The Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, spanning Sydney Harbour from the central business district (CBD) to the North Shore. The view of the bridge, the harbour, and the nearby Sydney Opera House is widely regarded as an iconic image of Sydney, and of Australia itself. Nicknamed "The Coathanger" because of its arch-based design, the bridge carries rail, vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

Under the direction of John Bradfield of the New South Wales Department of Public Works, the bridge was designed and built by British firm Dorman Long of Middlesbrough, and opened in 1932. The bridge's general design, which Bradfield tasked the NSW Department of Public Works with producing, was a rough copy of the Hell Gate Bridge in New York City. The design chosen from the tender responses was original work created by Dorman Long, who leveraged some of the design from its own Tyne Bridge.

...Read more

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, spanning Sydney Harbour from the central business district (CBD) to the North Shore. The view of the bridge, the harbour, and the nearby Sydney Opera House is widely regarded as an iconic image of Sydney, and of Australia itself. Nicknamed "The Coathanger" because of its arch-based design, the bridge carries rail, vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

Under the direction of John Bradfield of the New South Wales Department of Public Works, the bridge was designed and built by British firm Dorman Long of Middlesbrough, and opened in 1932. The bridge's general design, which Bradfield tasked the NSW Department of Public Works with producing, was a rough copy of the Hell Gate Bridge in New York City. The design chosen from the tender responses was original work created by Dorman Long, who leveraged some of the design from its own Tyne Bridge.

It is the tenth longest spanning-arch bridge in the world and the tallest steel arch bridge, measuring 134 m (440 ft) from top to water level. It was also the world's widest long-span bridge, at 48.8 m (160 ft) wide, until construction of the new Port Mann Bridge in Vancouver was completed in 2012.

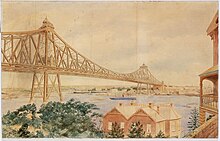

Proposed bridge from near Dawe's Point, Sydney, 1857

Proposed bridge from near Dawe's Point, Sydney, 1857 Sketches of designs submitted when tenders were called for a harbour crossing in 1900

Sketches of designs submitted when tenders were called for a harbour crossing in 1900 Three-span bridge linking Millers Point with Balls Head and Balmain, proposed by Ernest Stowe in 1922

Three-span bridge linking Millers Point with Balls Head and Balmain, proposed by Ernest Stowe in 1922There had been plans to build a bridge as early as 1814, when convict and noted architect Francis Greenway reputedly proposed to Governor Lachlan Macquarie that a bridge be built from the northern to the southern shore of the harbour.[1][2] In 1825, Greenway wrote a letter to the then "The Australian" newspaper stating that such a bridge would "give an idea of strength and magnificence that would reflect credit and glory on the colony and the Mother Country".[2]

Nothing came of Greenway's suggestions, but the idea remained alive, and many further suggestions were made during the nineteenth century. In 1840, naval architect Robert Brindley proposed that a floating bridge be built. Engineer Peter Henderson produced one of the earliest known drawings of a bridge across the harbour around 1857. A suggestion for a truss bridge was made in 1879, and in 1880 a high-level bridge estimated at £850,000 was proposed.[2]

In 1900, the Lyne government committed to building a new Central railway station and organised a worldwide competition for the design and construction of a harbour bridge, overseen by Minister for Public Works Edward William O'Sullivan.[3] Local engineer Norman Selfe submitted a design for a suspension bridge and won the second prize of £500. In 1902, when the outcome of the first competition became mired in controversy, Selfe won a second competition outright, with a design for a steel cantilever bridge. The selection board were unanimous, commenting that, "The structural lines are correct and in true proportion, and... the outline is graceful".[4] However due to an economic downturn and a change of government at the 1904 NSW State election construction never began.[citation needed]

A unique three-span bridge was proposed in 1922 by Ernest Stowe with connections at Balls Head, Millers Point, and Balmain with a memorial tower and hub on Goat Island.[5][6]

PlanningIn 1914 John Bradfield was appointed Chief Engineer of Sydney Harbour Bridge and Metropolitan Railway Construction, and his work on the project over many years earned him the legacy as the father of the bridge.[7] Bradfield's preference at the time was for a cantilever bridge without piers, and in 1916 the NSW Legislative Assembly passed a bill for such a construction, however it did not proceed as the Legislative Council rejected the legislation on the basis that the money would be better spent on the war effort.[2]

Following World War I, plans to build the bridge again built momentum.[1] Bradfield persevered with the project, fleshing out the details of the specifications and financing for his cantilever bridge proposal, and in 1921 he travelled overseas to investigate tenders. His confidential secretary Kathleen M. Butler handled all the international correspondence during his absence, her title belying her role as a technical adviser.[8][9] On return from his travels Bradfield decided that an arch design would also be suitable[2] and he and officers of the NSW Department of Public Works prepared a general design[1] for a single-arch bridge based upon New York City's Hell Gate Bridge.[10][11] In 1922 the government passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act No. 28, specifying the construction of a high-level cantilever or arch bridge across the harbour between Dawes Point and Milsons Point, along with construction of necessary approaches and electric railway lines,[2] and worldwide tenders were invited for the project.[7]

Norman Selfe's winning design at the second competition c.1903

Norman Selfe's winning design at the second competition c.1903 The Hell Gate Bridge in New York City inspired the final design of Sydney Harbour Bridge

The Hell Gate Bridge in New York City inspired the final design of Sydney Harbour BridgeAs a result of the tendering process, the government received twenty proposals from six companies; on 24 March 1924 the contract was awarded to Dorman Long & Co of Middlesbrough, England well known as the contractors who later built the similar Tyne Bridge in Newcastle Upon Tyne, for an arch bridge at a quoted price of AU£4,217,721 11s 10d.[7][2] The arch design was cheaper than alternative cantilever and suspension bridge proposals, and also provided greater rigidity making it better suited for the heavy loads expected.[2] In 1924, Kathleen Butler travelled to London to set up the project office within those of Dorman, Long & Co., "attending the most difficult and technical questions and technical questions in regard to the contract, and dealing with a mass of correspondence".[12]

Bradfield and his staff were ultimately to oversee the bridge design and building process as it was executed by Dorman Long and Co, whose Consulting Engineer, Sir Ralph Freeman of Sir Douglas Fox and Partners, and his associate Georges Imbault, carried out the detailed design and erection process of the bridge.[7] Architects for the contractors were from the British firm John Burnet & Partners of Glasgow, Scotland.[13] Lawrence Ennis, of Dorman Long, served as Director of Construction and primary onsite supervisor throughout the entire build, alongside Edward Judge, Dorman Long's Chief Technical Engineer, who functioned as Consulting and Designing Engineer.

The building of the bridge coincided with the construction of a system of underground railways beneath Sydney's CBD, known today as the City Circle, and the bridge was designed with this in mind. The bridge was designed to carry six lanes of road traffic, flanked on each side by two railway tracks and a footpath. Both sets of rail tracks were linked into the underground Wynyard railway station on the south (city) side of the bridge by symmetrical ramps and tunnels. The eastern-side railway tracks were intended for use by a planned rail link to the Northern Beaches;[14] in the interim they were used to carry trams from the North Shore into a terminal within Wynyard station, and when tram services were discontinued in 1958, they were converted into extra traffic lanes. The Bradfield Highway, which is the main roadway section of the bridge and its approaches, is named in honour of Bradfield's contribution to the bridge.

Construction Sydney Harbour Bridge under construction

Sydney Harbour Bridge under construction The arch being constructed

The arch being constructed Southbound view on the day of the official opening, 19 March 1932

Southbound view on the day of the official opening, 19 March 1932 HMAS Canberra sailing under the completed arch from which the deck is being suspended in 1930

HMAS Canberra sailing under the completed arch from which the deck is being suspended in 1930Bradfield visited the site sporadically throughout the eight years it took Dorman Long to complete the bridge. Despite having originally championed a cantilever construction and the fact that his own arched general design was used in neither the tender process nor as input to the detailed design specification (and was anyway a rough copy of the Devil's Gate bridge produced by the NSW Works Department), Bradfield subsequently attempted to claim personal credit for Dorman Long's design. This led to a bitter argument, with Dorman Long maintaining that instructing other people to produce a copy of an existing design in a document not subsequently used to specify the final construction did not constitute personal design input on Bradfield's part. This friction ultimately led to a large contemporary brass plaque being bolted very tightly to the side of one of the granite columns of the bridge to makes things clear.[15]

The official ceremony to mark the turning of the first sod occurred on 28 July 1923, on the spot at Milsons Point where two workshops to assist in building the bridge were to be constructed.[16][17]

An estimated 469 buildings on the north shore, both private homes and commercial operations, were demolished to allow construction to proceed, with little or no compensation being paid. Work on the bridge itself commenced with the construction of approaches and approach spans, and by September 1926 concrete piers to support the approach spans were in place on each side of the harbour.[16]

As construction of the approaches took place, work was also started on preparing the foundations required to support the enormous weight of the arch and loadings. Concrete and granite faced abutment towers were constructed, with the angled foundations built into their sides.[16]

Once work had progressed sufficiently on the support structures, a giant creeper crane was erected on each side of the harbour.[18] These cranes were fitted with a cradle, and then used to hoist men and materials into position to allow for erection of the steelwork. To stabilise works while building the arches, tunnels were excavated on each shore with steel cables passed through them and then fixed to the upper sections of each half-arch to stop them collapsing as they extended outwards.[16]

Arch construction itself began on 26 October 1928. The southern end of the bridge was worked on ahead of the northern end, to detect any errors and to help with alignment. The cranes would "creep" along the arches as they were constructed, eventually meeting up in the middle. In less than two years, on 19 August 1930, the two halves of the arch touched for the first time. Workers riveted both top and bottom sections of the arch together, and the arch became self-supporting, allowing the support cables to be removed. On 20 August 1930 the joining of the arches was celebrated by flying the flags of Australia and the United Kingdom from the jibs of the creeper cranes.[16][19]

Grace Cossington Smith's painting of the arch under construction.

Grace Cossington Smith's painting of the arch under construction. John Bradfield riding the first test train across the bridge on 19 January 1932

John Bradfield riding the first test train across the bridge on 19 January 1932Once the arch was completed, the creeper cranes were then worked back down the arches, allowing the roadway and other parts of the bridge to be constructed from the centre out. The vertical hangers were attached to the arch, and these were then joined with horizontal crossbeams. The deck for the roadway and railway were built on top of the crossbeams, with the deck itself being completed by June 1931, and the creeper cranes were dismantled. Rails for trains and trams were laid, and road was surfaced using concrete topped with asphalt.[16] Power and telephone lines, and water, gas, and drainage pipes were also all added to the bridge in 1931.[citation needed]

The pylons were built atop the abutment towers, with construction advancing rapidly from July 1931. Carpenters built wooden scaffolding, with concreters and masons then setting the masonry and pouring the concrete behind it. Gangers built the steelwork in the towers, while day labourers manually cleaned the granite with wire brushes. The last stone of the north-west pylon was set in place on 15 January 1932, and the timber towers used to support the cranes were removed.[20][16]

On 19 January 1932, the first test train, a steam locomotive, safely crossed the bridge.[21] Load testing of the bridge took place in February 1932, with the four rail tracks being loaded with as many as 96 New South Wales Government Railways steam locomotives positioned end-to-end.[22] The bridge underwent testing for three weeks, after which it was declared safe and ready to be opened.[16] The construction worksheds were demolished after the bridge was completed, and the land that they were on is now occupied by Luna Park.[23]

The standards of industrial safety during construction were poor by today's standards. Sixteen workers died during construction,[24] but surprisingly only two from falling off the bridge. Several more were injured from unsafe working practices undertaken whilst heating and inserting its rivets, and the deafness experienced by many of the workers in later years was blamed on the project. Henri Mallard between 1930 and 1932 produced hundreds of stills[25] and film footage[26] which reveal at close quarters the bravery of the workers in tough Depression-era conditions.[citation needed]

Interviews were conducted between 1982-1989 with a variety of tradesmen who worked on the building of the bridge. Among the tradesmen interviewed were drillers, riveters, concrete packers, boilermakers, riggers, ironworkers, plasterers, stonemasons, an official photographer, sleepcutters, engineers and draughtsmen.[27]

The total financial cost of the bridge was AU£6.25 million, which was not paid off in full until 1988.[28]

Official opening ceremonyThe bridge was formally opened on Saturday, 19 March 1932.[29] Among those who attended and gave speeches were the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game, and the Minister for Public Works, Lawrence Ennis. The Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, was to open the bridge by cutting a ribbon at its southern end.[30]

Francis de Groot cutting the ribbon at the official opening of the Bridge, 19 March 1932

Francis de Groot cutting the ribbon at the official opening of the Bridge, 19 March 1932However, just as Lang was about to cut the ribbon, a man in military uniform rode up on a horse, slashing the ribbon with his sword and opening the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the name of the people of New South Wales before the official ceremony began. He was promptly arrested.[31] The ribbon was hurriedly retied and Lang performed the official opening ceremony and Game thereafter inaugurated the name of the bridge as Sydney Harbour Bridge and the associated roadway as the Bradfield Highway. After they did so, there was a 21-gun salute and an Royal Australian Air Force flypast. The intruder was identified as Francis de Groot. He was convicted of offensive behaviour and fined £5 after a psychiatric test proved he was sane, but this verdict was reversed on appeal. De Groot then successfully sued the Commissioner of Police for wrongful arrest and was awarded an undisclosed out of court settlement. De Groot was a member of a right-wing paramilitary group called the New Guard, opposed to Lang's leftist policies and resentful of the fact that a member of the British royal family had not been asked to open the bridge.[31] De Groot was not a member of the regular army but his uniform allowed him to blend in with the real cavalry. This incident was one of several involving Lang and the New Guard during that year.[citation needed]

A similar ribbon-cutting ceremony on the bridge's northern side by North Sydney's mayor, Alderman Primrose, was carried out without incident. It was later discovered that Primrose was also a New Guard member but his role in and knowledge of the de Groot incident, if any, are unclear.[citation needed] The pair of golden scissors used in the ribbon cutting ceremonies on both sides of the bridge was also used to cut the ribbon at the dedication of the Bayonne Bridge, which had opened between Bayonne, New Jersey, and New York City the year before.[32][33]

Despite the bridge opening in the midst of the Great Depression, opening celebrations were organised by the Citizens of Sydney Organising Committee, an influential body of prominent men and politicians that formed in 1931 under the chairmanship of the lord mayor to oversee the festivities. The celebrations included an array of decorated floats, a procession of passenger ships sailing below the bridge, and a Venetian Carnival.[34] A message from a primary school in Tottenham, 515 km (320 mi) away in rural New South Wales, arrived at the bridge on the day and was presented at the opening ceremony. It had been carried all the way from Tottenham to the bridge by relays of school children, with the final relay being run by two children from the nearby Fort Street Boys' and Girls' schools. After the official ceremonies, the public was allowed to walk across the bridge on the deck, something that would not be repeated until the 50th anniversary celebrations.[2] Estimates suggest that between 300,000 and one million people took part in the opening festivities,[2] a phenomenal number given that the entire population of Sydney at the time was estimated to be 1,256,000.[35]

There had also been numerous preparatory arrangements. On 14 March 1932, three postage stamps were issued to commemorate the imminent opening of the bridge. Several songs were composed for the occasion.[36] In the year of the opening, there was a steep rise in babies being named Archie and Bridget in honour of the bridge.[37] One of three microphones used at the opening ceremony was signed by 10 local dignitaries who officiated at the event, Philip Game, John Lang, MA Davidson, Samuel Walder, D Clyne, H Primrose, Ben Howe, John Bradfield, Lawrence Ennis and Roland Kitson. It was supplied by Amalgamated Wireless Australasia, who organised the ceremony's broadcast and collected by Philip Geeves, the AWA announcer on the day. The radio is now in the collection of the Powerhouse Museum.[38]

The bridge itself was regarded as a triumph over Depression times, earning the nickname "the Iron Lung", as it kept many Depression-era workers employed.[39]

Add new comment