The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his Academical Village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The original governing Board of Visitors included three U.S. presidents: Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, the latter as sitting president of the United States at the time of its foundation. As its first two rectors, Presidents Jefferson and Madison played key roles in the university's foundation, with Jefferson designing both the original courses of study and the university's architecture. Located within its historic 1,135-acre central campus, the university is composed of eight undergraduate and three professional schools: the School of Law, the Darden School of Business, and the School of Medicine.

The University of Virginia's scholars have played a major role in the developme...Read more

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his Academical Village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The original governing Board of Visitors included three U.S. presidents: Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, the latter as sitting president of the United States at the time of its foundation. As its first two rectors, Presidents Jefferson and Madison played key roles in the university's foundation, with Jefferson designing both the original courses of study and the university's architecture. Located within its historic 1,135-acre central campus, the university is composed of eight undergraduate and three professional schools: the School of Law, the Darden School of Business, and the School of Medicine.

The University of Virginia's scholars have played a major role in the development of many academic disciplines, including economics, law, literary art, visual art, and the sciences. The university is referred to as a "Public Ivy" for offering an academic experience similar to that of an Ivy League university. Admission to the university's graduate schools is selective, and the university is known in part for its historic foundations, student-run honor code, and secret societies.

In research, the university has been a member of the Association of American Universities for 120 years, and the journal Science credited its faculty with two of the top ten global scientific breakthroughs in a single year. In sports, the university athletic teams are called the Cavaliers and lead the Atlantic Coast Conference in team NCAA Championships for men's sports, also ranking second in women's and overall titles. In 2015, and again in 2019, the University of Virginia was presented with the Capital One Cup for fielding the nation's best overall athletics programs for men's sports.

The university's alumni, faculty, and researchers have included several U.S. presidents, heads of state, Nobel laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Fulbright Scholars. Some 30 different governors of U.S. states have attended the university, as have numerous U.S. senators and members of Congress. UVA has produced 56 Rhodes Scholars, eighth most in the United States, while its alumni have founded companies such as Reddit, CNET, VMware, and Space Adventures.

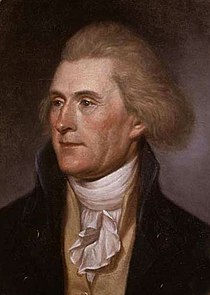

Thomas Jefferson, the university's founder, by Charles Willson Peale (1791)

Thomas Jefferson, the university's founder, by Charles Willson Peale (1791) The Rotunda, as pictured from the South Lawn

The Rotunda, as pictured from the South LawnIn 1802, while serving as president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson wrote to artist Charles Willson Peale that his concept of the new university would be "on the most extensive and liberal scale that our circumstances would call for and our faculties meet," and it might even attract talented students from "other states to come, and drink of the cup of knowledge."[1] Virginia was already home to the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, but Jefferson lost all confidence in his alma mater, partly because of its religious nature—it required all its students to recite a catechism—and its stifling of the sciences.[2][3] Jefferson had flourished under William & Mary professors William Small and George Wythe decades earlier, but the college was in a period of great decline and his concern became so dire by 1800 that he expressed to British chemist Joseph Priestley, "we have in that State, a college just well enough endowed to draw out the miserable existence to which a miserable constitution has doomed it." These words would ring true some seventy years later when William & Mary fell bankrupt after the Civil War and the Williamsburg college was shuttered completely in 1881, later being revived as primarily a small college for teachers until it regained university status later in the twentieth century.[4] Jefferson envisioned his new university would "be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it."[5]

In 1817, three presidents (Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison) and Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court John Marshall joined 24 other dignitaries at a meeting held in the Mountain Top Tavern at Rockfish Gap. After some deliberation, they selected nearby Charlottesville as the site of the new University of Virginia.[6] The UVA Board of Visitors purchased just outside Charlottesville a farm that had once been owned by James Monroe.[7] The Commonwealth of Virginia chartered a new flagship university to be based on the site in Charlottesville on January 25, 1819.

John Hartwell Cocke collaborated with James Madison, Monroe, and Joseph Carrington Cabell to fulfill Jefferson's dream to establish the university. Cocke and Jefferson were appointed to the building committee to supervise the construction.[8] The UVA Office of Equal Opportunity and Civil Rights is continuing to "seek opportunities to engage and acknowledge with respect that we live, learn, and work on [what once was] the territory of the Monacan Indian Nation."[9] Like many of its peers,[10] the university owned slaves who helped build the campus.[11] They also served students and professors.[11] The university's first classes met on March 7, 1825.[12]

In contrast to other universities of the day, at which one could study in either medicine, law, or divinity, the first students at the University of Virginia could study in one or several of eight independent schools – medicine, law, mathematics, chemistry, ancient languages, modern languages, natural philosophy, and moral philosophy.[13] Another innovation of the new university was that higher education would be separated from religious doctrine. UVA had no divinity school, was established independently of any religious sect, and the Grounds were planned and centered upon a library, the Rotunda, rather than a church, distinguishing it from peer universities still primarily functioning as seminaries for one particular strain of Protestantism or another.[14] Jefferson opined to philosopher Thomas Cooper that "a professorship of theology should have no place in our institution",[15] and never has there been one. There were initially two degrees awarded by the university: Graduate, to a student who had completed the courses of one school; and Doctor to a graduate in more than one school who had shown research prowess.[16]

James Madison was the second rector of the University of Virginia until 1836.

James Madison was the second rector of the University of Virginia until 1836.Jefferson was intimately involved in the university to the end, hosting Sunday dinners at his Monticello home for faculty and students. Jefferson viewed the university's foundation as having such great importance and potential that he counted it among his greatest accomplishments and insisted his grave mention only his status as author of the Declaration of Independence and Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia. Thus, he eschewed mention of his national accomplishments, such as the Louisiana Purchase and any other aspects of his presidency, in favor of his role with the young university.

Initially, some of the students arriving at the university matched the then-common picture of college students: wealthy, spoiled aristocrats with a sense of privilege which often led to brawling, or worse. This was a source of frustration for Jefferson, who assembled the students during the school's first year, on October 3, 1825, to criticize such behavior; but was too overcome to speak. He later spoke of this moment as "the most painful event" of his life.[17]

Although the frequency of such irresponsible behavior dropped after Jefferson's expression of concern, it did not die away completely. Like many universities and colleges, it experienced periodic student riots, culminating in the shooting death of Professor John A. G. Davis, Chairman of the Faculty, in 1840. This event, in conjunction with the new UVA Honor System and the growing popularity of temperance and a rise in religious affiliation in society in general, seems to have resulted in a permanent change in student attitudes toward reporting the bad behavior, and thus such behavior among students that had so greatly bothered Jefferson finally vanished.[17]

In the year of Jefferson's death in 1826, poet Edgar Allan Poe enrolled at the university, where he excelled in Latin.[18] The Raven Society, an organization named after Poe's most famous poem, continues to maintain 13 West Range, the room Poe inhabited during the single semester he attended the university.[19] He left because of financial difficulties. The School of Engineering and Applied Science opened in 1836, making UVA the first comprehensive university to open an engineering school.

Unlike the majority of Southern colleges, the university was kept open throughout the Civil War, despite its state seeing more bloodshed than any other and the near 100% conscription of the American South.[20] After Jubal Early's total loss at the Battle of Waynesboro, Charlottesville was willingly surrendered to Union forces to avoid mass bloodshed, and UVA faculty convinced George Armstrong Custer to preserve Jefferson's university.[21] Although Union troops camped on the Lawn and damaged many of the Pavilions, Custer's men left four days later without bloodshed and the university was able to return to its educational mission. However, an extremely high number of officers of both Confederacy and Union were alumni.[22] UVA produced 1,481 officers in the Confederate Army alone, including four major-generals, twenty-one brigadier-generals, and sixty-seven colonels from ten different states.[22] John S. Mosby, the infamous "Gray Ghost" and commander of the lightning-fast 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry ranger unit, had also been a UVA student.

Thanks to a grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia, tuition became free for all Virginians in the year 1875.[23] During this period, the University of Virginia remained unique in that it had no president and mandated no core curriculum from its students, who often studied in and took degrees from more than one school.[23] However, the university was also experiencing growing pains. As the original Rotunda caught fire and was gutted in 1895, there would soon be sweeping changes, much greater than merely reconstructing the Rotunda in 1899.

1900s Edwin Alderman was UVA's first president between 1904 and 1931 and instituted many reforms toward modernization.

Edwin Alderman was UVA's first president between 1904 and 1931 and instituted many reforms toward modernization.Jefferson had originally decided the University of Virginia would have no serving president. Rather, this power was to be shared by a rector and the Board of Visitors. But as the 19th century waned, it became obvious this cumbersome arrangement was incapable of adequately handling the many administrative and fundraising tasks of the growing university.[24] Edwin Alderman, who had only recently moved from his post as president of UNC-Chapel Hill since 1896 to become president of Tulane University in 1900, accepted an offer as president of the University of Virginia in 1904. His appointment was not without controversy, and national media such as Popular Science lamented the end of one of the things that made UVA unique among universities.[25]

Alderman stayed 27 years, and became known as a prolific fund-raiser, a well-known orator, and a close adviser to U.S. president and UVA alumnus Woodrow Wilson.[24] He added significantly to the University Hospital to support new sickbeds and public health research, and helped create departments of geology and forestry, the School of Education and Human Development (originally the Curry School of Education), the McIntire School of Commerce, and the summer school programs in which young Georgia O'Keeffe took part.[26] Perhaps his greatest ambition was the funding and construction of a library on a scale of millions of books, much larger than the Rotunda could bear. Delayed by the Great Depression, Alderman Library was named in his honor in 1938. Alderman, who seven years earlier had died in office en route to giving a public speech at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, is still the longest-tenured president of the university.

In 1904, UVA became the first university south of Washington, D.C. to be elected to the Association of American Universities. After a gift by Andrew Carnegie in 1909 the University of Virginia was organized into twenty-six departments across six schools including the Andrew Carnegie School of Engineering, the James Madison School of Law, the James Monroe School of International Law, the James Wilson School of Political Economy, the Edgar Allan Poe School of English and the Walter Reed School of Pathology.[16] The honorific historical names for these schools – several of which have remained as modern schools of the university – are no longer used.

In December 1953, the University of Virginia joined the Atlantic Coast Conference for athletics. At the time, UVA had a football program that had just broken through to be nationally ranked in 1950, 1951, and 1952, and consistently beat its rivals North Carolina and Virginia Tech by scores such as 34–7 and 44–0. Other sports were very competitive as well. However, the administration of Colgate Darden de-emphasized athletics, defunding the department and declining to join the ACC before being overruled by the Board of Visitors on that decision. It would take until the 1980s for the bulk of athletics programs to fully recover but approaching the year 2000 UVA was again one of the most successful all-around sports programs with NCAA national titles achieved in an array of different sports; by 2020, it had twice won the Capital One Cup for overall athletics excellence in men's sports programs.

UVA established a junior college in 1954, known today as the University of Virginia's College at Wise. George Mason University and Mary Washington University used to similarly exist as UVA's satellite campuses, but those are now wholly independent universities no longer administered by the University of Virginia.

The Academical Village and nearby Monticello became a joint World Heritage Site in 1987. Simultaneously with Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park and Chaco Culture National Historical Park, they were the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth U.S. sites designated as culturally significant to the collective interests of global humanity, coming after the Statue of Liberty and Yosemite National Park three years earlier. As such, UVA possesses the only U.S. collegiate grounds to be internationally protected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Integration, coeducation, and student dissentThe University of Virginia first admitted a few selected women to graduate studies in the late 1890s and to certain programs such as nursing and education in the 1920s and 1930s.[27] In 1944, Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg, Virginia, became the Women's Undergraduate Arts and Sciences Division of the University of Virginia. With this branch campus in Fredericksburg exclusively for women, UVA maintained its main campus in Charlottesville as near-exclusively for men, until a civil rights lawsuit in the 1960s forced it to commingle the sexes.[28] In 1970, the Charlottesville campus became fully co-educational, and in 1972 Mary Washington became an independent state university.[29] When the first female class arrived, 450 undergraduate women entered UVA, comprising 39 percent of undergraduates, while the number of men admitted remained constant. By 1999, women made up a 52 percent majority of the total student body.[27][30]

The university admitted its first black student when Gregory Swanson sued to gain entrance into the university's law school in 1950.[31] Following his successful lawsuit, a handful of black graduate and professional students were admitted during the 1950s, though no black undergraduates were admitted until 1955, and UVA did not fully integrate until the 1960s.[31] When Walter Ridley graduated with a doctorate in education, he was the first black person to graduate from UVA.[31] UVA's Ridley Scholarship Fund is named in his honor.[31]

The fight for integration and coeducation came to the foreground particularly in the late 1960s, leading up to the May Strike of 1970, in which students protested for higher black enrollment, equal access to UVA admission by undergraduate women, unionization of employees, and against the presence of armed university police and recruiters of government agencies such as the CIA and FBI on Grounds.[32]

21st century President Sullivan speaking with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in front of the Rotunda in February 2013

President Sullivan speaking with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in front of the Rotunda in February 2013Due to a continual decline in state funding for the university, today only 6 percent of its budget comes from the Commonwealth of Virginia.[33] A Charter initiative was signed into law by then-Governor Mark Warner in 2005, negotiated with the university to have greater autonomy over its own affairs in exchange for accepting this decline in financial support.[34][35]

The university welcomed Teresa A. Sullivan as its first female president in 2010.[36] Just two years later its first woman rector, Helen Dragas, engineered a forced-resignation to remove President Sullivan from office.[37][38] The attempted ouster elicited a faculty Senate vote of no confidence in Rector Dragas, and demands from student government for an explanation.[39][40] In the face of mounting pressure including alumni threats to cease contributions, and a mandate from then-Governor Robert McDonnell to resolve the issue or face removal of the entire Board of Visitors, the Board unanimously reinstated President Sullivan.[41][42][43] In 2013 and 2014, the Board passed new bylaws that made it harder to remove a president and possible to remove a rector.[44]

In November 2014, the university suspended fraternity and sorority functions pending investigation of an article by Rolling Stone concerning an alleged rape story, which was later determined to be a hoax after the story was confirmed to be false through investigation by The Washington Post.[45][46][47] The university nonetheless instituted new rules banning "pre-mixed drinks, punches or any other common source of alcohol" such as beer kegs and requiring "sober and lucid" fraternity members to monitor all parties.[48] In April 2015, Rolling Stone fully retracted the article after the Columbia School of Journalism released a report of what went wrong with the article in a scathing and discrediting report.[49][50] Even before release of the Columbia University report, the Rolling Stone story was named the "Error of the Year" by the Poynter Institute.[51] The UVA chapter of Phi Kappa Psi settled a defamation suit against Rolling Stone and received $1.65 million.[52]

In August 2017, the night before the infamous Unite the Right rally, a group of non-student and mostly non-Virginian white nationalists marched on the university's Lawn bearing torches and chanting antisemitic and Nazi slogans after the city of Charlottesville decided to remove all remaining Confederate statues from the city including one depicting Robert E. Lee.[53][54] They were met by student counter-protesters near the statue of Thomas Jefferson in front of the Rotunda, where a fight broke out.

James E. Ryan, a graduate of the University of Virginia School of Law, became the university's ninth president in August 2018.[55] His first act upon his inauguration was to announce that in-state undergraduates from families making less than $80,000 per year would receive full scholarships covering tuition, and those from families making under $30,000 would also receive free room and board.[56] Ryan was previously dean of the Harvard School of Education.

On the night of November 13, 2022, three students were killed and two others injured in a shooting on a charter bus that was returning to the campus from a play for a class trip in Washington, D.C.[57] All three fatalities were current members of the Virginia Cavaliers football team[58] and the alleged shooter was briefly a member of the team during the 2018 season.[59]

Add new comment