Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁ(ə) dam də paʁi] ; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. The cathedral, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is considered one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture. Several attributes set it apart from the earlier Romanesque style, particularly its pioneering use of the rib vault and flying buttress, its enormous and colourful rose windows, and the naturalism and abundance of its sculptural decoration. Notre-Dame also stands out for its three pipe organs (one historic) and its immense church bells.

Built during medieval France, construction of the cathedral began in 1163 under Bishop Maurice de Sully and was largely completed by 126...Read more

Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁ(ə) dam də paʁi] ; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. The cathedral, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is considered one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture. Several attributes set it apart from the earlier Romanesque style, particularly its pioneering use of the rib vault and flying buttress, its enormous and colourful rose windows, and the naturalism and abundance of its sculptural decoration. Notre-Dame also stands out for its three pipe organs (one historic) and its immense church bells.

Built during medieval France, construction of the cathedral began in 1163 under Bishop Maurice de Sully and was largely completed by 1260, though it was modified in succeeding centuries. In the 1790s, during the French Revolution, Notre-Dame suffered extensive desecration; much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. In the 19th century, the coronation of Napoleon and the funerals of many of the French Republic's presidents took place at the cathedral. The 1831 publication of Victor Hugo's novel Notre-Dame de Paris (in English: The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) inspired interest which led to restoration between 1844 and 1864, supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. On 26 August 1944, the Liberation of Paris from German occupation was celebrated in Notre-Dame with the singing of the Magnificat. Beginning in 1963, the cathedral's façade was cleaned of soot and grime. Another cleaning and restoration project was carried out between 1991 and 2000.

The cathedral is a widely recognized symbol of the city of Paris and the French nation. In 1805, it was awarded honorary status as a minor basilica. As the cathedral of the archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the archbishop of Paris (currently Laurent Ulrich). In the early 21st century, approximately 12 million people visited Notre-Dame annually, making it the most visited monument in Paris. The cathedral is renowned for its Lent sermons, a tradition founded in the 1830s by the Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire. These sermons have increasingly been given by leading public figures or government-employed academics.

Over time, the cathedral has gradually been stripped of many decorations and artworks. However, the cathedral still contains Gothic, Baroque, and 19th-century sculptures, 17th- and early 18th-century altarpieces, and some of the most important relics in Christendom – including the Crown of Thorns, and a sliver and nail from the True Cross.

On 15 April 2019, while Notre-Dame was undergoing renovation and restoration, its roof caught fire and burned for 15 hours. The cathedral sustained serious damage. The flèche (the timber spirelet over the crossing) was destroyed, as was most of the lead-covered wooden roof above the stone vaulted ceiling. This contaminated the site and nearby environment with lead. Restoration proposals suggested modernizing the cathedral, but the French National Assembly rejected them, enacting a law in July 2019 that required the restoration preserve the cathedral's "historic, artistic and architectural interest". The task of stabilizing the building against potential collapse was completed in November 2020. The cathedral is expected to reopen on 8 December 2024; the date was confirmed by President Macron.

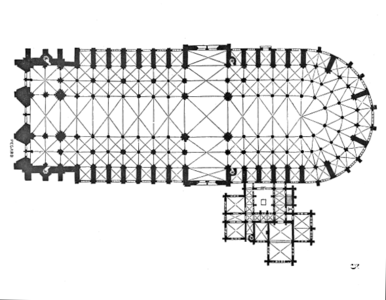

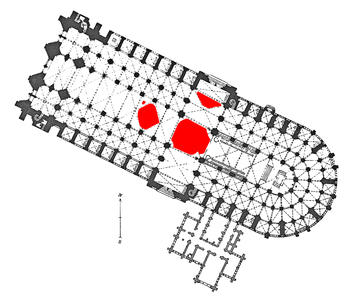

Outline of the primitive Cathedral of Notre-Dame in 1150, on the spot of the nave, the transept and the choir of the current building. The Cathedral of Saint Étienne was located to the west, at the level of today's parvis.Construction sequence from 12th century to present-day, created by Stephen Murray and Myles Zhang

Outline of the primitive Cathedral of Notre-Dame in 1150, on the spot of the nave, the transept and the choir of the current building. The Cathedral of Saint Étienne was located to the west, at the level of today's parvis.Construction sequence from 12th century to present-day, created by Stephen Murray and Myles ZhangIt is believed that before the arrival of Christianity in France, a Gallo-Roman temple dedicated to Jupiter stood on the site of Notre-Dame. Evidence for this includes the Pillar of the Boatmen, discovered beneath the cathedral in 1710. In the 4th or 5th century, a large early Christian church, the Cathedral of Saint Étienne, was built on the site, close to the royal palace.[1] The entrance was situated about 40 metres (130 ft) west of the present west front of Notre-Dame, and the apse was located about where the west façade is today. It was roughly half the size of the later Notre-Dame, 70 metres (230 ft) long—and separated into nave and four aisles by marble columns, then decorated with mosaics.[2][3]

The last church before the cathedral of Notre-Dame was a Romanesque remodeling of Saint-Étienne that, although enlarged and remodeled, was found to be unfit for the growing population of Paris.[4][a] A baptistery, the Church of Saint-John-le-Rond, built about 452, was located on the north side of the west front of Notre-Dame until the work of Jacques-Germain Soufflot in the 18th century.[6]

In 1160, the Bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully,[6] decided to build a new and much larger church. He summarily demolished the earlier cathedral and recycled its materials.[4] Sully decided that the new church should be built in the Gothic style, which had been inaugurated at the royal abbey of Saint Denis in the late 1130s.[3]

ConstructionThe chronicler Jean de Saint-Victor recorded in the Memorial Historiarum that the construction of Notre-Dame began between 24 March and 25 April 1163 with the laying of the cornerstone in the presence of King Louis VII and Pope Alexander III.[7][8] Four phases of construction took place under bishops Maurice de Sully and Eudes de Sully (not related to Maurice), according to masters whose names have been lost. Analysis of vault stones that fell in the 2019 fire shows that they were quarried in Vexin, a county northwest of Paris, and presumably brought up the Seine by ferry.[9]

Cross-section of the double supporting arches and buttresses of the nave, drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as they would have appeared from 1220 to 1230.[10]

Cross-section of the double supporting arches and buttresses of the nave, drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as they would have appeared from 1220 to 1230.[10]The first phase began with the construction of the choir and its two ambulatories. According to Robert of Torigni, the choir was completed in 1177 and the high altar consecrated on 19 May 1182 by Cardinal Henri de Château-Marçay, the Papal legate in Paris, and Maurice de Sully.[11][failed verification] The second phase, from 1182 to 1190, concerned the construction of the four sections of the nave behind the choir and its aisles to the height of the clerestories. It began after the completion of the choir but ended before the final allotted section of the nave was finished. Beginning in 1190, the bases of the façade were put in place, and the first traverses were completed.[2] Heraclius of Caesarea called for the Third Crusade in 1185 from the still-incomplete cathedral.

Louis IX deposited the relics of the passion of Christ, which included the Crown of thorns, a nail from the Cross and a sliver of the Cross, which he had purchased at great expense from the Latin Emperor Baldwin II, in the cathedral during the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle. An under-shirt, believed to have belonged to Louis, was added to the collection of relics at some time after his death.

Transepts were added at the choir, where the altar was located, in order to bring more light into the centre of the church. The use of simpler four-part rather than six-part rib vaults meant that the roofs were stronger and could be higher. After Bishop Maurice de Sully's death in 1196, his successor, Eudes de Sully oversaw the completion of the transepts, and continued work on the nave, which was nearing completion at the time of his death in 1208. By this time, the western façade was already largely built, though it was not completed until around the mid-1240s. Between 1225 and 1250 the upper gallery of the nave was constructed, along with the two towers on the west façade.[12]

Arrows show forces in vault and current flying buttresses (detailed description).

Arrows show forces in vault and current flying buttresses (detailed description).Another significant change came in the mid-13th century, when the transepts were remodelled in the latest Rayonnant style; in the late 1240s Jean de Chelles added a gabled portal to the north transept topped by a spectacular rose window. Shortly afterward (from 1258) Pierre de Montreuil executed a similar scheme on the southern transept. Both these transept portals were richly embellished with sculpture; the south portal depicts scenes from the lives of Saint Stephen and of various local saints, while the north portal featured the infancy of Christ and the story of Theophilus in the tympanum, with a highly influential statue of the Virgin and Child in the trumeau.[13][12] Master builders Pierre de Chelles, Jean Ravy, Jean le Bouteiller, and Raymond du Temple succeeded de Chelles and de Montreuil and then each other in the construction of the cathedral. Ravy completed de Chelles's rood screen and chevet chapels, then began the 15-metre (49 ft) flying buttresses of the choir. Jean le Bouteiller, Ravy's nephew, succeeded him in 1344 and was himself replaced on his death in 1363 by his deputy, Raymond du Temple.

Philip the Fair opened the first Estates General in the cathedral in 1302.

An important innovation in the 13th century was the introduction of the flying buttress. Before the buttresses, all of the weight of the roof pressed outward and down to the walls, and the abutments supporting them. With the flying buttress, the weight was carried by the ribs of the vault entirely outside the structure to a series of counter-supports, which were topped with stone pinnacles which gave them greater weight. The buttresses meant that the walls could be higher and thinner, and could have larger windows. The date of the first buttresses is not known with precision beyond an installation date in the 13th century. Art historian Andrew Tallon, however, has argued, based on detailed laser scans of the entire structure, that the buttresses were part of the original design. According to Tallon, the scans indicate that "the upper part of the building has not moved one smidgen in 800 years,"[14] whereas if they were added later some movement from prior to their addition would be expected. Tallon thus concluded that flying buttresses were present from the outset.[14] The first buttresses were replaced by larger and stronger ones in the 14th century; these had a reach of fifteen metres (50') between the walls and counter-supports.[2]

John of Jandun recognized the cathedral as one of Paris's three most important buildings [prominent structures] in his 1323 Treatise on the Praises of Paris:

That most glorious church of the most glorious Virgin Mary, mother of God, deservedly shines out, like the sun among stars. And although some speakers, by their own free judgment, because [they are] able to see only a few things easily, may say that some other is more beautiful, I believe, however, respectfully, that, if they attend more diligently to the whole and the parts, they will quickly retract this opinion. Where indeed, I ask, would they find two towers of such magnificence and perfection, so high, so large, so strong, clothed round about with such multiple varieties of ornaments? Where, I ask, would they find such a multipartite arrangement of so many lateral vaults, above and below? Where, I ask, would they find such light-filled amenities as the many surrounding chapels? Furthermore, let them tell me in what church I may see such a large cross, of which one arm separates the choir from the nave. Finally, I would willingly learn where [there are] two such circles, situated opposite each other in a straight line, which on account of their appearance are given the name of the fourth vowel [O]; among which smaller orbs and circles, with wondrous artifice, so that some arranged circularly, others angularly, surround windows ruddy with precious colours and beautiful with the most subtle figures of the pictures. In fact, I believe that this church offers the carefully discerning such cause for admiration that its inspection can scarcely sate the soul.

On 16 December 1431, the boy-king Henry VI of England was crowned king of France in Notre-Dame, aged ten, the traditional coronation church of Reims Cathedral being under French control.[16]

During the Renaissance, the Gothic style fell out of style, and the internal pillars and walls of Notre-Dame were covered with tapestries.[17]

In 1548, rioting Huguenots damaged some of the statues of Notre-Dame, considering them idolatrous.[18]

The fountain in Notre-Dame's parvis was added in 1625 to provide nearby Parisians with running water.[19]

Since 1449, the Parisian goldsmith guild had made regular donations to the cathedral chapter. In 1630, the guild began donating a large altarpiece every year on the first of May. These works came to be known as the grands mays.[20] The subject matter was restricted to episodes from the Acts of the Apostles. The prestigious commission was awarded to the most prominent painters and, after 1648, members of the Académie Royale.

Seventy-six paintings had been donated by 1708, when the custom was discontinued for financial reasons. Those works were confiscated in 1793 and the majority were subsequently dispersed among regional museums in France. Those that remained in the cathedral were removed or relocated within the building by the 19th-century restorers.

Today, thirteen of the grands mays hang in Notre-Dame although these paintings suffered water damage during the fire of 2019 and were removed for conservation.

An altarpiece depicting the Visitation, painted by Jean Jouvenet in 1707, was also located in the cathedral.

The canon Antoine de La Porte commissioned for Louis XIV six paintings depicting the life of the Virgin Mary for the choir. At this same time, Charles de La Fosse painted his Adoration of the Magi, now in the Louvre.[21] Louis Antoine de Noailles, archbishop of Paris, extensively modified the roof of Notre-Dame in 1726, renovating its framing and removing the gargoyles with lead gutters. Noailles also strengthened the buttresses, galleries, terraces, and vaults.[22] In 1756, the cathedral's canons decided that its interior was too dark. The medieval stained glass windows, except the rosettes, were removed and replaced with plain, white glass panes.[17] Lastly, Jacques-Germain Soufflot was tasked with the modification of the portals at the front of the cathedral to allow processions to enter more easily.

After the French Revolution in 1789, Notre-Dame and the rest of the church's property in France was seized and made public property.[23] The cathedral was rededicated in 1793 to the Cult of Reason, and then to the Cult of the Supreme Being in 1794.[24] During this time, many of the treasures of the cathedral were either destroyed or plundered. The twenty-eight statues of biblical kings located at the west façade, mistaken for statues of French kings, were beheaded.[2][25] Many of the heads were found during a 1977 excavation nearby, and are on display at the Musée de Cluny. For a time the Goddess of Liberty replaced the Virgin Mary on several altars.[26] The cathedral's great bells escaped being melted down. All of the other large statues on the façade, with the exception of the statue of the Virgin Mary on the portal of the cloister, were destroyed.[2] The cathedral came to be used as a warehouse for the storage of food and other non-religious purposes.[18]

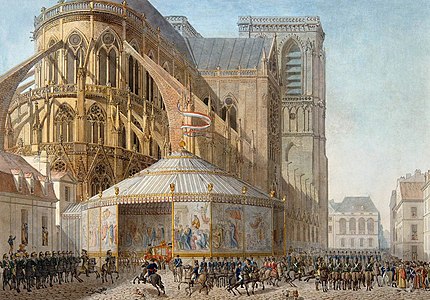

With the Concordat of 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte restored Notre-Dame to the Catholic Church, though this was only finalized on 18 April 1802. Napoleon also named Paris's new bishop, Jean-Baptiste de Belloy, who restored the cathedral's interior. Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine made quasi-Gothic modifications to Notre-Dame for the coronation of Napoleon as Emperor of the French within the cathedral. The building's exterior was whitewashed and the interior decorated in Neoclassical style, then in vogue.[27]

In the decades after the Napoleonic Wars, Notre-Dame fell into such a state of disrepair that Paris officials considered its demolition. Victor Hugo, who admired the cathedral, wrote the novel Notre-Dame de Paris (published in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) in 1831 to save Notre-Dame. The book was an enormous success, raising awareness of the cathedral's decaying state.[2] The same year as Hugo's novel was published, however, anti-Legitimists plundered Notre-Dame's sacristy.[28] In 1844 King Louis Philippe ordered that the church be restored.[2]

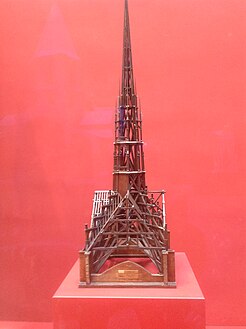

The architect who had hitherto been in charge of Notre-Dame's maintenance, Étienne-Hippolyte Godde, was dismissed. In his stead, Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who had distinguished themselves with the restoration of the nearby Sainte-Chapelle, were appointed in 1844. The next year, Viollet-le-Duc submitted a budget of 3,888,500 francs, which was reduced to 2,650,000 francs, for the restoration of Notre-Dame and the construction of a new sacristy building. This budget was exhausted in 1850, and work stopped as Viollet-le-Duc made proposals for more money. In totality, the restoration cost over 12 million francs. Supervising a large team of sculptors, glass makers and other craftsmen, and working from drawings or engravings, Viollet-le-Duc remade or added decorations if he felt they were in the spirit of the original style. One of the latter items was a taller and more ornate flèche, to replace the original 13th-century flèche, which had been removed in 1786.[29] The decoration of the restoration included a bronze roof statue of Saint Thomas that resembles Viollet-le-Duc, as well as the sculpture of mythical creatures on the Galerie des Chimères.[18]

The construction of the sacristy was especially financially costly. To secure a firm foundation, it was necessary for Viollet-le-Duc's labourers to dig 9 metres (30 ft). Master glassworkers meticulously copied styles of the 13th century, as written about by art historians Antoine Lusson and Adolphe Napoléon Didron.[30]

During the Paris Commune of March through May 1871, the cathedral and other churches were closed, and some two hundred priests and the Archbishop of Paris were taken as hostages. In May, during the Semaine sanglante of "Bloody Week", as the army recaptured the city, the Communards targeted the cathedral, along with the Tuileries Palace and other landmarks, for destruction; the Communards piled the furniture together in order to burn the cathedral. The arson was halted when the Communard government realised that the fire would also destroy the neighbouring Hôtel-Dieu hospital, filled with hundreds of patients.[31]

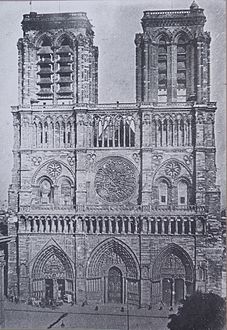

Façade of Notre-Dame in the 1930s

Façade of Notre-Dame in the 1930sDuring the liberation of Paris in August 1944, the cathedral suffered some minor damage from stray bullets. Some of the medieval glass was damaged, and was replaced by glass with modern abstract designs. On 26 August, a special Mass was held in the cathedral to celebrate the liberation of Paris from the Germans; it was attended by General Charles De Gaulle and General Philippe Leclerc.

In 1963, on the initiative of culture minister André Malraux and to mark the 800th anniversary of the cathedral, the façade was cleaned of the centuries of soot and grime, restoring it to its original off-white colour.[32]

On 19 January 1969, vandals placed a North Vietnamese flag at the top the flèche, and sabotaged the stairway leading to it. The flag was cut from the flèche by Paris Fire Brigade Sergeant Raymond Belle in a daring helicopter mission, the first of its kind in France.[33][34][35]

The Requiem Mass of Charles de Gaulle was held in Notre-Dame on 12 November 1970.[36] The next year, on 26 June 1971, Philippe Petit walked across a tight-rope strung between Notre-Dame's two bell towers entertaining spectators.[37]

After the Magnificat of 30 May 1980, Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass on the parvis of the cathedral.[38]

The Requiem Mass of François Mitterrand was held at the cathedral, as with past French heads of state, on 11 January 1996.[39]

The stone masonry of the cathedral's exterior had deteriorated in the 19th and 20th century due to increased air pollution in Paris, which accelerated erosion of decorations and discoloured the stone. By the late 1980s, several gargoyles and turrets had also fallen or become too loose to safely remain in place.[40] A decade-long renovation programme began in 1991 and replaced much of the exterior, with care given to retain the authentic architectural elements of the cathedral, including rigorous inspection of new limestone blocks.[40][41] A discreet system of electrical wires, not visible from below, was also installed on the roof to deter pigeons.[42] The cathedral's pipe organ was upgraded with a computerized system to control the mechanical connections to the pipes.[43] The west face was cleaned and restored in time for millennium celebrations in December 1999.[44]

21st century Notre-Dame in May 2012. From top to bottom, nave walls are pierced by clerestory windows, arches to triforium, and arches to side aisles.

Notre-Dame in May 2012. From top to bottom, nave walls are pierced by clerestory windows, arches to triforium, and arches to side aisles.The Requiem Mass of Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, former archbishop of Paris and Jewish convert to Catholicism, was held in Notre-Dame on 10 August 2007.[45]

The set of four 19th-century bells at the top of the northern towers at Notre-Dame were melted down and recast into new bronze bells in 2013, to celebrate the building's 850th anniversary. They were designed to recreate the sound of the cathedral's original bells from the 17th century.[46][47] Despite the 1990s renovation, the cathedral had continued to show signs of deterioration that prompted the national government to propose a new renovation program in the late 2010s.[48][49] The entire renovation was estimated to cost €100 million, which the archbishop of Paris planned to raise through funds from the national government and private donations.[50] A €6 million renovation of the cathedral's flèche began in late 2018 and continued into the following year, requiring the temporary removal of copper statues on the roof and other decorative elements days before the April 2019 fire.[51][52]

Notre-Dame began a year-long celebration of the 850th anniversary of the laying of the first building block for the cathedral on 12 December 2012.[53] During that anniversary year, on 21 May 2013, Dominique Venner, a historian and white nationalist, placed a letter on the church altar and shot himself, dying instantly. Around 1,500 visitors were evacuated from the cathedral.[54]

French police arrested two people on 8 September 2016 after a car containing seven gasoline canisters was found near Notre-Dame.[55]

On 10 February 2017, French police arrested four persons in Montpellier already known by authorities to have ties to radical Islamist organizations on charges of plotting to travel to Paris and attack the cathedral.[56] Later that year, on 6 June, visitors were shut inside Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris after a man with a hammer attacked a police officer outside.[57][58]

2019 fireOn 15 April 2019 the cathedral caught fire, destroying the flèche and the "forest" of oak roof beams supporting the lead roof.[59][60][61] It was speculated that the fire was linked to ongoing renovation work.

According to later studies, the fire broke out in the attic of the cathedral at 18:18. The smoke detectors immediately signaled the fire to a cathedral employee, who did not summon the fire brigade but instead sent a cathedral guard to investigate. Instead of going to the correct attic, the guard was sent to the wrong location, to the attic of the adjoining sacristy, and reported there was no fire. The guard telephoned his supervisor, who did not immediately answer. About fifteen minutes later the error was discovered, whereupon the guard's supervisor told him to go to the correct location. The fire brigade was still not notified. By the time the guard had climbed the three hundred steps to the cathedral attic the fire was well advanced.[62] The alarm system was not designed to automatically notify the fire brigade, which was finally summoned at 18:51 after the guard had returned from the attic and reported a now-raging fire, and more than half an hour after the fire alarm had begun sounding.[63]

Firefighters arrived in less than ten minutes.[64]

The cathedral's flèche collapsed at 19:50, bringing down some 750 tonnes of stone and lead. The firefighters inside were ordered back down. By this time the fire had spread to the north tower, where the eight bells were located. The firefighters concentrated their efforts in the tower. They feared that, if the bells fell, they could wreck the tower, and endanger the structure of the other tower and the whole cathedral. They had to ascend a stairway threatened by fire, and to contend with low water pressure for their hoses. As other firefighters watered the stairway and the roof, a team of twenty climbed the narrow stairway of the south tower, crossed to the north tower, lowered hoses to be connected to fire engines outside the cathedral, and sprayed water on the fire beneath the bells. By 21:45, they brought the fire under control.[62]

The main structure was intact; firefighters saved the façade, towers, walls, buttresses, and stained glass windows. The Great Organ, which has over 8,000 pipes and was built by François Thierry in the 18th century was also saved but sustained water damage.[65] Because of the ongoing renovation, the copper statues on the flèche had been removed before the fire.[66] The stone vaulting that forms the ceiling of the cathedral had several holes but was otherwise intact.[67]

Since 1905, France's cathedrals (including Notre-Dame) have been owned by the state, which is self-insured. Some costs might be recovered through insurance coverage if the fire is found to have been caused by contractors working on the site.[68] The French insurer AXA provided insurance coverage for two of the contracting firms working on Notre-Dame's restoration before the blaze. AXA also provided insurance coverage for some of the relics and artworks in the cathedral.[69]

President Emmanuel Macron said approximately 500 firefighters helped to battle the fire. One firefighter was seriously injured and two police officers were hurt during the blaze.[70]

An ornate tapestry woven in the early 1800s is going on public display for only the third time in recent decades. The decoration was rescued from Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral after the fire.[71]

For the first time in more than 200 years, the Christmas Mass was not hosted at the cathedral on 25 December 2019, due to the ongoing restoration work after the fire.[72]

Eight members of the cathedral choir, a number limited by COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, performed inside the building in December 2020 for the first time since the fire more than a year and a half prior. A video of the event aired later, just before midnight on 24 December 2020.[73]

Immediately after the fire, President Macron promised that Notre-Dame would be restored, and called for the work to be completed within five years.[74][75][76][77] An international architectural competition was also announced to redesign the flèche and roof.[78] The hasty flèche competition announcement drew immediate criticism in the international press from heritage academics and professionals who faulted the French government for being too narrowly focused on quickly building a new flèche, and neglecting to frame its response more holistically as an inclusive social process encompassing the whole building and its long-term users.[79][80] A new law was immediately drafted to make Notre-Dame exempt from existing heritage laws and procedures, which prompted an open letter to President Macron signed by over 1,170 heritage experts urging respect for existing regulations.[81] The law, which passed on 11 May 2019, was hotly debated in the French National Assembly, with opponents accusing Macron's administration of using Notre-Dame self-servingly for political grandstanding, and defenders arguing the need for expediency and tax breaks to encourage philanthropic giving.[82]

President Macron suggested he was open to a "contemporary architectural gesture". Even before the competition rules were announced, architects around the world offered suggestions: the proposals included a 100-metre (330 ft) flèche made of carbon fibre, covered with gold leaf; a roof built of stained glass; a greenhouse; a garden with trees, open to the sky; and a column of light pointed upwards. A poll published in the French newspaper Le Figaro on 8 May 2019 showed that 55% of French respondents wanted a flèche identical to the original. French culture minister Franck Riester promised that the restoration "will not be hasty."[83] On 29 July 2019, the French National Assembly enacted a law requiring that the restoration must "preserve the historic, artistic and architectural interest of the monument".[84]

In October 2019, the French government announced that the first stage of reconstruction, the stabilising of the structure against collapse, would take until the end of 2020. In December 2019, Monseigneur Patrick Chauvet, the rector of the cathedral, said there was still a 50% chance that Notre-Dame cannot be saved due to the risk of the remaining scaffolding falling onto the three damaged vaults.[85][86] Reconstruction could not begin before early 2021. President Macron announced that he hoped the reconstructed Cathedral could be finished by Spring 2024, in time for the opening of the 2024 Summer Olympics.[87]

The first task of the restoration was the removal of 250–300 tonnes of melted metal tubes, the remains of the scaffolding, which remained on the top after the fire and could have fallen onto the vaults and caused further structural damage. This stage began in February 2020 and continued through April 2020.[88] A large crane, 84 metres (276 ft) high, was put in place next to the cathedral to help remove the scaffolding.[89] Later, wooden support beams were added to stabilise the flying buttresses and other structures.[90]

On 10 April 2020, the archbishop of Paris, Michel Aupetit, and a handful of participants, all in protective clothing to prevent exposure to lead dust, performed a Good Friday service inside the cathedral.[91] Music was provided by the violinist Renaud Capuçon; the lectors were the actors Philippe Torreton and Judith Chemla.[92] Chemla gave an a cappella rendition of Ave Maria.[93]

A new phase of the restoration commenced on 8 June 2020. Two teams of workers began descending into the roof to remove the tangle of tubes of the old scaffolding melted by the fire. The workers used saws to cut up the forty thousand pieces of scaffolding, weighing altogether two hundred tons, which was carefully lifted out of the roof by an 80-metre-tall (260 ft) crane. The phase was completed in November 2020.[94]

Heading reconstructionIn February 2021, the selection of oak trees to replace the flèche and roof timbers destroyed by the fire began. As many as a thousand mature trees will be chosen from the forests of France, each of a diameter of 50 to 90 centimetres (20 to 35 in) and a height of 8 to 14 metres (26 to 46 ft), and an age of several hundred years. Once cut, the trees must dry for 12 to 18 months. The trees will be replaced by new plantings.[95]

Two years after the fire, a great deal of work had been completed but a news report stated that: "there is still a hole on top of the church. They're also building a replica of the church's spire". More oak trees needed to be shipped to Paris, where they would need to be dried before use; they will be essential in completing the restoration.[96] The oaks used to make the framework are tested and selected by Sylvatest.[97]

On September 18, 2021, the public agency overseeing the Cathedral stated that the safety work was completed, the cathedral was now fully secured, and that reconstruction would begin within a few months.[98]

ResearchIn 2022, a preventive dig carried out between February and April before the construction of a scaffold for reconstructing the cathedral's flèche unearthed several statues and tombs under the cathedral.[99] One of the discoveries included a 14th-century lead sarcophagus that was found 65 feet below where the transept crosses the church's 12th-century nave.[100] On April 14, 2022, France's National Preventive Archaeological Research Institute (INRAP) announced that the sarcophagus was extracted from the cathedral and that scientists have already peeked into the casket using an endoscopic camera, revealing the upper part of a skeleton.[101] Another significant discovery was an opening below the cathedral floor, likely made around 1230 when the Gothic cathedral was first under construction; inside were fragments of a choir screen dating from the 13th century that had been destroyed in the early 18th century.[102] In March 2023, in another significant discovery, archaeologists uncovered thousands of metal staples in various parts of the cathedral, some dating back to the early 1160s. The archaeologists concluded that "Notre Dame is now unquestionably the first known Gothic cathedral where iron was massively used to bind stones as a proper construction material."[103][104][105]

The colour of the restored interior will be "a shock" to some returning visitors, according to General Jean-Louis Georgelin, the French army officer heading the restoration. "The whiteness under the dirt was quite spectacular".[106] The stone was sprayed with a latex solution to lift off accumulated grime and soot. However, the cleaning of the church interior with latex solutions was criticized by Michael Daley of Artwatch UK, referring to the earlier cleaning of Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. He asked, "Is there any good basis for wishing to present an artificially brightened and ahistorical white interior?" [107] Jean-Michel Guilemont of the French Ministry of culture responded, "The interior elevations will regain their original colour, since the chapels and side aisles were very dirty. Of course it is not a white colour. The stone has a blonde colour, and the architects are very attentive to obtaining a patina which respects the centuries".[108]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment