Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; Greek: Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (Πέργαμος), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located 26 kilometres (16 mi) from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river Caicus (modern-day Bakırçay) and northwest of the modern city of Bergama, Turkey.

During the Hellenistic period, it became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon in 281–133 BC under the Attalid dynasty, who transformed it into one of the major cultural centres of the Greek world. Many remains of its monuments can still be seen and especially the masterpiece of the Pergamon Altar. Pergamon was the northernmost of the seven churches of Asia cited in the New Testament Book of Revelation.

The city is...Read more

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; Greek: Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (Πέργαμος), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located 26 kilometres (16 mi) from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river Caicus (modern-day Bakırçay) and northwest of the modern city of Bergama, Turkey.

During the Hellenistic period, it became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon in 281–133 BC under the Attalid dynasty, who transformed it into one of the major cultural centres of the Greek world. Many remains of its monuments can still be seen and especially the masterpiece of the Pergamon Altar. Pergamon was the northernmost of the seven churches of Asia cited in the New Testament Book of Revelation.

The city is centered on a 335-metre-high (1,100 ft) mesa of andesite, which formed its acropolis. This mesa falls away sharply on the north, west, and east sides, but three natural terraces on the south side provide a route up to the top. To the west of the acropolis, the Selinus River (modern Bergamaçay) flows through the city, while the Cetius river (modern Kestelçay) passes by to the east.

Pergamon was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2014.

Settlement of Pergamon can be detected as far back as the Archaic period, thanks to modest archaeological finds, especially fragments of pottery imported from the west, particularly eastern Greece and Corinth, which date to the late 8th century BC.[1] Earlier habitation in the Bronze Age cannot be demonstrated, although Bronze Age stone tools are found in the surrounding area.[2]

The earliest mention of Pergamon in literary sources comes from Xenophon's Anabasis, since the march of the Ten Thousand under Xenophon's command ended at Pergamon in 400/399 BC.[3] Xenophon, who calls the city Pergamos, handed over the rest of his Greek troops (some 5,000 men according to Diodorus) to Thibron, who was planning an expedition against the Persian satraps Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus, at this location in March 399 BC. At this time Pergamon was in the possession of the family of Gongylos from Eretria, a Greek favourable to the Achaemenid Empire who had taken refuge in Asia Minor and obtained the territory of Pergamon from Xerxes I, and Xenophon was hosted by his widow Hellas.[4]

In 362 BC, Orontes, satrap of Mysia, used Pergamon as his base for an unsuccessful revolt against the Persian Empire.[5] Only with Alexander the Great were Pergamon and the surrounding area removed from Persian control. There are few traces of the pre-Hellenistic city, since in the following period the terrain was profoundly changed and the construction of broad terraces involved the removal of almost all earlier structures. Parts of the temple of Athena, as well as the walls and foundations of the altar in the sanctuary of Demeter, go back to the fourth century.

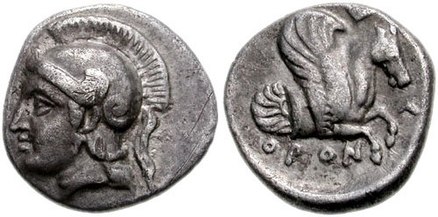

![Possible coinage of the Greek ruler Gongylos, wearing the Persian cap on the reverse, as ruler of Pergamon for the Achaemenid Empire. Pergamon, Mysia, circa 450 BC. The name of the city ΠΕΡΓ ("PERG"), appears for the first on this coinage, and is the first evidence for the name of the city.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/MYSIA%2C_Pergamon._Mid_5th_century_BCE.jpg/434px-MYSIA%2C_Pergamon._Mid_5th_century_BCE.jpg)

Image of Philetaerus on a coin of Eumenes I

Image of Philetaerus on a coin of Eumenes I The Kingdom of Pergamon, shown at its greatest extent in 188 BC

The Kingdom of Pergamon, shown at its greatest extent in 188 BC Over-life-size portrait head, probably of Attalus I

Over-life-size portrait head, probably of Attalus ILysimachus, King of Thrace, took possession in 301 BC, and the town was enlarged by his lieutenant Philetaerus. In 281 BC the kingdom of Thrace collapsed and Philetaerus became an independent ruler, founding the Attalid dynasty. His family ruled Pergamon from 281 until 133 BC: Philetaerus 281–263; Eumenes I 263–241; Attalus I 241–197; Eumenes II 197–159; Attalus II 159–138; and Attalus III 138–133. Philetaerus controlled only Pergamon and its immediate environs, but the city acquired much new territory under Eumenes I. In particular, after the Battle of Sardis in 261 BC against Antiochus I, Eumenes was able to appropriate the area down to the coast and some way inland. Despite this increase of his domain, Eumenes did not take a royal title. In 238 his successor Attalus I defeated the Galatians, to whom Pergamon had paid tribute under Eumenes I.[7] Attalus thereafter declared himself leader of an entirely independent Pergamene kingdom.

The Attalids became some of the most loyal supporters of Rome in the Hellenistic world. Attalus I allied with Rome against Philip V of Macedon, during the first and second Macedonian Wars. In the Roman–Seleucid War, Pergamon joined the Romans' coalition against Antiochus III, and was rewarded with almost all the former Seleucid domains in Asia Minor at the Peace of Apamea in 188 BC. The kingdom's territories thus reached their greatest extent. Eumenes II supported Rome again in the Third Macedonian War, but the Romans heard rumours of his conducting secret negotiations with their opponent Perseus of Macedon. On this basis, Rome denied any reward to Pergamon and attempted to replace Eumenes with the future Attalus II, who refused to cooperate. These incidents cost Pergamon its privileged status with the Romans, who granted it no further territory.

Nevertheless, under the brothers Eumenes II and Attalus II, Pergamon reached its apex and was rebuilt on a monumental scale. It had retained the same dimensions for a long interval after its founding by Philetaerus, covering c. 21 hectares (52 acres). After 188 BC a massive new city wall was constructed, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) long and enclosing an area of approximately 90 hectares (220 acres).[8] The Attalids' goal was to create a second Athens, a cultural and artistic hub of the Greek world. They remodeled their Acropolis after the Acropolis in Athens, and the Library of Pergamon was renowned as second only to the Library of Alexandria. Pergamon was also a flourishing center for the production of parchment, whose name is a corruption of pergamenos, meaning "from Pergamon". Despite this etymology, parchment had been used in Asia Minor long before the rise of the city; the story that it was invented by the Pergamenes, to circumvent the Ptolemies' monopoly on papyrus production, is not true.[9] Surviving epigraphic documents show how the Attalids supported the growth of towns by sending in skilled artisans and by remitting taxes. They allowed the Greek cities in their domains to maintain nominal independence, and sent gifts to Greek cultural sites like Delphi, Delos, and Athens. The two brothers Eumenes II and Attalus II displayed the most distinctive trait of the Attalids: a pronounced sense of family without rivalry or intrigue - rare amongst the Hellenistic dynasties.[10] Attalus II bore the epithet 'Philadelphos', 'he who loves his brother', and his relations with Eumenes II were compared to the harmony between the mythical brothers Cleobis and Biton.[11]

When Attalus III died without an heir in 133 BC, he bequeathed the whole of Pergamon to Rome. This was challenged by Aristonicus, who claimed to be Attalus III's brother and led an armed uprising against the Romans with the help of Blossius, a famous Stoic philosopher. For a period he enjoyed success, defeating and killing the Roman consul P. Licinius Crassus and his army, but he was defeated in 129 BC by the consul M. Perperna. The Attalid kingdom was divided between Rome, Pontus, and Cappadocia, with the bulk of its territory becoming the new Roman province of Asia. The city itself was declared free and served briefly as capital of the province, before this distinction was transferred to Ephesus.

Roman period Mithridates VI, portrait in the Louvre

Mithridates VI, portrait in the LouvreIn 88 BC, Mithridates VI Eupator made Pergamon his headquarters in his first war against Rome, in which he was defeated. The victorious Romans deprived Pergamon of all its benefits and of its status as a free city. Henceforth the city was required to pay tribute and accommodate and supply Roman troops, and the property of many of the inhabitants was confiscated. Imported Pergamene goods were among the luxuries enjoyed by Lucullus. The members of the Pergamene aristocracy, especially Diodorus Pasparus in the 70s BC, used their own possessions to maintain good relationships with Rome, by acting as donors for the development of the city. Numerous honorific inscriptions indicate Pasparus' work and his exceptional position in Pergamon at this time.[12]

Pergamon still remained a famous city, and was the seat of a conventus (regional assembly). Its neocorate, granted by Augustus, was the first manifestation of the imperial cult in the province of Asia. Pliny the Elder refers to the city as the most important in the province[13] and the local aristocracy continued to reach the highest circles of power in the 1st century AD, like Aulus Julius Quadratus who was consul in 94 and 105.

Pergamon in the Roman province of Asia, 90 BC

Pergamon in the Roman province of Asia, 90 BCYet it was only under Trajan and his successors that a comprehensive redesign and remodelling took place, with the construction of a Roman 'new city' at the base of the Acropolis. The city was the first in the province to receive a second neocorate, from Trajan in AD 113/4. Hadrian raised the city to the rank of metropolis in 123 and thereby elevated it above its local rivals, Ephesus and Smyrna. An ambitious building programme was carried out: massive temples, a stadium, a theatre, a huge forum and an amphitheatre were constructed. In addition, at the city limits the shrine to Asclepius (the god of healing) was expanded into a lavish spa. This sanctuary grew in fame and was considered one of the most famous healing centers of the Roman world.

A model of the acropolis of Pergamon, showing the situation in the 2nd century CE

A model of the acropolis of Pergamon, showing the situation in the 2nd century CEIn the middle of the 2nd century Pergamon was one of the largest cities in the province, and had around 200,000 inhabitants. Galen, the most famous physician of antiquity aside from Hippocrates, was born at Pergamon and received his early training at the Asclepieion. At the beginning of the 3rd century Caracalla granted the city a third neocorate, but a decline had already set in. The economic strength of Pergamon collapsed during the crisis of the Third Century, as the city was badly damaged in an earthquake in 262 and was sacked by the Goths shortly thereafter. In late antiquity, it experienced a limited economic recovery.

Byzantine periodIn AD 663/4, Pergamon was captured by raiding Arabs for the first time.[14] As a result of the ongoing Arab threat, the area of settlement retracted to the acropolis, which the Emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) fortified[14] with a 6-meter-thick (20 ft) wall built of spolia.

During the middle Byzantine period, the city was part of the Thracesian Theme,[14] and from the time of Leo VI the Wise (r. 886–912) of the Theme of Samos.[15] 7th-century sources attest an Armenian community in Pergamon, probably formed of refugees from the Muslim conquests; this community produced the emperor Philippicus (r. 711–713).[14][15] In 716, Pergamon was sacked again by the armies of Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik. It was again rebuilt and refortified after the Arabs abandoned their Siege of Constantinople in 717–718.[14][15]

Pergamon suffered from the Seljuk invasion of western Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Attacks in 1109 and 1113 largely destroyed the city, which was only rebuilt, by Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180), around 1170. It likely became the capital of the new theme of Neokastra, established by Manuel.[14][15] Under Isaac II Angelos (r. 1185–1195), the local see was promoted to a metropolitan bishopric, having previously been a suffragan diocese of the Metropolis of Ephesus.[15]

After the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, Pergamon became part of the Empire of Nicaea.[15] When Emperor Theodore II Laskaris (r. 1254–1285) visited Pergamon in 1250, he was shown the house of Galen, but he saw that the theatre had been destroyed and, except for the walls which he paid some attention to, only the vaults over the Selinus seemed noteworthy to him. The monuments of the Attalids and the Romans were only plundered ruins by this time.

With the expansion of the Anatolian beyliks, Pergamon was absorbed into the beylik of Karasids shortly after 1300, and then conquered by the Ottoman beylik.[15] The Ottoman Sultan Murad III had two large alabaster urns transported from the ruins of Pergamon and placed on two sides of the nave in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.[16]

Add new comment