The Villa Romana del Casale (Sicilian: Villa Rumana dû Casali) is a large and elaborate Roman villa or palace located about 3 km from the town of Piazza Armerina, Sicily. Excavations have revealed Roman mosaics which, according to the Grove Dictionary of Art, are the richest, largest and most varied collection that remains, for which the site has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The villa and artwork contained within date to the early 4th century AD.

The mosaic and opus sectile floors cover some 3,500 m2 and are almost unique in their excellent state of preservation due to the landslide and floods that covered the remains.

Although less well-known, an extraordinary collection of frescoes covered not only the interior rooms, but also the exterior walls.

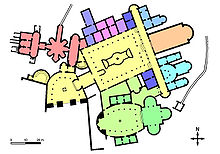

Plan of the villa

Plan of the villa Peristyle

PeristyleThe visible remains of the villa were constructed in the first quarter of the 4th century AD on the remains of an older villa rustica and are the pars dominica, or master's residence, of a large latifundium or agricultural estate.[1]

The nearby settlement of Philosophiana was probably the centre of production and commercial activities, as well as a rest stop along the Catania-Agrigento road, as mentioned in the Itinerarium Antonini as a mansio or statio, for travellers looking for a shelter for the night and a change of horses. The latifundium extended to the mouth of the Gela river identifiable by the many brick stamps with inscriptions PHIL SOPH.[2]

During the first two centuries of the Empire, Sicily had gone through an economic depression due to the production system of large estates based on slave labour: urban life had suffered a decline, the countryside was deserted and the rich owners did not reside there, as the lack of suitable villas would seem to indicate. Furthermore, the Roman government neglected the territory, which became a place of exile and a refuge for slaves and brigands. At the beginning of the 4th century rural Sicily entered a new period of prosperity with commercial settlements and agricultural villages that seem to reach the apex of their expansion and activity. New constructions are seen in the localities of Philosophiana, Sciacca, Kaukana (Punta Secca), Naxos and elsewhere. An obvious sign of transformation was the new title assigned to the governor of the island, from corrector to consularis.

The reasons seem to be twofold. Firstly, the renewed importance of the provinces of proconsular Africa and Tripolitania for grain supplies to Italy, when Egyptian production, which had up to then satisfied the needs of Rome, was sent to Constantinople, the new imperial capital from 330. Sicily consequently assumed a central role on the new trade routes from Africa. Secondly, the more affluent classes, of equestrian and senatorial rank, began to abandon urban life by retreating to their possessions in the countryside, due to the growing tax burden and the expenses they had to pay for cities. The owners also looked after their own lands, which were no longer cultivated by slaves, but by colonists. Considerable sums of money were spent on enlarging, beautifying and making the villas more comfortable (e.g. Villa Romana del Tellaro).

The owner's identity has long been discussed and many different hypotheses have been formulated. Some features such as the Tetrarchic military insignia and the probable Tetrarchic date of the mosaics have led scholars to suggest an imperial owner such as Maximian. Other scholars believe that the villa was the centre of the great estate of a high-level senatorial aristocrat.[3]

Three successive construction phases have been identified; the first phase involved the quadrangular peristyle and the facing rooms. The private bath complex was then added on a north-west axis. In a third phase the villa took on a public character: the baths were given a new entrance and a large latrine. A grand monumental entrance was built, off-axis to the peristyle but aligned with the new baths' entrance in a formal arrangement with the elliptical (or ovoid) arcade and the grand tri-apsidal hall. This hall was used for entertainment and relaxation for special guests and replaced the two state halls of the peristyle (the “hall of the small hunt” and the “diaeta of Orpheus”). The basilica was expanded and decorated with beautiful and exotic marbles.

The complex remained inhabited for at least 150 years. A village grew around it, named Platia (derived from the word palatium (palace).

Hunters in the Great Hunt mosaic

Hunters in the Great Hunt mosaicIn the 5th and 6th centuries, the villa was fortified for defensive purposes by thickening the perimeter walls and closing of the arcades of the aqueduct to the baths. The villa was damaged and perhaps destroyed during the short domination of the Vandals between 469–78. The outbuildings remained in use, at least in part, during the Byzantine and Arab periods. The settlement was destroyed in 1160–1 during the reign of William I. The site was abandoned in the 12th century after a landslide covered the villa. Survivors moved to the current location of Piazza Armerina.

The villa was almost entirely forgotten, although some of the tallest parts of the remains were always visible above ground. The area was cultivated for crops. Early in the 19th century, pieces of mosaics and some columns were found. The first official archaeological excavations were carried out later in that century.[4]

The first professional excavations were made by Paolo Orsi in 1929, followed by the work of Giuseppe Cultrera in 1935–39. Major excavations took place in the period 1950–60 led by Gino Vinicio Gentili, after which a protective cover was built over the mosaics. In the 1970s Andrea Carandini carried out excavations at the site. Work has continued to the present day by the University of Rome, La Sapienza. In 2004 a large mediaeval settlement of the 10–12th centuries was found. Since then further sumptuous rooms of the villa have also been revealed.

Add new comment