Άγιο Όρος

( Monastic community of Mount Athos )The monastic community of Mount Athos is an Eastern Orthodox community of monks in Greece who hold the status of an autonomous region as well as the combined rights of a decentralized administration, a region and a municipality, with a territory encompassing the distal part of the Athos peninsula including Mount Athos. The bordering proximal part of the peninsula belongs to the regular Aristotelis community in Central Macedonia.

In modern Greek, the community is commonly referred to as Agio Oros (Άγιο Όρος) translating to 'Holy Mountain', while Oros Athos (Greek: Όρος Άθως) is used to denote the physical mountain and Hersonissos tou Atho (Χερσόνησος του Άθω) in respect to the peninsula.

The community includes 20 monasteries and t...Read more

The monastic community of Mount Athos is an Eastern Orthodox community of monks in Greece who hold the status of an autonomous region as well as the combined rights of a decentralized administration, a region and a municipality, with a territory encompassing the distal part of the Athos peninsula including Mount Athos. The bordering proximal part of the peninsula belongs to the regular Aristotelis community in Central Macedonia.

In modern Greek, the community is commonly referred to as Agio Oros (Άγιο Όρος) translating to 'Holy Mountain', while Oros Athos (Greek: Όρος Άθως) is used to denote the physical mountain and Hersonissos tou Atho (Χερσόνησος του Άθω) in respect to the peninsula.

The community includes 20 monasteries and the settlements on which they depend. The monasteries house around 2,000 Eastern Orthodox monks from Greece and many other countries, including Eastern Orthodox countries such as Romania, Moldova, Georgia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Serbia and Russia, who live an ascetic life at Athos, isolated from the rest of the world. The Athonite monasteries feature a rich collection of well-preserved artifacts, rare books, ancient documents, and artworks of immense historical value, and Mount Athos has been listed as a World Heritage Site since 1988.

Although Mount Athos is legally part of the European Union like the rest of Greece, the Monastic community institutions have a special jurisdiction, which was reaffirmed during the admission of Greece to the European Community (precursor to the EU). This empowers the monastic community's authorities to restrict the free movement of people and goods in its territory; in particular, only males are allowed to enter, while women and most female animals are banned from Mount Athos by religious tradition of the community that lives there.

A Byzantine watch tower, protecting the dock (αρσανάς, arsanás) of Xeropotamou monastery

A Byzantine watch tower, protecting the dock (αρσανάς, arsanás) of Xeropotamou monasteryThe chroniclers Theophanes the Confessor (end of 8th century) and Georgios Kedrenos (11th century) wrote that the 726 eruption of the Thera volcano was visible from Mount Athos, indicating that it was inhabited at the time. The historian Genesios recorded that monks from Athos participated at the seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea of 787. Following the Battle of Thasos in 829, Athos was deserted for some time due to the destructive raids of the Cretan Saracens. Around 860, the monk Euthymios the Younger came to Athos from Bithynia.[1]

Emperor Nicephorus Phocas

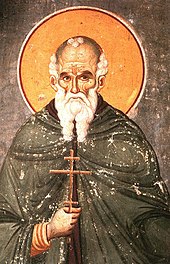

Emperor Nicephorus Phocas Athanasios the Athonite

Athanasios the Athonite Holy Mount Athos: The Holy Mount Athos: Sheltering the Oldest Orthodox Literary Treasures (1926), by Alphonse Mucha, The Slav Epic

Holy Mount Athos: The Holy Mount Athos: Sheltering the Oldest Orthodox Literary Treasures (1926), by Alphonse Mucha, The Slav EpicIn 958, the monk Athanasios the Athonite (Άγιος Αθανάσιος ο Αθωνίτης) arrived on Mount Athos. In 962 he built the large central church of the Protaton in Karyes. In the next year, with the support of his friend Emperor Nicephorus Phocas, the monastery of Great Lavra was founded, still the largest and most prominent of the twenty monasteries existing today. It enjoyed the protection of the Byzantine emperors during the following centuries, and its wealth and possessions grew considerably.[2] Alexios I Komnenos, emperor from 1081 to 1118, gave Mount Athos complete autonomy from the Ecumenical Patriarch and the Bishop of Ierissos, and also exempted the monasteries from taxation. Furthermore, until 1312, the Protos of Karyes was directly appointed by the Byzantine Emperor.[3]

The first charter of Mount Athos, signed in 972 by Emperor John Tzimiskes, Athanasius the Athonite, and 46 hegumenoi, is currently kept at the Protaton in Karyes. It is also known as the Tragos ('goat'), since it was written on goatskin parchment.[4] The second charter or typikon of Mount Athos was written in September 1045 and signed by 180 hegumenoi. Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos ratified the typikon with an imperial chrysobull in June 1046. This charter was also the first official document that referred to Mount Athos as the "Holy Mountain".[3]

From 985 to 1287,[5] there was a Benedictine monastery on Mount Athos (between Magisti Lavra and Philotheou Karakallou[6]) known as Amalphion after the people of Amalfi who founded it.[7] The monastery was founded with support of John the Iberian, a Georgian and the founder of the Iviron Monastery, and is thought to have influenced Latin Christian monasticism and piety.[5]

The Fourth Crusade in the 13th century brought new Roman Catholic overlords, which forced the monks to complain and ask for the intervention of Pope Innocent III until the restoration of the Byzantine Empire. The peninsula was raided by Catalan mercenaries in the 14th century in the so-called Catalan vengeance due to which the entry of people of Catalan origin was prohibited until 2005. The 14th century also saw the theological conflict over the hesychasm practised on Mount Athos and defended by Gregory Palamas (Άγιος Γρηγόριος ο Παλαμάς). In late 1371 or early 1372 the Byzantines defeated an Ottoman attack on Athos.[2]

Serbian era and influencesSerbian lords of the Nemanjić dynasty offered financial support to the monasteries of Mount Athos, while some of them also made pilgrimages and became monks there. Stefan Nemanja helped build the Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos together with his son Archbishop Saint Sava in 1198.[8][9]

From 1342 until 1372 Mount Athos was under Serbian administration. Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan helped Mount Athos with many large donations to all monasteries. In the charter of emperor Stefan Dušan to the Monastery of Hilandar[10] the Emperor gave to the monastery Hilandar direct rule over many villages and churches, including the church of Svetog Nikole u Dobrušti in Prizren, the church of Svetih Arhanđela in Štip, the Church of Svetog Nikole in Vranje and surrounding lands and possessions. He also gave large possessions and donations to the Karyes Hermitage of St. Sabas and the Holy Archangels in Jerusalem.[11] Empress Helena, wife of the Emperor Stefan Dušan, was among the very few women allowed to visit and stay in Mount Athos, to protect her from the plague.[12][full citation needed] She avoided breaking the ban by not touching the ground for her entire visit, being constantly carried in a hand carriage.[13]

Thanks to the donations by Dušan, the Serbian monastery of Hilandar was enlarged to more than 10,000 hectares, thus having the largest possessions on Mount Athos among other monasteries, and occupying 1/3 of the area. Serbian nobleman Antonije Bagaš, together with Nikola Radonja, bought and restored the ruined Agiou Pavlou monastery between 1355 and 1365, becoming its abbot.[14]

The time of the Serbian Empire was a prosperous period for Hilandar and of other monasteries in Mount Athos and many of them were restored and rebuilt and significantly enlarged.[12][full citation needed]

Serbian princess Mara Branković was the second Serbian woman that was granted permissions to visit the area. At the end of the 15th century five monasteries on Mount Athos had Serbian monks and were under the Serbian Prior: Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, Ayiou Dionysiou and Hilandar[15]

Ottoman eraThe Byzantine Empire ceased to exist in the 15th century and the Ottoman Empire took its place.[16]

From the account of the Rus' pilgrim Isaiah, by the end of the 15th century monasteries in Mount Athos represented monastic communities from large and diverse parts of the Balkans (Slavic, Albanian, Greek). Other monasteries listed by him bear no such designations. In particular, Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, Ayiou Dionysiou, and Chilandariou were Serbian; Karakalou and Philotheou were Albanian; Panteleïmon was Russian; Simonopetra was Bulgarian; Great Lavra, Vatopedi, Pantokratoros and Stavronikita were Greek; and Zographou, Kastamonitou, Xeropotamou, Koutloumousiou, Xenophontos, Iviron and Protaton did not bear any designation.[17]

View of the area around Vatopedi monastery

View of the area around Vatopedi monasterySultan Selim I was a substantial benefactor of the Xeropotamou monastery. In 1517, he issued a fatwa and a Hatt-i Sharif ("noble edict") that "the place, where the Holy Gospel is preached, whenever it is burned or even damaged, shall be erected again". He also endowed privileges to the Abbey and financed the construction of the dining area and underground of the Abbey as well as the renovation of the wall paintings in the central church that were completed between the years 1533 and 1541.[18]

This new way of monastic organization was an emergency measure taken by the monastic communities to counter their harsh economic environment. Contrary to the cenobitic system, monks in idiorrhythmic communities have private property and work for themselves, bearing sole responsibility for acquiring food and other necessities; they dine separately in their cells, only meeting with other monks at church. At the same time, the monasteries' abbots were replaced by committees and at Karyes the Protos was replaced by a four-member committee.[19]

In 1749, with the establishment of the Athonite Academy near Vatopedi monastery, the local monastic community took a leading role in the modern Greek Enlightenment movement of the 18th century.[20] This institution offered high level education, especially under Eugenios Voulgaris, where ancient philosophy and modern physical science were taught.[21]

Late modern timesIn modern times after the end of Ottoman rule new Serbian kings from the Obrenović dynasty and Karađorđević dynasty and the new bourgeois class resumed their support of Mount Athos.[22]

In November 1912, during the First Balkan War, the Ottomans were forced out by the Greek Navy.[23]

In June 1913, a small Russian fleet, consisting of the gunboat Donets and the transport ships Tsar and Kherson, delivered the archbishop of Vologda, and a number of troops to Mount Athos to intervene in the theological controversy over imiaslavie (a Russian Orthodox movement).

Maryse Choisy entered the monastic community in the 1920s disguised as a sailor. She later wrote about her escapade in Un mois chez les hommes ("A Month with Men").[24] In the 1930s, Aliki Diplarakou dressed as a man and snuck into the monastic community. Her stunt was discussed in a 13 July 1953 Time magazine article entitled "The Climax of Sin".[25]

A monk named Mihailo Tolotos is claimed to have lived in the monastic community from c. 1855–1856 to 1938. On October 29, 1938, the American community newspaper Edinburg Daily Courier of Edinburg, Indiana reported that Tolotos had died at the age of 82. Reportedly, Tolotos had never seen a woman in his life, his mother having died in childbirth and he was brought up in the monastery by the monks.[26] His 1938 death was again mentioned in January 7, 1949, edition of Raleigh Register in an Nixon Furniture Company advertisement, saying he lived a secluded life in the monastery, suggesting he may have never left the monastery.[27]

Following the outbreak of World War II, Time magazine described during the German invasion of Greece in 1941 a bombing attack near the monastic community, "The Stukas swooped across the Aegean skies like dark, dreadful birds, but they dropped no bombs on the monks of Mount Athos".[28] During the German occupation of Greece, the Epistassia formally asked Adolf Hitler to place the monastic community under his personal protection. Hitler agreed and received the title "High Protector of the Holy Mountain" (German: Hoher Protektor des heiligen Berges) from the monks. The monastic community was able to avoid significant damage during the war.[29][better source needed]

Contemporary timesAfter the war, a Special Double Assembly passed the constitutional charter of the monastic community, which was then ratified by the Greek Parliament.

In 1953, Cora Miller, an American Fulbright Program teacher, landed briefly along with two other women, stirring up a controversy among the local monks.[30]

After the dissolution of the Yugoslav Communist regime and Socialist Yugoslavia many presidents and prime ministers of Serbia visited Mount Athos.[31]

A 2003 resolution of the European Parliament requested the lifting of the ban for violating "the universally recognised principle of gender equality".[32]

On 26 May 2008, five Moldovans illegally entered Greece by way of Turkey, ending up in the monastic community. Four of these migrants were women. The monks forgave them for trespassing and informed them that the area was forbidden to females.[33]

In 2008 a group of Greek women contravened the 1,000-year ban on females on the mount during a protest after five monasteries laid claim to 8,100 hectares (20,000 acres) of land on the nearby Chalkidiki peninsula. About 10 women jumped over the border fence spent about 20 minutes on the monastery territory, being joined by MP Litsa Ammanatidou-Paschalidou.[34]

In 2018, the monastic community became an issue in Greece-Russia relations when the Greek government denied entry to Russian clerics headed for the monastic community. The media reported allegations that the Russian Federation was using the monastic community as a base for intelligence operations in Greece.[35] In October 2018, the Moscow Patriarchate broke communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate and banned its adherents from visiting sites controlled by Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, including the monastic community, in retaliation for his decision to grant autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.[36][37][38]

In the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and related sanctions, in 2022 the money-laundering authority of Greece launched an investigation into the suspicious transfer of large funds from Russia to Russia-friendly monasteries and monks at Mount Athos. Several senior Russian officials had visited Mount Athos in the preceding months.[39]

Add new comment