Context of Chechnya

Chechnya, officially the Chechen Republic, is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, close to the Caspian Sea. The republic forms a part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; with the Russian republics of Dagestan, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia-Alania to its east, north, and west; and with Stavropol Krai to its northwest.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Checheno-Ingush ASSR split into two parts: the Republic of Ingushetia and the Chechen Republic. The latter proclaimed the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, which sought independence, while the former sided with Russia. Following the First Chechen War of 1994–1996 with Russia, Chechnya gained de facto independence as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, although de jure it remained a part of Russia. Russian federal control was restored in the Secon...Read more

Chechnya, officially the Chechen Republic, is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, close to the Caspian Sea. The republic forms a part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; with the Russian republics of Dagestan, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia-Alania to its east, north, and west; and with Stavropol Krai to its northwest.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Checheno-Ingush ASSR split into two parts: the Republic of Ingushetia and the Chechen Republic. The latter proclaimed the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, which sought independence, while the former sided with Russia. Following the First Chechen War of 1994–1996 with Russia, Chechnya gained de facto independence as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, although de jure it remained a part of Russia. Russian federal control was restored in the Second Chechen War of 1999–2009, with Chechen politics being dominated by a former rebel Akhmad Kadyrov, and later his son Ramzan Kadyrov.

The republic covers an area of 17,300 square kilometres (6,700 square miles), with a population of over 1.5 million residents as of 2021. It is home to the indigenous Chechens, part of the Nakh peoples, and of primarily Muslim faith. Grozny is the capital and largest city.

More about Chechnya

- Population 1492992

- Area 16165

- Origin of Chechnya's populationRead less

According to Leonti Mroveli, the 11th-century Georgian chronicler, the word Caucasian is derived from the Nakh ancestor Kavkas.[1] According to George Anchabadze of Ilia State University:

The Vainakhs are the ancient natives of the Caucasus. It is noteworthy, that according to the genealogical table drawn up by Leonti Mroveli, the legendary forefather of the Vainakhs was "Kavkas", hence the name Kavkasians, one of the ethnicons met in the ancient Georgian written sources, signifying the ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush. As appears from the above, the Vainakhs, at least by name, are presented as the most "Caucasian" people of all the Caucasians (Caucasus – Kavkas – Kavkasians) in the Georgian historical tradition.[2][3]

American linguist Johanna Nichols "has used language to connect the modern people of the Caucasus region to the ancient farmers of the Fertile Crescent" and her research suggests that "farmers of the region were proto-Nakh-Daghestanians". Nichols stated: "The Nakh–Dagestanian languages are the closest thing we have to a direct continuation of the cultural and linguistic community that gave rise to Western civilisation."[4]

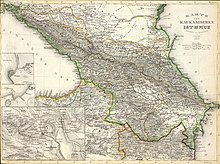

Prehistory Map of the Caucasian isthmus by J. Grassl, 1856

Map of the Caucasian isthmus by J. Grassl, 1856Traces of human settlement dating back to 40,000 BCE were found near Lake Kezanoi. Cave paintings, artifacts, and other archaeological evidence indicate continuous habitation for some 8,000 years.[5] People living in these settlements used tools, fire, and clothing made of animal skins.[5]

The Caucasian Epipaleolithic and early Caucasian Neolithic era saw the introduction of agriculture, irrigation, and the domestication of animals in the region.[4] Settlements near Ali-Yurt and Magas, discovered in modern times, revealed tools made out of stone: stone axes, polished stones, stone knives, stones with holes drilled in them, clay dishes etc. Settlements made out of clay bricks were discovered in the plains. In the mountains there were settlements made from stone and surrounded by walls; some of them dated back to 8000 BCE.[6][full citation needed] This period also saw the appearance of the wheel (3000 BCE), horseback riding, metal works (copper, gold, silver, iron), dishes, armor, daggers, knives and arrow tips in the region. The artifacts were found near Nasare-Cort, Muzhichi, Ja-E-Bortz (alternatively known as Surkha-khi), Abbey-Gove (also known as Nazran or Nasare).[6]

Pre-imperial eraThe German scientist Peter Simon Pallas believed that the Vainakh people (Chechens and Ingush) were the direct descendants from Alania.[7][better source needed] In 1239, the Alania capital of Maghas and the Alan confederacy of the Northern Caucasian highlanders, nations, and tribes was destroyed by Batu Khan (a Mongol leader and a grandson of Genghis Khan).

According to the missionary Pian de Carpine, a part of the Alans had successfully resisted a Mongol siege on a mountain for 12 years:[8][full citation needed]

When they (the Mongols) begin to besiege a fortress, they besiege it for many years, as it happens today with one mountain in the land of the Alans. We believe they have been besieging it for twelve years and they (the Alans) put up courageous resistance and killed many Tatars, including many noble ones.

— Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, report from 1250This twelve year old siege is not found in any other report, however the Russian historian A. I. Krasnov connected this battle with two Chechen folktales he recorded in 1967 that spoke of an old hunter named Idig who with his companions defended the Dakuoh mountain for 12 years against Tatar-Mongols. He also reported to have found several arrowheads and spears from the 13th century near the very mountain at which the battle took place:[9]

The next year, with the onset of summer, the enemy hordes came again to destroy the highlanders. But even this year they failed to capture the mountain, on which the brave Chechens settled down. The battle lasted twelve years. The main wealth of the Chechens – livestock – was stolen by the enemies. Tired of the long years of hard struggle, the Chechens, believing the assurances of mercy by the enemy, descended from the mountain, but the Mongol-Tatars treacherously killed the majority, and the rest were taken into slavery. This fate was escaped only by Idig and a few of his companions who did not trust the nomads and remained on the mountain. They managed to escape and leave Mount Dakuoh after 12 years of siege.

— Amin Tesaev, "The Legend and Struggle of the Chechen Hero Idig (1238–1250)"In the 14th and 15th centuries, there was frequent warfare between the Chechens, Tamerlane and Tokhtamysh, culminating in the Battle of the Terek River (see Tokhtamysh–Timur war). The Chechen tribes built fortresses, castles, and defensive walls, protecting the mountains from the invaders. Part of the lowland tribes were occupied by Mongols. However, during the mid-14th century a strong Chechen Princedom called Simsim emerged under Khour II, a Chechen king that led the Chechen politics and wars. He was in charge of an army of Chechens against the rogue warlord Mamai and defeated him in the Battle of Tatar-tup in 1362. The kingdom of Simsim was almost destroyed during the Timurid invasion of the Caucasus, when Khour II allied himself with the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh in the Battle of the Terek River. Timur sought to punish the highlanders for their allegiance to Tokhtamysh and as a consequence invaded Simsim in 1395.[10]

The 16th century saw the first Russian involvement in the Caucasus. In 1558, Temryuk of Kabarda sent his emissaries to Moscow requesting help from Ivan the Terrible against the Vainakh tribes. Ivan the Terrible married Temryuk's daughter Maria Temryukovna. An alliance was formed to gain the ground in the central Caucasus for the expanding Tsardom of Russia against stubborn Vainakh defenders. Chechnya was a nation in the Northern Caucasus that fought against foreign rule continually since the 15th century. Several Chechen leaders such as the 17th century Mehk-Da Aldaman Gheza led the Chechen politics and fought off encroachments of foreign powers. He defended the borders of Chechnya from invasions of Kabardinians and Avars during the Battle of Khachara in 1667.[11] The Chechens converted over the next few centuries to Sunni Islam, as Islam was associated with resistance to Russian encroachment.[12][13]

Imperial rule Captured Imam Shamil before the commander-in-chief Prince Bariatinsky on 25 August 1859; painting by Theodor Horschelt

Captured Imam Shamil before the commander-in-chief Prince Bariatinsky on 25 August 1859; painting by Theodor HorscheltPeter the Great first sought to increase Russia's political influence in the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea at the expense of Safavid Persia when he launched the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723. Russian forces succeeded in taking much of the Caucasian territories from Iran for several years.[14]

As the Russians took control of the Caspian corridor and moved into Persian-ruled Dagestan, Peter's forces ran into mountain tribes. Peter sent a cavalry force to subdue them, but the Chechens routed them.[14] In 1732, after Russia already ceded back most of the Caucasus to Persia, now led by Nader Shah, following the Treaty of Resht, Russian troops clashed again with Chechens in a village called Chechen-aul along the Argun River.[14] The Russians were defeated again and withdrew, but this battle is responsible for the apocryphal story about how the Nokchi came to be known as "Chechens" – the people ostensibly named for the place the battle had taken place. The name Chechen was however already used since as early as 1692.[14]

Under intermittent Persian rule since 1555, in 1783 the eastern Georgians of Kartl-Kakheti led by Erekle II and Russia signed the Treaty of Georgievsk. According to this treaty, Kartl-Kakheti received protection from Russia, and Georgia abjured any dependence on Iran.[15] In order to increase its influence in the Caucasus and to secure communications with Kartli and other Christian regions of the Transcaucasia which it considered useful in its wars against Persia and Turkey, the Russian Empire began conquering the Northern Caucasus mountains. The Russian Empire used Christianity to justify its conquests, allowing Islam to spread widely because it positioned itself as the religion of liberation from tsardom, which viewed Nakh tribes as "bandits".[16] The rebellion was led by Mansur Ushurma, a Chechen Naqshbandi (Sufi) sheikh—with wavering military support from other North Caucasian tribes. Mansur hoped to establish a Transcaucasus Islamic state under sharia law. He was unable to fully achieve this because in the course of the war he was betrayed by the Ottomans, handed over to Russians, and executed in 1794.[17]

Following the forced ceding of the current territories of Dagestan, most of Azerbaijan, and Georgia by Persia to Russia, following the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813 and its resultant Treaty of Gulistan, Russia significantly widened its foothold in the Caucasus at the expense of Persia.[18] Another successful Caucasus war against Persia several years later, starting in 1826 and ending in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay, and a successful war against Ottoman Turkey in 1828 and 1829, enabled Russia to use a much larger portion of its army in subduing the natives of the North Caucasus.

Chechen artillerymen

Chechen artillerymenThe resistance of the Nakh tribes never ended and was a fertile ground for a new Muslim-Avar commander, Imam Shamil, who fought against the Russians from 1834 to 1859 (see Murid War). In 1859, Shamil was captured by Russians at aul Gunib. Shamil left Baysangur of Benoa,[19] a Chechen with one arm, one eye, and one leg, in charge of command at Gunib. Baysangur broke through the siege and continued to fight Russia for another two years until he was captured and killed by Russians. The Russian tsar hoped that by sparing the life of Shamil, the resistance in the North Caucasus would stop, but it did not. Russia began to use a colonization tactic by destroying Nakh settlements and building Cossack defense lines in the lowlands. The Cossacks suffered defeat after defeat and were constantly attacked by mountaineers, who were robbing them of food and weaponry.

The tsarists' regime used a different approach at the end of the 1860s. They offered Chechens and Ingush to leave the Caucasus for the Ottoman Empire (see Muhajir (Caucasus)). It is estimated that about 80% of Chechens and Ingush left the Caucasus during the deportation. It weakened the resistance which went from open warfare to insurgent warfare. One of the notable Chechen resistance fighters at the end of the 19th century was a Chechen abrek Zelimkhan Gushmazukaev and his comrade-in-arms Ingush abrek Sulom-Beck Sagopshinski. Together they built up small units which constantly harassed Russian military convoys, government mints, and government post-service, mainly in Ingushetia and Chechnya. Ingush aul Kek was completely burned when the Ingush refused to hand over Zelimkhan. Zelimkhan was killed at the beginning of the 20th century. The war between Nakh tribes and Russia resurfaced during the times of the Russian Revolution, which saw the Nakh struggle against Anton Denikin and later against the Soviet Union.

On 21 December 1917, Ingushetia, Chechnya, and Dagestan declared independence from Russia and formed a single state: "United Mountain Dwellers of the North Caucasus" (also known as the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus) which was recognized by major world powers. The capital of the new state was moved to Temir-Khan-Shura (Dagestan).[20][21] Tapa Tchermoeff, a prominent Chechen statesman, was elected the first prime minister of the state. The second prime minister elected was Vassan-Girey Dzhabagiev, an Ingush statesman, who also was the author of the constitution of the republic in 1917, and in 1920 he was re-elected for the third term. In 1921 the Russians attacked and occupied the country and forcibly absorbed it into the Soviet state. The Caucasian war for independence restarted, and the government went into exile.[22]

Soviet ruleDuring Soviet rule, Chechnya and Ingushetia were combined to form the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In the 1930s, Chechnya was flooded with many Ukrainians fleeing a famine. As a result, many of the Ukrainians settled in Chechen-Ingush ASSR permanently and survived the famine.[23] Although over 50,000 Chechens and over 12,000 Ingush were fighting against Nazi Germany on the front line (including Heroes of the USSR: Abukhadzhi Idrisov, Khanpasha Nuradilov, Movlid Visaitov), and although Nazi German troops advanced as far as the Ossetian ASSR city of Ordzhonikidze and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR city of Malgobek after capturing half of the Caucasus in less than a month, Chechens and Ingush were falsely accused as Nazi supporters and entire nations were deported during Operation Lentil to the Kazakh SSR (later Kazakhstan) in 1944 near the end of World War II where over 60% of Chechen and Ingush populations perished.[24][25] American historian Norman Naimark writes:

Troops assembled villagers and townspeople, loaded them onto trucks – many deportees remembered that they were Studebakers, fresh from Lend-Lease deliveries over the Iranian border – and delivered them at previously designated railheads. ... Those who could not be moved were shot. ... [A] few fighters aside, the entire Chechen and Ingush nations, 496,460 people, were deported from their homeland.[26]

The deportation was justified by the materials prepared by NKVD officer Bogdan Kobulov accusing Chechens and Ingush in a mass conspiracy preparing rebellion and providing assistance to the German forces. Many of the materials were later proven to be fabricated.[27] Even distinguished Red Army officers who fought bravely against Germans (e.g. the commander of 255th Separate Chechen-Ingush regiment Movlid Visaitov, the first to contact American forces at Elbe river) were deported.[28] There is a theory that the real reason why Chechens and Ingush were deported was the desire of Russia to attack Turkey, an anti-communist country, as Chechens and Ingush could impede such plans.[16] In 2004, the European Parliament recognized the deportation of Chechens and Ingush as an act of genocide.[29]

The territory of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was divided between Stavropol Krai (where Grozny Okrug was formed), the Dagestan ASSR, the North Ossetian ASSR, and the Georgian SSR.

The Chechens and Ingush were allowed to return to their land after 1956 during de-Stalinisation under Nikita Khrushchev[24] when the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was restored but with both the boundaries and ethnic composition of the territory significantly changed. There were many (predominantly Russian) migrants from other parts of the Soviet Union, who often settled in the abandoned family homes of Chechens and Ingushes. The republic lost its Prigorodny District which transferred to North Ossetian ASSR but gained predominantly Russian Naursky District and Shelkovskoy District that is considered the homeland for Terek Cossacks.

The Russification policies towards Chechens continued after 1956, with Russian language proficiency required in many aspects of life to provide Chechens better opportunities for advancement in the Soviet system.[16]

On 26 November 1990, the Supreme Council of Chechen-Ingush ASSR adopted the "Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Chechen-Ingush Republic". This declaration was part of the reorganisation of the Soviet Union. This new treaty was to be signed 22 August 1991, which would have transformed 15 republic states into more than 80. The 19–21 August 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt led to the abandonment of this reorganisation.[30]

With the impending dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, an independence movement, the Chechen National Congress, was formed, led by ex-Soviet Air Force general and new Chechen President Dzhokhar Dudayev. It campaigned for the recognition of Chechnya as a separate nation. This movement was opposed by Boris Yeltsin's Russian Federation, which argued that Chechnya had not been an independent entity within the Soviet Union—as the Baltic, Central Asian, and other Caucasian states such as Georgia had—but was part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and hence did not have a right under the Soviet constitution to secede. It also argued that other republics of Russia, such as Tatarstan, would consider seceding from the Russian Federation if Chechnya were granted that right. Finally, it argued that Chechnya was a major hub in the oil infrastructure of Russia and hence its secession would hurt the country's economy and energy access.[citation needed]

During the Chechen Revolution, the Soviet Chechen leader Doku Zavgayev was overthrown and Dzhokhar Dudayev seized power. On 1 November 1991, Dudaev's Chechnya issued a unilateral declaration of independence. In the ensuing decade, the territory was locked in an ongoing struggle between various factions, usually fighting unconventionally.

Chechen Wars and brief independence A Chechen man prays during the Battle of Grozny.

A Chechen man prays during the Battle of Grozny.The First Chechen War took place from 1994 to 1996, when Russian forces attempted to regain control over Chechnya. Despite overwhelming numerical superiority in men, weaponry, and air support, the Russian forces were unable to establish effective permanent control over the mountainous area due to numerous successful full-scale battles and insurgency raids. The Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis in 1995 shocked the Russian public.

Dzhokhar Dudayev

Dzhokhar Dudayev Aslan Maskhadov

Aslan MaskhadovIn April 1996 the first democratically elected president of Chechnya, Dzhokhar Dudayev, was killed by Russian forces using a booby trap bomb and a missile fired from a warplane after he was located by triangulating the position of a satellite phone he was using.[31]

The widespread demoralisation of the Russian forces in the area and a successful offensive to re-take Grozny by Chechen rebel forces led by Aslan Maskhadov prompted Russian President Boris Yeltsin to declare a ceasefire in 1996, and sign a peace treaty a year later that saw a withdrawal of Russian forces.[32]

After the war, parliamentary and presidential elections took place in January 1997 in Chechnya and brought to power new President Aslan Maskhadov, chief of staff and prime minister in the Chechen coalition government, for a five-year term. Maskhadov sought to maintain Chechen sovereignty while pressing the Russian government to help rebuild the republic, whose formal economy and infrastructure were virtually destroyed.[33] Russia continued to send money for the rehabilitation of the republic; it also provided pensions and funds for schools and hospitals. Nearly half a million people (40% of Chechnya's prewar population) had been internally displaced and lived in refugee camps or overcrowded villages.[34][page needed] There was an economic downturn. Two Russian brigades were permanently stationed in Chechnya.[34]

Cadets of the Ichkeria Chechen national guard 1999.

Cadets of the Ichkeria Chechen national guard 1999.In light of the devastated economic structure, kidnapping emerged as the principal source of income countrywide, procuring over US$200 million during the three-year independence of the chaotic fledgling state,[35] although victims were rarely killed.[36] In 1998, 176 people were kidnapped, 90 of whom were released, according to official accounts. President Maskhadov started a major campaign against hostage-takers, and on 25 October 1998, Shadid Bargishev, Chechnya's top anti-kidnapping official, was killed in a remote-controlled car bombing. Bargishev's colleagues then insisted they would not be intimidated by the attack and would go ahead with their offensive. Political violence and religious extremism, blamed on "Wahhabism", was rife. In 1998, Grozny authorities declared a state of emergency. Tensions led to open clashes between the Chechen National Guard and Islamist militants, such as the July 1998 confrontation in Gudermes.

A Chechen fighter stands near the government palace building during a short lull in fighting in Grozny, Chechnya.

A Chechen fighter stands near the government palace building during a short lull in fighting in Grozny, Chechnya.The War of Dagestan began on 7 August 1999, during which the Islamic International Peacekeeping Brigade (IIPB) began an unsuccessful incursion into the neighboring Russian republic of Dagestan in favor of the Shura of Dagestan which sought independence from Russia.[37] In September, a series of apartment bombs that killed around 300 people in several Russian cities, including Moscow, were blamed on the Chechen separatists.[24] Some journalists contested the official explanation, instead blaming the Russian Secret Service for blowing up the buildings to initiate a new military campaign against Chechnya.[38] In response to the bombings, a prolonged air campaign of retaliatory strikes against the Ichkerian regime and a ground offensive that began in October 1999 marked the beginning of the Second Chechen War. Much better organized and planned than the First Chechen War, the Russian armed forces took control of most regions. The Russian forces used brutal force, killing 60 Chechen civilians during a mop-up operation in Aldy, Chechnya on 5 February 2000. After the re-capture of Grozny in February 2000, the Ichkerian regime fell apart.[39]

Post-war reconstruction and insurgencyThe neutrality of this section is disputed. (February 2016) Postage stamp issued in 2009 by the Russian Post dedicated to Chechnya

Postage stamp issued in 2009 by the Russian Post dedicated to Chechnya Minutka Square, Grozny

Minutka Square, GroznyChechen rebels continued to fight Russian troops and conduct terrorist attacks.[40][page needed] In October 2002, 40–50 Chechen rebels seized a Moscow theater and took about 900 civilians hostage.[24] The crisis ended with 117 hostages and up to 50 rebels dead, mostly due to an unknown aerosol pumped into the building by Russian special forces to incapacitate the people inside.[41][42][43]

In response to the increasing terrorism, Russia tightened its grip on Chechnya and expanded its anti-terrorist operations throughout the region. Russia installed a pro-Russian Chechen regime. In 2003, a referendum was held on a constitution that reintegrated Chechnya within Russia but provided limited autonomy. According to the Chechen government, the referendum passed with 95.5% of the votes and almost 80% turnout.[44] The Economist was skeptical of the results, arguing that "few outside the Kremlin regard the referendum as fair".[45]

In September 2004, separatist rebels occupied a school in the town of Beslan, North Ossetia, demanding recognition of the independence of Chechnya and a Russian withdrawal. 1,100 people (including 777 children) were taken hostage. The attack lasted three days, resulting in the deaths of over 331 people, including 186 children.[24][46][47][48] After the 2004 school siege, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced sweeping security and political reforms, sealing borders in the Caucasus region and revealing plans to give the central government more power. He also vowed to take tougher action against domestic terrorism, including preemptive strikes against Chechen separatists.[24] In 2005 and 2006, separatist leaders Aslan Maskhadov and Shamil Basayev were killed.

Since 2007, Chechnya has been governed by Ramzan Kadyrov. Kadyrov's rule has been characterized by high-level corruption, a poor human rights record, widespread use of torture, and a growing cult of personality.[49][50] Allegations of anti-gay purges in Chechnya were initially reported on 1 April 2017.

In April 2009, Russia ended its counter-terrorism operation and pulled out the bulk of its army.[51] The insurgency in the North Caucasus continued even after this date. The Caucasus Emirate had fully adopted the tenets of a Salafist jihadist group through its strict adherence to the Sunni Hanbali obedience to the literal interpretation of the Quran and the Sunnah.[52]

The Chechen government has been outspoken in its support for the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, where a Chechen military force, the Kadyrovtsy, which is under Kadyrov's personal command, has played a leading role, notably in the Siege of Mariupol.[53] Meanwhile, a substantial number of Chechen separatists have allied themselves to the Ukrainian cause and are fighting a mutual Russian enemy in the Donbas.[54] In June 2022, the US State Department advised citizens not to travel to Chechnya, due to terrorism, kidnapping, and risk of civil unrest.[55]

^ The work of Leonti Mroveli: "The history of the Georgian Kings" dealing with the history of Georgia and the Caucasus since ancient times to the 5th century AD, is included in medieval code of Georgian annals "Kartlis Tskhovreba". ^ "An Essay on the History of the Vainakh People. On the origin of the Vainakhs". Caucasian Knot. 14 January 2004. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023. ^ Anchabadze, George (2009) [first edition 2001]. The Vainakhs (the Chechen and Ingush) (PDF). Tbilisi: Caucasian House. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012. ^ a b Wuethrich, Bernice (19 May 2000). "Peering into the Past, With Words". Science. 288 (5469): 1158. doi:10.1126/science.288.5469.1158. S2CID 82205296. ^ a b Jaimoukha, Amjad M. (1 March 2005). The Chechens: a handbook (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Retrieved 14 August 2009. ^ a b N. D. Kodzoev. History of Ingush nation. ^ Sampiyev, Hasan. Страна башен [Tower country]. Ингушетия.Ru. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2014. ^ Tesaev, Amin (2020). "К личности и борьбе чеченского героя идига (1238–1250 гг.)". {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) ^ Krasnov, A. I. Копье Тебулос-Мта. Вокруг света. 9: 29. ^ Tesaev, Amin (2018). "Симсим". Рефлексия. 2: 61–67. ^ "Предводитель Гази Алдамов, или Алдаман ГIеза (Амин Тесаев) / Проза.ру". proza.ru. ^ Tsaroïeva, Mariel (2005). Anciennes croyances des Ingouches et des Tchétchènes: peuples du Caucase du Nord (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-1792-2. ^ Ilyasov, Lecha; Ziya Bazhayev Charity Foundation (2009). The Diversity of the Chechen Culture: From Historical Roots to the Present (PDF). UNESCO Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. ISBN 978-5-904549-02-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2010. ^ a b c d Schaefer, Robert W. (2010). The Insurgency in Chechnya and the North Caucasus: From Gazavat to Jihad. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313386343. Retrieved 25 December 2014. ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (20 December 2011). Iran at War: 1500–1988. Osprey Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781780962214. Retrieved 25 December 2014.[dead link] ^ a b c "The Ingush People". Linguistics.berkeley.edu. 28 November 1992. Retrieved 14 March 2014. ^ John Frederick Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus, London, Curzon Press, 1999, p. 49. ^ Cohen, Ariel (1998). Russian Imperialism: Development and Crisis. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780275964818. Retrieved 25 December 2014. ^ "Человек из камня Байсангур Беноевский". 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2014 – via YouTube. ^ "Independent Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus". Countries & Territories since 1900. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023. ^ "Общественное движение чеченский комитет национального спасения". Savechechnya.com. 24 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014. ^ "Вассан-Гирей Джабагиев". Vainah.info. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014. ^ Umarova, Amina (23 November 2013). "Chechnya's Forgotten Children of the Holodomor". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 14 March 2014. ^ a b c d e f Lieven, Dominic. "Russia: Chechnya". Microsoft Encarta 2008. Microsoft. ^ "Remembering Stalin's deportations". BBC News. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2013. ^ Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press, 2001, pp. 96–97. ^ Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev. Time of darkness. Moscow, 2003, ISBN 5-85646-097-9, pp. 205–206. ^ Bugay 1996, p. 106. ^ "Chechnya: European Parliament recognizes the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. ^ James Hughes. "The Peace Process in Chechnya", in Richard Sakwa (ed.), Chechnya: From Past to Future, p. 271. ^ "'Dual attack' killed president". BBC. 21 April 1999. Retrieved 1 January 2016. ^ "Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty archive". friends-partners.org. Friends & Partners. 12 May 1997. part I. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2016. ^ "Chechnya [Russia] (2003)". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. ^ a b Alex Goldfarb and Marina Litvinenko. Death of a Dissident: The Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the Return of the KGB. New York: Free Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4165-5165-2. ^ Tishkov, Valery. Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, p. 114. ^ "Four Western hostages beheaded in Chechnya". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 December 2002. ^ Harrigan, Steve. "Moscow again plans wider war in Dagestan". CNN. 19 August 1999. Retrieved 23 April 2013. ^ "Context of 'September 13, 1999: Second Moscow Apartment Bombing Kills 118; Chechen Rebels Blamed'". History Commons. Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 April 2013. ^ "Gay Chechens flee threats, beatings and exorcism". BBC News. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018. ^ Andrew Meier (2005). Chechnya: To the Heart of a Conflict. New York: W. W. Norton ^ "Gas 'killed Moscow hostages'". BBC News. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2013. ^ "Moscow court begins siege claims". BBC News. 24 December 2002. ^ "Moscow hostage relatives await news". BBC News. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 30 May 2011. ^ Aris, Ben (24 March 2003). "Boycott call in Chechen poll ignored". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2013. ^ "Putin's proposition". The Economist. 25 March 2003. Retrieved 22 April 2013. ^ "August 31, 2006: Beslan – Two Years On". Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009. ^ "Putin meets angry Beslan mothers". BBC News. Retrieved 23 April 2013. ^ "The children of Beslan five years on". BBC News. Retrieved 23 April 2013. ^ "Ramzan Kadyrov: The warrior king of Chechnya". The Independent. 4 January 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2016. ^ "Kadyrov's Power and Cult of Personality Grows". Jamestown. Retrieved 1 January 2016. ^ "Russia 'ends Chechnya operation'". BBC News. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2009. ^ "Salafist-Takfiri Jihadism: the Ideology of the Caucasus Emirate". International Institute for Counter-Terrorism. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2019. ^ Cranny-Evans, Sam (4 November 2022). "The Chechens: Putin's Loyal Foot Soldiers". Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies. Retrieved 23 May 2023. ^ "Chechen volunteer fighters back up Ukraine's Russian resistance". ABC News. Retrieved 14 August 2023. ^ "Russia Travel Advisory". Department of State. United States.