Casablanca (Arabic: الدار البيضاء, romanized: ad-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, [adˈdaːru ɫbajdˤaːʔ], lit. 'White House') is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business center. Located on the Atlantic coast of the Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a population of about 3.71 million in the urban area, and over 4.27 million in Greater Casablanca, making it the most populous city in the Maghreb region, and the eighth-largest in the Arab world.

Casablanca is Morocco's chief port, with the Port of Casablanca being one of the largest artificial ports in Africa, and the third-largest port in North Africa, after Tanger-Med (40 km (25 mi) east of Tangier) and Port Said. Casablanca also hosts the pr...Read more

Casablanca (Arabic: الدار البيضاء, romanized: ad-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, [adˈdaːru ɫbajdˤaːʔ], lit. 'White House') is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business center. Located on the Atlantic coast of the Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a population of about 3.71 million in the urban area, and over 4.27 million in Greater Casablanca, making it the most populous city in the Maghreb region, and the eighth-largest in the Arab world.

Casablanca is Morocco's chief port, with the Port of Casablanca being one of the largest artificial ports in Africa, and the third-largest port in North Africa, after Tanger-Med (40 km (25 mi) east of Tangier) and Port Said. Casablanca also hosts the primary naval base for the Royal Moroccan Navy.

Casablanca is a significant financial centre, ranking 54th globally in the September 2023 Global Financial Centres Index rankings, between Brussels and Rome. The Casablanca Stock Exchange is Africa's third-largest in terms of market capitalization, as of December 2022.

Major Moroccan companies and many of the largest American and European companies operating in the country have their headquarters and main industrial facilities in Casablanca. Recent industrial statistics show that Casablanca is the main industrial zone in the country.

The area that is today Casablanca was founded and settled by Berbers by the seventh century BC.[1] It was used as a port by the Phoenicians, then the Romans.[citation needed] In his book Description of Africa, Leo Africanus refers to ancient Casablanca as "Anfa", a great city founded in the Berber kingdom of Barghawata in 744 AD. He believed Anfa was the most "prosperous city on the Atlantic Coast because of its fertile land."[2] Barghawata rose as an independent state around this time, and continued until it was conquered by the Almoravids in 1068. After the defeat of the Barghawata in the 12th century, Arab tribes of Hilal and Sulaym descent settled in the region, mixing with the local Berbers, which led to widespread Arabization.[3][4] During the 14th century, under the Merinids, Anfa rose in importance as a port. The last of the Merinids were ousted by a popular revolt in 1465.[5]

Portuguese conquest and Spanish influence Casablanca in 1572, still called "Anfa" in this coloured engraving, although the Portuguese had already renamed it "Casa Branca" – "White House" – later Hispanicised to "Casablanca".

Casablanca in 1572, still called "Anfa" in this coloured engraving, although the Portuguese had already renamed it "Casa Branca" – "White House" – later Hispanicised to "Casablanca".In the early 15th century, the town became an independent state once again, and emerged as a safe harbour for pirates and privateers. The Portuguese consequently bombarded the town into ruins in 1468.[6] The town that grew up around it was called Casa Branca, meaning "white house" in Portuguese.

The town was finally rebuilt between 1756 and 1790 by Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah, the grandson of Moulay Ismail and an ally of George Washington, with the help of Spaniards from the nearby emporium. The town was called ad-Dār al-Bayḍāʼ (الدار البيضاء), the Arabic translation of the Portuguese Casa Branca.

Colonial struggleIn the 19th century, the area's population began to grow as it became a major supplier of wool to the booming textile industry in Britain and shipping traffic increased (the British, in return, began importing gunpowder tea, used in Morocco's national drink, mint tea).[7] By the 1860s, around 5,000 residents were there, and the population grew to around 10,000 by the late 1880s.[8] Casablanca remained a modestly sized port, with a population reaching around 12,000 within a few years of the French conquest and arrival of French colonialists in 1906. By 1921, this rose to 110,000,[9] largely through the development of shanty towns.

Bombardment of CasablancaThe Treaty of Algeciras of 1906 formalized French preeminence in Morocco and included three measures that directly impacted Casablanca: that French officers would control operations at the customs office and seize revenue as collateral for loans given by France, that the French holding company La Compagnie Marocaine would develop the port of Casablanca, and that a French-and-Spanish-trained police force would be assembled to patrol the port.[10]

To build the port's breakwater, narrow-gauge track was laid in June 1907 for a small Decauville locomotive to connect the port to a quarry in Roches Noires, passing through the sacred Sidi Belyout graveyard. In resistance to this and the measures of the 1906 Treaty of Algeciras, tribesmen of the Chaouia attacked the locomotive, killing 9 Compagnie Marocaine laborers—3 French, 3 Italians, and 3 Spanish.[11]

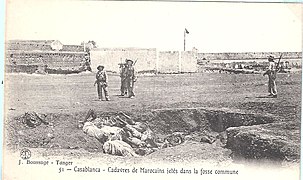

In response, the French bombarded the city in August 1907 with multiple gunboats and landed troops inside the town, causing severe damage and killing between 600 and 3,000 Moroccans.[12] Estimates for the total casualties are as high as 15,000 dead and wounded. In the immediate aftermath of the bombardment and the deployment of French troops, the European homes and the Mellah, or Jewish quarter, were sacked, and the latter was also set ablaze.[13]

As Oujda had already been occupied, the bombardment and military invasion of the city opened a western front to the French military conquest of Morocco.

![A man inspects the derailed Decauville locomotive at the scene of the attack that served as the pretext for the French bombardment of Casablanca in 1907.[14][15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Derailed_locomotive_in_Casablanca_1907.jpg/369px-Derailed_locomotive_in_Casablanca_1907.jpg)

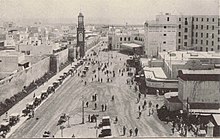

Place de France (now United Nations Square) in 1917.[16] With its landmark Clock Tower, this space became a contact point between what the colonists called the ville indigène to the left—comprising the Mellah and the Medina—and the European nouvelle ville to the right.

Place de France (now United Nations Square) in 1917.[16] With its landmark Clock Tower, this space became a contact point between what the colonists called the ville indigène to the left—comprising the Mellah and the Medina—and the European nouvelle ville to the right. Henri Prost's plans to extend 4éme Zouaves Street (now Félix Houphouët-Boigny Street) from the port to the Place de France (now United Nations Square), part of his redesigns of Casablanca's urban landscape.

Henri Prost's plans to extend 4éme Zouaves Street (now Félix Houphouët-Boigny Street) from the port to the Place de France (now United Nations Square), part of his redesigns of Casablanca's urban landscape.French control of Casablanca was formalized March 1912 when the Treaty of Fes established the French Protectorat.[17] Under French imperial control, Casablanca became a port of colonial extraction.[18]

General Hubert Lyautey assigned the planning of the new colonial port city to Henri Prost. As he did in other Moroccan cities, Prost designed a European ville nouvelle outside the walls of the medina. In Casablanca, he also designed a new "ville indigène" to house Moroccans arriving from other cities.[19]

Europeans formed almost half the population of Casablanca.[20]

A 1937-1938 typhoid fever outbreak was exploited by colonial authorities to justify the appropriation of urban spaces in Casablanca.[21][22] Moroccans residing in informal housing were cleared out of the center and displaced, notably to Carrières Centrales.[21]

World War IIAfter Philippe Pétain of France signed the armistice with the Nazis, he ordered French troops in France's colonial empire to defend French territory against any aggressors—Allied or otherwise—applying a policy of "asymmetrical neutrality" in favour of the Germans.[23] French colonists in Morocco generally supported Pétain, while Moroccans tended to favour de Gaulle and the Allies.[24]

Operation Torch, which started on 8 November 1942, was the British-American invasion of French North Africa during the North African campaign of World War II. The Western Task Force, composed of American units led by Major General George S. Patton and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, carried out the invasions of Mehdia, Fedhala, and Asfi. American forces captured Casablanca from Vichy control when France surrendered 11 November 1942, but the Naval Battle of Casablanca continued until American forces sank German submarine U-173 on 16 November.[25]

Casablanca was the site of the Nouasseur Air Base, a large American air base used as the staging area for all American aircraft for the European Theatre of Operations during World War II. The airfield has since become Mohammed V International Airport.

Anfa ConferenceCasablanca hosted the Anfa Conference (also called the Casablanca Conference) in January 1943. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt discussed the progress of the war. Also in attendance were the Free France generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud, though they played minor roles and didn't participate in the military planning.

It was at this conference that the Allies adopted the doctrine of "unconditional surrender," meaning that the Axis powers would be fought until their defeat. Roosevelt also met privately with Sultan Muhammad V and expressed his support for Moroccan independence after the war.[26] This became a turning point, as Moroccan nationalists were emboldened to openly seek complete independence.[26]

Toward independenceDuring the 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was a major centre of anti-French rioting.

On 7 April 1947, a massacre of working class Moroccans, carried out by Senegalese Tirailleurs in the service of the French colonial army, was instigated just as Sultan Muhammed V was due to make a speech in Tangier appealing for independence.[27]

Riots in Casablanca took place from 7–8 December 1952, in response to the assassination of the Tunisian labor unionist Farhat Hached by La Main Rouge—the clandestine militant wing of French intelligence.[28] Then, on 25 December 1953 (Christmas Day), Muhammad Zarqtuni orchestrated a bombing of Casablanca's Central Market in response to the forced exile of Sultan Muhammad V and the royal family on 20 August (Eid al-Adha) of that year.[29]

Since independenceMorocco gained independence from France in 1956. The post-independence era witnessed significant urban transformations and socio-economic shifts, particularly in neighborhoods like Hay Mohammadi, which were deeply impacted by neoliberal policies and state-led urban redevelopment projects.[30]

Casablanca GroupOn 4–7 January 1961, the city hosted an ensemble of progressive African leaders during the Casablanca Conference of 1961. Among those received by King Muhammad V were Gamal Abd An-Nasser, Kwame Nkrumah, Modibo Keïta, and Ahmed Sékou Touré, Ferhat Abbas.[15][31][32]

Jewish emigrationCasablanca was a major departure point for Jews leaving Morocco through Operation Yachin, an operation conducted by Mossad to secretly migrate Moroccan Jews to Israel between November 1961 and spring 1964.[33]

1965 riotsThe 1965 student protests organized by the National Union of Popular Forces-affiliated National Union of Moroccan Students, which spread to cities around the country and devolved into riots, started on 22 March 1965, in front of Lycée Mohammed V in Casablanca.[34][35][36] The protests started as a peaceful march to demand the right to public higher education for Morocco, but expanded to include concerns of labourers, the unemployed, and other marginalized segments of society, and devolved into vandalism and rioting.[37] The riots were violently repressed by security forces with tanks and armoured vehicles; Moroccan authorities reported a dozen deaths while the UNFP reported more than 1,000.[34]

King Hassan II blamed the events on teachers and parents, and declared in a speech to the nation on 30 March 1965: "There is no greater danger to the State than a so-called intellectual. It would have been better if you were all illiterate."[38][39]

1981 riotsOn 6 June 1981, the Casablanca Bread Riots took place,[40] which were sparked by a sharp increase in the price of necessities such as butter, sugar, wheat flour, and cooking oil following a period of severe drought.[41] Hassan II appointed the French-trained interior minister Driss Basri as hardliner, who would later become a symbol of the Years of Lead, with quelling the protests.[42] The government stated that 66 people were killed and 100 were injured, while opposition leaders put the number of dead at 637, saying that many of these were killed by police and army gunfire.[40]

MudawanaIn March 2000, more than 60 women's groups organized demonstrations in Casablanca proposing reforms to the legal status of women in the country.[43] About 40,000 women attended, calling for a ban on polygamy and the introduction of divorce law (divorce being a purely religious procedure at that time). Although the counter-demonstration attracted half a million participants, the movement for change started in 2000 was influential on King Mohammed VI, and he enacted a new mudawana, or family law, in early 2004, meeting some of the demands of women's rights activists.[44]

Further historyOn 16 May 2003, 33 civilians were killed and more than 100 people were injured when Casablanca was hit by a multiple suicide bomb attack carried out by Moroccans and claimed by some to have been linked to al-Qaeda. Twelve suicide bombers struck five locations in the city.[45]

Another series of suicide bombings struck the city in early 2007.[46][47][48] These events illustrated some of the persistent challenges the city faces in addressing poverty and integrating disadvantaged neighborhoods and populations.[49] One initiative to improve conditions in the city's disadvantaged neighborhoods was the creation of the Sidi Moumen Cultural Center.[49]

As calls for reform spread through the Arab world in 2011, Moroccans joined in, but concessions by the ruler led to acceptance.[citation needed] However, in December, thousands of people demonstrated in several parts of the city[citation needed], especially the city center near la Fontaine, desiring more significant political reforms. On 1 November 2023, Casablanca along with Ouarzazate joined UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network.[50][51]

Add new comment