Էջմիածնի Մայր Տաճար

( Etchmiadzin Cathedral )

Etchmiadzin Cathedral (Armenian: Էջմիածնի մայր տաճար, romanized: Ēǰmiaçni mayr tač̣ar) is the mother church of the Armenian Apostolic Church, located in the city dually known as Etchmiadzin (Ejmiatsin) and Vagharshapat, Armenia. It is usually considered the first cathedral built in ancient Armenia, and often regarded the oldest cathedral in the world.

The original church was built in the early fourth century—between 301 and 303 according to tradition—by Armenia's patron saint Gregory the Illuminator, following the adoption of Christianity as a state religion by King Tiridates III. It was built over a pagan temple, symbolizing the conversion from paganism to Christianity. The core of the current building was built in 483/4 by Vahan Mamikonian after the cathedral was severely damaged in a Persian invasion. From its foundation unti...Read more

Etchmiadzin Cathedral (Armenian: Էջմիածնի մայր տաճար, romanized: Ēǰmiaçni mayr tač̣ar) is the mother church of the Armenian Apostolic Church, located in the city dually known as Etchmiadzin (Ejmiatsin) and Vagharshapat, Armenia. It is usually considered the first cathedral built in ancient Armenia, and often regarded the oldest cathedral in the world.

The original church was built in the early fourth century—between 301 and 303 according to tradition—by Armenia's patron saint Gregory the Illuminator, following the adoption of Christianity as a state religion by King Tiridates III. It was built over a pagan temple, symbolizing the conversion from paganism to Christianity. The core of the current building was built in 483/4 by Vahan Mamikonian after the cathedral was severely damaged in a Persian invasion. From its foundation until the second half of the fifth century, Etchmiadzin was the seat of the Catholicos, the supreme head of the Armenian Church.

Although never losing its significance, the cathedral subsequently suffered centuries of virtual neglect. In 1441 it was restored as catholicosate and remains as such to this day. Since then the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin has been the administrative headquarters of the Armenian Church. Etchmiadzin was plundered by Shah Abbas I of Persia in 1604, when relics and stones were taken out of the cathedral to New Julfa in an effort to undermine Armenians' attachment to their land. Since then the cathedral has undergone a number of renovations. Belfries were added in the latter half of the seventeenth century and in 1868 a sacristy (museum and room of relics) was constructed at the cathedral's east end. Today, it incorporates styles of different periods of Armenian architecture. Diminished during the early Soviet period, Etchmiadzin revived again in the second half of the twentieth century, and under independent Armenia.

As the center of Armenian Christianity, Etchmiadzin has been an important location in Armenia not only religiously, but also politically and culturally. A major pilgrimage site, it is one of the most visited places in the country. Along with several important early medieval churches located nearby, the cathedral was listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000.

In the early fourth century the Kingdom of Armenia, under Tiridates III, become the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as a state religion.[a] Armenian church tradition places the cathedral's foundation between 301 and 303.[7] It was built near the royal palace in what was then the Armenian capital of Vagharshapat,[8] on the site of a pagan temple, which was dated by Alexander Sahinian to the Urartian period.[9] Although no historical sources point to a pre-Christian place of worship in its place, a granite Urartian stele dated to the 8th-6th centuries BC was excavated under the main altar in the 1950s.[10][11][b] Also excavated under the altar was an amphora, which has been interpreted to have been a part of a fire temple.[13][c]

In his History of the Armenians, Agathangelos narrates the legend of the cathedral's foundation. Armenia's patron saint Gregory the Illuminator had a divine vision descending from heaven and striking the earth with a golden hammer to show where the cathedral should be built. Later tradition associated the figure with Jesus Christ,[19] hence the name of Etchmiadzin (էջ ēĵ "descent" + մի mi "only" + -ա- -a- (linking element) + ծին tsin "begotten"),[20] which translates to "the Descent of the Only-Begotten [Son of God]"[21][22] or "Descended the Only Begotten".[23] However, the name Etchmiadzin did not come into use until the 15th century,[7] while earlier sources call it "Cathedral of Vagharshapat."[d] The Feast of the Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin (Տոն Կաթողիկե Սբ. Էջմիածնի) is celebrated by the Armenian Church 64 days after Easter, during which a hymn, written by the 8th century Catholicos Sahak III, retelling St. Gregory's vision, is sung.[26]

as proposed by Alexander Sahinian (1966)[27]

Malachia Ormanian suggested that the cathedral was built in 303 within seven months because the building was not huge and probably, partially made of wood. He also argued that the foundation of the preexisting temple could have been preserved.[28] Vahagn Grigoryan dismisses these dates as implausible and states that at least several years were needed for its construction. He cites Agathangelos, who does not mention the cathedral in an episode that took place in 306 and suggests the usage of the span of 302 to 325—the reign of Gregory the Illuminator as Catholicos as the dates of the cathedral's construction.[28]

Archaeological excavations in 1955–56 and 1959, led by Alexander Sahinian, uncovered the remains of the original fourth-century building, including two levels of pillar bases below the current ones and a narrower altar apse under the present one.[8][11] Based on these findings, Sahinian asserted that the original church had been a three-naved[29] vaulted basilica,[8] similar to the basilicas of Tekor, Ashtarak and Aparan (Kasagh).[30] However, other scholars, have rejected Sahinian's view.[31] Among them, Suren Yeremian and Armen Khatchatrian held that the original church had been in the form of a rectangle with a dome supported by four pillars.[29] Stepan Mnatsakanian suggested that the original building had been a "canopy erected on a cross [plan]," while Vahagn Grigoryan proposes what Mnatsakanian describes as an "extreme view,"[32] that the cathedral has been essentially in the same form as it is today.[29]

Reconstruction and decline The ground plan of the cathedral after the 5th century reconstruction

The ground plan of the cathedral after the 5th century reconstructionAccording to Faustus of Byzantium, the cathedral and the city of Vagharshapat were almost completely destroyed during the invasion of Sasanian King Shapur II in the 360s[33] (circa 363).[21][34] Due to Armenia's unfavorable economic conditions, the cathedral was renovated only partially by Catholicoi Nerses the Great (r. 353–373) and Sahak Parthev (r. 387–439).[9]

In 387, Armenia was partitioned between the Roman and Sasanian Empires. Etchmiadzin became part of the Persian-controlled east, under the rule of Armenian vassal kings until 428, when the Armenian Kingdom was dissolved.[35] In 450, in an attempt to impose Zoroastrianism on Armenians, Sasanian King Yazdegerd II built a fire temple inside the cathedral.[36] The pyre of the fire temple was unearthed under the altar of the east apse during the excavations in the 1950s.[11][e]

By the last quarter of the fifth century the cathedral was dilapidated.[37] According to Ghazar Parpetsi, it was rebuilt from the foundations by marzban (governor) of Persian Armenia Vahan Mamikonian in 483/4,[38] when the country was relatively stable,[39] following the struggle for religious freedom against Persia.[38] Most[37] researchers have concluded that, thus, the church was converted into cruciform church and mostly took its current form.[f] The new church was very different from the original one and "consisted of quadric-apsidal hall built of dull, grey stone containing four free-standing cross-shaped pillars disdained to support a stone cupola." The new cathedral was "in the form of a square enclosing a Greek cross and contains two chapels, one on either side of the east apse."[21]

Although the seat of the Catholicos was transferred to Dvin sometime in the 460s–470s[41] or 484,[42][43] the cathedral never lost its significance and remained "one of the greatest shrines of the Armenian Church."[44] The last known renovations until the 15th century were made by Catholicos Komitas in 618 (according to Sebeos) and Catholicos Nerses III (r. 640–661).[21][11] In 982 the cross of the cathedral was reportedly removed by an Arab emir.[40]

Over the course of these centuries of neglect, the cathedral deteriorated to such an extent that it inspired the renowned archbishop Stepanos Orbelian to compose one of his better known poems, "Lament on Behalf of the Cathedral", in 1300.[45][g] In the poem, which tells about the consequences of the Mongol and Mamluk invasions of Armenia and Cilicia, Orbelian portrays Etchmiadzin Cathedral "as a woman in mourning, contemplating her former splendor and exhorting her children to return to their homeland [...] and restore its glory."[48]

From revival to plunderFollowing the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in 1375, the See of Sis experienced decline and disarray. The Catholicosate of Aghtamar and the locally influential Syunik bishops enhanced the importance of the region around Etchmiadzin. In 1441 a general council of several hundred religious figures met in Etchmiadzin and voted to reestablish a catholicosate there.[49] The cathedral was restored by Catholicos Kirakos (Cyriacus) between 1441 and 1443.[21] At that time Etchmiadzin was under the control of the Turkic Kara Koyunlu, but in 1502, Safavid Iran gained control of parts of Armenia, including Etchmiadzin, and granted the Armenian Church some privileges.[50]

A detail from a 1691 map of Armenia by Eremya Çelebi, an Ottoman Armenian traveler.

A detail from a 1691 map of Armenia by Eremya Çelebi, an Ottoman Armenian traveler.During the 16th and 17th centuries, Armenia suffered from its location between Persia and Ottoman Turkey, and the conflicts between those two empires. Concurrently with the deportation of up to 350,000 Armenians into Persia by Shah Abbas I as part of the scorched earth policy during the war with the Ottoman Empire,[51][52] Etchmiadzin was plundered in 1604.[50]

The Shah wanted to "dispel Armenian hopes of returning to their homeland"[53] by moving the religious center of the Armenians to Iran[54] in order to provide Persia with a strong Armenian presence.[55] He wanted to destroy the cathedral and have it physically transferred to the newly founded Armenian community of New Julfa near the royal capital of Isfahan.[54][56] Shah Abbas offered the prospective new cathedral in New Julfa to the Pope.[56] Etchmiadzin was not moved, possibly because of the high costs.[57] In the event, only some important stones—the altar, the stone where Jesus Christ descended according to tradition, and Armenian Church's holiest relic,[58] the Right Arm of Gregory the Illuminator—were moved to New Julfa.[39] They were incorporated in the local Armenian St. Georg Church when it was built in 1611.[53][59] Fifteen stones from Etchmiadzin still remain at St. Georg.[57]

An engraving of Etchmiadzin in the late 17th century by Jean Chardin (from 1811 edition)․[60]17th–18th centuries

An engraving of Etchmiadzin in the late 17th century by Jean Chardin (from 1811 edition)․[60]17th–18th centuries

Since 1627, the cathedral underwent a major renovation under Catholicos Movses (Moses), when the dome, ceiling, roof, foundations and paving were repaired.[39] At this time, cells for monks, a guesthouse and other structures were built around the cathedral.[11] Additionally, a wall was built around the cathedral, making it a fort-like complex.[39]

The renovation works were interrupted by the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1635–36, during which the cathedral remained intact.[11] The renovations resumed under Catholicos Pilippos (1632–55), who built new cells for monks and renovated the roof.[11] During this century, belfries were added to many Armenian churches.[40] In 1653–54, he started the construction of the belfry in the western wing of Etchmiadzin Cathedral. It was completed in 1658 by Catholicos Hakob IV Jugayetsi.[39] Decades later, in 1682, Catholicos Yeghiazar constructed smaller bell towers with red tuff turrets on the southern, eastern, and northern wings.[21][11]

The renovations of Etchmiadzin continued during the 18th century. In 1720, Catholicos Astvatsatur and then, in 1777–83 Simeon I of Yerevan took actions in preserving the cathedral.[11] In 1770, Simeon I established a publishing house near Etchmiadzin, the first in Armenia.[61][21] During Simeon's reign, the monastery was completely walled and separated from the city of Vagharshapat.[7] Catholicos Ghukas (Lucas) continued the renovations in 1784–86.[11]

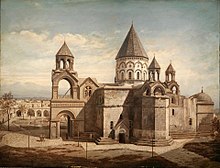

A 1783 watercolor of the churches of Etchmiadzin by Mikhail Matveevich Ivanov.[62][h]

A 1783 watercolor of the churches of Etchmiadzin by Mikhail Matveevich Ivanov.[62][h]From left to right: Hripsime, Gayane, Etchmiadzin Cathedral, and Shoghakat.[64]

Painting of the cathedral by an unknown European artist (1870s)Russian takeover

Painting of the cathedral by an unknown European artist (1870s)Russian takeover

The Russian Empire gradually penetrated Transcaucasia by the early 19th century. Persia's Erivan Khanate, in which Etchmiadzin was located, became an important target for the Russians. In June 1804, during the Russo-Persian War (1804–13), the Russian troops led by General Pavel Tsitsianov tried to take Etchmiadzin, but failed.[65][66] A few days after the attempt, the Russians returned to Etchmiadzin, where they caught a different Persian force by surprise and routed them.[66][65] Tsitsianov's forces entered Etchmiadzin, which, according to Auguste Bontems-Lefort, a contemporary French military envoy to Persia, they looted, seriously damaging the Armenian religious buildings.[66] Shortly after, the Russians were forced to withdraw from the area as a result of the successful Persian defense of Erivan.[66][67][68] According to Bontems-Lefort, the Russian behaviour at Etchmiadzin contrasted with that of the Persian king, who treated the local Christian population with respect.[66]

On 13 April 1827, during the Russo-Persian War (1826–28), Etchmiadzin was captured by the Russian General Ivan Paskevich's troops without fight and was formally annexed by Russia, with the Persian-controlled parts of Armenia, roughly corresponding to the territory of the modern Republic of Armenia (also known as Eastern Armenia), according to the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay.[69]

The cathedral prospered under Russian rule, despite the suspicions that the Imperial Russian government had about Etchmiadzin becoming a "possible center of the Armenian nationalist sentiment."[21] Formally, Etchmiadzin became the religious center of the Armenians living within the Russian Empire by the 1836 statute or constitution (polozhenie).[70]

In 1868, Catholicos Gevorg (George) IV made the last major alteration to the cathedral by adding a sacristy (museum and room of relics) to its east end.[21] In 1874, he established the Gevorgian Seminary, a theological school-college located on the cathedral's premises.[71][21] Catholicos Markar I undertook the restoration of the interior of the cathedral in 1888.[40]

20th century and on The monastery of Etchmiadzin in the early 20th century with Mount Ararat in the background

The monastery of Etchmiadzin in the early 20th century with Mount Ararat in the background Etchmiadzin, c. 1910

Etchmiadzin, c. 1910In 1903, the Russian government issued an edict to confiscate the properties of the Armenian Church, including the treasures of Etchmiadzin.[21] Russian policemen and soldiers entered and occupied the cathedral.[72][73] Due to popular resistance and the personal defiance of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian, the edict was canceled in 1905.[70]

During the Armenian genocide, the cathedral of Etchmiadzin and its surrounding became a major center for Turkish Armenian refugees. At the end of 1918, there were about 70,000 refugees in the Etchmiadzin district.[74] A hospital and an orphanage within the cathedral's grounds were established and maintained by the U.S.-based Armenian Near East Relief by 1919.[21]

In the spring of 1918 the cathedral was in danger of an attack by the Turks.[75] Prior to the May 1918 Battle of Sardarabad, which took place just miles away from the cathedral, the civilian and military leadership of Armenia suggested Catholicos Gevorg (George) V to leave for Byurakan for security purposes, but he refused.[76][77] The Armenian forces eventually repelled the Turkish offensive and set the foundations of the First Republic of Armenia.

Soviet period SuppressionAfter two years of independence, Armenia was Sovietized in December 1920. During the 1921 February Uprising Etchmiadzin was briefly (until April) taken over by the nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation, which had dominated the pre-Soviet Armenian government between 1918 and 1920.[78]

In December 1923, the southern apse of the cathedral collapsed. It was restored under Toros Toramanian's supervision in what was the first case of restoration of an architectural monument in Soviet Armenia.[79]

The Soviet government issued a postage stamp depicting the cathedral in 1978.

The Soviet government issued a postage stamp depicting the cathedral in 1978.During the Great Purge and the radical state atheist policies in the late 1930s, the cathedral was a "besieged institution as the campaign was underway to eradicate religion."[80] The repressions climaxed when Catholicos Khoren I was murdered in April 1938 by the NKVD.[81] In August of that year, the Armenian Communist Party decided to close down the monastery, but the central Soviet government seemingly did not approve of such a measure.[82] Isolated from the outside world, the cathedral barely continued to function and its administrators were reduced to some twenty people.[21] It was reportedly the only church in Soviet Armenia not to have been seized by the Communist government.[83] The dissident anti-Soviet Armenian diocese in the US wrote that "the great cathedral became a hollow monument."[84]

RevivalEtchmiadzin slowly recovered its religious importance during World War II. The Holy See's official magazine resumed publication in 1944, while the seminary was reopened in September 1945.[85] In 1945 Catholicos Gevorg VI was elected after the seven-year vacancy of the position. The number of baptisms conducted at Etchmiadzin rose greatly: from 200 in 1949 to around 1,700 in 1951.[86] Nevertheless, the cathedral's role was downplayed by the Communist official circles. "For them the ecclesiastical Echmiadzin belongs irrevocably to the past, and even if the monastery and the cathedral are occasionally the scene of impressive ceremonies including the election of a new catholicos, this has little importance from the communist point of view," wrote Walter Kolarz in 1961.[87]

Etchmiadzin revived under Catholicos Vazgen I since the Khrushchev Thaw in the mid-1950s, following Stalin's death. Archaeological excavations were held in 1955–56 and in 1959; the cathedral underwent a major renovation during this period.[40][11] Wealthy diaspora benefactors, such as Calouste Gulbenkian and Alex Manoogian, financially assisted the renovation of the cathedral.[40] Gulbenkian alone provided $400,000.[88]

Independent Armenia An aerial view of the cathedral undergoing restoration in 2021

An aerial view of the cathedral undergoing restoration in 2021In 2000[89] Etchmiadzin underwent a renovation prior to the celebrations of the 1700th anniversary of the Christianization of Armenia in 2001.[40] Its metal roof was replaced by stone slabs.[90] In 2003 the 1700th anniversary of the consecration of the cathedral was celebrated by the Armenian Church.[91] Catholicos Karekin II declared 2003 the Year of Holy Etchmiadzin.[92] In September of that year an academic conference on the cathedral was held at the Pontifical Residence.[93]

The latest renovation of the cathedral began in 2012,[89] with a focus on strengthening and restoring the dome and the roof.[94]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

![[node:title]](/sites/default/files/styles/640x320/public/pla/images/2021-03/Monasterio_Khor_Virap%2C_Armenia%2C_2016-10-01%2C_DD_25.jpeg?h=7c882872&itok=TSlbC6VX)

Add new comment