Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christian structures in England and forms part of a World Heritage Site. Its formal title is the Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Christ, Canterbury.

Founded in 597, the cathedral was completely rebuilt between 1070 and 1077. The east end was greatly enlarged at the beginning of the 12th century, and largely rebuilt in the Gothic style following a fire in 1174, with significant eastward extensions to accommodate the flow of pilgrims visiting the shrine of Thomas Becket, the archbishop who was murdered in the cathedral in 1170. The Norman nave and transepts survived until the late 14th century, when they were demolished to make way for the present structures.

Before the English Reformation, the cathedral was...Read more

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christian structures in England and forms part of a World Heritage Site. Its formal title is the Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Christ, Canterbury.

Founded in 597, the cathedral was completely rebuilt between 1070 and 1077. The east end was greatly enlarged at the beginning of the 12th century, and largely rebuilt in the Gothic style following a fire in 1174, with significant eastward extensions to accommodate the flow of pilgrims visiting the shrine of Thomas Becket, the archbishop who was murdered in the cathedral in 1170. The Norman nave and transepts survived until the late 14th century, when they were demolished to make way for the present structures.

Before the English Reformation, the cathedral was part of a Benedictine monastic community known as Christ Church, Canterbury, as well as being the seat of the archbishop.

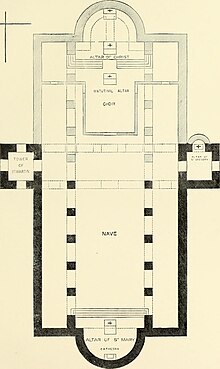

Plan of Canterbury Cathedral before the 1067 fireRoman

Plan of Canterbury Cathedral before the 1067 fireRoman

Christianity in Britain is referred to by Tertullian as early as 208 AD[1] and Origen mentions it in 238 AD. In 314 three Bishops from Britain attended the Council of Arles.[2] Following the end of Roman life in Britain, during the first three decades of the fifth century,[3] and the subsequent arrival of the non-Christian Anglo-Saxons, Christian life in the east of the island was disrupted.[4] Textual sources however suggest that the Christian communities established in the Roman province survived in Western Britain during the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries.[5] This Western British Christianity proceeded to develop on its own terms.[6]

In 596, Pope Gregory I ordered that Augustine of Canterbury, previously the abbot of St Andrew's Benedictine Abbey in Rome, lead the Gregorian Mission to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity.[7] According to the writings of the later monk Bede, these Augustinian missionaries gained permission from the Kentish king to restore several pre-existing churches.[8] Augustine then founded Canterbury cathedral in 597 and dedicated it to Jesus Christ, the Holy Saviour.[9] When other dioceses were founded in England Augustine was made archbishop.

Augustine also founded the Abbey of St Peter and Paul outside the Canterbury city walls. This was later rededicated to St Augustine himself and was for many centuries the burial place of the successive archbishops. The abbey is part of the World Heritage Site of Canterbury, along with the cathedral and the ancient Church of St Martin.[10]

Early MedievalBede recorded that Augustine reused a former Roman church. The oldest remains found during excavations beneath the present nave in 1993 were, however, parts of the foundations of an Anglo-Saxon building, which had been constructed across a Roman road.[11][12] They indicate that the original church consisted of a nave, possibly with a narthex, and side-chapels to the north and south. A smaller subsidiary building was found to the south-west of these foundations.[12] During the 9th or 10th century this church was replaced by a larger structure (161 by 75 ft, 49 by 23 m) with a squared west end. It appears to have had a square central tower.[12] The 11th-century chronicler Eadmer, who had known the Saxon cathedral as a boy, wrote that, in its arrangement, it resembled St Peter's in Rome, indicating that it was of basilican form, with an eastern apse.[13]

During the reforms of Dunstan, archbishop from 960 until his death in 988,[14] a Benedictine abbey named Christ Church Priory was added to the cathedral. But the formal establishment as a monastery seems to date only to c. 997 and the community only became fully monastic from Lanfranc's time onwards (with monastic constitutions addressed by him to Prior Henry). Dunstan was buried on the south side of the high altar.

Anglo-Saxon King Æthelred the Unready and Norman-born Emma of Normandy were married at Canterbury Cathedral in the Spring of 1002, and Emma was consecrated "Queen Ælfgifu".[15][16]

The cathedral was badly damaged during Danish raids on Canterbury in 1011. The archbishop, Ælfheah, was taken hostage by the raiders and eventually killed at Greenwich on 19 April 1012, the first of Canterbury's five martyred archbishops.[a] After this a western apse was added as an oratory of Saint Mary, probably during the archbishopric of Lyfing (1013–1020) or Aethelnoth (1020–1038).

The 1993 excavations revealed that the new western apse was polygonal, and flanked by hexagonal towers, forming a westwork. It housed the archbishop's throne, with the altar of St Mary just to the east. At about the same time that the westwork was built, the arcade walls were strengthened and towers added to the eastern corners of the church.[12]

NormanThe cathedral was destroyed by fire in 1067, a year after the Norman Conquest. Rebuilding began in 1070 under the first Norman archbishop, Lanfranc (1070–1077). He cleared the ruins and reconstructed the cathedral to a design based closely on that of the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Caen, where he had previously been abbot, using stone brought from France.[18] The new church, its central axis about 5 m south of that of its predecessor,[12] was a cruciform building, with an aisled nave of nine bays, a pair of towers at the west end, aisleless transepts with apsidal chapels, a low crossing tower, and a short quire ending in three apses. It was dedicated in 1077.[19]

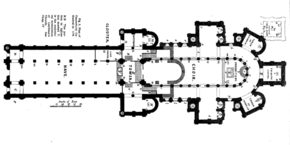

The Norman cathedral, after its expansion by Ernulf and Conrad.

The Norman cathedral, after its expansion by Ernulf and Conrad.Under Lanfranc's successor Anselm, who was twice exiled from England, the responsibility for the rebuilding or improvement of the cathedral's fabric was largely left in the hands of the priors.[20] Following the election of Prior Ernulf in 1096, Lanfranc's inadequate east end was demolished, and replaced with an eastern arm 198 feet long, doubling the length of the cathedral. It was raised above a large and elaborately decorated crypt. Ernulf was succeeded in 1107 by Conrad, who completed the work by 1126.[21] The new quire took the form of a complete church in itself, with its own transepts; the east end was semicircular in plan, with three chapels opening off an ambulatory.[21] A free-standing campanile was built on a mound in the cathedral precinct in about 1160.[22]

As with many Gothic church buildings, the interior of the quire was richly embellished.[23] William of Malmesbury wrote: "Nothing like it could be seen in England either for the light of its glass windows, the gleaming of its marble pavements, or the many-coloured paintings which led the eyes to the paneled ceiling above."[23]

Though named after the 6th-century founding archbishop, the Chair of St Augustine, the ceremonial enthronement chair of the Archbishop of Canterbury, may date from the Norman period. Its first recorded use is in 1205.

Plantagenet period Martyrdom of Thomas Becket Image of Thomas Becket from a stained glass window

Image of Thomas Becket from a stained glass window The 12th-century quire

The 12th-century quireA pivotal moment in the history of the cathedral was the murder of the archbishop, Thomas Becket, in the north-west transept (also known as the Martyrdom) on Tuesday 29 December 1170, by knights of King Henry II. The king had frequent conflicts with the strong-willed Becket and is said to have exclaimed in frustration, "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" Four knights took it literally and murdered Becket in his own cathedral. After the Anglo-Saxon Ælfheah in 1012, Becket was the second Archbishop of Canterbury to be murdered.

The posthumous veneration of Becket transformed the cathedral into a place of pilgrimage, necessitating both expansion of the building and an increase in wealth, via revenues from pilgrims, in order to make expansion possible.

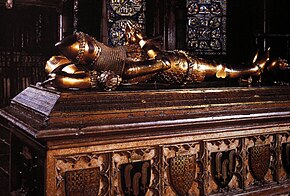

Rebuilding of the quire Tomb of Edward, the Black Prince

Tomb of Edward, the Black PrinceIn September 1174 the quire was severely damaged by fire, necessitating a major reconstruction,[24] the progress of which was recorded in detail by a monk named Gervase.[25] The crypt survived the fire intact,[26] and it was found possible to retain the outer walls of the quire, which were increased in height by 12 feet (3.7 m) in the course of the rebuilding, but with the round-headed form of their windows left unchanged.[27] Everything else was replaced in the new Gothic style, with pointed arches, rib vaulting, and flying buttresses. The limestone used was imported from Caen in Normandy, and Purbeck marble was used for the shafting. The quire was back in use by 1180 and in that year the remains of Dunstan and Ælfheah were moved there from the crypt.[28]

The master-mason appointed to rebuild the quire was a Frenchman, William of Sens. Following his injury in a fall from the scaffolding in 1179 he was replaced by one of his former assistants, known as William the Englishman.[28]

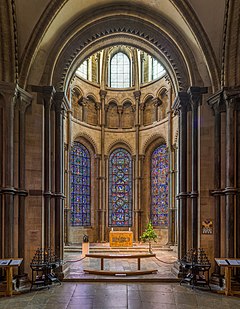

Trinity Chapel and Shrine of Thomas Becket Stained glass in the Trinity Chapel

Stained glass in the Trinity Chapel ’Becket's crown’ chapel at the far east end of the cathedral

’Becket's crown’ chapel at the far east end of the cathedralIn 1180–1184, in place of the old, square-ended, eastern chapel, the present Trinity Chapel was constructed, a broad extension with an ambulatory, designed to house the shrine of St Thomas Becket.[28] A further chapel, circular in plan, was added beyond that, which housed further relics of Becket,[28] widely believed to have included the top of his skull, struck off in the course of his assassination. This latter chapel became known as the "Corona" or "Becket's Crown".[29] These new parts east of the quire transepts were raised on a higher crypt than Ernulf's quire, necessitating flights of steps between the two levels. Work on the chapel was completed in 1184,[28] but Becket's remains were not moved from his tomb in the crypt until 1220.[30] Further significant interments in the Trinity Chapel included those of Edward Plantagenet (The "Black Prince") and King Henry IV.

The shrine in the Trinity Chapel was placed directly above Becket's original tomb in the crypt. A marble plinth, raised on columns, supported what an early visitor, Walter of Coventry, described as "a coffin wonderfully wrought of gold and silver, and marvellously adorned with precious gems".[31] Other accounts make clear that the gold was laid over a wooden chest, which in turn contained an iron-bound box holding Becket's remains.[32] Further votive treasures were added to the adornments of the chest over the years, while others were placed on pedestals or beams nearby, or attached to hanging drapery.[33] For much of the time, the chest (or "feretory") was kept concealed by a wooden cover, which would be theatrically raised by ropes once a crowd of pilgrims had gathered.[30][32] The Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who visited in 1512–1514, recorded that, once the cover was raised, "the Prior ... pointed out each jewel, telling its name in French, its value, and the name of its donor; for the principal of them were offerings sent by sovereign princes."[34]

The income from pilgrims (such as those portrayed in Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales) who visited Becket's shrine, which was regarded as a place of healing, largely paid for the subsequent rebuilding of the cathedral and its associated buildings. This revenue included the profits from the sale of pilgrim badges depicting Becket, his martyrdom, or his shrine.

The shrine was removed in 1538. King Henry VIII allegedly summoned the dead saint to court to face charges of treason. Having failed to appear, he was found guilty in his absence and the treasures of his shrine were confiscated, carried away in two coffers and 26 carts.[35]

Monastic buildings Cloisters

Cloisters The waterworks plan traced from the original by Robert Willis (1868)[36]

The waterworks plan traced from the original by Robert Willis (1868)[36]A bird's-eye view of the cathedral and its monastic buildings, made in about 1165[37] and known as the "waterworks plan" is preserved in the Eadwine Psalter in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.[38] A detailed description of the plan can be found in the classic paper by Willis.[36]: 158–181 [39] It shows that Canterbury employed the same general principles of arrangement common to all Benedictine monasteries, although, unusually, the cloister and monastic buildings were to the north, rather than the south of the church. There was a separate chapter-house[37] which still exists, said to be "the largest of its kind in all of England". Stained glass here depicts the history of Canterbury.[40]

The stained glass windows in the chapter-house

The stained glass windows in the chapter-houseThe buildings formed separate groups around the church. Adjoining it, on the north side, stood the cloister and the buildings devoted to the monastic life. To the east and west of these were those devoted to the exercise of hospitality. Also to the east was the infirmary, with its own chapel. To the north, a large open court divided the monastic buildings from menial ones, such as the stables, granaries, barn, bakehouse, brewhouse, and laundries, inhabited by the lay servants of the establishment. At the greatest possible distance from the church, beyond the precinct of the monastery, was the eleemosynary department. The almonry for the relief of the poor, with a great hall annexed, formed the paupers' hospitium.[37]

The group of buildings devoted to monastic life included two cloisters. The great cloister was surrounded by the buildings essentially connected with the daily life of the monks: the church to the south, with the refectory placed as always on the side opposite, the dormitory, raised on a vaulted undercroft, and the chapter-house adjacent, and the lodgings of the cellarer, responsible for providing both monks and guests with food, to the west. A passage under the dormitory led eastwards to the smaller or infirmary cloister, appropriated to sick and infirm monks.[37]

Infirmary Chapel ruins

Infirmary Chapel ruinsThe hall and chapel of the infirmary extended east of this cloister, resembling in form and arrangement the nave and chancel of an aisled church. Beneath the dormitory, overlooking the green court or herbarium, lay the "pisalis" or "calefactory", the common room of the monks. At its northeast corner access was given from the dormitory to the necessarium, a building in the form of a Norman hall, 145 feet (44 m) long by 25 feet (7.6 m) broad, containing 55 seats. It was constructed with careful regard to hygiene, with a stream of water running through it from end to end.[37]

The circular lavatorium tower, for washing hands

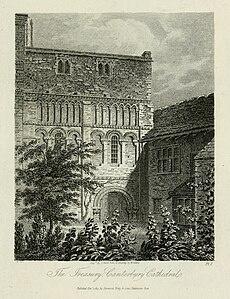

The circular lavatorium tower, for washing hands View of the treasury in about 1814

View of the treasury in about 1814A second smaller dormitory for the conventual officers ran from east to west. Close to the refectory, but outside the cloisters, were the domestic offices connected with it: to the north, the kitchen, 47 feet (14 m) square, with a pyramidal roof, and the kitchen court; to the west, the butteries, pantries, etc. The infirmary had a small kitchen of its own. Opposite the refectory door in the cloister were two buildings where the monks washed before and after eating.[37] One of these is the circular two-storey lavatorium tower.[36]: 62–63 To the south of the infirmary cloister, close to the east end of the cathedral, is the treasury, with a distinctive octapartite vault.[39]: 56

The buildings devoted to hospitality were divided into three groups. The prior's group were "entered at the south-east angle of the green court, placed near the most sacred part of the cathedral, as befitting the distinguished ecclesiastics or nobility who were assigned to him." The cellarer's buildings, where middle-class visitors were entertained, stood near the west end of the nave. The inferior pilgrims and paupers were relegated to the north hall or almonry, just within the gate.[37]

Priors of Christ Church Priory included John of Sittingbourne (elected 1222, previously a monk of the priory) and William Chillenden, (elected 1264, previously monk and treasurer of the priory).[41] The monastery was granted the right to elect their own prior if the seat was vacant by the pope, and – from Gregory IX onwards – the right to a free election (though with the archbishop overseeing their choice). Monks of the priory have included Æthelric I, Æthelric II, Walter d'Eynsham, Reginald fitz Jocelin (admitted as a confrater shortly before his death), Nigel de Longchamps and Ernulf. The monks often put forward candidates for Archbishop of Canterbury, either from among their number or outside, since the archbishop was nominally their abbot, but this could lead to clashes with the king or pope should they put forward a different man – examples are the elections of Baldwin of Forde and Thomas Cobham.

Quire screen[42]14th and 15th centuries

Quire screen[42]14th and 15th centuries

Early in the 14th century, Prior Eastry erected a stone quire screen and rebuilt the chapter house, and his successor, Prior Oxenden inserted a large five-light window into St Anselm's chapel.[43]

The cathedral was seriously damaged by the 1382 Dover Straits earthquake, losing its bells and campanile.[44]

Plan of Canterbury Cathedral showing the complex ribbing of the Perpendicular vaulting in the nave and transepts

Plan of Canterbury Cathedral showing the complex ribbing of the Perpendicular vaulting in the nave and transepts View from the northwest circa 1890–1900.

View from the northwest circa 1890–1900.From the late 14th century the nave and transepts were rebuilt, on the Norman foundations in the Perpendicular style under the direction of the noted master mason Henry Yevele.[45] In contrast to the contemporary rebuilding of the nave at Winchester, where much of the existing fabric was retained and remodelled, the piers were entirely removed, and replaced with less bulky Gothic ones, and the old aisle walls were completely taken down except for a low "plinth" left on the south side.[46][12] More Norman fabric was retained in the transepts, especially in the east walls,[46] and the old apsidal chapels were not replaced until the mid-15th century.[43] The arches of the new nave arcade were exceptionally high in proportion to the clerestory.[43] The new transepts, aisles, and nave were roofed with lierne vaults, enriched with bosses. Most of the work was done during the priorate of Thomas Chillenden (1391–1411): Chillenden also built a new quire screen at the east end of the nave, into which Eastry's existing screen was incorporated.[43] The Norman stone floor of the nave, however, survived until its replacement in 1786.[12]

The Perpendicular nave

The Perpendicular nave Canterbury Cathedral, fan vaulting of the crossing inside the central Bell Harry Tower

Canterbury Cathedral, fan vaulting of the crossing inside the central Bell Harry TowerFrom 1396 the cloisters were repaired and remodelled by Yevele's pupil Stephen Lote who added the lierne vaulting. It was during this period that the wagon-vaulting of the chapter house was created.

A shortage of money and the priority given to the rebuilding of the cloisters and chapterhouse meant that the rebuilding of the west towers was neglected. The south-west tower was not replaced until 1458, and the Norman north-west tower survived until 1834 when it was replaced by a replica of its Perpendicular companion.[43]

In about 1430 the south transept apse was removed to make way for a chapel, founded by Lady Margaret Holland and dedicated to St Michael and All Angels. The north transept apse was replaced by a Lady Chapel, built-in 1448–1455.[43]

The 235-foot (72 m) crossing tower was begun in 1433, although preparations had already been made during Chillenden's priorate when the piers had been reinforced. Further strengthening was found necessary around the beginning of the 16th century when buttressing arches were added under the southern and western tower arches. The tower is often known as the "Angel Steeple", after a gilded angel that once stood on one of its pinnacles.[43]

Modern period The decorative font in the naveThe Reformation, Dissolution and Puritanism

The decorative font in the naveThe Reformation, Dissolution and Puritanism

The cathedral ceased to be an abbey during the Dissolution of the Monasteries when all religious houses were suppressed. Canterbury surrendered in March 1539, and reverted to its previous status of 'a college of secular canons'. According to the cathedral's own website, it had been a Benedictine monastery since the 900s. The New Foundation came into being on 8 April 1541.[47] The shrine to St Thomas Becket was destroyed on the orders of Henry VIII and the relics lost.

In around 1576, the crypt of the cathedral was granted to the Huguenot congregation of Canterbury to be used as their Church of the Crypt.

In 1642–1643, during the English Civil War, Puritan iconoclasts led by Edwin Sandys (Parliamentarian) caused significant damage during their "cleansing" of the cathedral.[48] Included in that campaign was the destruction of the statue of Christ in the Christ Church Gate and the demolition of the wooden gates by a group led by Richard Culmer.[49] The statue would not be replaced until 1990 but the gates were restored in 1660 and a great deal of other repair work started at that time; that would continue until 1704.[50][51]

FurnishingsIn 1688, the joiner Roger Davis, citizen of London, removed the 13th-century misericords and replaced them with two rows of his own work on each side of the quire. Some of Davis's misericords have a distinctly medieval flavour and he may have copied some of the original designs. When Sir George Gilbert Scott carried out renovations in the 19th century, he replaced the front row of Davis' misericords, with new ones of his own design, which seem to include many copies of those at Gloucester Cathedral, Worcester Cathedral and New College, Oxford.

The west front in 1821 showing the Norman northwest tower at left prior to rebuilding (coloured engraving)Statues on the West Front

The west front in 1821 showing the Norman northwest tower at left prior to rebuilding (coloured engraving)Statues on the West Front

Most of the statues that currently adorn the west front of the cathedral were installed in the 1860s when the South Porch was being renovated. At that time, the niches were vacant and the Dean of the cathedral thought that the appearance of the cathedral would be improved if they were filled. The Victorian sculptor Theodore Pfyffers was commissioned to create the statues and most of them were installed by the end of the 1860s. There are currently 53 statues representing various figures who have been influential in the life of the cathedral and the English church such as clergy, members of the royal family, saints, and theologians. Archbishops of Canterbury from Augustine of Canterbury and Lanfranc, to Thomas Cranmer and William Laud are represented. Kings and Queens from Æthelberht and Bertha of Kent, to Victoria and Elizabeth II are included.[52]

18th century to the present The Christchurch Gate with the new (1990) bronze statue of Christ; the original was destroyed in 1643

The Christchurch Gate with the new (1990) bronze statue of Christ; the original was destroyed in 1643The original towers of Christ Church Gate were removed in 1803 and were replaced in 1937. The statue of Christ was replaced in 1990 with a bronze sculpture of Christ by Klaus Ringwald.[50]

The original Norman northwest tower, which had a lead spire until 1705,[53] was demolished in 1834 owing to structural concerns.[43] It was replaced with a Perpendicular-style twin of the southwest tower (designed by Thomas Mapilton), now known as the Arundel Tower, providing a more symmetrical appearance for the cathedral.[54][51] This was the last major structural alteration to the cathedral to be made.

In 1866, there were six residentiary canonries, of which one was annexed to the Archdeaconry of Canterbury and another to that of Maidstone.[55] In September 1872, a large portion of the Trinity Chapel roof was completely destroyed by fire. There was no significant damage to the stonework or interior and the damage was quickly repaired.[56]

The cathedral did not sustain serious damage during either World War

The cathedral did not sustain serious damage during either World WarDuring the bombing raids of the Second World War its library was destroyed,[57] but the cathedral did not sustain extensive bomb damage; the local Fire Wardens doused any flames on the wooden roof.[58]

In 1986, a new Martyrdom Altar was installed in the northwest transept, on the spot where Thomas Becket was slain, the first new altar in the cathedral for 448 years. Mounted on the wall above it, there is a metal sculpture by Truro sculptor Giles Blomfield depicting a cross flanked by two bloodstained swords which, together with the shadows they cast, represent the four knights who killed Becket. A stone plaque also commemorates Pope John Paul II's visit to the United Kingdom in 1982.[59] Antony Gormley's sculpture Transport was unveiled in the crypt in 2011. It is made from iron nails from the roof of the south-east transept.[60]

In 2015, Sarah Mullally and Rachel Treweek became the first women to be ordained as bishops in the cathedral, as Bishop of Crediton and Bishop of Gloucester respectively.[61] In 2022, it was announced that David Monteith, who is openly gay and in a civil partnership, would serve as Dean of the Cathedral.[62][63]

The cathedral is Regimental Church of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment and a graduation venue for the University of Kent[64] and Canterbury Christ Church University.[65]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment