Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. Yellowstone was the first national park in the U.S. and is also widely held to be the first national park in the world. The park is known for its wildlife and its many geothermal features, especially the Old Faithful geyser, one of its most popular. While it represents many types of biomes, the subalpine forest is the most abundant. It is part of the South Central Rockies forests ecoregion.

While Native Americans have lived in the Yellowstone region for at least 11,000 years, aside from visits by mountain men during the early-to-mid-19th century, organized exploration did not begin until the late 1860s. Management and...Read more

Yellowstone National Park is a national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. Yellowstone was the first national park in the U.S. and is also widely held to be the first national park in the world. The park is known for its wildlife and its many geothermal features, especially the Old Faithful geyser, one of its most popular. While it represents many types of biomes, the subalpine forest is the most abundant. It is part of the South Central Rockies forests ecoregion.

While Native Americans have lived in the Yellowstone region for at least 11,000 years, aside from visits by mountain men during the early-to-mid-19th century, organized exploration did not begin until the late 1860s. Management and control of the park originally fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the first Secretary of the Interior to supervise the park being Columbus Delano. However, the U.S. Army was eventually commissioned to oversee the management of Yellowstone for 30 years between 1886 and 1916. In 1917, the administration of the park was transferred to the National Park Service, which had been created the previous year. Hundreds of structures have been built and are protected for their architectural and historical significance, and researchers have examined more than a thousand archaeological sites.

Yellowstone National Park spans an area of 3,468.4 sq mi (8,983 km2), comprising lakes, canyons, rivers, and mountain ranges. Yellowstone Lake is one of the largest high-elevation lakes in North America and is centered over the Yellowstone Caldera, the largest super volcano on the continent. The caldera is considered a dormant volcano. It has erupted with tremendous force several times in the last two million years. Well over half of the world's geysers and hydrothermal features are in Yellowstone, fueled by this ongoing volcanism. Lava flows and rocks from volcanic eruptions cover most of the land area of Yellowstone. The park is the centerpiece of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the largest remaining nearly intact ecosystem in the Earth's northern temperate zone. In 1978, Yellowstone was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Hundreds of species of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians have been documented, including several that are either endangered or threatened. The vast forests and grasslands also include unique species of plants. Yellowstone Park is the largest and most famous megafauna location in the contiguous United States. Grizzly bears, cougars, wolves, and free-ranging herds of bison and elk live in this park. The Yellowstone Park bison herd is the oldest and largest public bison herd in the United States. Forest fires occur in the park each year; in the large forest fires of 1988, nearly one-third of the park was burnt. Yellowstone has numerous recreational opportunities, including hiking, camping, boating, fishing, and sightseeing. Paved roads provide close access to the major geothermal areas as well as some of the lakes and waterfalls. During the winter, visitors often access the park by way of guided tours that use either snow coaches or snowmobiles.

The park contains the headwaters of the Yellowstone River, from which it takes its historical name. Near the end of the 18th century, French trappers named the river Roche Jaune, which is probably a translation of the Hidatsa name Mi tsi a-da-zi ("Yellow Stone River").[1] Later, American trappers rendered the French name in English as "Yellow Stone". Although it is commonly believed that the river was named for the yellow rocks seen in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Native American name source is unclear.[2]

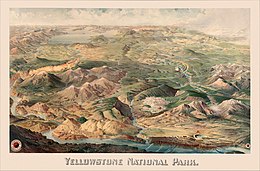

Detailed pictorial map from 1904

Detailed pictorial map from 1904The human history of the park began at least 11,000 years ago when Native Americans began to hunt and fish in the region.[3] During the construction of the post office in Gardiner, Montana, in the 1950s, an obsidian point of Clovis origin was found that dated from approximately 11,000 years ago.[4] These Paleo-Indians, of the Clovis culture, used the significant amounts of obsidian found in the park to make cutting tools and weapons. Arrowheads made of Yellowstone obsidian have been found as far away as the Mississippi Valley, indicating that a regular obsidian trade existed between local tribes and tribes farther east.[5] When the Lewis and Clark Expedition entered present-day Montana in 1805 they encountered the Nez Perce, Crow, and Shoshone tribes who described to them the Yellowstone region to the south, but they chose not to investigate.[6]

In 1806, John Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, left to join a group of fur trappers. After splitting up with the other trappers in 1807, Colter passed through a portion of what later became the park, during the winter of 1807–1808. He observed at least one geothermal area in the northeastern section of the park, near Tower Fall.[7] After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with members of the Crow and Blackfoot tribes in 1809, Colter described a place of "fire and brimstone" that most people dismissed as delirium; the supposedly mystical place was nicknamed "Colter's Hell". Over the next 40 years, numerous reports from mountain men and trappers told of boiling mud, steaming rivers, and petrified trees, yet most of these reports were believed at the time to be a myth.[8]

After an 1856 exploration, mountain man Jim Bridger (also believed to be the first or second European American to have seen the Great Salt Lake) reported observing boiling springs, spouting water, and a mountain of glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored because Bridger was a known "spinner of yarns". In 1859, a U.S. Army Surveyor named Captain William F. Raynolds embarked on a two-year survey of the southern central Rockies. After wintering in Wyoming, in May 1860, Raynolds and his party—which included geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden and guide Jim Bridger—attempted to cross the Continental Divide over Two Ocean Plateau from the Wind River drainage in northwest Wyoming. Heavy spring snows prevented their passage but had they been able to traverse the divide, the party would have been the first organized survey to enter the Yellowstone region.[9] The American Civil War hampered further organized explorations until the late 1860s.[10]

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829–1887), an American geologist who convinced Congress to make Yellowstone a national park in 1872

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829–1887), an American geologist who convinced Congress to make Yellowstone a national park in 1872The first detailed expedition to the Yellowstone area was the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition of 1869, which consisted of three privately funded explorers. The Folsom party followed the Yellowstone River to Yellowstone Lake.[11] The members of the Folsom party kept a journal and based on the information it reported, a party of Montana residents organized the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition in 1870. It was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana Henry Washburn, and included Nathaniel P. Langford (who later became known as "National Park" Langford) and a U.S. Army detachment commanded by Lt. Gustavus Doane. The expedition spent about a month exploring the region, collecting specimens, and naming sites of interest.[12]

A Montana writer and lawyer named Cornelius Hedges, who had been a member of the Washburn expedition, proposed that the region should be set aside and protected as a national park; he wrote detailed articles about his observations for the Helena Herald newspaper between 1870 and 1871. Hedges essentially restated comments made in October 1865 by acting Montana Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher, who had previously commented that the region should be protected.[13] Others made similar suggestions. An 1871 letter to Ferdinand V. Hayden from Jay Cooke, a businessman who wanted to bring tourists to the region, encouraged him to mention it in his official report of the survey.[14] Cooke wrote that his friend, Congressman William D. Kelley had also suggested "Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever".[15]

Park creation Ferdinand V. Hayden's map of Yellowstone National Park, 1871

Ferdinand V. Hayden's map of Yellowstone National Park, 1871In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort, Ferdinand V. Hayden was finally able to explore the region.[3] With government sponsorship, he returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from public auction. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed The Act of Dedication[16] law that created Yellowstone National Park.[17]

Hayden, while not the only person to have thought of creating a park in the region, was its first and most enthusiastic advocate.[18] He believed in "setting aside the area as a pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" and warned that there were those who would come and "make merchandise of these beautiful specimens".[18] Worrying the area could face the same fate as Niagara Falls, he concluded the site should "be as free as the air or Water".[18] In his report to the Committee on Public Lands, he concluded that if the bill failed to become law, "the vandals who are now waiting to enter into this wonder-land, will in a single season despoil, beyond recovery, these remarkable curiosities, which have required all the cunning skill of nature thousands of years to prepare".[19][20]

Hayden and his 1871 party recognized Yellowstone as a unique place that should be available for further research. He also was encouraged to preserve it for others to see and experience it as well. In 1873, Congress authorized and funded a survey to find a wagon route to the park from the south which was completed by the Jones Expedition of 1873.[21] Eventually the railroads and, sometime after that, the automobile would make that possible. The park was not set aside strictly for ecological purposes. Hayden imagined something akin to the scenic resorts and baths in England, Germany, and Switzerland.[18]

THE ACT OF DEDICATION[20]

AN ACT to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the tract of land in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming ... is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people; and all persons who shall locate, or settle upon, or occupy the same or any part thereof, except as hereinafter provided, shall be considered trespassers and removed there from ...

Approved March 1, 1872.

Signed by:

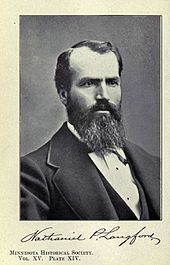

ULYSSES S. GRANT, President of the United States. SCHUYLER COLFAX, Vice-President of the United States and President of the Senate. JAMES G. BLAINE, Speaker of the House. Portrait of Nathaniel P. Langford (1870), the first superintendent of the park[22]

Portrait of Nathaniel P. Langford (1870), the first superintendent of the park[22]There was considerable local opposition to Yellowstone National Park during its early years. Some of the locals feared that the regional economy would be unable to thrive if there remained strict federal prohibitions against resource development or settlement within park boundaries and local entrepreneurs advocated reducing the size of the park so that mining, hunting, and logging activities could be developed.[23] To this end, numerous bills were introduced into Congress by Montana representatives who sought to remove the federal land-use restrictions.[24]

After the park's official formation, Nathaniel Langford was appointed as the park's first superintendent in 1872 by the Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano, the first overseer and controller of the park.[25] Langford served for five years but was denied a salary, funding, and staff. Langford lacked the means to improve the land or properly protect the park, and without formal policy or regulations, he had few legal methods to enforce such protection. This left Yellowstone vulnerable to poachers, vandals, and others seeking to raid its resources. He addressed the practical problems park administrators faced in the 1872 Report to the Secretary of the Interior[26] and correctly predicted that Yellowstone would become a major international attraction deserving the continuing stewardship of the government. In 1874, both Langford and Delano advocated the creation of a federal agency to protect the vast park, but Congress refused. In 1875, Colonel William Ludlow, who had previously explored areas of Montana under the command of George Armstrong Custer, was assigned to organize and lead an expedition to Montana and the newly established Yellowstone Park. Observations about the lawlessness and exploitation of park resources were included in Ludlow's Report of a Reconnaissance to the Yellowstone National Park. The report included letters and attachments by other expedition members, including naturalist and mineralogist George Bird Grinnell.[27]

Great Falls of the Yellowstone, U.S. Geological and Geographic Survey of the Territories (1874–1879), photographer William Henry Jackson

Great Falls of the Yellowstone, U.S. Geological and Geographic Survey of the Territories (1874–1879), photographer William Henry JacksonGrinnell documented the poaching of buffalo, deer, elk, and antelope for hides: "It is estimated that during the winter of 1874–1875, not less than 3,000 buffalo and mule deer suffer even more severely than the elk, and the antelope nearly as much."[28]

As a result, Langford was forced to step down in 1877.[29][30] Having traveled through Yellowstone and witnessed land management problems, Philetus Norris volunteered for the position following Langford's exit. Congress finally saw fit to implement a salary for the position, as well as to provide minimal funding to operate the park. Norris used these funds to expand access to the park, building numerous crude roads and facilities.[30]

In 1880, Harry Yount was appointed as a gamekeeper to control poaching and vandalism in the park. Yount had previously spent decades exploring the mountain country of present-day Wyoming, including the Grand Tetons, after joining F V. Hayden's Geological Survey in 1873.[31] Yount is the first national park ranger,[32] and Yount's Peak, at the head of the Yellowstone River, was named in his honor.[33] These measures still proved to be insufficient in protecting the park, as neither Norris nor the three superintendents who followed, were given sufficient manpower or resources.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Native American tribes were effectively excluded from the national park.[3] Under a half-dozen tribes had made seasonal use of the Yellowstone area- the only year-round residents were small bands of Eastern Shoshone known as "Sheepeaters". They left the area under the assurances of a treaty negotiated in 1868, under which the Sheepeaters ceded their lands but retained the right to hunt in Yellowstone. The United States never ratified the treaty and refused to recognize the claims of the Sheepeaters or any other tribe that had used Yellowstone.[34]

The Nez Perce band associated with Chief Joseph, numbering about 750 people, passed through Yellowstone National Park in thirteen days in late August 1877. They were being pursued by the U.S. Army and entered the national park about two weeks after the Battle of the Big Hole. Some of the Nez Perce were friendly to the tourists and other people they encountered in the park; some were not. Nine park visitors were briefly taken captive. Despite Joseph and other chiefs ordering that no one should be harmed, at least two people were killed and several wounded.[35][36] One of the areas where encounters occurred was in Lower Geyser Basin and east along a branch of the Firehole River to Mary Mountain and beyond.[35] That stream was named Nez Perce Creek in memory of their trail through the area.[37] A group of Bannocks entered the park in 1878, alarming park Superintendent Philetus Norris. In the aftermath of the Sheepeater Indian War of 1879, Norris built a fort to prevent Native Americans from entering the national park.[34][36]

Fort Yellowstone (circa 1910), formerly a U.S. Army post, now serves as park headquarters.

Fort Yellowstone (circa 1910), formerly a U.S. Army post, now serves as park headquarters.The Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in Livingston, Montana, as a gateway terminus to connect to the northern entrance area in 1883, which helped to increase visitation from 300 in 1872 to 5,000 in 1883.[38] The spur line was completed in fall of that year from Livingston to Cinnabar for stage connection to Mammoth, then in 1902 extended to Gardiner station, where passengers also switched to stagecoach.[39] Visitors in these early years faced poor and dusty roads plus limited services, with automobiles first admitted in phases beginning only in 1915. By 1901 a Chicago, Burlington & Quincy connection opened via Cody and in 1908 a Union Pacific Railroad connection to West Yellowstone, followed by a 1927 Milwaukee Road connection to Gallatin Gateway near Bozeman, also motorcoaching visitors via West Yellowstone. Rail visitation fell off considerably by World War II and ceased regular service in favor of the automobile around the 1960s, though special excursions occasionally continued into the early 1980s.

Ongoing poaching and destruction of natural resources continued unabated until the U.S. Army arrived at Mammoth Hot Springs in 1886 and built Camp Sheridan. Over the next 22 years, as the army constructed permanent structures, Camp Sheridan was renamed Fort Yellowstone.[40] On May 7, 1894, the Boone and Crockett Club, acting through the personality of George G. Vest, Arnold Hague, William Hallett Phillips, W. A. Wadsworth, Archibald Rogers, Theodore Roosevelt, and George Bird Grinnell were successful in carrying through the Park Protection Act, which saved the park.[41] The Lacey Act of 1900 provided legal support for the officials prosecuting poachers. With the funding and manpower necessary to keep a diligent watch, the army developed its own policies and regulations that permitted public access while protecting park wildlife and natural resources. When the National Park Service was created in 1916, many of the management principles developed by the army were adopted by the new agency.[40] The army turned control over to the National Park Service on October 31, 1918.[42]

In 1898, the naturalist John Muir described the park as follows:

However orderly your excursions or aimless, again and again amid the calmest, stillest scenery you will be brought to a standstill hushed and awe-stricken before phenomena wholly new to you. Boiling springs and huge deep pools of purest green and azure water, thousands of them, are plashing and heaving in these high, cool mountains as if a fierce furnace fire were burning beneath each one of them; and a hundred geysers, white torrents of boiling water and steam, like inverted waterfalls, are ever and anon rushing up out of the hot, black underworld.[43]

Automobiles and further development Superintendent Horace M. Albright and black bears (1922). Tourists often fed black bears in the park's early years, with 527 injuries reported from 1931 to 1939.[44]

Superintendent Horace M. Albright and black bears (1922). Tourists often fed black bears in the park's early years, with 527 injuries reported from 1931 to 1939.[44]By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel on roads was eventually prohibited.[45]

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a New Deal relief agency for young men, played a major role between 1933 and 1942 in developing Yellowstone facilities. CCC projects included reforestation, campground development of many of the park's trails and campgrounds, trail construction, fire hazard reduction, and fire-fighting work. The CCC built the majority of the early visitor centers, campgrounds, and the current system of park roads.[46]

During World War II, tourist travel fell sharply, staffing was cut, and many facilities fell into disrepair.[47] By the 1950s, visitation increased tremendously in Yellowstone and other national parks. To accommodate the increased visitation, park officials implemented Mission 66, an effort to modernize and expand park service facilities. Planned to be completed by 1966, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service, Mission 66 construction diverged from the traditional log cabin style with design features of a modern style.[48] During the late 1980s, most construction styles in Yellowstone reverted to the more traditional designs. After the enormous forest fires of 1988 damaged much of Grant Village, structures there were rebuilt in the traditional style. The visitor center at Canyon Village, which opened in 2006, incorporates a more traditional design as well.[49]

The Roosevelt Arch in Gardiner, Montana, at the north entrance

The Roosevelt Arch in Gardiner, Montana, at the north entranceThe 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at Hebgen Lake damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs became turbid.[50] It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, the United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the Leopold Report, the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks had been ineffective, and recommended the management of Yellowstone's elk population.[51]

The wildfires during the summer of 1988 were the largest in the history of the park. Approximately 793,880 acres (3,210 km2; 1,240 sq mi) or 36% of the parkland was impacted by the fires, leading to a systematic re-evaluation of fire management policies. The fire season of 1988 was considered normal until a combination of drought and heat by mid-July contributed to an extreme fire danger. On "Black Saturday", August 20, 1988, strong winds expanded the fires rapidly, and more than 150,000 acres (610 km2; 230 sq mi) burned.[52]

On October 1, 2013, Yellowstone National Park closed due to the 2013 United States federal government shutdown. [53]

Add new comment