Redwood National and State Parks

The Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP) are a complex of one national park and three California state parks located in the United States along the coast of northern California. The combined RNSP contain Redwood National Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. The parks' 139,000 acres (560 km2) preserve 45 percent of all remaining old-growth coast redwood forests.

Located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties, the four parks protect the endangered coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)—the tallest, among the oldest, and one of the most massive tree species on Earth—which thrives in the humid temperate rainforest. The park region is highly seismically active and prone to tsunamis. The parks preserve 37 miles (60 km) of pristine coastline, indigenous flora, fauna, grassland prairie, cultural resources, waterways, as well as threatened animal speci...Read more

The Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP) are a complex of one national park and three California state parks located in the United States along the coast of northern California. The combined RNSP contain Redwood National Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. The parks' 139,000 acres (560 km2) preserve 45 percent of all remaining old-growth coast redwood forests.

Located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties, the four parks protect the endangered coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)—the tallest, among the oldest, and one of the most massive tree species on Earth—which thrives in the humid temperate rainforest. The park region is highly seismically active and prone to tsunamis. The parks preserve 37 miles (60 km) of pristine coastline, indigenous flora, fauna, grassland prairie, cultural resources, waterways, as well as threatened animal species, such as the Chinook salmon, northern spotted owl, and Steller's sea lion.

Redwood forest originally covered more than two million acres (8,100 km2) of the California coast, and the region of today's parks largely remained wild until after 1850. The gold rush and attendant timber business unleashed a torrent of European-American activity, pushing Native Americans aside and supplying lumber to the West Coast. Decades of unrestricted clear-cut logging ensued, followed by ardent conservation efforts. In the 1920s, the Save the Redwoods League helped create Prairie Creek, Del Norte Coast, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks among others. After lobbying from the league and the Sierra Club, Congress created Redwood National Park in 1968 and expanded it in 1978. In 1994, the National Park Service (NPS) and the California Department of Parks and Recreation combined Redwood National Park with the three abutting Redwoods State Parks into a single administrative unit. Modern RNSP management seeks to both protect and restore the coast redwood forests to their condition before 1850, including by controlled burning.

In recognition of the rare ecosystem and cultural history found in the parks, the United Nations designated them a World Heritage Site in 1980. Local tribes declared an Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area in 2023, protecting the parks region, the coastline, and coastal waters. Park admission is free except for special permits, and visitors may camp, hike, bike, and ride horseback along about 200 miles of park system trails.

A Tolowa woman working park maintenance in 1982

A Tolowa woman working park maintenance in 1982Modern day Native American nations such as the Yurok, Tolowa, Karuk, Chilula, and Wiyot have historical ties to the region,[1] which has had various indigenous occupants for millennia.[2] Describing "a diversity in an area that size that has probably has never been equaled anywhere else in the world", historian David Stannard accounts for more than thirty native nations that lived in northwestern California.[3] Scholar Gail L. Jenner estimates that "at least fifteen" tribal groups inhabited the coastline.[4]

The Yurok, Chilula, and Tolowa were the most connected to the current parks' areas.[5] Based on an 1852 census, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated that the Yurok population in that year was around 2,500.[1] Historian Ed Bearss described the Yurok as the most populous in the area, estimating that there were around 55 villages.[1] Until the 1860s, the Chilula lived in the middle region of the Redwood Creek valley in close company with the redwood trees.[6] They primarily settled along Redwood Creek between the coast and Minor Creek, California, and in summer they would range into and camp in the Bald Hills.[7] The Tolowa were located near the Smith River, and on lands that are now part of Jedediah Smith State Park, an area which 21st century excavation found has been inhabited for at least 8,500 years.[8]

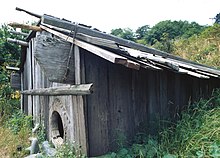

Native Americans residing within the park areas relied on redwood trees as a construction material, and some featured the trees in their mythology, including the Chilula, who viewed the trees as gifts from a creator.[9] The tribes harvested coast redwoods and processed them into planks, using them as building material for boats, houses, and small villages.[10] To construct buildings, the planks would be erected side by side in a narrow trench, with the upper portions lashed with willow or hazel and held by notches cut into the supporting roof beams. Redwood boards were used to form a two- or three-pitch roof.[11]

Reconstructed Yurok plankhouse made of redwood boardsArrival of European Americans

Reconstructed Yurok plankhouse made of redwood boardsArrival of European Americans

Historians believe that the first Europeans to visit land near what is now the parks were members of the Cabrillo expedition led by Bartolomé Ferrer.[12] In 1543, Ferrer's ship made landfall at Cape Mendocino and may have reached waters off Oregon as far north as the 43rd parallel.[12] Hubert Howe Bancroft disagreed, believing that Ferrer's ship did not travel so far north.[12] Explorers including Francis Drake sailed past[13] the foggy, rocky coast, but generally did not set anchor until 1775, when Bruno de Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra of Spain spent about ten days at the Yurok village of Tsurai south of the parks.[14] George Vancouver and Francisco de Eliza followed in 1793.[14] American fur trading ships under contract to Russians stopped at Tsurai during the early 19th century.[15]

Prior to Jedediah Smith in 1828, no other explorer of European descent is known to have explored the interior of the Northern California coastal region. Smith and nineteen companions left San Jose, California, and explored what are now called the Trinity, Smith, and Klamath rivers, passing through coast redwood forests and trading with Native American groups. They reached the coast near Requa, parts of which are within the parks' boundaries.[16]

The California Gold Rush of 1848 brought hundreds of thousands of Europeans and Americans to California,[17] and the discovery of gold along the Trinity River in 1850 brought many of them to the region of the parks. This quickly led to conflicts wherein native peoples were displaced, raped, enslaved, and massacred.[18] By 1895, only one third of the Yurok in one group of villages remained; by 1919, virtually all members of the Chilula tribe had either died or been assimilated into other tribes.[19] The Tolowa—whose numbers Bearss estimates at "well under 1,000" by the 1850s—had a population of about 120 in 1910,[20] having been nearly extinguished in massacres by settlers between 1853 and 1855.[21]

Redwood logging followed gold mining, and most mining companies became lumber interests.[22] Redwood has a straight grain making planks easy to cut, it can defy the weather, it does not warp, and it became a valuable commodity.[23] Jenner says a good team of two men could saw through a redwood tree at about a foot per hour with a crosscut saw, their preferred tool until after World War II.[24] Because wheeled vehicles could not travel the landscape, teams of six or twelve oxen transported logs to logging roads.[25] Rivers or railroads took them to the region's lumber mills.[26] After the 1881 invention of the steam donkey and later its successor the bull donkey, the need to fell intervening trees so the donkeys could work spawned the practice called clearcutting.[27] Caterpillar tractors began to compete with manual labor in the late 1920s.[28]

State park preservation The coast redwood is the tallest tree species on Earth.

The coast redwood is the tallest tree species on Earth.After extensive logging, conservationists and concerned citizens began to seek ways to preserve remaining trees, which they saw being logged at an alarming rate.[29] Stumbling blocks slowed conservation: objections and some innovations came from the logging industry,[a] construction of the Redwood Highway brought roadside attractions and more visitors to the trees,[32] Congress failed to act,[b] and voracious demand for lumber came with the post-World War II construction boom.[c]

Organizations formed to preserve the surviving trees:[34] concerned about the sequoia of Yosemite, John Muir cofounded the Sierra Club in 1892.[35] The Sempervirens Club was cofounded in 1900 by artist Andrew P. Hill who lobbied the media, and saw the oldest state park created along with the California state park system.[36] In 1916, politician William Kent purchased land outright and helped to write the bill founding the National Park Service (NPS). In 1918, John Merriam and other members of the Boone and Crockett Club[37] founded the Save the Redwoods League.[38] The league bought land and donated funds for land purchases. Historian Susan Schrepfer writes that, in a sixty-year-long marathon, the Save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club were racing the logging companies for the old trees.[39]

At first, in 1919, with Congress showing interest but no appropriations, NPS director Stephen Mather formed the NPS system with private wealth[40]—he and his wealthy friends purchased parkland with their own money.[41] Balancing opponents and supporters, the Save the Redwoods League saw their compromise bill pass in 1923, allowing condemnation for park acquisition with state oversight.[42] In 1925, the league backed a bill that would authorize a statewide survey by a landscape architect and permit land acquisition and condemnation for parks. In 1926, the league retained Frederick Law Olmsted to make that survey.[43] The league added to their bill a proposed state constitutional amendment authorizing up to $6 million ($99.2 million in 2022) in bonds to equally match private donations for state land purchases.[44] After sustaining a governor's veto in 1925,[43] the league broadened its efforts to include the whole state, mounted a publicity campaign, and gained the support of the Los Angeles Times.[45] A new governor signed the parks bill into law in 1927, and the bond issue was approved in the 1928 election.[45]

A map of Redwood National and State Parks (2020)

A map of Redwood National and State Parks (2020)In 1927, Olmsted's survey was complete, and concluded that only three percent of the state's redwoods could be preserved. He recommended four redwood areas for parks which became Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks. A fourth became Humboldt Redwoods State Park, by far the largest of the individual Redwoods State Parks, but not in the Redwood National and State Parks system.[46] Now armed with matching funds after 1928, the league bought more land and added to these parks as conditions allowed.[47]

National parkThe NPS proposed a redwoods national park in 1938. The Save the Redwoods League opposed it, highlighting a division between preservationists who preferred unembellished nature and a segment of the park service who wished to provide recreation and playgrounds for the public.[48] Both the league and the Sierra Club wanted a redwoods national park by the 1960s, but the club and the league supported different locations.[49] The club and the league were antagonists during the 1960s,[50] often on opposite sides of national park arguments, until 1971 when the league backed a club position,[51] and the late 1970s when the league became a club member.[52]

The Sierra Club wanted the largest possible park and usually sought help from the federal government.[53] More cautious, the Save the Redwoods League tended to accommodate industry and support the state of California.[54] When the agency had no funds in 1963, the National Geographic Society funded an NPS survey of the redwoods.[55] In 1964, NPS released its ideas for three different sized redwood national parks.[56] In 1964, Congress passed the Land and Water Conservation Fund to allow federal funds to purchase parkland.[57]

Describing a reason for the club's success, Willard Pratt of the Arcata lumber company writes, "The Sierra Club demonstrated a basic political fact of life: Opposition to particular preservation proposals usually is local while support is national. If decision making can be placed at the national level, preservation usually can win".[58]

Initially opposing the park in the 1960s, the Arcata, Georgia-Pacific, and Miller lumber businesses operated right up to the boundaries being discussed.[59] In 1965, five logging companies formally objected to any redwood national park.[58] Schrepfer writes that the final bill divided the impact between the lumber companies, between California counties, and tried to appeal to both the league and the club. Schrepfer says that in large part, the bill was framed on the loggers' terms.[60] After intense lobbying of Congress, the bill creating Redwood National Park was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in October 1968.[61]

The Save the Redwoods League donated parcels in 1974 and 1976.[62] The club found the Olmsted plan of delicately choosing sites was the wrong approach to defend against tractor clearcutting.[63] In 1977, the club said that only ridge-to-ridge land acquisition around a water channel could preserve a watershed and thus the trees.[64] Amidst both local support of environmentalists and opposition from local loggers and logging companies, 48,000 acres (190 km2) were added to Redwood National Park in an expansion signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1978.[65] The purchase included lands that had already been logged, and the NPS was charged with restoring the land and reducing soil erosion.[66] At hundreds of millions of dollars, it was the most expensive land purchase ever approved by Congress.[65] By 1979, the league had preserved 150,000 acres (610 km2) or nearly twice the area that the federal government was able to save with park legislation.[63]

Further recognitionThe United Nations designated the Redwood National and State Parks a World Heritage Site in 1980. The evaluation committee noted cooperative management and ongoing research in the parks by Humboldt State University and other partners.[67] The parks are within the California Coast Ranges and their resources are considered irreplaceable.[68] In 1983, the parks were designated an International Biosphere Reserve.[69] In 2017, the US withdrew them along with more than a dozen other reserves from the World Network of Biosphere Reserves.[70]

In 2023, following the lead of First Nations in Canada and Aboriginal people in Australia, three federally recognized indigenous tribes—the Resighini Rancheria of the Yurok People, Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation, and Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria—announced that as sovereign governments they have protected the Yurok-Tolowa-Dee-ni' Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area.[71] The effort protected 700 square miles (1,800 km2) of territorial ocean waters and coastline reaching from Oregon to just south of Trinidad,[71] and contributed to the California 30x30 plan to conserve 30% of the state's land and coastal water by 2030.[72] The tribes invited cooperation with US agencies and other indigenous nations.[73]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment