San Francisco ( SAN frən-SISS-koh; Spanish for 'Saint Francis'), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, financial, and cultural center in Northern California. With a population of 808,437 residents in 2022, San Francisco is the fourth most populous city in the U.S. state of California. The city covers a land area of 46.9 square miles (121 square kilometers) at the end of the San Francisco Peninsula, making it the second-most densely populated large U.S. city after New York City and the fifth-most densely populated U.S. county, behind only four New York City boroughs. Among the 92 U.S. cities proper with over 250,000 residents, San Francisco was ranked first by per capita income and sixth by aggregate income as of 2022. Colloquial nicknames for San Francisco include Frisco, San Fran, The City, and SF...Read more

San Francisco ( SAN frən-SISS-koh; Spanish for 'Saint Francis'), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, financial, and cultural center in Northern California. With a population of 808,437 residents in 2022, San Francisco is the fourth most populous city in the U.S. state of California. The city covers a land area of 46.9 square miles (121 square kilometers) at the end of the San Francisco Peninsula, making it the second-most densely populated large U.S. city after New York City and the fifth-most densely populated U.S. county, behind only four New York City boroughs. Among the 92 U.S. cities proper with over 250,000 residents, San Francisco was ranked first by per capita income and sixth by aggregate income as of 2022. Colloquial nicknames for San Francisco include Frisco, San Fran, The City, and SF (although Frisco and San Fran are generally not used by locals).

Prior to European settlement, the modern city proper was inhabited by the Yelamu, who spoke a language now referred to as Ramaytush Ohlone. On June 29, 1776, settlers from New Spain established the Presidio of San Francisco at the Golden Gate, and the Mission San Francisco de Asís a few miles away, both named for Francis of Assisi. The California Gold Rush of 1849 brought rapid growth, transforming an unimportant hamlet into a busy port, making it the largest city on the West Coast at the time; between 1870 and 1900, approximately one quarter of California's population resided in the city proper. In 1856, San Francisco became a consolidated city-county. After three-quarters of the city was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire, it was quickly rebuilt, hosting the Panama-Pacific International Exposition nine years later. In World War II, it was a major port of embarkation for naval service members shipping out to the Pacific Theater. In 1945, the United Nations Charter was signed in San Francisco, establishing the United Nations and in 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers. After the war, the confluence of returning servicemen, significant immigration, liberalizing attitudes, the rise of the beatnik and hippie countercultures, the sexual revolution, the peace movement growing from opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War, and other factors led to the Summer of Love and the gay rights movement, cementing San Francisco as a center of liberal activism in the United States.

San Francisco and the surrounding San Francisco Bay Area are a global center of economic activity and the arts and sciences, spurred by leading universities, high-tech, healthcare, finance, insurance, real estate, and professional services sectors. As of 2020, the metropolitan area, with 6.7 million residents, ranked 5th by GDP ($874 billion) and 2nd by GDP per capita ($131,082) across the OECD countries, ahead of global cities like Paris, London, and Singapore. San Francisco anchors the 13th most populous metropolitan statistical area in the United States with 4.6 million residents, and the fourth-largest by aggregate income and economic output, with a GDP of $729 billion in 2022. The wider San Jose–San Francisco–Oakland Combined Statistical Area is the fifth-most populous, with 9.0 million residents, and the third-largest by economic output, with a GDP of $1.32 trillion in 2022. In the same year, San Francisco proper had a GDP of $252.2 billion, and a GDP per capita of $312,000. San Francisco was ranked fifth in the world and second in the United States on the Global Financial Centres Index as of September 2023. Despite a post-COVID-19 pandemic exodus of business from the downtown core, the economy of the city proper grew by 15.5% between 2019 and 2022 and is still home to numerous companies inside and outside of technology, including Wells Fargo, Salesforce, Uber, Airbnb, X Corp. (formerly Twitter), Levi's, Gap, Dropbox, and Lyft.

In 2022, San Francisco had more than 1.7 million international visitors - the fifth-most visited city from abroad in the United States after New York City, Miami, Orlando, and Los Angeles - and approximately 20 million domestic visitors for a total of 21.9 million visitors. The city is known for its steep rolling hills and eclectic mix of architecture across varied neighborhoods, as well as its cool summers, fog, and landmarks, including the Golden Gate Bridge, cable cars, and Alcatraz, along with the Chinatown and Mission districts. The city is home to a number of educational and cultural institutions, such as the University of California, San Francisco, the University of San Francisco, San Francisco State University, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the de Young Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Symphony, the San Francisco Ballet, the San Francisco Opera, the SFJAZZ Center, and the California Academy of Sciences. Two major league sports teams, the San Francisco Giants and the Golden State Warriors, play their home games within San Francisco proper. San Francisco's main international airport offers flights to over 125 destinations while a light rail and bus network, in tandem with the BART and Caltrain systems, connects nearly every part of San Francisco with the wider region.

The earliest archeological evidence of human habitation of the territory of San Francisco dates to 3000 BCE.[1] The Yelamu group of the Ramaytush people resided in a few small villages when an overland Spanish exploration party arrived on November 2, 1769, the first documented European visit to San Francisco Bay.[2] The Ohlone name for San Francisco was Ahwaste, meaning, "place at the bay".[3] The arrival of Spanish colonists, and the implementation of their Mission system, marked the beginning of the genocide of the Ramaytush people, and the deprivation of language and culture.[4][5][6]

Spanish era Juan Bautista de Anza established the Presidio of San Francisco for the Spanish Empire in 1776.

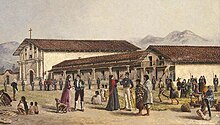

Juan Bautista de Anza established the Presidio of San Francisco for the Spanish Empire in 1776. Mission San Francisco de Asís was founded by Padre Francisco Palóu on October 9, 1776.

Mission San Francisco de Asís was founded by Padre Francisco Palóu on October 9, 1776.The Spanish Empire claimed San Francisco as part of Las Californias, a province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spanish first arrived in what is now San Francisco on November 2, 1769, when the Portolá expedition led by Don Gaspar de Portolá and Juan Crespí arrived at San Francisco Bay. Having noted the strategic benefits of the area due to its large natural harbor, the Spanish dispatched Pedro Fages in 1770 to find a more direct route to the San Francisco Peninsula from Monterey, which would become part of the El Camino Real route. By 1774, Juan Bautista de Anza had arrived to the area to select the sites for a mission and presidio. The first European maritime presence in San Francisco Bay occurred on August 5, 1775, when the Spanish ship San Carlos, commanded by Juan Manuel de Ayala, became the first ship to anchor in the bay.[7]

Soon after, on March 28, 1776, Anza established the Presidio of San Francisco. On October 9, Mission San Francisco de Asís, also known as Mission Dolores, was founded by Padre Francisco Palóu.[8] In 1794, the Presidio established the Castillo de San Joaquín, a fortification on the southern side of the Golden Gate, which later came to be known as Fort Point.

In 1804, the province of Alta California was created, which included Yerba Buena - the former name of San Francisco. At its peak in 1810–1820, the average population at the Mission Dolores settlement was about 1,100 people.[9]

Mexican era Juana Briones de Miranda, known as the "Founding Mother of San Francisco"[10]

Juana Briones de Miranda, known as the "Founding Mother of San Francisco"[10]In 1821, the Californias were ceded to Mexico by Spain. The extensive California mission system gradually lost its influence during the period of Mexican rule. Agricultural land became largely privatized as ranchos, as was occurring in other parts of California. Coastal trade increased, including a half-dozen barques from various Atlantic ports which regularly sailed in California waters.[11][12]

Yerba Buena (after a native herb), a trading post with settlements between the Presidio and Mission grew up around the Plaza de Yerba Buena. The plaza was later renamed Portsmouth Square (now located in the city's Chinatown and Financial District). The Presidio was commanded in 1833 by Captain Mariano G. Vallejo.[11]

In 1833, Juana Briones de Miranda built her rancho near El Polín Spring, founding the first civilian household in San Francisco, which had previously only been comprised by the military settlement at the Presidio and the religious settlement at Mission Dolores.[10]

In 1834, Francisco de Haro became the first Alcalde of Yerba Buena. De Haro was a native of Mexico, from that nation's west coast city of Compostela, Nayarit. A land survey of Yerba Buena was made by the Swiss immigrant Jean Jacques Vioget as prelude to the city plan. The second Alcalde José Joaquín Estudillo was a Californio from a prominent Monterey family. In 1835, while in office, he approved the first land grant in Yerba Buena: to William Richardson, a naturalized Mexican citizen of English birth. Richardson had arrived in San Francisco aboard a whaling ship in 1822. In 1825, he married Maria Antonia Martinez, eldest daughter of the Californio Ygnacio Martínez.[13][a]

The 1846 Battle of Yerba Buena was an early U.S. victory in the American conquest of California.

The 1846 Battle of Yerba Buena was an early U.S. victory in the American conquest of California.Yerba Buena began to attract American and European settlers; an 1842 census listed 21 residents (11%) born in the United States or Europe, as well as one Filipino merchant.[14] Following the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma and the beginning of the U.S. Conquest of California, American forces under the command of John B. Montgomery captured Yerba Buena on July 9, 1846, with little resistance from the local Californio population. At the end of the month, the Brooklyn arrived with a group of Mormon settlers, who had departed New York City six months earlier. Following the capture, U.S. forces appointed both José de Jesús Noé and Washington Allon Bartlett to serve as co-alcaldes (mayors), while the conquest continued on in the rest of California. Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, Alta California was ceded from Mexico to the United States.

Post-Conquest era San Francisco in 1849, during the beginning of the California Gold Rush

San Francisco in 1849, during the beginning of the California Gold Rush Port of San Francisco in 1851

Port of San Francisco in 1851Despite its attractive location as a port and naval base, post-Conquest San Francisco was still a small settlement with inhospitable geography.[15] Its 1847 population was said to be 459.[11]

The California Gold Rush brought a flood of treasure seekers (known as "forty-niners", as in "1849"). With their sourdough bread in tow,[16] prospectors accumulated in San Francisco over rival Benicia,[17] raising the population from 1,000 in 1848 to 25,000 by December 1849.[18] The promise of wealth was so strong that crews on arriving vessels deserted and rushed off to the gold fields, leaving behind a forest of masts in San Francisco harbor.[19] Some of these approximately 500 abandoned ships were used at times as storeships, saloons, and hotels; many were left to rot, and some were sunk to establish title to the underwater lot. By 1851, the harbor was extended out into the bay by wharves while buildings were erected on piles among the ships. By 1870, Yerba Buena Cove had been filled to create new land. Buried ships are occasionally exposed when foundations are dug for new buildings.[20]

California was quickly granted statehood in 1850, and the U.S. military built Fort Point at the Golden Gate and a fort on Alcatraz Island to secure the San Francisco Bay. San Francisco County was one of the state's 18 original counties established at California statehood in 1850.[21] Until 1856, San Francisco's city limits extended west to Divisadero Street and Castro Street, and south to 20th Street. In 1856, the California state government divided the county. A straight line was then drawn across the tip of the San Francisco Peninsula just north of San Bruno Mountain. Everything south of the line became the new San Mateo County while everything north of the line became the new consolidated City and County of San Francisco.[22]

The Bank of California, established in 1863, was the first commercial bank in Western United States.[23]

The Bank of California, established in 1863, was the first commercial bank in Western United States.[23]Entrepreneurs sought to capitalize on the wealth generated by the Gold Rush. Silver discoveries, including the Comstock Lode in Nevada in 1859, further drove rapid population growth.[24] With hordes of fortune seekers streaming through the city, lawlessness was common, and the Barbary Coast section of town gained notoriety as a haven for criminals, prostitution, bootlegging, and gambling.[25] Early winners were the banking industry, with the founding of Wells Fargo in 1852 and the Bank of California in 1864.

Development of the Port of San Francisco and the establishment in 1869 of overland access to the eastern U.S. rail system via the newly completed Pacific Railroad (the construction of which the city only reluctantly helped support[26]) helped make the Bay Area a center for trade. Catering to the needs and tastes of the growing population, Levi Strauss opened a dry goods business and Domingo Ghirardelli began manufacturing chocolate. Chinese immigrants made the city a polyglot culture, drawn to "Old Gold Mountain", creating the city's Chinatown quarter. By 1880, Chinese made up 9.3% of the population.[27]

View of the city in 1878

View of the city in 1878The first cable cars carried San Franciscans up Clay Street in 1873. The city's sea of Victorian houses began to take shape, and civic leaders campaigned for a spacious public park, resulting in plans for Golden Gate Park. San Franciscans built schools, churches, theaters, and all the hallmarks of civic life. The Presidio developed into the most important American military installation on the Pacific coast.[28] By 1890, San Francisco's population approached 300,000, making it the eighth-largest city in the United States at the time. Around 1901, San Francisco was a major city known for its flamboyant style, stately hotels, ostentatious mansions on Nob Hill, and a thriving arts scene.[29] The first North American plague epidemic was the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904.[30]

1906 earthquake and interwar era The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was the deadliest earthquake in U.S. history.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was the deadliest earthquake in U.S. history.At 5:12 am on April 18, 1906, a major earthquake struck San Francisco and northern California. As buildings collapsed from the shaking, ruptured gas lines ignited fires that spread across the city and burned out of control for several days. With water mains out of service, the Presidio Artillery Corps attempted to contain the inferno by dynamiting blocks of buildings to create firebreaks.[31] More than three-quarters of the city lay in ruins, including almost all of the downtown core.[32] Contemporary accounts reported that 498 people died, though modern estimates put the number in the several thousands.[33] More than half of the city's population of 400,000 was left homeless.[34] Refugees settled temporarily in makeshift tent villages in Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, on the beaches, and elsewhere. Many fled permanently to the East Bay. Jack London is remembered for having famously eulogized the earthquake: "Not in history has a modern imperial city been so completely destroyed. San Francisco is gone."[35]

The reconstruction of San Francisco City Hall on Civic Center Plaza, c. 1913–16

The reconstruction of San Francisco City Hall on Civic Center Plaza, c. 1913–16Rebuilding was rapid and performed on a grand scale. Rejecting calls to completely remake the street grid, San Franciscans opted for speed.[36] Amadeo Giannini's Bank of Italy, later to become Bank of America, provided loans for many of those whose livelihoods had been devastated. The influential San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association or SPUR was founded in 1910 to address the quality of housing after the earthquake.[37] The earthquake hastened development of western neighborhoods that survived the fire, including Pacific Heights, where many of the city's wealthy rebuilt their homes.[38] In turn, the destroyed mansions of Nob Hill became grand hotels. City Hall rose again in the Beaux Arts style, and the city celebrated its rebirth at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in 1915.[39]

The Panama–Pacific Exposition, a major world's fair held in 1915, was seen as a chance to showcase the city's recovery from the earthquake.

The Panama–Pacific Exposition, a major world's fair held in 1915, was seen as a chance to showcase the city's recovery from the earthquake.During this period, San Francisco built some of its most important infrastructure. Civil Engineer Michael O'Shaughnessy was hired by San Francisco Mayor James Rolph as chief engineer for the city in September 1912 to supervise the construction of the Twin Peaks Reservoir, the Stockton Street Tunnel, the Twin Peaks Tunnel, the San Francisco Municipal Railway, the Auxiliary Water Supply System, and new sewers. San Francisco's streetcar system, of which the J, K, L, M, and N lines survive today, was pushed to completion by O'Shaughnessy between 1915 and 1927. It was the O'Shaughnessy Dam, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, and Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct that would have the largest effect on San Francisco.[40] An abundant water supply enabled San Francisco to develop into the city it has become today.

The Bay Bridge under construction on Yerba Buena Island in 1935

The Bay Bridge under construction on Yerba Buena Island in 1935In ensuing years, the city solidified its standing as a financial capital; in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, not a single San Francisco-based bank failed.[41] Indeed, it was at the height of the Great Depression that San Francisco undertook two great civil engineering projects, simultaneously constructing the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge, completing them in 1936 and 1937, respectively. It was in this period that the island of Alcatraz, a former military stockade, began its service as a federal maximum security prison, housing notorious inmates such as Al Capone, and Robert Franklin Stroud, the Birdman of Alcatraz. San Francisco later celebrated its regained grandeur with a World's fair, the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939–40, creating Treasure Island in the middle of the bay to house it.[42]

Contemporary era The United Nations was created in San Francisco in 1945, when the United Nations Charter was signed at the San Francisco Conference.

The United Nations was created in San Francisco in 1945, when the United Nations Charter was signed at the San Francisco Conference.During World War II, the city-owned Sharp Park in Pacifica was used as an internment camp to detain Japanese Americans.[43] Hunters Point Naval Shipyard became a hub of activity, and Fort Mason became the primary port of embarkation for service members shipping out to the Pacific Theater of Operations.[44] The explosion of jobs drew many people, especially African Americans from the South, to the area. After the end of the war, many military personnel returning from service abroad and civilians who had originally come to work decided to stay. The United Nations Charter creating the United Nations was drafted and signed in San Francisco in 1945 and, in 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers.[45]

Urban planning projects in the 1950s and 1960s involved widespread destruction and redevelopment of west-side neighborhoods and the construction of new freeways, of which only a series of short segments were built before being halted by citizen-led opposition.[46] The onset of containerization made San Francisco's small piers obsolete, and cargo activity moved to the larger Port of Oakland.[47] The city began to lose industrial jobs and turned to tourism as the most important segment of its economy.[48] The suburbs experienced rapid growth, and San Francisco underwent significant demographic change, as large segments of the white population left the city, supplanted by an increasing wave of immigration from Asia and Latin America.[49][50] From 1950 to 1980, the city lost over 10 percent of its population.

The Summer of Love in 1967 was an influential counterculture phenomenon with as many as 100,000 people converging in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood.

The Summer of Love in 1967 was an influential counterculture phenomenon with as many as 100,000 people converging in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood.Over this period, San Francisco became a magnet for America's counterculture movement. Beat Generation writers fueled the San Francisco Renaissance and centered on the North Beach neighborhood in the 1950s.[51] Hippies flocked to Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, reaching a peak with the 1967 Summer of Love.[52] In 1974, the Zebra murders left at least 16 people dead.[53] In the 1970s, the city became a center of the gay rights movement, with the emergence of The Castro as an urban gay village, the election of Harvey Milk to the Board of Supervisors, and his assassination, along with that of Mayor George Moscone, in 1978.[54]

Bank of America, now based in Charlotte, North Carolina, was founded in San Francisco; the bank completed 555 California Street in 1969. The Transamerica Pyramid was completed in 1972,[55] igniting a wave of "Manhattanization" that lasted until the late 1980s, a period of extensive high-rise development downtown.[56] The 1980s also saw a dramatic increase in the number of homeless people in the city, an issue that remains today, despite many attempts to address it.[57]

Transamerica Pyramid, built in 1972, characterized the Manhattanization of the city's skyline in the 1970–80's.

Transamerica Pyramid, built in 1972, characterized the Manhattanization of the city's skyline in the 1970–80's.The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake caused destruction and loss of life throughout the Bay Area. In San Francisco, the quake severely damaged structures in the Marina and South of Market districts and precipitated the demolition of the damaged Embarcadero Freeway and much of the damaged Central Freeway, allowing the city to reclaim The Embarcadero as its historic downtown waterfront and revitalizing the Hayes Valley neighborhood.[58]

The two recent decades have seen booms driven by the internet industry. During the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, startup companies invigorated the San Francisco economy. Large numbers of entrepreneurs and computer application developers moved into the city, followed by marketing, design, and sales professionals, changing the social landscape as once poorer neighborhoods became increasingly gentrified.[59] Demand for new housing and office space ignited a second wave of high-rise development, this time in the South of Market district.[60] By 2000, the city's population reached new highs, surpassing the previous record set in 1950. When the bubble burst in 2001 and again in 2023, many of these companies folded and their employees were laid off. Yet high technology and entrepreneurship remain mainstays of the San Francisco economy. By the mid-2000s (decade), the social media boom had begun, with San Francisco becoming a popular location for tech offices and a common place to live for people employed in Silicon Valley companies such as Apple and Google.[61]

The early 2020s featured an exodus of tech companies from Downtown San Francisco, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic; although San Francisco has since been widely characterized in the media to have entered an indefinite economic doom loop,[62][63] other sources have refuted this broad-based characterization of the city as a whole, asserting that the issues of concern are restricted primarily to the urban core of San Francisco.[64]

The Ferry Station Post Office Building, Armour & Co. Building, Atherton House, and YMCA Hotel are historic buildings among dozens of historical landmarks in the city, according to the National Register of Historic Places listings in San Francisco.[65]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment