София

( Sofia )

Sofia ( SOH-fee-ə, SOF-; Bulgarian: София, romanized: Sofiya, IPA: [ˈsɔfijɐ] ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river and has many mineral springs, such as the Sofia Central Mineral Baths. It has a humid continental climate. Being in the centre of the Balkans, it is midway between the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea and closest to the Aegean Sea.

Known as Serdica in antiquity and Sredets in the Middle Ages, Sofia has been an area of human habitation since at least 7000 BC. The recorded history of the city begins with the attestatio...Read more

Sofia ( SOH-fee-ə, SOF-; Bulgarian: София, romanized: Sofiya, IPA: [ˈsɔfijɐ] ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river and has many mineral springs, such as the Sofia Central Mineral Baths. It has a humid continental climate. Being in the centre of the Balkans, it is midway between the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea and closest to the Aegean Sea.

Known as Serdica in antiquity and Sredets in the Middle Ages, Sofia has been an area of human habitation since at least 7000 BC. The recorded history of the city begins with the attestation of the conquest of Serdica by the Roman Republic in 29 BC from the Celtic tribe Serdi. During the decline of the Roman Empire, the city was raided by Huns, Visigoths, Avars and Slavs. In 809, Serdica was incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire by Khan Krum and became known as Sredets. In 1018, the Byzantines ended Bulgarian rule until 1194, when it was reincorporated by the reborn Bulgarian Empire. Sredets became a major administrative, economic, cultural and literary hub until its conquest by the Ottomans in 1382. From 1530 to 1836, Sofia was the regional capital of Rumelia Eyalet, the Ottoman Empire's key province in Europe. Bulgarian rule was restored in 1878. Sofia was selected as the capital of the Third Bulgarian State in the next year, ushering a period of intense demographic and economic growth.

Sofia is the 14th-largest city in the European Union. It is surrounded by mountainsides, such as Vitosha by the southern side, Lyulin by the western side, and the Balkan Mountains by the north, which makes it the third highest European capital after Andorra la Vella and Madrid. Being Bulgaria's primary city, Sofia is home of many of the major local universities, cultural institutions and commercial companies. The city has been described as the "triangle of religious tolerance". This is because three temples of three major world religions—Christianity, Islam and Judaism—are situated close together: Sveta Nedelya Church, Banya Bashi Mosque and Sofia Synagogue. This triangle was recently expanded to a "square" and includes the Catholic Cathedral of St Joseph.

Sofia has been named one of the top ten best places for startup businesses in the world, especially in information technologies. It was Europe's most affordable capital to visit in 2013. The Boyana Church in Sofia, constructed during the Second Bulgarian Empire and holding much patrimonial symbolism to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, was included onto the World Heritage List in 1979. With its cultural significance in Southeast Europe, Sofia is home to the National Opera and Ballet of Bulgaria, the National Palace of Culture, the Vasil Levski National Stadium, the Ivan Vazov National Theatre, the National Archaeological Museum, and the Serdica Amphitheatre. The Museum of Socialist Art includes many sculptures and posters that educate visitors about the lifestyle in communist Bulgaria.

The population of Sofia declined from 70,000 in the late 18th century, through 19,000 in 1870, to 11,649 in 1878, after which it began increasing. Sofia hosts some 1.24 million residents within a territory of 492 km2, a concentration of 17.9% of the country population within the 200th percentile of the country territory. The urban area of Sofia hosts some 1.54 million residents within 5723 km2, which comprises Sofia City Province and parts of Sofia Province (Dragoman, Slivnitsa, Kostinbrod, Bozhurishte, Svoge, Elin Pelin, Gorna Malina, Ihtiman, Kostenets) and Pernik Province (Pernik, Radomir), representing 5.16% of the country territory. The metropolitan area of Sofia is based upon one hour of car travel time, stretches internationally and includes Dimitrovgrad in Serbia. The metropolitan region of Sofia is inhabited by a population of 1.66 million.

O: head of river-god Strymon; R: trident.

O: head of river-god Strymon; R: trident.This coin imitates Macedonian issue from 187 to 168 BC. It was struck by Serdi tribe as their own currency.

The eastern gate of Serdica in the "Complex Ancient Serdica"Prehistory and antiquity

The eastern gate of Serdica in the "Complex Ancient Serdica"Prehistory and antiquity

The area has a history of nearly 7,000 years,[1] with the great attraction of the hot water springs that still flow abundantly in the centre of the city. The neolithic village in Slatina dating to the 5th–6th millennium BC is documented.[2] Remains from another neolithic settlement around the National Art Gallery are traced to the 3rd–4th millennium BC, which has been the traditional centre of the city ever since.[3]

The earliest tribes who settled were the Thracian Tilataei. In the 500s BC, the area became part of a Thracian state union, the Odrysian kingdom from another Thracian tribe the Odrysses.[4]

In 339 BC Philip II of Macedon destroyed and ravaged the town for the first time.[5]

The Celtic tribe Serdi gave their name to the city.[6] The earliest mention of the city comes from an Athenian inscription from the 1st century BC, attesting Astiu ton Serdon, i.e. city of the Serdi.[7] The inscription and Dio Cassius told that the Roman general Crassus subdued the Serdi and behanded the captives.[8]

In 27–29 BC, according do Dio Cassius, Pliny and Ptolemy, the region "Segetike" was attacked by Crassus, which is assumed to be Serdica, or the city of the Serdi.[9][10][11] The ancient city is located between TZUM, Sheraton Hotel and the Presidency.[3][12] It gradually became the most important Roman city of the region.[13][14] It became a municipium during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117). Serdica expanded, as turrets, protective walls, public baths, administrative and cult buildings, a civic basilica, an amphitheatre, a circus, the City council (Boulé), a large forum, a big circus (theatre), etc. were built. Serdica was a significant city on the Roman road Via Militaris, connecting Singidunum and Byzantium. In the 3rd century, it became the capital of Dacia Aureliana,[15] and when Emperor Diocletian divided the province of Dacia Aureliana into Dacia Ripensis (at the banks of the Danube) and Dacia Mediterranea, Serdica became the capital of the latter. Serdica's citizens of Thracian descent were referred to as Illyrians[5] probably because it was at some time the capital of Eastern Illyria (Second Illyria).[16]

Dated from the early 4th century, the Church of Saint George is the oldest standing edifice in Sofia.

Dated from the early 4th century, the Church of Saint George is the oldest standing edifice in Sofia.Roman emperors Aurelian (215–275)[17] and Galerius (260–311)[18] were born in Serdica.

The city expanded and became a significant political and economical centre, more so as it became one of the first Roman cities where Christianity was recognised as an official religion (under Galerius). The Edict of Toleration by Galerius was issued in 311 in Serdica by the Roman emperor Galerius, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution of Christianity. The Edict implicitly granted Christianity the status of "religio licita", a worship recognised and accepted by the Roman Empire. It was the first edict legalising Christianity, preceding the Edict of Milan by two years.

Serdica was the capital of the Diocese of Dacia (337-602).

For Constantine the Great it was 'Sardica mea Roma est' (Serdica is my Rome). He considered making Serdica the capital of the Byzantine Empire instead of Constantinople.[19] which was already not dissimilar to a tetrarchic capital of the Roman Empire.[20] In 343 AD, the Council of Sardica was held in the city, in a church located where the current 6th century Church of Saint Sophia was later built.

The city was destroyed in the 447 invasion of the Huns and laid in ruins for a century[5] It was rebuilt by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. During the reign of Justinian it flourished, being surrounded with great fortress walls whose remnants can still be seen today.

Middle Ages The 13th century lord of Sredets Kaloyan and his wife Desislava, Boyana Church

The 13th century lord of Sredets Kaloyan and his wife Desislava, Boyana ChurchSerdica became part of the First Bulgarian Empire during the reign of Khan Krum in 809, after a long siege. The fall of the strategic city prompted a major and ultimately disastrous invasion of Bulgaria by the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros I, which led to his demise at the hands of the Bulgarian army.[21] In the aftermath of the war, the city was permanently integrated in Bulgaria and became known by the Slavic name of Sredets. It grew into an important fortress and administrative centre under Krum's successor Khan Omurtag, who made it a centre of Sredets province (Sredetski komitat, Средецки комитат). The Bulgarian patron saint John of Rila was buried in Sredets by orders of Emperor Peter I in the mid 10th century.[22] After the conquest of the Bulgarian capital Preslav by Sviatoslav I of Kyiv and John I Tzimiskes' armies in 970–971, the Bulgarian Patriarch Damyan chose Sredets for his seat in the next year and the capital of Bulgaria was temporarily moved there.[23] In the second half of 10th century the city was ruled by Komit Nikola and his sons, known as the "Komitopuli". One of them was Samuil, who was eventually crowned Emperor of Bulgaria in 997. In 986, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II laid siege to Sredets but after 20 days of fruitless assaults the garrison broke out and forced the Byzantines to abandon the campaign. On his way to Constantinople, Basil II was ambushed and soundly defeated by the Bulgarians in the battle of the Gates of Trajan.[22][24]

The city eventually fell to the Byzantine Empire in 1018, following the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria. Sredets joined the uprising of Peter Delyan in 1040–1041 in a failed attempt to restore Bulgarian independence and was the last stronghold of the rebels, led by the local commander Botko.[25] During the 11th century many Pechenegs were settled down in Sofia region as Byzantine federats.

It was once again incorporated into the restored Bulgarian Empire in 1194 at the time of Emperor Ivan Asen I and became a major administrative and cultural centre.[26] Several of the city's governors were members of the Bulgarian imperial family and held the title of sebastokrator, the second highest at the time, after the tsar. Some known holders of the title were Kaloyan, Peter and their relative Aleksandar Asen (d. after 1232), a son of Ivan Asen I of Bulgaria (r. 1189–1196). In the 13th and 14th centuries Sredets was an important spiritual and literary hub with a cluster of 14 monasteries in its vicinity, that were eventually destroyed by the Ottomans. The city produced multicolored sgraffito ceramics, jewelry and ironware.[27]

In 1382/1383 or 1385, Sredets was seized by the Ottoman Empire in the course of the Bulgarian-Ottoman Wars by Lala Şahin Pasha, following a three-month siege.[28] The Ottoman commander left the following description of the city garrison: "Inside the fortress [Sofia] there is a large and elite army, its soldiers are heavily built, moustached and look war-hardened, but are used to consume wine and rakia—in a word, jolly fellows."[29]

Early modern historyFrom the 14th century till the 19th century Sofia was an important administrative center in the Ottoman Empire. It became the capital of the beylerbeylik of Rumelia (Rumelia Eyalet), the province that administered the Ottoman lands in Europe (the Balkans), one of the two together with the beylerbeylik of Anatolia. It was the capital of the important Sanjak of Sofia as well, including the whole of Thrace with Plovdiv and Edirne, and part of Macedonia with Thessaloniki and Skopje. [30]

During the initial stages of the Crusade of Varna in 1443, it was occupied by Hungarian forces for a short time in 1443, and the Bulgarian population celebrated a mass Saint Sofia Church. Following the defeat of the crusader forces in 1444, the city's Christians faced persecution. In 1530 Sofia became the capital of the Ottoman province (beylerbeylik) of Rumelia for about three centuries. During that time Sofia was the largest import-export-base in modern-day Bulgaria for the caravan trade with the Republic of Ragusa. In the 15th and 16th century, Sofia was expanded by Ottoman building activity. Public investments in infrastructure, education and local economy brought greater diversity to the city. Amongst others, the population consisted of Muslims, Bulgarian and Greek speaking Orthodox Christians, Armenians, Georgians, Catholic Ragusans, Jews (Romaniote, Ashkenazi and Sephardi), and Romani people.[28] The 16th century was marked by a wave of persecutions against the Bulgarian Christians, a total of nine became New Martyrs in Sofia and were sainted by the Orthodox Church, including George the New (1515), Sophronius of Sofia (1515), George the Newest (1530), Nicholas of Sofia (1555) and Terapontius of Sofia (1555).[31]

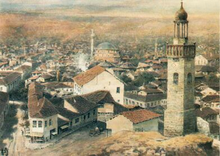

Sofia in mid-19th-century

Sofia in mid-19th-centuryWhen it comes to the cityscape, 16th century sources mention eight Friday mosques, three public libraries, numerous schools, 12 churches, three synagogues, and the largest bedesten (market) of the Balkans.[28] Additionally, there were fountains and hammams (bathhouses). Most prominent churches such as Saint Sofia and Saint George were converted into mosques, and a number of new ones were constructed, including Banya Bashi Mosque built by the renowned Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan. In total there were 11 big and over 100 small mosques by the 17th century.[32][33] In 1610 the Vatican established the See of Sofia for Catholics of Rumelia, which existed until 1715 when most Catholics had emigrated.[34] There was an important uprising against Ottoman rule in Sofia, Samokov and Western Bulgaria in 1737.

Sofia entered a period of economic and political decline in the 17th century, accelerated during the period of anarchy in the Ottoman Balkans of the late 18th and early 19th century, when local Ottoman warlords ravaged the countryside. 1831 Ottoman population statistics show that 42% of the Christians were non-taxpayers in the kaza of Sofia and the amount of middle-class and poor Christians were equal.[35] Since the 18th century the beylerbeys of Rumelia often stayed in Bitola, which became the official capital of the province in 1826. Sofia remained the seat of a sanjak (district). By the 19th century the Bulgarian population had two schools and seven churches, contributing to the Bulgarian National Revival. In 1858 Nedelya Petkova created the first Bulgarian school for women in the city. In 1867 was inaugurated the first chitalishte in Sofia – a Bulgarian cultural institution. In 1870 the Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski established a revolutionary committee in the city and in the neighbouring villages. Following his capture in 1873, Vasil Levski was transferred and hanged in Sofia by the Ottomans.

Modern and contemporary historyDuring the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, Suleiman Pasha threatened to burn the city in defence, but the foreign diplomats Leandre Legay, Vito Positano, Rabbi Gabriel Almosnino and Josef Valdhart refused to leave the city thus saving it. Many Bulgarian residents of Sofia armed themselves and sided with the Russian forces.[36] Sofia was relieved (see Battle of Sofia) from Ottoman rule by Russian forces under Gen. Iosif Gurko on 4 January 1878. It was proposed as a capital by Marin Drinov and was accepted as such on 3 April 1879. By the time of its liberation the population of the city was 11,649.[37]

Most mosques in Sofia were destroyed in that war, seven of them destroyed in one night in December 1878 when a thunderstorm masked the noise of the explosions arranged by Russian military engineers.[38][39] Following the war, the great majority of the Muslim population left Sofia.[28]

The allied bombing of Sofia in World War II in 1944

The allied bombing of Sofia in World War II in 1944For a few decades after the liberation, Sofia experienced large population growth, mainly by migration from other regions of the Principality (Kingdom since 1908) of Bulgaria, and from the still Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace.

In 1900, the first electric lightbulb in the city was turned on.[40]

In the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria was fighting alone practically all of its neighbouring countries. When the Romanian Army entered Vrazhdebna in 1913, then a village 11 kilometres (7 miles) from Sofia, now a suburb,[41] this prompted the Tsardom of Bulgaria to capitulate.[citation needed] During the war, Sofia was flown by the Romanian Air Corps, which engaged on photoreconnaissance operations and threw propaganda pamphlets to the city. Thus, Sofia became the first capital on the world to be overflown by enemy aircraft.[42]

During the Second World War, Bulgaria declared war on the US and UK on 13 December 1941 and in late 1943 and early 1944 the US and UK Air forces conducted bombings over Sofia. As a consequence of the bombings thousands of buildings were destroyed or damaged including the Capital Library and thousands of books. In 1944 Sofia and the rest of Bulgaria was occupied by the Soviet Red Army and within days of the Soviet invasion Bulgaria declared war on Nazi Germany.

In 1945, the communist Fatherland Front took power. The transformations of Bulgaria into the People's Republic of Bulgaria in 1946 and into the Republic of Bulgaria in 1990 marked significant changes in the city's appearance. The population of Sofia expanded rapidly due to migration from rural regions. New residential areas were built in the outskirts of the city, like Druzhba, Mladost and Lyulin.

During the Communist Party rule, a number of the city's most emblematic streets and squares were renamed for ideological reasons, with the original names restored after 1989.[43]

The Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum, where Dimitrov's body had been preserved in a similar way to the Lenin mausoleum, was demolished in 1999.

Add new comment