Colombia

Context of Colombia

Colombia ( (listen), ; Spanish: [koˈlombja] (listen)), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuela to the east and northeast, Brazil to the southeast, Ecuador and Peru to the south and southwest, the Pacific Ocean to the west, and Panama to the northwest. Colombia is divided into 32 departments. The Capital District of Bogotá is also the country's largest city. It covers an area of 1,141,748 square kilometers (440,8...Read more

Colombia ( (listen), ; Spanish: [koˈlombja] (listen)), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuela to the east and northeast, Brazil to the southeast, Ecuador and Peru to the south and southwest, the Pacific Ocean to the west, and Panama to the northwest. Colombia is divided into 32 departments. The Capital District of Bogotá is also the country's largest city. It covers an area of 1,141,748 square kilometers (440,831 sq mi), and has a population of around 52 million. Colombia's cultural heritage—including language, religion, cuisine, and art—reflects its history as a Spanish colony, fusing cultural elements brought by immigration from Europe and the Middle East, with those brought by enslaved Africans, as well as with those of the various Indigenous civilizations that predate colonization. Spanish is the official state language, although English and 64 other languages are recognized regional languages.

Colombia has been home to many indigenous peoples and cultures since at least 12,000 BCE. The Spanish first landed in La Guajira in 1499, and by the mid-16th century they had explored and colonized much of present-day Colombia, and established the New Kingdom of Granada, with Santa Fé de Bogotá as its capital. Independence from the Spanish Empire was achieved in 1819, with what is now Colombia emerging as the United Provinces of New Granada. The new polity experimented with federalism as the Granadine Confederation (1858) and then the United States of Colombia (1863), before becoming a republic—the current Republic of Colombia—in 1886. With the backing of the United States and France, Panama seceded from Colombia in 1903, resulting in Colombia's present borders. Beginning in the 1960s, the country has suffered from an asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict and political violence, both of which escalated in the 1990s. Since 2005, there has been significant improvement in security, stability and rule of law, as well as unprecedented economic growth and development. Colombia is recognized for its health system, being the best healthcare in the Americas according to The World Health Organization and 22nd on the planet, In 2022, 26 Colombian hospitals were among the 61 best in Latin America (42% total). Also in 2023, two Colombian hospitals were among the Top 75 of the world.

Colombia is one of the world's seventeen megadiverse countries; it has the second-highest level of biodiversity in the world. Its territory encompasses Amazon rainforest, highlands, grasslands and deserts. It is the only country in South America with coastlines and islands along both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Colombia is a member of major global and regional organizations including the UN, the WTO, the OECD, the OAS, the Pacific Alliance and the Andean Community; it is also a NATO Global Partner. Its diversified economy is the third-largest in South America, with macroeconomic stability and favorable long-term growth prospects.

More about Colombia

- Currency Colombian peso

- Native name Colombia

- Calling code +57

- Internet domain .co

- Mains voltage 110V/60Hz

- Democracy index 7.04

- Population 49065615

- Area 1141748

- Driving side right

- Pre-Columbian era

Location map of the pre-Columbian cultures of Colombia

Location map of the pre-Columbian cultures of ColombiaOwing to its location, the present territory of Colombia was a corridor of early human civilization from Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to the Andes and Amazon basin. The oldest archaeological finds are from the Pubenza and El Totumo sites in the Magdalena Valley 100 kilometers (62 mi) southwest of Bogotá.[1] These sites date from the Paleoindian period (18,000–8000 BCE). At Puerto Hormiga and other sites, traces from the Archaic Period (~8000–2000 BCE) have been found....Read more

Pre-Columbian eraRead less Location map of the pre-Columbian cultures of Colombia

Location map of the pre-Columbian cultures of ColombiaOwing to its location, the present territory of Colombia was a corridor of early human civilization from Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to the Andes and Amazon basin. The oldest archaeological finds are from the Pubenza and El Totumo sites in the Magdalena Valley 100 kilometers (62 mi) southwest of Bogotá.[1] These sites date from the Paleoindian period (18,000–8000 BCE). At Puerto Hormiga and other sites, traces from the Archaic Period (~8000–2000 BCE) have been found. Vestiges indicate that there was also early occupation in the regions of El Abra and Tequendama in Cundinamarca. The oldest pottery discovered in the Americas, found at San Jacinto, dates to 5000–4000 BCE.[2]

Indigenous people inhabited the territory that is now Colombia by 12,500 BCE. Nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes at the El Abra, Tibitó and Tequendama sites near present-day Bogotá traded with one another and with other cultures from the Magdalena River Valley.[3] A site including eight miles (13 km) of pictographs that is under study at Serranía de la Lindosa was revealed in November 2020.[4] Their age is suggested as being 12,500 years old (c. 10,480 B.C.) by the anthropologists working on the site because of extinct fauna depicted. That would have been during the earliest known human occupation of the area now known as Colombia.[citation needed]

Between 5000 and 1000 BCE, hunter-gatherer tribes transitioned to agrarian societies; fixed settlements were established, and pottery appeared. Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, groups of Amerindians including the Muisca, Zenú, Quimbaya, and Tairona developed the political system of cacicazgos with a pyramidal structure of power headed by caciques. The Muisca inhabited mainly the area of what is now the Departments of Boyacá and Cundinamarca high plateau (Altiplano Cundiboyacense) where they formed the Muisca Confederation. They farmed maize, potato, quinoa, and cotton, and traded gold, emeralds, blankets, ceramic handicrafts, coca and especially rock salt with neighboring nations. The Tairona inhabited northern Colombia in the isolated mountain range of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.[5] The Quimbaya inhabited regions of the Cauca River Valley between the Western and Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes.[6] Most of the Amerindians practiced agriculture and the social structure of each indigenous community was different. Some groups of indigenous people such as the Caribs lived in a state of permanent war, but others had less bellicose attitudes.[7]

Colonial period Vasco Núñez de Balboa, founder of Santa María la Antigua del Darién the first stable European settlement on the continent

Vasco Núñez de Balboa, founder of Santa María la Antigua del Darién the first stable European settlement on the continentAlonso de Ojeda (who had sailed with Columbus) reached the Guajira Peninsula in 1499.[8][9] Spanish explorers, led by Rodrigo de Bastidas, made the first exploration of the Caribbean coast in 1500.[10] Christopher Columbus navigated near the Caribbean in 1502.[11] In 1508, Vasco Núñez de Balboa accompanied an expedition to the territory through the region of Gulf of Urabá and they founded the town of Santa María la Antigua del Darién in 1510, the first stable settlement on the continent. [Note 1][12] Santa Marta was founded in 1525,[13] and Cartagena in 1533.[14] Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada led an expedition to the interior in April 1536, and christened the districts through which he passed "New Kingdom of Granada". In August 1538, he founded provisionally its capital near the Muisca cacicazgo of Muyquytá, and named it "Santa Fe". The name soon acquired a suffix and was called Santa Fe de Bogotá.[15][16] Two other notable journeys by early conquistadors to the interior took place in the same period. Sebastián de Belalcázar, conqueror of Quito, traveled north and founded Cali, in 1536, and Popayán, in 1537;[17] from 1536 to 1539, German conquistador Nikolaus Federmann crossed the Llanos Orientales and went over the Cordillera Oriental in a search for El Dorado, the "city of gold".[18][19] The legend and the gold would play a pivotal role in luring the Spanish and other Europeans to New Granada during the 16th and 17th centuries.[20]

The conquistadors made frequent alliances with the enemies of different indigenous communities. Indigenous allies were crucial to conquest, as well as to creating and maintaining empire.[21] Indigenous peoples in New Granada experienced a decline in population due to conquest as well as Eurasian diseases, such as smallpox, to which they had no immunity.[22][23] Regarding the land as deserted, the Spanish Crown sold properties to all persons interested in colonized territories, creating large farms and possession of mines.[24][25][26] In the 16th century, the nautical science in Spain reached a great development thanks to numerous scientific figures of the Casa de Contratación and nautical science was an essential pillar of the Iberian expansion.[27] In 1542, the region of New Granada, along with all other Spanish possessions in South America, became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, with its capital in Lima.[28] In 1547, New Granada became a separate captaincy-general within the viceroyalty, with its capital at Santa Fe de Bogota.[29] In 1549, the Royal Audiencia was created by a royal decree, and New Granada was ruled by the Royal Audience of Santa Fe de Bogotá, which at that time comprised the provinces of Santa Marta, Rio de San Juan, Popayán, Guayana and Cartagena.[30] But important decisions were taken from the colony to Spain by the Council of the Indies.[31][32]

An illustration of the Battle of Cartagena de Indias, a major Spanish victory in the War of Jenkins' Ear[33]

An illustration of the Battle of Cartagena de Indias, a major Spanish victory in the War of Jenkins' Ear[33]In the 16th century, European slave traders had begun to bring enslaved Africans to the Americas. Spain was the only European power that did not establish factories in Africa to purchase slaves; the Spanish Empire instead relied on the asiento system, awarding merchants from other European nations the license to trade enslaved peoples to their overseas territories.[34][35] This system brought Africans to Colombia, although many spoke out against the institution.[Note 2][Note 3] The indigenous peoples could not be enslaved because they were legally subjects of the Spanish Crown.[40] To protect the indigenous peoples, several forms of land ownership and regulation were established by the Spanish colonial authorities: resguardos, encomiendas and haciendas.[24][25][26]

However, secret anti-Spanish discontentment was already brewing for Colombians since Spain prohibited direct trade between the Viceroyalty of Peru, which included Colombia, and the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included the Philippines, the source of Asian products like silk and porcelain which was in demand in the Americas. Illegal trade between Peruvians, Filipinos, and Mexicans continued in secret, as smuggled Asian goods ended up in Córdoba, Colombia, the distribution center for illegal Asian imports, due to the collusion between these peoples against the authorities in Spain. They settled and traded with each other while disobeying the forced Spanish monopoly.[41]

Mapa of the Viceroyalty of New Granada

Mapa of the Viceroyalty of New GranadaThe Viceroyalty of New Granada was established in 1717, then temporarily removed, and then re-established in 1739. Its capital was Santa Fé de Bogotá. This Viceroyalty included some other provinces of northwestern South America that had previously been under the jurisdiction of the Viceroyalties of New Spain or Peru and correspond mainly to today's Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. So, Bogotá became one of the principal administrative centers of the Spanish possessions in the New World, along with Lima and Mexico City, though it remained somewhat backward compared to those two cities in several economic and logistical ways.[42][43]

Great Britain declared war on Spain in 1739, and the city of Cartagena quickly became a top target for the British. A massive British expeditionary force was dispatched to capture the city, but after initial inroads devastating outbreaks of disease crippled their numbers and the British were forced to withdraw. The battle became one of Spain's most decisive victories in the conflict, and secured Spanish dominance in the Caribbean until the Seven Years' War.[33][44] The 18th-century priest, botanist and mathematician José Celestino Mutis was delegated by Viceroy Antonio Caballero y Góngora to conduct an inventory of the nature of New Granada. Started in 1783, this became known as the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada. It classified plants and wildlife, and founded the first astronomical observatory in the city of Santa Fe de Bogotá.[45] In July 1801 the Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt reached Santa Fe de Bogotá where he met with Mutis. In addition, historical figures in the process of independence in New Granada emerged from the expedition as the astronomer Francisco José de Caldas, the scientist Francisco Antonio Zea, the zoologist Jorge Tadeo Lozano and the painter Salvador Rizo.[46][47]

Independence Formation of the present Colombia since the Viceroyalty of New Granada's independence from the Spanish Empire

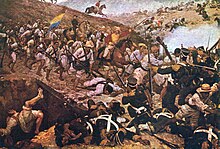

Formation of the present Colombia since the Viceroyalty of New Granada's independence from the Spanish Empire The Battle of Boyacá was the decisive battle that ensured success of the liberation campaign of New Granada.

The Battle of Boyacá was the decisive battle that ensured success of the liberation campaign of New Granada.Since the beginning of the periods of conquest and colonization, there were several rebel movements against Spanish rule, but most were either crushed or remained too weak to change the overall situation. The last one that sought outright independence from Spain sprang up around 1810 and culminated in the Colombian Declaration of Independence, issued on 20 July 1810, the day that is now celebrated as the nation's Independence Day.[48] This movement followed the independence of St. Domingue (present-day Haiti) in 1804, which provided some support to an eventual leader of this rebellion: Simón Bolívar. Francisco de Paula Santander also would play a decisive role.[49][50][51]

A movement was initiated by Antonio Nariño, who opposed Spanish centralism and led the opposition against the Viceroyalty.[52] Cartagena became independent in November 1811.[53] In 1811, the United Provinces of New Granada were proclaimed, headed by Camilo Torres Tenorio.[54][55] The emergence of two distinct ideological currents among the patriots (federalism and centralism) gave rise to a period of instability.[56] Shortly after the Napoleonic Wars ended, Ferdinand VII, recently restored to the throne in Spain, unexpectedly decided to send military forces to retake most of northern South America. The viceroyalty was restored under the command of Juan Sámano, whose regime punished those who participated in the patriotic movements, ignoring the political nuances of the juntas.[57] The retribution stoked renewed rebellion, which, combined with a weakened Spain, made possible a successful rebellion led by the Venezuelan-born Simón Bolívar, who finally proclaimed independence in 1819.[58][59] The pro-Spanish resistance was defeated in 1822 in the present territory of Colombia and in 1823 in Venezuela.[60][61][62]

The territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada became the Republic of Colombia, organized as a union of the current territories of Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Venezuela, parts of Guyana and Brazil and north of Marañón River.[63] The Congress of Cúcuta in 1821 adopted a constitution for the new Republic.[64][65] Simón Bolívar became the first President of Colombia, and Francisco de Paula Santander was made Vice President.[66] However, the new republic was unstable and the Gran Colombia ultimately collapsed.

Modern Colombia comes from one of the countries that emerged after the dissolution of Gran Colombia, the other two being Ecuador and Venezuela.[67][68][69] Colombia was the first constitutional government in South America,[70] and the Liberal and Conservative parties, founded in 1848 and 1849, respectively, are two of the oldest surviving political parties in the Americas.[71] Slavery was abolished in the country in 1851.[72][73]

Internal political and territorial divisions led to the dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1830.[67][68] The so-called "Department of Cundinamarca" adopted the name "New Granada", which it kept until 1858 when it became the "Confederación Granadina" (Granadine Confederation). After a two-year civil war in 1863, the "United States of Colombia" was created, lasting until 1886, when the country finally became known as the Republic of Colombia.[70][74] Internal divisions remained between the bipartisan political forces, occasionally igniting very bloody civil wars, the most significant being the Thousand Days' War (1899–1902).[75]

20th centuryThe United States of America's intentions to influence the area (especially the Panama Canal construction and control)[76] led to the separation of the Department of Panama in 1903 and the establishment of it as a nation.[77] The United States paid Colombia $25,000,000 in 1921, seven years after completion of the canal, for redress of President Roosevelt's role in the creation of Panama, and Colombia recognized Panama under the terms of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty.[78] Colombia and Peru went to war because of territory disputes far in the Amazon basin. The war ended with a peace deal brokered by the League of Nations. The League finally awarded the disputed area to Colombia in June 1934.[79]

The Bogotazo in 1948

The Bogotazo in 1948Soon after, Colombia achieved some degree of political stability, which was interrupted by a bloody conflict that took place between the late 1940s and the early 1950s, a period known as La Violencia ("The Violence"). Its cause was mainly mounting tensions between the two leading political parties, which subsequently ignited after the assassination of the Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on 9 April 1948.[80][81] The ensuing riots in Bogotá, known as El Bogotazo, spread throughout the country and claimed the lives of at least 180,000 Colombians.[82]

Colombia entered the Korean War when Laureano Gómez was elected president. It was the only Latin American country to join the war in a direct military role as an ally of the United States. Particularly important was the resistance of the Colombian troops at Old Baldy.[83]

The violence between the two political parties decreased first when Gustavo Rojas deposed the President of Colombia in a coup d'état and negotiated with the guerrillas, and then under the military junta of General Gabriel París.[84][85]

The Axis of Peace and Memory, a memorial to the victims of the Colombian conflict (1964–present)

The Axis of Peace and Memory, a memorial to the victims of the Colombian conflict (1964–present)After Rojas' deposition, the Colombian Conservative Party and Colombian Liberal Party agreed to create the National Front, a coalition that would jointly govern the country. Under the deal, the presidency would alternate between conservatives and liberals every 4 years for 16 years; the two parties would have parity in all other elective offices.[86] The National Front ended "La Violencia", and National Front administrations attempted to institute far-reaching social and economic reforms in cooperation with the Alliance for Progress.[87][88] Despite the progress in certain sectors, many social and political problems continued, and guerrilla groups were formally created such as the FARC, the ELN and the M-19 to fight the government and political apparatus.[89]

Since the 1960s, the country has suffered from an asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict between government forces, leftist guerrilla groups and right wing paramilitaries.[90] The conflict escalated in the 1990s,[91] mainly in remote rural areas.[92] Since the beginning of the armed conflict, human rights defenders have fought for the respect for human rights, despite staggering opposition.[Note 4][Note 5] Several guerrillas' organizations decided to demobilize after peace negotiations in 1989–1994.[96]

The United States has been heavily involved in the conflict since its beginnings, when in the early 1960s the U.S. government encouraged the Colombian military to attack leftist militias in rural Colombia. This was part of the U.S. fight against communism. Mercenaries and multinational corporations such as Chiquita Brands International are some of the international actors that have contributed to the violence of the conflict.[90][96][97]

Beginning in the mid-1970s Colombian drug cartels became major producers, processors and exporters of illegal drugs, primarily marijuana and cocaine.[98]

On 4 July 1991, a new Constitution was promulgated. The changes generated by the new constitution are viewed as positive by Colombian society.[99][100]

21st century Former President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace accord

Former President Juan Manuel Santos signed a peace accordThe administration of President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010) adopted the democratic security policy which included an integrated counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency campaign.[101] The government economic plan also promoted confidence in investors.[102] As part of a controversial peace process, the AUC (right-wing paramilitaries) had ceased to function formally as an organization .[103] In February 2008, millions of Colombians demonstrated against FARC and other outlawed groups.[104]

After peace negotiations in Cuba, the Colombian government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the guerrillas of the FARC-EP announced a final agreement to end the conflict.[105] However, a referendum to ratify the deal was unsuccessful.[106][107] Afterward, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a revised peace deal in November 2016,[108] which the Colombian congress approved.[109] In 2016, President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[110] The Government began a process of attention and comprehensive reparation for victims of conflict.[111][112] Colombia shows modest progress in the struggle to defend human rights, as expressed by HRW.[113] A Special Jurisdiction of Peace has been created to investigate, clarify, prosecute and punish serious human rights violations and grave breaches of international humanitarian law which occurred during the armed conflict and to satisfy victims' right to justice.[114] During his visit to Colombia, Pope Francis paid tribute to the victims of the conflict.[115]

Gustavo Petro, the country's first left-wing president

Gustavo Petro, the country's first left-wing presidentIn June 2018, Ivan Duque, the candidate of the right-wing Democratic Center party, won the presidential election.[116] On 7 August 2018, he was sworn in as the new President of Colombia to succeed Juan Manuel Santos.[117] Colombia's relations with Venezuela have fluctuated due to ideological differences between the two governments.[118] Colombia has offered humanitarian support with food and medicines to mitigate the shortage of supplies in Venezuela.[119] Colombia's Foreign Ministry said that all efforts to resolve Venezuela's crisis should be peaceful.[120] Colombia proposed the idea of the Sustainable Development Goals and a final document was adopted by the United Nations.[121] In February 2019, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro cut off diplomatic relations with Colombia after Colombian President Ivan Duque had helped Venezuelan opposition politicians deliver humanitarian aid to their country. Colombia recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country's legitimate president. In January 2020, Colombia rejected Maduro's proposal that the two countries restore diplomatic relations.[122]

Protests started on 28 April 2021 when the government proposed a tax bill which would greatly expand the range of the 19 percent value-added tax.[123] The 19 June 2022 election run-off vote ended in a win for former guerrilla, Gustavo Petro, taking 50.47% of the vote compared to 47.27% for independent candidate Rodolfo Hernández. The single-term limit for the country's presidency prevented president Iván Duque from seeking re-election. On 7 August 2022, Petro was sworn in, becoming the country's first leftist president.[124][125]

^ Correal, Urrego G. (1993). "Nuevas evidencias culturales pleistocenicas y megafauna en Colombia". Boletin de Arqueologia (8): 3–13. ^ Hoopes, John (1994). "Ford Revisited: A Critical Review of the Chronology and Relationships of the Earliest Ceramic Complexes in the New World, 6000-1500 B.C. (1994)". Journal of World Prehistory. 8 (1): 1–50. doi:10.1007/bf02221836. S2CID 161916440. ^ Van der Hammen, Thomas; Urrego, Gonzalo Correal (September 1978). "Prehistoric man of the Sabana de Bogotá: Data for an ecological prehistory". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 25 (1–2): 179–190. Bibcode:1978PPP....25..179V. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(78)90077-9. ^ Alberge, Dalya (29 November 2020). "Sistine Chapel of the ancients' rock art discovered in remote Amazon forest". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 June 2021. ^ Broadbent, Sylvia (1965). "Los Chibchas: organización socio-polític". Serie Latinoamericana. 5. ^ Álvaro Chaves Mendoza; Jorge Morales Gómez (1995). Los indios de Colombia (in Spanish). Vol. 7. Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 978-9978-04-169-7. ^ "Historia de Colombia: el establecimiento de la dominación española – Los Pueblos Indígenas del Territorio Colombiano" (in Spanish). banrepcultural.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2016. ^ Nicolás del Castillo Mathieu (March 1992). "La primera vision de las costas Colombianas, Repaso de Historia". Revista Credencial (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2008. ^ "Alonso de Ojeda" (in Spanish). biografiasyvidas.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014. ^ "Rodrigo de Bastidas" (in Spanish). biografiasyvidas.com. Retrieved 2 April 2014. ^ "Cristóbal Colón" (in Spanish). biografiasyvidas.com. Retrieved 2 April 2014. ^ "Vasco Núñez de Balboa" (in Spanish). biografiasyvidas.com. Retrieved 2 April 2014. ^ Vázquez, Trinidad Miranda (1976). La gobernación de Santa Marta (1570–1670) Vol. 232 (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-84-00-04276-9. ^ Plá, María del Carmen Borrego (1983). Cartagena de Indias en el siglo XVI. Vol. 288 (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-84-00-05440-3. ^ Francis, John Michael, ed. (2007). Invading Colombia: Spanish accounts of the Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada expedition of conquest Vol. 1. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02936-8. ^ Uribe, Jaime Jaramillo. "Perfil histórico de Bogotá." Historia crítica 1 (1989): 1. ^ Silvia Padilla Altamirano (1977). La encomienda en Popayán: tres estudios (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-84-00-03612-6. ^ Massimo Livi Bacci (2012). El dorado en el pantano (in Spanish). Marcial Pons Historia. ISBN 978-84-92820-65-8. ^ Ramírez, Natalia; Gutiérrez, Germán (2010). "Félix de Azara: Observaciones conductuales en su viaje por el Virreinato del Río de la Plata". Revista de historia de la psicología. 31 (4): 52–53. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016. ^ "El Dorado Legend Snared Sir Walter Raleigh". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2013. ^ "La Conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada: la interpretación de los siete mitos (III) – RESTALL, Matthew: Los siete mitos de la conquista española, Barcelona, 2004" (in Spanish). queaprendemoshoy.com/. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2016. ^ Jorge Augusto Gamboa M. "Las sociedades indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada bajo el dominio español" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ "Las plantas medicinales en la época de la colonia y de la independencia" (PDF) (in Spanish). colombiaaprende.edu.co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014. ^ a b Mayorga, Fernando (2002). "La propiedad de tierras en la Colonia: Mercedes, composición de títulos y resguardos indígenas". banrepcultural.org (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014. ^ a b Germán Colmenares. "Historia económica y órdenes de magnitud, Capítulo 1: La Formación de la Economía Colonial (1500–1740)" (in Spanish). banrepcultural.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2014. ^ a b Margarita González. "La política económica virreinal en el Nuevo Reino de Granada: 1750–1810" (PDF) (in Spanish). banrepcultural.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. ^ Domingo, Mariano Cuesta (2004). "Alonso de Santa Cruz, cartógrafo y fabricante de instrumentos náuticos de la Casa de Contratación" [Alonso de Santa Cruz, Cartographer and Maker of Nautical Instruments of the Spanish Casa de Contratación]. Revista Complutense de Historia de América (in Spanish). 30: 7–40. ^ John Huxtable Elliott (2007). Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America, 1492–1830. Yale University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-300-12399-9. ^ Shaw, Jeffrey M. (2019). Religion and Contemporary Politics: A Global Encyclopedia. p. 429. ISBN 9781440839337. ^ "Law VIII ("Royal Audiencia and Chancery of Santa Fe in the New Kingdom of Granada") of Title XV ("Of the Royal Audiencias and Chanceries of the Indies") of Book II" (PDF). congreso.gob.pe. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014. ^ Fernando Mayorga García; Juana M. Marín Leoz; Adelaida Sourdis Nájera (2011). El patrimonio documental de Bogotá, Siglos XVI – XIX: Instituciones y Archivos (PDF). Subdirección Imprenta Distrital – D.D.D.I. ISBN 978-958-717-064-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. ^ Julián Bautista Ruiz Rivera (1975). Encomienda y mita en Nueva Granada en el siglo XVII. Editorial CSIC Press. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 978-84-00-04176-2. ^ a b Jorge Cerdá Crespo (2010). Conflictos coloniales: la guerra de los nueve años 1739–1748 (in Spanish). Universidad de Alicante. ISBN 978-84-9717-127-4. ^ Génesis y desarrollo de la esclavitud en Colombia siglos XVI y XVII (in Spanish). Universidad del Valle. 2005. ISBN 978-958-670-338-3. ^ Alvaro Gärtner (2005). Los místeres de las minas: crónica de la colonia europea más grande de Colombia en el siglo XIX, surgida alrededor de las minas de Marmato, Supía y Riosucio. Universidad de Caldas. ISBN 978-958-8231-42-6. ^ Moñino, Yves; Schwegler, Armin (2002). Palenque, Cartagena y Afro-Caribe: historia y lengua. Walter de Gruyter. pp. vii–ix, 21–35. ISBN 978-3-11-096022-8. ^ "Palenque de San Basilio" (PDF) (in Spanish). urosario.edu.co. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Proceso de beatificación y canonización de San Pedro Claver. Edición de 1696. Traducción del latín y del italiano, y notas de Anna María Splendiani y Tulio Aristizábal S. J. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Universidad Católica del Táchira. 2002. ^ Valtierra, Ángel. 1964. San Pedro Claver, el santo que liberó una raza. ^ "La esclavitud negra en la América española" (in Spanish). gabrielbernat.es. 2003. ^ Villamar, Cuauhtemoc (March 2022). "El Galeón de Manila y el comercio de Asia: Encuentro de culturas y sistemas". Interacción Sino-Iberoamericana / Sino-Iberoamerican Interaction. 2 (1): 85–109. doi:10.1515/sai-2022-0008. S2CID 249318172. ^ Rivera, Julián Bautista Ruiz (1997). "Reformismo local en el nuevo Reino de Granada. Temas americanistas N° 13" (PDF) (in Spanish). pp. 80–98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014. ^ Jaime U. Jaramillo; Adolfo R. Maisel; Miguel M. Urrutia (1997). Transferring Wealth and Power from the Old to the New World: Monetary and Fiscal Institutions in the 17th Through the 19th Centuries – Chapter 12 (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02727-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Greshko, Michael. "Did This Spanish Shipwreck Change the Course of History?". National Geographic. ^ "José Celestino Mutis in New Granada: A life at the service of an Expedition (1760–1808)". Real Jardín Botánico. ^ Angela Perez-Mejia (2004). A Geography of Hard Times: Narratives about Travel to South America, 1780–1849 – Part I: The scholar and the baron: Voyage of the exact sciences. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6013-9. ^ John Wilton Appel (1994). Francisco José de Caldas: A Scientist at Work in Nueva Granada. American Philosophical Society. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-87169-845-2. ^ "Independencia de Colombia: ¿por qué se celebra el 20 de julio?" [Independence of Colombia: Why is it celebrated on 20 July?]. El País (in Spanish). 20 July 2017. ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018. ^ McFarlane, Anthony (January 1982). "El colapso de la autoridad española y la génesis de la independencia en la Nueva Granada". Revista Desarrollo y Sociedad (7): 99–120. doi:10.13043/dys.7.3. ^ Rodriguez Gómez, Juan Camilo. "La independencia del Socorro en la génesis de la emancipación colombiana" (in Spanish). banrepcultural.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017. ^ Gutiérrez Ardila, Daniel (December 2011). "Colombia y Haití: historia de un desencuentro (1819–1831)" [Colombia and Haití: History of a Misunderstanding (1819–1831)]. Secuencia (in Spanish) (81): 67–93. ^ Gutiérrez Escudero, Antonio. "Un precursor de la emancipación americana: Antonio Nariño y Álvarez" (PDF) (in Spanish). Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades 8.13 (2005). pp. 205–220. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Sourdis Nájera, Adelaida. "Independencia del Caribe colombiano 1810–1821" (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia – Edición 242. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2015. ^ Martínez Garnica, Armandao (2010). "Confederación de las Provincias Unidas de la Nueva Granada" (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia – Edición 244. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2015. ^ "Acta de la Federación de las Provincias Unidas de Nueva Granada" (in Spanish). 1811. ^ Ocampo López, Javier (1998). La patria boba. Cuadernillos de historia. Panamericana Editorial. ISBN 978-958-30-0533-6. ^ "Morillo y la reconquista, 1816–1819" (in Spanish). udea.edu.co. ^ Ocampo López, Javier (2006). Historia ilustrada de Colombia – Capítulo VI (in Spanish). Plaza y Janes Editores Colombia sa. ISBN 978-958-14-0370-7. ^ Cartagena de Indias en la independencia (PDF). Banco de la República. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ "Cronología de las independencias americanas" (in Spanish). cervantes.es. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018. ^ Gutiérrez Ramos, Jairo (2008). "La Constitución de Cádiz en la Provincia de Pasto, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, 1812–1822". Revista de Indias (in Spanish). Revista de Indias 68, no. 242. 68 (242): 222. doi:10.3989/revindias.2008.i242.640. ^ Alfaro Pareja; Francisco José (2013). La Independencia de Venezuela relatada en clave de paz: las regulaciones pacíficas entre patriotas y realistas (1810–1846) (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. ^ Alexander Walker (1822). (Gran) Colombia, relación geográfica, topográfica, agrícola, comercial y política de este país: Adaptada para todo lector en general y para el comerciante y colono en particular, Volume 1 (in Spanish). Banco de la República. ^ Sosa Abella, Guillermo (2009). "Los ciudadanos en la Constitución de Cúcuta – Citizenship in the Constitution of Cúcuta" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia (icanh). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015. ^ Mollien, Gaspard-Théodore, conde de, 1796–1872. "El viaje de Gaspard-Théodore Mollien por la República de Colombia en 1823. CAPÍTULO IX" (in Spanish). Biblioteca Virtual del Banco de la República. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2015.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) ^ "Avatares de una Joven República – 2. La Constitución de Cúcuta" (in Spanish). Universidad de Antioquia. ^ a b "Colombia profile - Timeline". BBC News. 27 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2023. ^ a b Blanco Blanco, Jacqueline (2007). "De la gran Colombia a la Nueva Granada, contexto histórico-político de la transición constitucional" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Militar Nueva Granada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ "Colombia". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 12 January 2022. ^ a b Edgar Arana. "Historia Constitucional Colombiana" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Libre Seccional Pereira. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2015. ^ Juan Fernando Londoño (2009). Partidos políticos y think tanks en Colombia (PDF) (in Spanish). International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. p. 129. ISBN 978-91-85724-73-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2015. ^ Aguilera, Miguel (1965). La Legislación y el derecho en Colombia. Historia extensa de Colombia. Vol. 14. Bogotá: Lemer. pp. 428–442. ^ Restrepo, Eduardo (2006). "Abolitionist arguments in Colombia". História Unisinos (in Spanish). 10 (3): 293–306. ^ "Constituciones que han existido en Colombia" (in Spanish). Banco de la República. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. ^ Gonzalo España (2013). El país que se hizo a tiros (in Spanish). Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Colombia. ISBN 978-958-8613-90-1. ^ "The 1903 Treaty and Qualified Independence". U.S. Library of Congress. ^ Beluche, Olmedo (2003). "The true history of the separation of 1903 – La verdadera historia de la separación de 1903" (PDF) (in Spanish). ARTICSA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2015. ^ "El tratado Urrutia-Thomson. Dificultades de política interna y exterior retrasaron siete años su ratificación" (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia. 2003. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2015. ^ Atehortúa Cruz; Adolfo León (2014). "El conflicto Colombo-Peruano – Apuntes acerca de su desarrollo e importancia histórica". Historia y Espacio (in Spanish). 3 (29): 51–78. doi:10.25100/hye.v3i29.1664. S2CID 252776167. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. ^ Alape, Arturo (1983). El Bogotazo: Memorias Del Olvido (in Spanish). Fundación Universidad Central. ^ Braun, Herbert (1987). Mataron a Gaitán: vida pública y violencia urbana en Colombia (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Centro Editorial. ISBN 978-958-17-0006-6. ^ Charles Bergquist; David J. Robinson (1997–2005). "Colombia". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2005. Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2006. On 9 April 1948, Gaitán was assassinated outside his law offices in downtown Bogotá. The assassination marked the start of a decade of bloodshed, called La Violencia (The Violence), which took the lives of an estimated 180,000 Colombians before it subsided in 1958. ^ Carlos Horacio Urán (1986). "Colombia y los Estados Unidos en la Guerra de Corea" (PDF) (in Spanish). The Kellogg Institute for International Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Atehortúa Cruz, Adolfo (2 February 2010). "El golpe de Rojas y el poder de los militares" [Rojas’ coup d’etat and the power of army men]. Folios (in Spanish). 1 (31): 33–48. doi:10.17227/01234870.31folios33.48. ^ Ayala Diago, César Augusto (2000). "Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, 100 años, 1900–1975" (in Spanish). Banco de la República. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017. ^ Alarcón Núñez, Óscar (2006). "1957–1974 El Frente Nacional" (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017. ^ ROJAS, Diana Marcela. La alianza para el progreso de Colombia. Análisis Político, [S.l.], v. 23, n. 70, p. 91–124, Sep. 2010. ISSN 0121-4705 ^ Ayala Diago, César Augusto (1999). "Frente Nacional: acuerdo bipartidista y alternación en el poder" (in Spanish). Revista Credencial Historia. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2017. ^ "El Frente Nacional" (in Spanish). banrepcultural.org. 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017. ^ a b Historical Commission on the Conflict and Its Victims (CHCV) (February 2015). "Contribution to an Understanding of the Armed Conflict in Colombia" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016. ^ Lilian Yaffe (3 October 2011). "Armed conflict in Colombia: analyzing the economic, social, and institutional causes of violent opposition" (in Spanish). icesi.edu.co. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013. ^ "Tomas y ataques guerrilleros (1965–2013)" (in Spanish). centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018. ^ Héctor Abad Faciolince (2006). Oblivion: A Memoir. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-53393-9. ^ "Oblivion: a memoir by Hector Abad wins Wola-Duke human rights book award". wola.org. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2016. ^ "First-class citizens: Father de Nicoló and the street kids of Colombia". iaf.gov. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016. ^ a b Historical Memory Group (2013). "Enough Already!" Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity (PDF) (in Spanish). The National Center for Historical Memory's (NCHM). ISBN 9789585760844. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Mario A. Murillo; Jesús Rey Avirama (2004). Colombia and the United States: war, unrest, and destabilization. Seven Stories Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-58322-606-3. ^ "The Colombian Cartels". WGBH educational foundation. Retrieved 25 May 2020. ^ "20 grandes cambios que generó la Constitución de 1991" (in Spanish). elpais.com.co. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2013. ^ "Colombian Constitution of 1991" (in Spanish). secretariasenado.gov.co. Retrieved 10 March 2014. ^ Mercado, Juan Guillermo (22 September 2013). "Desmovilización, principal arma contra las guerrillas" [Demobilization, main weapon against the guerrillas]. El Tiempo (in Spanish). ^ "Former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe Speaks at Yale SOM". Yale School of Management. 3 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2016. ^ "Colombia". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2015. (Archived 2015 edition) ^ "Oscar Morales and One Million Voices Against FARC". Movements.org. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013. ^ "Colombia's peace deals". altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017. ^ "Colombia referendum: Voters reject Farc peace deal". BBC News. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016. ^ "Plebiscito 2 octubre 2016 – Boletín Nacional No. 53". Registraduría Nacional de Estado Civil. 2 October 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016. ^ "Colombia signs new peace deal with Farc". BBC News. 24 November 2016. ^ Partlow, Joshua; Miroff, Nick (30 November 2016). "Colombia's congress approves historic peace deal with FARC rebels". The Washington Post. ^ "Nobel Lecture by Juan Manuel Santos, Oslo, 10 December 2016". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016. ^ "The Victims and Land Restitution Law" (PDF) (in Spanish). unidadvictimas.gov.co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2014. ^ "the Land Restitution Unit". restituciondetierras.gov.co. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2013. ^ Peters, Toni (12 October 2011). "Colombia has improved under Santos: Human Rights Watch". Colombia Reports. ^ "ABC Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz". Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016. ^ "Pope at Colombia prayer meeting for reconciliation weeps with victims". radiovaticana.va. 8 September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017. ^ "Colombia's president-elect Duque wants to 'unite country'". BBC News. 18 June 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2021. ^ "Iván Duque: Colombia's new president sworn into office". BBC News. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2021. ^ "Colombia and Venezuela restore diplomatic relations". BBC News. 11 August 2010. ^ "Colombia reitera ofrecimiento de ayuda humanitaria a Venezuela" [Colombia reiterates offer of humanitarian aid to Venezuela]. Presidencia.gov.co (in Spanish). 11 January 2018. ^ "Comunicado de prensa del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores" [Press release of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs]. Presidencia.gov.co (in Spanish). 2 June 2017. ^ Caballero, Paula (20 September 2016). "A Short History of the SDGS". Impakter.com. ^ "Colombia rejects Venezuelan proposal to resume diplomatic relations". reuters. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2021. ^ Guillermoprieto, Alma (22 July 2021). "Confrontation in Colombia | by Alma Guillermoprieto | The New York Review of Books". Retrieved 2 July 2021. ^ "Former guerrilla Gustavo Petro wins Colombian election to become first leftist president". the Guardian. 20 June 2022. ^ "Ex-rebel takes oath as Colombia's first left-wing president". www.aljazeera.com.

Cite error: There are <ref group=Note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Note}} template (see the help page).

- Stay safe

WARNING: Even though security in Colombia has increased significantly, violence linked to drug trafficking still affects a few, mainly rural, areas of the country. Specifically, kidnapping of foreign nationals for ransom still occurs from time to time. Visitors are urged to remain vigilant, especially outside major cities, and keep up to date with the latest government travel advisories....Read moreStay safeRead less

WARNING: Even though security in Colombia has increased significantly, violence linked to drug trafficking still affects a few, mainly rural, areas of the country. Specifically, kidnapping of foreign nationals for ransom still occurs from time to time. Visitors are urged to remain vigilant, especially outside major cities, and keep up to date with the latest government travel advisories....Read moreStay safeRead less WARNING: Even though security in Colombia has increased significantly, violence linked to drug trafficking still affects a few, mainly rural, areas of the country. Specifically, kidnapping of foreign nationals for ransom still occurs from time to time. Visitors are urged to remain vigilant, especially outside major cities, and keep up to date with the latest government travel advisories. Terrorist attacks continue — pay attention to warnings from local authorities.

Government travel advisories(Information last updated 17 Aug 2020)United Kingdom United States

WARNING: Even though security in Colombia has increased significantly, violence linked to drug trafficking still affects a few, mainly rural, areas of the country. Specifically, kidnapping of foreign nationals for ransom still occurs from time to time. Visitors are urged to remain vigilant, especially outside major cities, and keep up to date with the latest government travel advisories. Terrorist attacks continue — pay attention to warnings from local authorities.

Government travel advisories(Information last updated 17 Aug 2020)United Kingdom United StatesColombia has suffered from a terrible reputation as a dangerous and violent country but the situation has improved dramatically since the 1980s and 1990s. Colombia is on the path to recovery, and Colombians are very proud of the progress they have made. These days, Colombia is generally safe to visit, with the violent crime rate being lower than that in Mexico or Brazil, as long as you avoid poorer areas of the cities at night, and do not venture off the main road into the jungle where guerrillas are likely to be hiding.

The security situation varies greatly around the country. The Travel Risk Map covers Colombia and shows the current safety levels throughout the country. Most jungle regions are not safe to visit, but the area around Leticia is very safe, and the areas around Santa Marta are OK. No one should visit the Darien Gap at the border with Panama (in the north of Chocó), Putumayo or Caquetá, which are very dangerous, active conflict zones. Other departments with significant rural violence include the Atlantic departments of Chocó, Cauca, and Valle del Cauca; eastern Meta, Vichada, and Arauca in the east; and all Amazonian departments except for Amazonas. That's not to say that these departments are totally off-limits—just be sure you are either traveling with locals who know the area or sticking to cities and tourist destinations. In general, if you stick to the main roads between major cities and do not wander off into remote parts of the jungle, you are unlikely to run into trouble, and you are much more likely to encounter a Colombian army checkpoint than an illegal guerrilla roadblock.

Landmines Graffiti on a wall in Bogota

Graffiti on a wall in BogotaColombia is one of the most mine-affected countries in the world. So don't walk around blithely through the countryside without consulting locals. Land mines are found in 31 out of Colombia's 32 departments, and new ones are planted every day by guerrillas, paramilitaries, and drug traffickers.

ParamilitariesThere was an agreement in 2005 with the government which resulted in the disarmament of some of the paramilitaries. However they are still active in drug business, extortion rackets, and as a political force. They do not target tourists specifically, but running up against an illegal rural roadblock in more dangerous departments is possible.

KidnappingsAt the turn of the millennium Colombia had the highest rates of kidnapping in the world, a result of being one of the most cost-effective ways of financing for the guerrillas of the FARC and the ELN and other armed groups. Fortunately, the security situation has much improved and the groups involved are today much weakened, with the number of kidnappings dropping from 3,000 in 2000 down to 205 cases in 2016. Today kidnappings are still a problem in some southern departments like Valle del Cauca, Cauca, and Caquetá. Colombian law makes the payment of ransom illegal, therefore the police may not be informed in some circumstances.

GuerrillasThe guerrilla movements which include FARC and ELN guerrillas are still operational, though they are greatly weakened compared to the 1990s as the Colombian army has killed most of their leaders. These guerrillas operate mainly in rural parts of southern, southeastern and northwestern Colombia, although they have a presence in 30 out of the country's 32 departments. Big cities hardly ever see guerrilla activity these days. Even in rural areas, if you stick to the main roads between major cities and do not wander off the beaten track, you are far more likely to encounter soldiers from the Colombian army than guerrillas. River police, highway police, newspapers, and fellow travelers can be a useful source of information off-the-beaten-path.

Crime Colombian police officers next to a patrol car

Colombian police officers next to a patrol carThe crime rate in Colombia has been significantly reduced since its peak in the late 1980s and 1990s, with the police having arrested or killed many of the important leaders of the drug cartels. However, major urban centers and the countryside of Colombia still have very high violent crime rates, comparable to blighted cities in the United States, and crime has been on the increase. In the downtown areas of most cities (which rarely coincide with the wealthy parts of town) violent crime is not rare; poor sections of cities can be quite dangerous for someone unfamiliar with their surroundings. Taxi crime is a very serious danger in major cities, so always request taxis by phone or app, rather than hailing them off the street—it costs the same and your call will be answered rapidly. Official taxi ranks are safe as well (airports, bus terminals, shopping malls).

DrugsLocal consumption is low, and penalties are draconian, owing to the nation's well-known largely successful fight against some of history's most powerful and dangerous traffickers. Remember that the drug trade in Colombia has ruined many innocent citizens' lives and dragged the country's reputation through the mud.

Marijuana is illegal to buy and sell, although officially you can carry up to 20 grams without being charged for it. Police will tolerate you having a few grams of this drug on your person, but you are flirting with danger if you carry much more. Especially in small towns, it is not always the police you have to deal with, but vigilantes. They often keep the peace in towns, and they have a very severe way of dealing with problems.

Scopolamine is an extremely dangerous drug from an Andean flowering tree, which is almost exclusively used for crime, and nearly all the world's incidents of such use take place in Colombia. Essentially a mind control drug (once experimented with as an interrogation device by the CIA), victims become extremely open to suggestion and are "talked into" ATM withdrawals, turning over belongings, letting criminals into their apartments, etc., all while maintaining an outward appearance of more or less sobriety. After affects include near total amnesia of what happened, as well as potential for serious medical problems. The most talked about method of getting drugged with scopolamine is that of powder blown off paper, e.g., someone walks up to you (with cotton balls in their nose to prevent blowback) and asks for help with a map, before blowing the drugs into your face. But by far the most common method is by drugging drinks at a bar. To be especially safe, abandon drinks if they've been left unattended. While a pretty rare problem, it's an awfully scary one, and happens most often in strip clubs or other establishments involving sex workers.