नाणेघाट

( Naneghat )

Naneghat, also referred to as Nanaghat or Nana Ghat (IAST: Nānāghaṭ), is a mountain pass in the Western Ghats range between the Konkan coast and the ancient town of Junnar in the Deccan plateau. The pass is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Pune and about 165 kilometres (103 mi) east from Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was a part of an ancient trading route, and is famous for a major cave with Sanskrit inscriptions in Brahmi script and Middle Indo-Aryan dialect. These inscriptions have been dated between the 2nd and the 1st century BCE, and attributed to the Satavahana dynasty era. The inscriptions are notable for linking the Vedic and Hinduism deities, mentioning some Vedic srauta rituals and of names that provide historical information about the ancient Satavahanas. The inscriptions present the world's oldest numeration symbols for "2, 4, 6, 7, and 9" that resemble modern era numerals, more closely those found in modern Nagar...Read more

Naneghat, also referred to as Nanaghat or Nana Ghat (IAST: Nānāghaṭ), is a mountain pass in the Western Ghats range between the Konkan coast and the ancient town of Junnar in the Deccan plateau. The pass is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Pune and about 165 kilometres (103 mi) east from Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was a part of an ancient trading route, and is famous for a major cave with Sanskrit inscriptions in Brahmi script and Middle Indo-Aryan dialect. These inscriptions have been dated between the 2nd and the 1st century BCE, and attributed to the Satavahana dynasty era. The inscriptions are notable for linking the Vedic and Hinduism deities, mentioning some Vedic srauta rituals and of names that provide historical information about the ancient Satavahanas. The inscriptions present the world's oldest numeration symbols for "2, 4, 6, 7, and 9" that resemble modern era numerals, more closely those found in modern Nagari and Hindu-Arabic script.

The Naneghat caves, likely an ancient rest stop for travellers.[1]

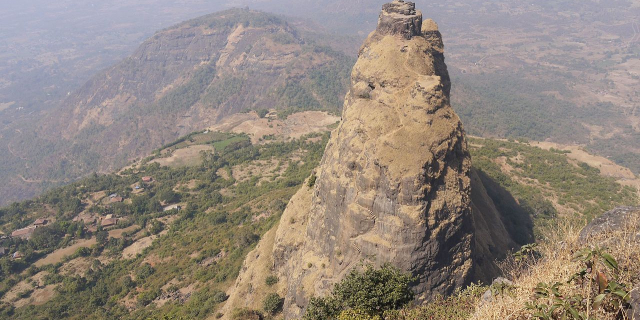

The Naneghat caves, likely an ancient rest stop for travellers.[1]During the reign of the Satavahana (c. 200 BCE – 190 CE), the Naneghat pass was one of the trade routes. It connected the Konkan coast communities with Deccan high plateau through Junnar.[2] Literally, the name nane means "coin" and ghat means "pass". The name is given because this path was used as a tollbooth to collect toll from traders crossing the hills. According to Charles Allen, there is a carved stone that from distance looks like a stupa, but is actually a two-piece carved stone container by the roadside to collect tolls.[3]

The scholarship on the Naneghat Cave inscription began after William Sykes found them while hiking during the summer of 1828.[4][5] Neither an archaeologist nor epigraphist, his training was as a statistician and he presumed that it was a Buddhist cave temple. He visited the site several times and made eye-copy (hand drawings) of the script panel he saw on the left and the right side of the wall. He then read a paper to the Bombay Literary Society in 1833 under the title, Inscriptions of the Boodh caves near Joonur,[4] later co-published with John Malcolm in 1837.[6] Sykes believed that the cave's "Boodh" (Buddhist) inscription showed signs of damage both from the weather elements as well as someone crudely incising to desecrate it.[3] He also thought that the inscription was not created by a skilled artisan, but someone who was in a hurry or not careful.[3] Sykes also noted that he saw stone seats carved along the walls all around the cave, likely because the cave was meant as a rest stop or shelter for those traveling across the Western Ghats through the Naneghat pass.[1][3][4]

William Sykes made an imperfect eye-copy of the inscription in 1833, to bring it to scholarly attention.[7]

William Sykes made an imperfect eye-copy of the inscription in 1833, to bring it to scholarly attention.[7]Sykes proposed that the inscription were ancient Sanskrit because the statistical prevalence rate of some characters in it was close to the prevalence rate of same characters in then known ancient Sanskrit inscriptions.[4][8] This suggestion reached the attention of James Prinsep, whose breakthrough in deciphering Brahmi script led ultimately to the inscription's translation. Much that Sykes guessed was right, the Naneghat inscription he had found was indeed one of the oldest Sanskrit inscriptions.[3] He was incorrect in his presumption that it was a Buddhist inscription because its translation suggested it was a Hindu inscription.[9] The Naneghat inscription were a prototype of the refined Devanagari to emerge later.[3]

Georg Bühler published the first version of a complete interpolations and translation in 1883.[10] He was preceded by Bhagvanlal Indraji, who in a paper on numismatics (coins) partially translated it and remarked that the Naneghat and coin inscriptions provide insights into ancient numerals.[10][11]

Date Naneghat Pass Entrance

Naneghat Pass EntranceThe inscriptions are attributed to a queen of the Satavahana dynasty. Her name was either Nayanika or Naganika, likely the wife of king Satakarni. The details suggest that she was likely the queen mother, who sponsored this cave after the death of her husband, as the inscription narrates many details about their life together and her son being the new king.[12]

The Naneghat cave inscriptions have been dated by scholars to the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE. Most scholars date it to the early 1st-century BCE, some to 2nd-century BCE, a few to even earlier.[13][12][14] Sircar dated it to the second half of the 1st-century BCE.[15] Upinder Singh and Charles Higham date 1st century BCE.[16][17]

The Naneghat records have proved very important in establishing the history of the region. Vedic Gods like Dharma Indra, Chandra and Surya are mentioned here. The mention of Samkarsana (Balarama) and Vasudeva (Krishna) indicate the prevalence of Bhagavata tradition of Hinduism in the Satavahana dynasty.

Add new comment