Sainte-Chapelle

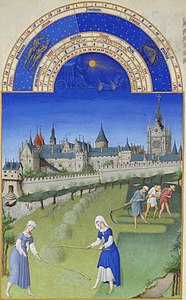

The Sainte-Chapelle (French: [sɛ̃t ʃapɛl]; English: Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

Construction began sometime after 1238 and the chapel was consecrated on 26 April 1248. The Sainte-Chapelle is considered among the highest achievements of the Rayonnant period of Gothic architecture. It was commissioned by King Louis IX of France to house his collection of Passion relics, including Christ's Crown of Thorns – one of the most important relics in medieval Christendom. This was later held in the nearby Notre-Dame Cathedral until the 2019 fire, which it survived.

Along with the Conciergerie, Sainte-Chapelle is one of the earliest surviving buildings of the Capetian royal pa...Read more

The Sainte-Chapelle (French: [sɛ̃t ʃapɛl]; English: Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

Construction began sometime after 1238 and the chapel was consecrated on 26 April 1248. The Sainte-Chapelle is considered among the highest achievements of the Rayonnant period of Gothic architecture. It was commissioned by King Louis IX of France to house his collection of Passion relics, including Christ's Crown of Thorns – one of the most important relics in medieval Christendom. This was later held in the nearby Notre-Dame Cathedral until the 2019 fire, which it survived.

Along with the Conciergerie, Sainte-Chapelle is one of the earliest surviving buildings of the Capetian royal palace on the Île de la Cité. Although damaged during the French Revolution and restored in the 19th century, it has one of the most extensive 13th-century stained glass collections anywhere in the world.

The chapel is now operated as a museum by the French Centre of National Monuments, along with the nearby Conciergerie, the other remaining vestige of the original palace.

Sainte-Chapelle was inspired by the earlier Carolingian royal chapels, notably the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne at his palace in Aix-la-Chapelle (now Aachen). It was built in about 800 and served as the oratory of the Emperor. In 1238 Louis IX had already built one royal chapel, attached to the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. This earlier chapel had only one level; its plan, on a much grander scale, was adapted for Sainte-Chapelle. [1]

The two levels of the new chapel, equal in size, had entirely different purposes. The upper level, where the sacred relics were kept, was reserved exclusively for the royal family and their guests. The lower level was used by the courtiers, servants, and soldiers of the palace. It was a very large structure, 36 meters (118 ft) long, 17 meters (56 ft) wide, and 42.5 meters (139 ft) high, ranking in size with the new Gothic cathedrals in France. [1]

In addition to serving as a place of worship, the Sainte-Chapelle played an important role in the political and cultural ambitions of King Louis and his successors.[2][3] With the imperial throne at Constantinople occupied by a mere Count of Flanders and with the Holy Roman Empire in uneasy disarray, Louis' artistic and architectural patronage helped to position him as the central monarch of western Christendom, the Sainte-Chapelle fitting into a long tradition of prestigious palace chapels. Just as the Emperor could pass privately from his palace into the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, so now Louis could pass directly from his palace into the Sainte-Chapelle. More importantly, the two-story palace chapel had obvious similarities to Charlemagne's palatine chapel at Aachen (built 782–805)—a parallel that Louis was keen to exploit in presenting himself as a worthy successor to the first Holy Roman Emperor.[4] The presence of the fragment of the True Cross and crown of thorns gave enormous prestige to Louis IX. Pope Innocent IV proclaimed that it meant that Christ had symbolically crowned Louis with his own crown.[5]

The Royal Chapel

Sainte-Chapelle, in the courtyard of the royal palace on the Île de la Cité (now part of a later administrative complex known as La Conciergerie), was built to house Louis IX's collection of relics of Christ, which included the crown of thorns, the Image of Edessa, and some thirty other items. Louis purchased his Passion relics from Baldwin II, the Latin emperor at Constantinople, for the sum of 135,000 livres. This money was paid to the Venetians to whom the relics had been pawned.

The relics arrived in Paris in August 1239, carried from Venice by two Dominican friars. Upon arrival, King Louis hosted a week-long celebratory reception for the relics. For the final stage of their journey they were carried by Louis IX himself, barefoot and dressed as a penitent, a scene depicted in the Relics of the Passion window on the south side of the chapel. The relics were stored in a large and elaborate silver chest, the Grand-Chasse, on which Louis spent a further 100,000 livres.

The entire chapel, by contrast, cost 40,000 livres to build and glaze. Until it was completed in 1248, the relics were housed at chapels at the Château de Vincennes and a specially built chapel at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In 1246, fragments of the True Cross and the Holy Lance were added to Louis's collection, along with other relics. The chapel was consecrated on 26 April 1248 and Louis's relics were moved to their new home with great ceremony. Shortly afterward, the King departed on the Seventh Crusade, in which he was captured and later ransomed and released.[1] In 1704, the French composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier was buried in the chapel's small cemetery, but this cemetery no longer exists.

The Parisian scholastic Jean de Jandun praised the building as one of Paris' most beautiful structures in his "Tractatus de laudibus Parisius" (1323), citing:

that most beautiful of chapels, the chapel of the king, most decently situated within the walls of the king's house, enjoys a complete and indissoluble structure of the most solid stone. The most excellent colors of the pictures, the precious gilding of the images, the beautiful transparence of the ruddy windows on all sides, the most beautiful cloths of the altars, the wondrous merits of the sanctuary, the figures of the reliquaries externally adorned with dazzling gems, bestow such a hyperbolic beauty on that house of prayer, that, in going into it below, one understandably believes oneself, as if rapt to heaven, to enter one of the best chambers of Paradise.

O how salutary prayers to the all-powerful God pour out in these oratories, when the internal and spiritual purities of those praying correspond proportionally with the external and physical elegance of the oratory!

O how peacefully to the most holy God the praises are sung in these tabernacles, when the hearts of those singers are by the pleasing pictures of the tabernacle analogically beautified with the virtues!

O how acceptable to the most glorious God appear the offerings on these altars, when the life of those sacrificing shines in correspondence with the gilded light of the altars![6]

Modifications (16th–18th century)

The chapel underwent considerable modification in the centuries that followed. A new two-story building, the Treasury of Chartres, was attached to the chapel on the north side shortly after it was completed. It remained until 1783, when it was demolished to build the new Palace of Justice. Another building, which served as a vestiary and sacristy, as well as residence for the guardian of the treasury, was placed on the north side. In the 15th century, Louis X of France built a monumental enclosed stairway from the courtyard on the south side to the upper level. This was damaged by fire in 1630, rebuilt, but finally demolished. Fires in the palace in 1630 and 1776 also caused considerable damage, especially to the furniture, and a flood in the winter of 1689–1690 caused major damage to the painted walls of the lower chapel. The original stained glass on the ground floor was removed, and the floor raised. The original ground floor glass was replaced by Gothic-style windows in the 19th century.[7]

Revolutionary vandalism (18th century)Sainte-Chapelle, as both a symbol of religion and royalty, was a prime target for vandalism during the French Revolution. The chapel was turned into a storehouse for grain, and the sculpture and royal emblems on the exterior were smashed.[8] The spire was pulled down. Some of the stained glass was broken or dispersed, but nearly two-thirds of the glass today is original; some of the original glass was relocated in other windows, The sacred relics were dispersed although some survive as the "relics of Sainte-Chapelle" in the treasury of Notre-Dame de Paris. Various reliquaries, including the grande châsse, were melted down for their precious metal.

Restoration (19th–21st century)

Between 1803 and 1837, the upper chapel was turned into a depository for the archives of the Palace of Justice next door.[9] The lower two meters (6 ft 7 in) of stained glass was removed to facilitate working light. Some of the glass was used to replace broken glass in other windows, and other panes were put on the market.[10] Beginning in 1835, scholars, archeologists and writers demanded that the church be preserved and restored to its medieval state. In 1840, under King Louis-Philippe, a long campaign of restoration began. It was first conducted by Félix Duban, then by Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Émile Boeswillwald, with the young Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as an assistant. The work continued for twenty-eight years, and served as a training ground for a generation of archeologists and restorers.[9] It was faithful to the original drawings and descriptions of the chapel that survived.[11]

The restoration of the stained glass was a parallel project, which lasted from 1846 until 1855, with the goal of returning the chapel to its original appearance. It was carried out by the glass craftsmen Antoine Lusson and Maréchal de Metz and the designer Louis Steinheil. About one third of the glass, added in later years, was removed and replaced with medieval glass from other sources, or with new glass made in the original Gothic style. Eighteen of the original panels are found today in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.[12]

The stained glass was removed and placed into safe storage during World War II. In 1945 a layer of external varnish had been applied to protect the glass from the dust and scratches of wartime bombing.[13] This had gradually darkened, making the already fading images even harder to see.[14] In 2008, a more comprehensive seven-year programme of restoration began, costing some €10 million to clean and preserve all the stained glass, clean the facade stonework and conserve and repair some of the sculptures. Half of the funding was provided by private donors, the other half coming from the Villum Foundation.[13] Included in the restoration was an innovative thermoformed glass layer applied outside the stained-glass windows for added protection. The restoration of the flamboyant rose window on the west facade was completed in 2015 in time for the 800th anniversary of the birth of St. Louis.[15]

Add new comment