Natural History Museum, London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road.

The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology and zoology. The museum is a centre of research specialising in taxonomy, identification and conservation. Given the age of the institution, many of the collections have great historical as well as scientific value, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin. The museum is particularly famous for its exhibition of dinosaur skeletons and ornate architecture—sometimes dubbed a cathedral of nature—both exemplified by the large ...Read more

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road.

The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology and zoology. The museum is a centre of research specialising in taxonomy, identification and conservation. Given the age of the institution, many of the collections have great historical as well as scientific value, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin. The museum is particularly famous for its exhibition of dinosaur skeletons and ornate architecture—sometimes dubbed a cathedral of nature—both exemplified by the large Diplodocus cast that dominated the vaulted central hall before it was replaced in 2017 with the skeleton of a blue whale hanging from the ceiling. The Natural History Museum Library contains an extensive collection of books, journals, manuscripts, and artwork linked to the work and research of the scientific departments; access to the library is by appointment only. The museum is recognised as the pre-eminent centre of natural history and research of related fields in the world.

Although commonly referred to as the Natural History Museum, it was officially known as British Museum (Natural History) until 1992, despite legal separation from the British Museum itself in 1963. Originating from collections within the British Museum, the landmark Alfred Waterhouse building was built and opened by 1881 and later incorporated the Geological Museum. The Darwin Centre is a more recent addition, partly designed as a modern facility for storing the valuable collections.

Like other publicly funded national museums in the United Kingdom, the Natural History Museum does not charge an admission fee. The museum is an exempt charity and a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. The Princess of Wales is a patron of the museum. There are approximately 850 staff at the museum. The two largest strategic groups are the Public Engagement Group and Science Group.

An 1881 plan showing the original arrangement of the museum.

An 1881 plan showing the original arrangement of the museum.(Link to current floor plans).

The foundation of the collection was that of the Ulster doctor Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), who allowed his significant collections to be purchased by the British Government at a price well below their market value at the time. This purchase was funded by a lottery. Sloane's collection, which included dried plants, and animal and human skeletons, was initially housed in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, in 1756, which was the home of the British Museum.

Most of the Sloane collection had disappeared by the early decades of the nineteenth century. Dr George Shaw (Keeper of Natural History 1806–1813) sold many specimens to the Royal College of Surgeons and had periodic cremations of material in the grounds of the museum. His successors also applied to the trustees for permission to destroy decayed specimens.[1] In 1833, the Annual Report states that, of the 5,500 insects listed in the Sloane catalogue, none remained. The inability of the natural history departments to conserve its specimens became notorious: the Treasury refused to entrust it with specimens collected at the government's expense. Appointments of staff were bedevilled by gentlemanly favouritism; in 1862 a nephew of the mistress of a Trustee was appointed Entomological Assistant despite not knowing the difference between a butterfly and a moth.[2][3][verification needed]

J. E. Gray (Keeper of Zoology 1840–1874) complained of the incidence of mental illness amongst staff: George Shaw threatened to put his foot on any shell not in the 12th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae; another had removed all the labels and registration numbers from entomological cases arranged by a rival. The huge collection of the conchologist Hugh Cuming was acquired by the museum, and Gray's own wife had carried the open trays across the courtyard in a gale: all the labels blew away. That collection is said never to have recovered.[4][page needed]

The Principal Librarian at the time was Antonio Panizzi; his contempt for the natural history departments and for science in general was total. The general public was not encouraged to visit the museum's natural history exhibits. In 1835 to a Select Committee of Parliament, Sir Henry Ellis said this policy was fully approved by the Principal Librarian and his senior colleagues.

Many of these faults were corrected by the palaeontologist Richard Owen, appointed Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum in 1856. His changes led Bill Bryson to write that "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".[5][page needed]

Planning and architecture of new building The Natural History Museum, shown in wide-angle view here, has an ornate terracotta facade by Gibbs and Canning typical of high Victorian architecture. The terracotta mouldings represent the past and present diversity of nature.

The Natural History Museum, shown in wide-angle view here, has an ornate terracotta facade by Gibbs and Canning typical of high Victorian architecture. The terracotta mouldings represent the past and present diversity of nature.Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards. The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent.[6] The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre.

The Comic News reporting on the movement to South Kensington in 1863

The Comic News reporting on the movement to South Kensington in 1863Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of Victorian London, manufactured by the Tamworth-based company of Gibbs and Canning. The tiles and bricks feature many relief sculptures of flora and fauna, with living and extinct species featured within the west and east wings respectively. This explicit separation was at the request of Owen, and has been seen as a statement of his contemporary rebuttal of Darwin's attempt to link present species with past through the theory of natural selection.[7] Though Waterhouse slipped in a few anomalies, such as bats amongst the extinct animals and a fossil ammonite with the living species. The sculptures were produced from clay models by a French sculptor based in London, M Dujardin, working to drawings prepared by the architect.[8]

The central axis of the museum is aligned with the tower of Imperial College London (formerly the Imperial Institute) and the Royal Albert Hall and Albert Memorial further north. These all form part of the complex known colloquially as Albertopolis.

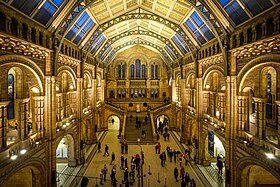

Separation from the British Museum The central hall of the museum

The central hall of the museumEven after the opening, the Natural History Museum legally remained a department of the British Museum with the formal name British Museum (Natural History), usually abbreviated in the scientific literature as B.M.(N.H.). A petition to the Chancellor of the Exchequer was made in 1866, signed by the heads of the Royal, Linnean and Zoological societies as well as naturalists including Darwin, Wallace and Huxley, asking that the museum gain independence from the board of the British Museum, and heated discussions on the matter continued for nearly one hundred years. Finally, with the passing of the British Museum Act 1963, the British Museum (Natural History) became an independent museum with its own board of trustees, although – despite a proposed amendment to the act in the House of Lords – the former name was retained. In 1989 the museum publicly re-branded itself as the Natural History Museum and stopped using the title British Museum (Natural History) on its advertising and its books for general readers. Only with the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 did the museum's formal title finally change to the Natural History Museum.

Geological MuseumIn 1985, the museum merged with the adjacent Geological Museum of the British Geological Survey,[9][10] which had long competed for the limited space available in the area. The Geological Museum became world-famous for exhibitions including an active volcano model and an earthquake machine (designed by James Gardner), and housed the world's first computer-enhanced exhibition (Treasures of the Earth). The museum's galleries were completely rebuilt and relaunched in 1996 as The Earth Galleries, with the other exhibitions in the Waterhouse building retitled The Life Galleries. The Natural History Museum's own mineralogy displays remain largely unchanged as an example of the 19th-century display techniques of the Waterhouse building.

The central atrium design by Neal Potter overcame visitors' reluctance to visit the upper galleries by "pulling" them through a model of the Earth made up of random plates on an escalator. The new design covered the walls in recycled slate and sandblasted the major stars and planets onto the wall. The museum's 'star' geological exhibits are displayed within the walls. Six iconic figures were the backdrop to discussing how previous generations have viewed Earth. These were later removed to make place for a Stegosaurus skeleton that was put on display in late 2015.

The Darwin Centre Statue of Charles Darwin by Sir Joseph Boehm, 1885, in the main hall

Statue of Charles Darwin by Sir Joseph Boehm, 1885, in the main hallThe Darwin Centre (named after Charles Darwin) was designed as a new home for the museum's collection of tens of millions of preserved specimens, as well as new work spaces for the museum's scientific staff and new educational visitor experiences. Built in two distinct phases, with two new buildings adjacent to the main Waterhouse building, it is the most significant new development project in the museum's history.

Phase one of the Darwin Centre opened to the public in 2002, and it houses the zoological department's 'spirit collections'—organisms preserved in alcohol. Phase Two was unveiled in September 2008 and opened to the general public in September 2009. It was designed by the Danish architecture practice C. F. Møller Architects in the shape of a giant, eight-story cocoon and houses the entomology and botanical collections—the 'dry collections'.[11] It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily.[12]

Arguably the most famous creature in the centre is the 8.62-metre-long giant squid, affectionately named Archie.[13]

The Attenborough StudioAs part of the museum's remit to communicate science education and conservation work, a new multimedia studio forms an important part of Darwin Centre Phase 2. In collaboration with the BBC's Natural History Unit (holder of the largest archive of natural history footage) the Attenborough Studio—named after the broadcaster Sir David Attenborough—provides a multimedia environment for educational events. The studio holds regular lectures and demonstrations, including free Nature Live talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Add new comment