The Mona Lisa ( MOH-nə LEE-sə; Italian: Gioconda [dʒoˈkonda] or Monna Lisa [ˈmɔnna ˈliːza]; French: Joconde [ʒɔkɔ̃d]) is a half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described as "the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, [and] the most parodied work of art in the world". The painting's novel qualities include the subject's enigmatic expression, monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism.

The painting has been traditionally considered to depict the I...Read more

The Mona Lisa ( MOH-nə LEE-sə; Italian: Gioconda [dʒoˈkonda] or Monna Lisa [ˈmɔnna ˈliːza]; French: Joconde [ʒɔkɔ̃d]) is a half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described as "the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, [and] the most parodied work of art in the world". The painting's novel qualities include the subject's enigmatic expression, monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism.

The painting has been traditionally considered to depict the Italian noblewoman Lisa del Giocondo. It is painted in oil on a white Lombardy poplar panel. Leonardo never gave the painting to the Giocondo family. It was believed to have been painted between 1503 and 1506; however, Leonardo may have continued working on it as late as 1517. It was acquired by King Francis I of France and is now the property of the French Republic. It has normally been on display at the Louvre in Paris since 1797.

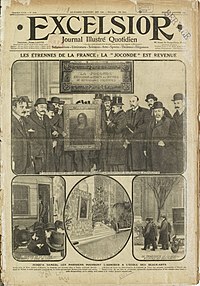

The painting's global fame and popularity partly stem from its 1911 theft by Vincenzo Peruggia, who attributed his actions to Italian patriotism—a belief it should belong to Italy. The theft and subsequent recovery in 1914 generated unprecedented publicity for an art theft, and led to the publication of many cultural depictions such as the 1915 opera Mona Lisa, two early 1930s films (The Theft of the Mona Lisa and Arsène Lupin) and the song "Mona Lisa" recorded by Nat King Cole—one of the most successful songs of the 1950s.

The Mona Lisa is one of the most valuable paintings in the world. It holds the Guinness World Record for the highest known painting insurance valuation in history at US$100 million in 1962, equivalent to $1 billion as of 2023.

Of Leonardo da Vinci's works, the Mona Lisa is the only portrait whose authenticity has never been seriously questioned,[1] and one of four works – the others being Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, Adoration of the Magi and The Last Supper – whose attribution has avoided controversy.[2] He had begun working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model of the Mona Lisa, by October 1503.[3][4] It is believed by some that the Mona Lisa was begun in 1503 or 1504 in Florence.[5] Although the Louvre states that it was "doubtless painted between 1503 and 1506",[6] art historian Martin Kemp says that there are some difficulties in confirming the dates with certainty.[7] Alessandro Vezzosi believes that the painting is characteristic of Leonardo's style in the final years of his life, post-1513.[8] Other academics argue that, given the historical documentation, Leonardo would have painted the work from 1513.[9] According to Vasari, "after he had lingered over it four years, [he] left it unfinished".[10] In 1516, Leonardo was invited by King Francis I to work at the Clos Lucé near the Château d'Amboise; it is believed that he took the Mona Lisa with him and continued to work on it after he moved to France.[11] Art historian Carmen C. Bambach has concluded that Leonardo probably continued refining the work until 1516 or 1517.[12] Leonardo's right hand was paralytic c. 1517,[13] which may indicate why he left the Mona Lisa unfinished.[14][15][16][a]

Raphael's drawing (c. 1505), after Leonardo; today in the Louvre along with the Mona Lisa[18]

Raphael's drawing (c. 1505), after Leonardo; today in the Louvre along with the Mona Lisa[18]c. 1505,[18] Raphael executed a pen-and-ink sketch, in which the columns flanking the subject are more apparent. Experts universally agree that it is based on Leonardo's portrait.[19][20][21] Other later copies of the Mona Lisa, such as those in the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design and The Walters Art Museum, also display large flanking columns. As a result, it was thought that the Mona Lisa had been trimmed.[22][23][24][25] However, by 1993, Frank Zöllner observed that the painting surface had never been trimmed;[26] this was confirmed through a series of tests in 2004.[27] In view of this, Vincent Delieuvin, curator of 16th-century Italian painting at the Louvre, states that the sketch and these other copies must have been inspired by another version,[28] while Zöllner states that the sketch may be after another Leonardo portrait of the same subject.[26]

The record of an October 1517 visit by Louis d'Aragon states that the Mona Lisa was executed for the deceased Giuliano de' Medici, Leonardo's steward at Belvedere, Vienna, between 1513 and 1516[29][30][b]—but this was likely an error.[31][c] According to Vasari, the painting was created for the model's husband, Francesco del Giocondo.[32] A number of experts have argued that Leonardo made two versions (because of the uncertainty concerning its dating and commissioner, as well as its fate following Leonardo's death in 1519, and the difference of details in Raphael's sketch—which may be explained by the possibility that he made the sketch from memory).[18][21][20][33] The hypothetical first portrait, displaying prominent columns, would have been commissioned by Giocondo c. 1503, and left unfinished in Leonardo's pupil and assistant Salaì's possession until his death in 1524. The second, commissioned by Giuliano de' Medici c. 1513, would have been sold by Salaì to Francis I in 1518[d] and is the one in the Louvre today.[21][20][33][34] Others believe that there was only one true Mona Lisa but are divided as to the two aforementioned fates.[7][35][36] At some point in the 16th century, a varnish was applied to the painting.[37] It was kept at the Palace of Fontainebleau until Louis XIV moved it to the Palace of Versailles, where it remained until the French Revolution.[38] In 1797, it went on permanent display at the Louvre.[39]

Refuge, theft, and vandalism Louis Béroud's 1911 painting depicting Mona Lisa displayed in the Louvre before the theft, which Béroud discovered and reported to the guards

Louis Béroud's 1911 painting depicting Mona Lisa displayed in the Louvre before the theft, which Béroud discovered and reported to the guardsAfter the French Revolution, the painting was moved to the Louvre, but spent a brief period in the bedroom of Napoleon (d. 1821) in the Tuileries Palace.[38] The Mona Lisa was not widely known outside the art world, but in the 1860s, a portion of the French intelligentsia began to hail it as a masterwork of Renaissance painting.[40] During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), the painting was moved from the Louvre to the Brest Arsenal.[41]

In 1911, the painting was still not popular among the lay-public.[42] On 21 August 1911, the painting was stolen from the Louvre.[43] The painting was first missed the next day by painter Louis Béroud. After some confusion as to whether the painting was being photographed somewhere, the Louvre was closed for a week for investigation. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire came under suspicion and was arrested and imprisoned. Apollinaire implicated his friend Pablo Picasso, who was brought in for questioning. Both were later exonerated.[44][45] The real culprit was Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia, who had helped construct the painting's glass case.[46] He carried out the theft by entering the building during regular hours, hiding in a broom closet, and walking out with the painting hidden under his coat after the museum had closed.[47]

Peruggia was an Italian patriot who believed that Leonardo's painting should have been returned to an Italian museum.[48] Peruggia may have been motivated by an associate whose copies of the original would significantly rise in value after the painting's theft.[49] After having kept the Mona Lisa in his apartment for two years, Peruggia grew impatient and was caught when he attempted to sell it to Giovanni Poggi, director of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It was exhibited in the Uffizi Gallery for over two weeks and returned to the Louvre on 4 January 1914.[50] Peruggia served six months in prison for the crime and was hailed for his patriotism in Italy.[45] A year after the theft, Saturday Evening Post journalist Karl Decker wrote that he met an alleged accomplice named Eduardo de Valfierno, who claimed to have masterminded the theft. Forger Yves Chaudron was to have created six copies of the painting to sell in the US while concealing the location of the original.[49] Decker published this account of the theft in 1932.[51][52]

During World War II, it was again removed from the Louvre and taken first to the Château d'Amboise, then to the Loc-Dieu Abbey and Château de Chambord, then finally to the Musée Ingres in Montauban.[52][53]

In 1956, a vandal threw acid at the Mona Lisa while it was on a temporary exhibition in Montauban, hitting its lower portion.[54] Later that year, on 30 December 1956, Bolivian Ugo Ungaza Villegas threw a rock at the Mona Lisa while it was on display at the Louvre. He did so with such force that it shattered the glass case and dislodged a speck of pigment near the left elbow.[55] The painting was protected by glass because a few years earlier a man who claimed to be in love with the painting had cut it with a razor blade and tried to steal it.[56] Since then, bulletproof glass has been used to shield the painting from any further attacks. Subsequently, on 21 April 1974, while the painting was on display at the Tokyo National Museum, a woman sprayed it with red paint as a protest against that museum's failure to provide access for disabled people.[57] On 2 August 2009, a Russian woman, distraught over being denied French citizenship, threw a ceramic teacup purchased at the Louvre; the vessel shattered against the glass enclosure.[58][59] In both cases, the painting was undamaged.

In recent decades, the painting has been temporarily moved to accommodate renovations to the Louvre on three occasions: between 1992 and 1995, from 2001 to 2005, and again in 2019.[60] A new queuing system introduced in 2019 reduces the amount of time museum visitors have to wait in line to see the painting. After going through the queue, a group has about 30 seconds to see the painting.[61]

On 29 May 2022, a male activist, disguised as a woman in a wheelchair, threw cake at the protective glass covering the painting in an apparent attempt to raise awareness for climate change.[62] The painting was not damaged.[63] The man was arrested and placed in psychiatric care in the police headquarters.[64] An investigation was opened after the Louvre filed a complaint.[65] On 28 January 2024, two attackers from the environmentalist group Riposte Alimentaire (Food Retaliation) threw soup at the painting's protective glass, demanding the right to "healthy and sustainable food" and criticizing the contemporary state of agriculture.[66]

Modern analysisIn the early 21st century, French scientist Pascal Cotte hypothesized a hidden portrait underneath the surface of the painting. He analyzed the painting in the Louvre with reflective light technology beginning in 2004, and produced circumstantial evidence for his theory.[67][68][69] Cotte admits that his investigation was carried out only in support of his hypotheses and should not be considered as definitive proof.[68][35] The underlying portrait appears to be of a model looking to the side, and lacks flanking columns,[70] but does not fit with historical descriptions of the painting. Both Vasari and Gian Paolo Lomazzo describe the subject as smiling,[71][72] unlike the subject in Cotte's supposed portrait.[68][35] In 2020, Cotte published a study alleging that the painting has an underdrawing, transferred from a preparatory drawing via the spolvero technique.[73]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment