of Arabia". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 10111. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1110111S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-89489-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8115331. PMID 33980918. ^ "Saudi Arabia discovers new archaeological site dating back to 350,000 years". Saudigazette. 12 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021. ^ "Saudi Arabia discovers a 350,000-year-old archaeological site in Hail". The National. 13 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021. ^ "Ancient site in Nefud Desert offers glimpse of early human activity in Saudi Arabia". Arab News. Retrieved 17 May 2021. ^ a b c d Roads of Arabia p. 180 ^ Roads of Arabia p. 175. ^ Roads of Arabia p. 176. ^ Koenig 1971; Payne 1983: Briggs 2009 ^ The World around the Old Testament: The People and Places of the Ancient Near East. Baker Publishing Group; 2016. ISBN 978-1-4934-0574-9 p. 462. ^ Michael D. Coogan. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press; 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-988148-2. p. 110. ^ Knauf, 1988 ^ a b Midian, Moab and Edom: The History and Archaeology of Late Bronze and Iron Age Jordan and North-West Arabia p. 163. ^ Farag, Mona (7 September 2022). "Louvre Museum in Paris to display Saudi Arabia's ancient AlUla statue". The National. Retrieved 24 September 2022. ^ a b The State of Lihyan: A New Perspective – p. 192 ^ J. Schiettecatte: The political map of Arabia and the Middle East in the third century AD revealed by a Sabaean inscription – p. 183 ^ The State of Lihyan: A New Perspective ^ Rohmer, J. & Charloux, G. (2015), "From Liyan to the Nabataeans: Dating the End of the Iron Age in Northwestern Arabia" – p. 297 ^ "Lion Tombs of Dedan". Saudi Arabia Tourism Guide. 19 September 2017. ^ Discovering Lehi. Cedar Fort; 1996. ISBN 978-1-4621-2638-5. p. 153. ^ Taylor, Jane (2005). Petra. London: Aurum Press Ltd. pp. 25–31. ISBN 9957-451-04-9. ^ Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 475–504. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. ^ Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994), The End of the Jihad State, the Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd-al Malik and the collapse of the Umayyads, State University of New York Press, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7 ^ Gordon, Matthew (2005). The Rise of Islam. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-313-32522-9. ^ a b Cite error: The named reference James E. Lindsay 2005 33 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "History of Arabia". Encyclopædia Britannica. ^ William Gordon East (1971). The changing map of Asia. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-416-16850-1. ^ Glassé, Cyril (2008). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Walnut Creek CA: AltaMira Press p. 369 ^ Commins, David (2012). The Gulf States: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84885-278-5. ^ C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 94–95. ^ Khulusi, Safa (1975). "A Thirteenth Century Poet from Bahrain". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 6: 91–102. JSTOR 41223173. (registration required) ^ Joseph Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization, Taylor and Francis, 2006, p. 95 ^ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984 pp66-8 ^ a b Juan Ricardo Cole (2002). Sacred space and holy war: the politics, culture and history of Shi'ite Islam. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-86064-736-9. Retrieved 27 September 2017. ^ "Arabia". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. ^ Zāmil Muḥammad al-Rashīd. Suʻūdī relations with eastern Arabia and ʻUmān, 1800–1870 Luzac and Company, 1981 pp. 21–31 ^ Yitzhak Nakash (2011)Reaching for Power: The Shi'a in the Modern Arab World p. 22 ^ "Arabia, history of." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 30 November 2007. ^ Bernstein, William J. (2008) A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. pp. 191 ff ^ Chatterji, Nikshoy C. (1973). Muddle of the Middle East, Volume 2. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-391-00304-0. ^ Bowen 2007, p. 68. ^ "Saudi Arabia to commemorate 'Founding Day' on Feb. 22 annually: Royal order". Al Arabiya English. 27 January 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022. ^ "History of the Kingdom | kingdom of Saudi Arabia – Ministry of Foreign Affairs". www.mofa.gov.sa. Retrieved 15 February 2022. ^ Bowen 2007, p. 69–70. ^ Harris, Ian; Mews, Stuart; Morris, Paul; Shepherd, John (1992). Contemporary Religions: A World Guide. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-582-08695-1. ^ Faksh, Mahmud A. (1997). The Future of Islam in the Middle East. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-275-95128-3. ^ D. Gold (6 April 2003) "Reining in Riyadh". NYpost (JCPA) ^ "The Saud Family and Wahhabi Islam". Library of Congress Country Studies. ^ Murphy, David (2008). The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence Sets Arabia Ablaze. pp. 5–8. ISBN 978-1-84603-339-1. ^ Madawi Al Rasheed (1997). Politics in an Arabian Oasis: The Rashidis of Saudi Arabia. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-86064-193-0. ^ Anderson, Ewan W.; William Bayne Fisher (2000). The Middle East: Geography and Geopolitics. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-415-07667-8. ^ R. Hrair Dekmejian (1994). Islam in Revolution: Fundamentalism in the Arab World. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8156-2635-0. ^ Tucker, Spencer; Priscilla Mary Roberts (205). The Encyclopedia of World War I. p. 565. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. ^ Hourani, Albert (2005). A History of the Arab Peoples. pp. 315–319. ISBN 978-0-571-22664-1. ^ Wynbrandt, James; Gerges, Fawaz A. (2010). A Brief History of Saudi Arabia. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8160-7876-9. ^ Lacey, Robert (2009). Inside the Kingdom. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-09-953905-6. ^ "History of Saudi Arabia. ( The Saudi National Day 23, Sep )". Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. Retrieved 21 September 2018. ^ Mohamad Riad El-Ghonemy (1998). Afluence and Poverty in the Middle East. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-415-10033-5. ^ a b Al-Rasheed, pp. 136–137 ^ Joy Winkie Viola (1986). Human Resources Development in Saudi Arabia: Multinationals and Saudization. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-88746-070-8. ^ Rabasa, Angel; Benard, Cheryl; Chalk, Peter (2005). The Muslim world after 9/11. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8330-3712-1. ^ a b Toby Craig Jones (2010). Desert Kingdom: How Oil and Water Forged Modern Saudi Arabia. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-0-674-04985-7. ^ Hegghammer, p. 24 ^ Cordesman, Anthony H. (2003). Saudi Arabia Enters the 21st Century. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-275-98091-7. ^ El-Gamal, Mahmoud A. & Amy Myers Jaffe (2010). Oil, Dollars, Debt, and Crises: The Global Curse of Black Gold. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-72070-0. ^ Abir 1993, p. 114. ^ Robert Fisk (2005) The Great War For Civilisation. Fourth Estate. p. 23. ISBN 1-4000-7517-3 ^ Blanchard, Christopher (2009). Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations. United States Congressional Research Service. pp. 5–6. ^ Hegghammer, p. 31 ^ Al-Rasheed, p. 212 ^ Cordesman, Anthony H. (2009). Saudi Arabia: National Security in a Troubled Region. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-313-38076-1. ^ "Flood sparks rare action". Reuters via Montreal Gazette. 29 January 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. ^ "Dozens detained in Saudi over flood protests". The Peninsula (Qatar)/Thomson-Reuters. 29 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. ^ Fisk, Robert (5 May 2011). "Saudis mobilise thousands of troops to quell growing revolt". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. ^ "Saudi ruler offers $36bn to stave off uprising amid warning oil price could double". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. ^ "Saudi king gives billion-dollar cash boost to housing, jobs – Politics & Economics". Bloomberg via ArabianBusiness.com. 23 February 2011. ^ "King Abdullah Returns to Kingdom, Enacts Measures to Boost the Economy". U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. ^ "Saudi king announces new benefits". Al Jazeera. 23 February 2011. ^ "Saudi Arabia's king announces huge jobs and housing package". The Guardian. Associated Press. 18 March 2011. ^ Abu, Donna (18 March 2011). "Saudi King to Spend $67 Billion on Housing, Jobs in Bid to Pacify Citizens". Bloomberg. ^ al-Suhaimy, Abeed (23 March 2011). "Saudi Arabia announces municipal elections". Asharq al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2012. ^ Abu-Nasr, Donna (28 March 2011). "Saudi Women Inspired by Fall of Mubarak Step Up Equality Demand". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2 April 2011. ^ "Saudis vote in municipal elections, results on Sunday". Oman Observer. Agence France-Presse. 30 September 2011. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. ^ "Saudi Arabia". freedomhouse.org. 1 November 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2019. ^ Alisa, Shishkina; Issaev, Leonid (14 November 2018). "Internet Censorship in Arab Countries: Religious and Moral Aspects" (PDF). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019. Alt URL ^ "Saudi internet rules, 2001". al-bab.com. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Stay safe

WARNING: Do not in any way criticize or show any kind of disrespect to Islam, the Saudi royal family, the Saudi government, or the country in general. Simply avoid these topics if you can.

WARNING: Do not in any way criticize or show any kind of disrespect to Islam, the Saudi royal family, the Saudi government, or the country in general. Simply avoid these topics if you can.

Saudi Arabia is notorious for its extremely harsh punishments ranging from a lifetime of imprisonent and mistreatment to the death penalty. Offences that would normally be considered minor in other parts of the world (such as apostasy and adultery) are punishable by death. As long as you obey the law and respect local customs, your visit will be hassle free.

Saudi Arabia has one of the lowest crime rates in the world, owing to a notoriously harsh justice system. The system gives no leeway to non-Saudis, and embassies can provide only limited help in these situations. Saudi Arabia is considered by many to have one of the worst human rights records in the world. You need to watch what you say and do, always. As the saying goes, "If you have nothing good to say, don't say anything at all."

...Read moreStay safeRead less WARNING: Do not in any way criticize or show any kind of disrespect to Islam, the Saudi royal family, the Saudi government, or the country in general. Simply avoid these topics if you can.

WARNING: Do not in any way criticize or show any kind of disrespect to Islam, the Saudi royal family, the Saudi government, or the country in general. Simply avoid these topics if you can.

Saudi Arabia is notorious for its extremely harsh punishments ranging from a lifetime of imprisonent and mistreatment to the death penalty. Offences that would normally be considered minor in other parts of the world (such as apostasy and adultery) are punishable by death. As long as you obey the law and respect local customs, your visit will be hassle free.

Saudi Arabia has one of the lowest crime rates in the world, owing to a notoriously harsh justice system. The system gives no leeway to non-Saudis, and embassies can provide only limited help in these situations. Saudi Arabia is considered by many to have one of the worst human rights records in the world. You need to watch what you say and do, always. As the saying goes, "If you have nothing good to say, don't say anything at all."

DrivingThe biggest danger a visitor to Saudi Arabia faces is dangerous driving. Drivers typically tend to attack their art with an equal mix of aggressiveness and incompetence.

Illict drugsSaudi Arabia punishes drug offences severely. Drug trafficking and the consumption of narcotics will lead to a death sentence. Your entry card will mention this clearly as well.

Women travellersSaudi society endeavours to keep men and women separate, but sexual harassment — leers, jeers and even being followed — is depressingly common. Raising a ruckus or simply loudly asking the harasser anta Muslim? ("are you Muslim?") will usually suffice to scare them off.

Women should keep in mind that under Saudi law, four independent male witnesses are required to testify in order for someone to be convicted of rape. Failure to produce the four male witnesses will result in the woman being found guilty of pre-marital sex or adultery (which are crimes under Saudi law) instead.

If you are married to a Saudi national, you are subject to Saudi marital laws and the mahram system.

You and your children (if you have any) cannot leave the country or do just about anything (i.e. perform the Hajj, open a bank account, etc.) unless your husband or guardian approves. This system of guardianship can make it impossible for you, as a grown adult, to exercise full control over your own life. In the unfortunate event that your Saudi spouse dies, someone else ends up becoming your mahram. This could be your son, a sibling, and so on. If you divorce a Saudi national, it is next-to impossible to leave the country with any children that were born during the marriage, even if you've been granted custody of them. Saudi courts rarely grant this privilege unless there's a compelling reason to do so. Divorces that have taken place in other countries are not recognised by Saudi Arabia. If your children visit your (former) husband from abroad, they will not be allowed to leave unless he approves. If you had the misfortune of being married to an abusive spouse and are not prepared to deal with the prospect of never seeing your children again, encourage them to not go in the first place.LGBT travellersThe legal and cultural abhorrence against the LGBT community is far-reaching in Saudi Arabia. LGBT activities are illegal in Saudi Arabia, and they are punishable by death. If you fit in this category, it would be better to not visit Saudi Arabia at all.

Safety concernsA low-level insurgency which targets foreigners in general and Westerners in particular continues to simmer. The wave of violence in 2003-2004 has been squashed by a brutal crackdown by Saudi security forces and there have been no major attacks in the cities for several years, security remains tight and it is prudent not to draw too much attention to yourself. Foreigners should register their presence with their embassy or consulate. Emergency alert systems using e-mail and cell phone messages are maintained by many governments for their guest workers.

Four French tourists, part of a larger group that had been camping in the desert, were shot and killed by terrorists near Madain Saleh in early 2007. Due to this, mandatory police escorts — which can be an interesting experience, but can also be annoying, restrictive hassles — are sometimes provided for travel outside major cities, in areas like Abha, Najran and Madain Saleh.

Due to Saudi Arabia's involvement in the war against Houthi rebels in Yemen, there are occasional ballistic missile attacks against major Saudi cities and infrastructure. Follow the instructions of civil defense/emergency personnel if such attacks occur.