Kakadu National Park

Kakadu National Park is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia, 171 km (106 mi) southeast of Darwin. It is a World Heritage Site. Kakadu is also gazetted as a locality, covering the same area as the national park, with 313 people recorded living there in the 2016 Australian census.

Kakadu National Park is located within the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory, covering an area of 19,804 km2 (7,646 sq mi), extending nearly 200 kilometres (124 mi) from north to south and over 100 kilometres (62 mi) from east to west. It is roughly the size of Wales or one-third the size of Tasmania, and is the second-largest national park in Australia, after the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert National Park. Most of the region is owned by the Aboriginal traditional owners, who have occupied the land for around 60,000 years and, today, manage the park jointly with Parks Australia. It is highly ecologically and bio...Read more

Kakadu National Park is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia, 171 km (106 mi) southeast of Darwin. It is a World Heritage Site. Kakadu is also gazetted as a locality, covering the same area as the national park, with 313 people recorded living there in the 2016 Australian census.

Kakadu National Park is located within the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory, covering an area of 19,804 km2 (7,646 sq mi), extending nearly 200 kilometres (124 mi) from north to south and over 100 kilometres (62 mi) from east to west. It is roughly the size of Wales or one-third the size of Tasmania, and is the second-largest national park in Australia, after the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert National Park. Most of the region is owned by the Aboriginal traditional owners, who have occupied the land for around 60,000 years and, today, manage the park jointly with Parks Australia. It is highly ecologically and biologically diverse, hosting a wide range of habitats and flora and fauna. It also includes a rich heritage of Aboriginal rock art, including highly significant sites, such as Ubirr. Kakadu is fully protected by the EPBC Act.

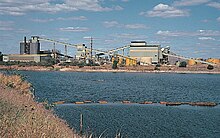

The Ranger Uranium Mine site, one of the most productive uranium mines in the world until it ceased operations in January 2021, is surrounded by the park.

Domestic Asian water buffalo, which are now an established feral population and invasive environmental pests, were released into the area in the late 19th century. Feral pigs, cats, red foxes and rabbits are further examples of invasive species, all of which compete with and wreak havoc upon the sensitive, unique ecosystems of the Northern Territory, and of the whole of Australia. These species were intentionally brought to the continent by the early settlers, pastoralists, and missionaries. The European presence, albeit less than in more populated regions (on the east and west coasts), was still felt. In Kakadu, missionaries established a mission at Oenpelli (present-day Gunbalanya) in 1925. A few pastoralists, crocodile-hunters and wood cutters also made a living in the area at various times up until the early 20th century. The area was progressively given protected status from the 1970s onward.

The name Kakadu probably originates from the mispronunciation of Gaagudju, which is the name of an Aboriginal language spoken in the north-western part of the park. Explorer Baldwin Spencer had incorrectly ascribed the name "Kakadu tribe" to the people living in the Alligator Rivers area[1][2]

Aboriginal peoples have occupied the Kakadu area continuously for around 60,000 years.[3] Kakadu National Park is renowned for the richness of its Aboriginal cultural sites. There are more than 5,000 recorded art sites illustrating Aboriginal culture over thousands of years. The archaeological sites demonstrate Aboriginal occupation for at least 20,000 and possibly up to 40,000 years.[citation needed]

The arrival of non-Indigenous people ExplorersThe Chinese, Malays and Portuguese all claim to have been the first non-Aboriginal explorers of Australia's north coast. The first surviving written account comes from the Dutch. In 1623 Jan Carstenszoon made his way west across the Gulf of Carpentaria to what is believed to be Groote Eylandt. Abel Tasman is the next documented explorer to visit this part of the coast in 1644. He was the first person to record European contact with Aboriginal people. Almost a century later Matthew Flinders surveyed the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1802 and 1803.[citation needed]

The Ubirr Aboriginal rock art site

The Ubirr Aboriginal rock art sitePhillip Parker King, an English navigator entered the Gulf of Carpentaria between 1818 and 1822. During this time he named the three Alligator Rivers after the large numbers of crocodiles, which he mistook for alligators.

Ludwig Leichhardt was the first land-based European explorer to visit the Kakadu region, in 1845 on his route from Moreton Bay in Queensland to Port Essington in the Northern Territory. He followed Jim Jim Creek down from the Arnhem Land escarpment, then went down the South Alligator before crossing to the East Alligator and proceeding north.

Rock art painting at Ubirr

Rock art painting at UbirrIn 1862, John McDouall Stuart travelled along the south-western boundary of Kakadu but did not see any people.[citation needed]

The first non-Aboriginal people to visit and have sustained contact with Aboriginal people in northern Australia were the Macassans from Sulawesi and other parts of the Indonesian archipelago. They travelled to northern Australia every wet season, probably from the last quarter of the seventeenth century, in sailing boats called praus. Their main aim was to harvest trepang (sea cucumber), turtle shell, pearls and other prized items to trade in their homeland. Aboriginal people were involved in harvesting and processing the trepang, and in collecting and exchanging the other goods.

There is no evidence that the Macassans spent time on the coast of Kakadu but there is evidence of some contact between Macassan culture and Aboriginal people of the Kakadu area. Among the artefacts from archaeological digs in the park are glass and metal fragments that probably came from the Macassans, either directly or through trade with the Cobourg Peninsula people.

The British attempted a number of settlements on the northern Australian coast in the early part of the nineteenth century: Fort Dundas on Melville Island in 1824; Fort Wellington at Raffles Bay in 1829; and Victoria Settlement (Port Essington) on the Cobourg Peninsula in 1838. They were anxious to secure the north of Australia before the French or Dutch, who had colonised islands further north. The British settlements were all subsequently abandoned for a variety of reasons, such as lack of water and fresh food, sickness and isolation.[citation needed]

Buffalo hunters Water buffalo in the wetlands

Water buffalo in the wetlandsWater buffalo had a large influence on the Kakadu region as well. By the 1880s the number of buffaloes released from early settlements had increased to such an extent that commercial harvesting of hides and horns was economically viable. The industry began on the Adelaide River, close to Darwin, and moved east to the Mary River and Alligator Rivers regions.

Most of the buffalo hunting and skin curing was done in the dry season, between June and September, when buffaloes congregated around the remaining billabongs. During the wet season hunting ceased because the ground was too muddy to pursue buffalo and the harvested hides would rot. The buffalo-hunting industry became an important employer of Aboriginal people during the dry-season months.

MissionariesMissionaries also had a large influence on the Aboriginal people of the Alligator Rivers region, many of whom lived and were schooled at missions in their youth. Two missions were set up in the region in the early part of the century. Kapalga Native Industrial Mission was established near the South Alligator River in 1899, but lasted only four years. The Oenpelli Mission began in 1925, when the Church of England Missionary Society accepted an offer from the Northern Territory Administration to take over the area, which had been operated as a dairy farm. The Oenpelli Mission operated for 50 years.[citation needed]

Salt water crocodile in KakaduPastoralists

Salt water crocodile in KakaduPastoralists

The pastoral industry made a cautious start in the Top End. Pastoral leases in the Kakadu area were progressively abandoned from 1889, because the Victoria River and the Barkly Tablelands proved to be better pastoral regions.

In southern Kakadu, much of Goodparla and Gimbat was claimed in the mid-1870s by three pastoralists, Roderick, Travers and Sergison. The leases were subsequently passed on to a series of owners, all of whom were unable for one reason or another to make a go of it. In 1987 both stations were acquired by the Commonwealth and incorporated in Kakadu National Park.

A sawmill at Nourlangie Camp was begun by Chinese operators, probably before World War I, to mill stands of cypress pine in the area. After World War II a number of small-scale ventures, including dingo shooting and trapping, brumby shooting, crocodile shooting, tourism and forestry, began.[citation needed]

Nourlangie Camp was again the site of a sawmill in the 1950s, until the local stands of cypress pine were exhausted. In 1958 it was converted into a safari camp for tourists. Soon after, a similar camp was started at Patonga and at Muirella Park. Clients were flown in for recreational buffalo and crocodile hunting and fishing.

Crocodile hunters often made use of the bush skills of Aboriginal people. By imitating a wallaby's tail hitting the ground, Aboriginal hunters could attract crocodiles, making it easier to shoot the animals. Using paperbark rafts, they would track the movement of a wounded crocodile and retrieve the carcass for skinning. The skins were then sold to make leather goods. Aboriginal people became less involved in commercial hunting of crocodiles once the technique of spotlight shooting at night developed. Freshwater crocodiles have been protected by law since 1964 and saltwater crocodiles since 1971.[citation needed]

Mining The Ranger Uranium Mine

The Ranger Uranium MineThe first mineral discoveries in the Top End were associated with the construction of the Overland Telegraph line between 1870 and 1872, in the Pine Creek – Adelaide River area. A series of short mining booms followed. The construction of the North Australia Railway line (1889–1976) gave more permanency to the mining camps, and places such as Burrundie and Pine Creek became permanent settlements. Small-scale gold mining began at Imarlkba, near Barramundi Creek, and Mundogie Hill in the 1920s and at Moline (previously called Eureka and Northern Hercules mine), south of the park, in the 1930s. The mines employed a few local Aboriginal people.[citation needed]

In 1953, uranium was discovered along the headwaters of the South Alligator River valley. Thirteen small but rich uranium mines operated in the following decade, at their peak in 1957 employing over 150 workers. Early in the 1970s large uranium deposits were discovered at Ranger, Jabiluka and Koongarra. Following receipt of a formal proposal to develop the Ranger site, the Commonwealth Government initiated an inquiry into land use in the Alligator Rivers region. The Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry (known as the Fox inquiry) recommended, among other things, that mining begin at the Ranger site, that consideration be given to the future development of the Jabiluka and Koongarra sites, and that a service town be built.[citation needed]

Gold mining was proposed in the late 1980s at Coronation Hill (Guratba).[4] This site had initially been excluded from the park but was added as part of stage 3. Its mining was blocked following environmental and social campaigns. Despite internal disagreement the then Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, vetoed mining in a Cabinet Meeting[5] in May 1991.

In the mid 1990s a similar debate over additional uranium mining at Jabiluka[6] was prevented by a campaign and blockade initiated by the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation.[7] The Ranger uranium mine closed in 2021.[8]

Add new comment