Canada

Context of Canada

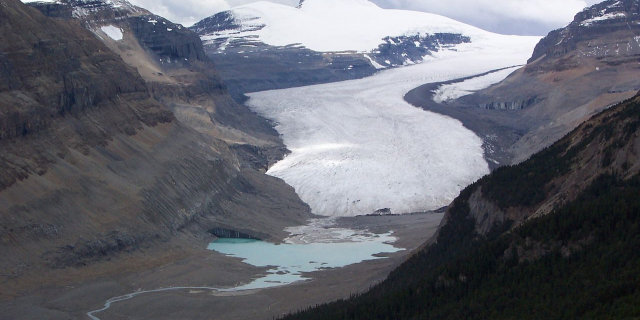

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's second-largest country by total area, with the world's longest coastline. It is characterized by a wide range of both meteorologic and geological regions. The country is sparsely inhabited, with 95 percent of the population residing south of the 55th parallel in urban areas. Canada's capital is Ottawa and its three largest metropolitan areas are Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

Indigenous peoples have continuously inhabited what is now Canada for thousands of years. Beginning in the 16th century, British and French expeditions explored and later settled along the Atlantic coast. As a consequence of various armed conflicts, France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America in 1763. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies thro...Read more

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's second-largest country by total area, with the world's longest coastline. It is characterized by a wide range of both meteorologic and geological regions. The country is sparsely inhabited, with 95 percent of the population residing south of the 55th parallel in urban areas. Canada's capital is Ottawa and its three largest metropolitan areas are Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

Indigenous peoples have continuously inhabited what is now Canada for thousands of years. Beginning in the 16th century, British and French expeditions explored and later settled along the Atlantic coast. As a consequence of various armed conflicts, France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America in 1763. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the United Kingdom, highlighted by the Statute of Westminster, 1931, and culminating in the Canada Act 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Canada is a parliamentary liberal democracy and a constitutional monarchy in the Westminster tradition. The country's head of government is the prime minister, who holds office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the elected House of Commons and is "called upon" by the governor general, representing the monarch of Canada, the head of state. The country is a Commonwealth realm and is officially bilingual (English and French) in the federal jurisdiction. It is very highly ranked in international measurements of government transparency, quality of life, economic competitiveness, innovation, and education. It is one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations, the product of large-scale immigration. Canada's long and complex relationship with the United States has had a significant impact on its history, economy, and culture.

A highly developed country, Canada has one of the highest nominal per capita income globally and its advanced economy ranks among the largest in the world, relying chiefly upon its abundant natural resources and well-developed international trade networks. Canada is part of several major international and intergovernmental institutions or groupings including the United Nations, NATO, G7, Group of Ten, G20, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Trade Organization (WTO), Commonwealth of Nations, Arctic Council, Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and Organization of American States.

More about Canada

- Currency Canadian dollar

- Native name Canada

- Calling code +1

- Internet domain .ca

- Mains voltage 120V/60Hz

- Democracy index 9.24

- Population 40000000

- Area 9984670

- Driving side right

- Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples in present-day Canada include the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis,[1] the last being of mixed descent who originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations people married European settlers and subsequently developed their own identity.[1]

The first inhabitants of North America are generally hypothesized to have migrated from Siberia by way of the Bering land bridge and arrived at least 14,000 years ago.[2][3] The Paleo-Indian archeological sites at Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are two of the oldest sites of human habitation in Canada.[4] The characteristics of Indigenous societies included permanent settlements, agriculture, complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[5][6] Some of these cultures had collapsed by the time European explorers arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries and have only been discovered through archeological investigations.[7]

...Read moreIndigenous peoplesRead lessIndigenous peoples in present-day Canada include the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis,[1] the last being of mixed descent who originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations people married European settlers and subsequently developed their own identity.[1]

The first inhabitants of North America are generally hypothesized to have migrated from Siberia by way of the Bering land bridge and arrived at least 14,000 years ago.[2][3] The Paleo-Indian archeological sites at Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are two of the oldest sites of human habitation in Canada.[4] The characteristics of Indigenous societies included permanent settlements, agriculture, complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[5][6] Some of these cultures had collapsed by the time European explorers arrived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries and have only been discovered through archeological investigations.[7]

Linguistic areas of North American Indigenous peoples at the time of European contact

Linguistic areas of North American Indigenous peoples at the time of European contactThe Indigenous population at the time of the first European settlements is estimated to have been between 200,000[8] and two million,[9] with a figure of 500,000 accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[10] As a consequence of European colonization, the Indigenous population declined by forty to eighty percent and several First Nations, such as the Beothuk, disappeared.[11] The decline is attributed to several causes, including the transfer of European diseases, such as influenza, measles, and smallpox, to which they had no natural immunity,[8][12] conflicts over the fur trade, conflicts with the colonial authorities and settlers, and the loss of Indigenous lands to settlers and the subsequent collapse of several nations' self-sufficiency.[13][14]

Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful.[15] First Nations and Métis peoples played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting European coureur des bois and voyageurs in their explorations of the continent during the North American fur trade.[16] These early European interactions with First Nations would change from friendship and peace treaties to the dispossession of Indigenous lands through treaties.[17][18] From the late 18th century, European Canadians forced Indigenous peoples to assimilate into a western Canadian society.[19] These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with forced integration,[20] health-care segregation,[21] and displacement.[22] A period of redress is underway, which started with the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada by the Government of Canada in 2008.[23] This includes recognition of past colonial injustices and settlement agreements and betterment of racial discrimination issues, such as addressing the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women.[24][25]

European colonization Map of territorial claims in North America by 1750, before the French and Indian War, which was part of the greater worldwide conflict known as the Seven Years' War (1756 to 1763). Possessions of Britain (pink), New France (blue), and Spain (orange; California, Pacific Northwest, and Great Basin not indicated)

Map of territorial claims in North America by 1750, before the French and Indian War, which was part of the greater worldwide conflict known as the Seven Years' War (1756 to 1763). Possessions of Britain (pink), New France (blue), and Spain (orange; California, Pacific Northwest, and Great Basin not indicated)It is believed that the first European to explore the east coast of Canada was Norse explorer Leif Erikson.[26][27] In approximately 1000 AD, the Norse built a small short-lived encampment that was occupied sporadically for perhaps 20 years at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.[28] No further European exploration occurred until 1497, when Italian seafarer John Cabot explored and claimed Canada's Atlantic coast in the name of King Henry VII of England.[29] In 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence where, on July 24, he planted a 10-metre (33 ft) cross bearing the words, "long live the King of France", and took possession of the territory New France in the name of King Francis I.[30] The early 16th century saw European mariners with navigational techniques pioneered by the Basque and Portuguese establish seasonal whaling and fishing outposts along the Atlantic coast.[31] In general, early settlements during the Age of Discovery appear to have been short-lived due to a combination of the harsh climate, problems with navigating trade routes and competing outputs in Scandinavia.[32][33]

In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, by the royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I, founded St John's, Newfoundland, as the first North American English seasonal camp.[34] In 1600, the French established their first seasonal trading post at Tadoussac along the Saint Lawrence.[28] French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in 1603 and established the first permanent year-round European settlements at Port Royal (in 1605) and Quebec City (in 1608).[35] Among the colonists of New France, Canadiens extensively settled the Saint Lawrence River valley and Acadians settled the present-day Maritimes, while fur traders and Catholic missionaries explored the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and the Mississippi watershed to Louisiana.[36] The Beaver Wars broke out in the mid-17th century over control of the North American fur trade.[37]

The English established additional settlements in Newfoundland in 1610 along with settlements in the Thirteen Colonies to the south.[38][39] A series of four wars erupted in colonial North America between 1689 and 1763; the later wars of the period constituted the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War.[40] Mainland Nova Scotia came under British rule with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht and Canada and most of New France came under British rule in 1763 after the Seven Years' War.[41]

British North America Benjamin West's The Death of General Wolfe (1771) dramatizes James Wolfe's death during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham at Quebec.

Benjamin West's The Death of General Wolfe (1771) dramatizes James Wolfe's death during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham at Quebec.The Royal Proclamation of 1763 established First Nation treaty rights, created the Province of Quebec out of New France, and annexed Cape Breton Island to Nova Scotia.[42] St John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony in 1769.[43] To avert conflict in Quebec, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act 1774, expanding Quebec's territory to the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.[44] More importantly, the Quebec Act afforded Quebec special autonomy and rights of self-administration at a time when the Thirteen Colonies were increasingly agitating against British rule.[45] It re-established the French language, Catholic faith, and French civil law there, staving off the growth of an independence movement in contrast to the Thirteen Colonies.[46] The Proclamation and the Quebec Act in turn angered many residents of the Thirteen Colonies, further fuelling anti-British sentiment in the years prior to the American Revolution.[42]

After the successful American War of Independence, the 1783 Treaty of Paris recognized the independence of the newly formed United States and set the terms of peace, ceding British North American territories south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River to the new country.[47] The American war of independence also caused a large out-migration of Loyalists, the settlers who had fought against American independence. Many moved to Canada, particularly Atlantic Canada, where their arrival changed the demographic distribution of the existing territories. New Brunswick was in turn split from Nova Scotia as part of a reorganization of Loyalist settlements in the Maritimes, which led to the incorporation of Saint John, New Brunswick, as Canada's first city.[48] To accommodate the influx of English-speaking Loyalists in Central Canada, the Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the province of Canada into French-speaking Lower Canada (later Quebec) and English-speaking Upper Canada (later Ontario), granting each its own elected legislative assembly.[49]

War of 1812 heroine Laura Secord warning British commander James FitzGibbon of an impending American attack at Beaver Dams

War of 1812 heroine Laura Secord warning British commander James FitzGibbon of an impending American attack at Beaver DamsThe Canadas were the main front in the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. Peace came in 1815; no boundaries were changed.[50] Immigration resumed at a higher level, with over 960,000 arrivals from Britain between 1815 and 1850.[51] New arrivals included refugees escaping the Great Irish Famine as well as Gaelic-speaking Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances.[52] Infectious diseases killed between 25 and 33 percent of Europeans who immigrated to Canada before 1891.[8]

The desire for responsible government resulted in the abortive Rebellions of 1837.[53] The Durham Report subsequently recommended responsible government and the assimilation of French Canadians into English culture.[42] The Act of Union 1840 merged the Canadas into a united Province of Canada and responsible government was established for all provinces of British North America east of Lake Superior by 1855.[54] The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending the border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858).[55] The Anglo-Russian Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1825) established the border along the Pacific coast, but, even after the US Alaska Purchase of 1867, disputes continued about the exact demarcation of the Alaska–Yukon and Alaska–BC border.[56]

Confederation and expansion Animated map showing the growth and change of Canada's provinces and territories since Confederation in 1867

Animated map showing the growth and change of Canada's provinces and territories since Confederation in 1867Following three constitutional conferences, the British North America Act, 1867 officially proclaimed Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, initially with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[57][58] Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories, where the Métis' grievances ignited the Red River Rebellion and the creation of the province of Manitoba in July 1870.[59] British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had been united in 1866) joined the confederation in 1871 on the promise of a transcontinental railway extending to Victoria in the province within 10 years,[60] while Prince Edward Island joined in 1873.[61] In 1898, during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, Parliament created the Yukon Territory. Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.[61] Between 1871 and 1896, almost one quarter of the Canadian population emigrated south to the US.[62]

To open the West and encourage European immigration, the Government of Canada sponsored the construction of three transcontinental railways (including the Canadian Pacific Railway), passed the Dominion Lands Act to regulate settlement and established the North-West Mounted Police to assert authority over the territory.[63][64] This period of westward expansion and nation building resulted in the displacement of many Indigenous peoples of the Canadian Prairies to "Indian reserves",[65] clearing the way for ethnic European block settlements.[66] This caused the collapse of the Plains Bison in western Canada and the introduction of European cattle farms and wheat fields dominating the land.[67] The Indigenous peoples saw widespread famine and disease due to the loss of the bison and their traditional hunting lands.[68] The federal government did provide emergency relief, on condition of the Indigenous peoples moving to the reserves.[69] During this time, Canada introduced the Indian Act extending its control over the First Nations to education, government and legal rights.[70]

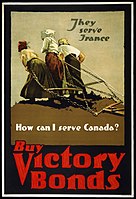

Early 20th century1918 Canadian War bond posters depicting three French women pulling a plow that had been constructed for horses.French version of the poster roughly translates as "They serve France–Everyone can serve; Buy Victory Bonds".The same poster in English, with subtle differences in text. "They serve France—How can I serve Canada? Buy Victory Bonds".Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into the First World War.[71] Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps, which played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major engagements of the war.[72] Out of approximately 625,000 Canadians who served in World War I, some 60,000 were killed and another 172,000 were wounded.[73] The Conscription Crisis of 1917 erupted when the Unionist Cabinet's proposal to augment the military's dwindling number of active members with conscription was met with vehement objections from French-speaking Quebecers.[74] The Military Service Act brought in compulsory military service, though it, coupled with disputes over French language schools outside Quebec, deeply alienated Francophone Canadians and temporarily split the Liberal Party.[74] In 1919, Canada joined the League of Nations independently of Britain,[72] and the Statute of Westminster, 1931, affirmed Canada's independence.[75]

The Great Depression in Canada during the early 1930s saw an economic downturn, leading to hardship across the country.[76] In response to the downturn, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan introduced many elements of a welfare state (as pioneered by Tommy Douglas) in the 1940s and 1950s.[77] On the advice of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, war with Germany was declared effective September 10, 1939, by King George VI, seven days after the United Kingdom. The delay underscored Canada's independence.[72]

The first Canadian Army units arrived in Britain in December 1939. In all, over a million Canadians served in the armed forces during the Second World War and approximately 42,000 were killed and another 55,000 were wounded.[78] Canadian troops played important roles in many key battles of the war, including the failed 1942 Dieppe Raid, the Allied invasion of Italy, the Normandy landings, the Battle of Normandy, and the Battle of the Scheldt in 1944.[72] Canada provided asylum for the Dutch monarchy while that country was occupied and is credited by the Netherlands for major contributions to its liberation from Nazi Germany.[79]

The Canadian economy boomed during the war as its industries manufactured military materiel for Canada, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union.[72] Despite another Conscription Crisis in Quebec in 1944, Canada finished the war with a large army and strong economy.[80]

Contemporary eraThe financial crisis of the Great Depression had led the Dominion of Newfoundland to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a Crown colony ruled by a British governor.[81] After two referendums, Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[82]

Canada's post-war economic growth, combined with the policies of successive Liberal governments, led to the emergence of a new Canadian identity, marked by the adoption of the maple leaf flag in 1965,[83] the implementation of official bilingualism (English and French) in 1969,[84] and the institution of official multiculturalism in 1971.[85] Socially democratic programs were also instituted, such as Medicare, the Canada Pension Plan, and Canada Student Loans; though, provincial governments, particularly Quebec and Alberta, opposed many of these as incursions into their jurisdictions.[86]

A copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

A copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and FreedomsFinally, another series of constitutional conferences resulted in the Canada Act 1982, the patriation of Canada's constitution from the United Kingdom, concurrent with the creation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[87][88][89] Canada had established complete sovereignty as an independent country under its own monarchy.[90][91] In 1999, Nunavut became Canada's third territory after a series of negotiations with the federal government.[92]

At the same time, Quebec underwent profound social and economic changes through the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, giving birth to a secular nationalist movement.[93] The radical Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) ignited the October Crisis with a series of bombings and kidnappings in 1970[94] and the sovereignist Parti Québécois was elected in 1976, organizing an unsuccessful referendum on sovereignty-association in 1980. Attempts to accommodate Quebec nationalism constitutionally through the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990.[95] This led to the formation of the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and the invigoration of the Reform Party of Canada in the West.[96][97] A second referendum followed in 1995, in which sovereignty was rejected by a slimmer margin of 50.6 to 49.4 percent.[98] In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province would be unconstitutional and the Clarity Act was passed by Parliament, outlining the terms of a negotiated departure from Confederation.[95]

In addition to the issues of Quebec sovereignty, a number of crises shook Canadian society in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the explosion of Air India Flight 182 in 1985, the largest mass murder in Canadian history;[99] the École Polytechnique massacre in 1989, a university shooting targeting female students;[100] and the Oka Crisis of 1990,[101] the first of a number of violent confrontations between the government and Indigenous groups.[102] Canada also joined the Gulf War in 1990 as part of a United States–led coalition force and was active in several peacekeeping missions in the 1990s, including the UNPROFOR mission in the former Yugoslavia.[103] Canada sent troops to Afghanistan in 2001 but declined to join the United States–led invasion of Iraq in 2003.[104]

In 2011, Canadian forces participated in the NATO-led intervention into the Libyan Civil War[105] and also became involved in battling the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq in the mid-2010s.[106] The country celebrated its sesquicentennial in 2017, three years before the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada began, on January 27, 2020, with widespread social and economic disruption.[107] In 2021, the possible remains of hundreds of Indigenous people were discovered near the former sites of Canadian Indian residential schools.[108] Administered by the Canadian Catholic Church and funded by the Canadian government from 1828 to 1997, these boarding schools attempted to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.[20]

^ a b Graber, Christoph Beat; Kuprecht, Karolina; Lai, Jessica C. (2012). International Trade in Indigenous Cultural Heritage: Legal and Policy Issues. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-85793-831-2. ^ Dillehay, Thomas D. (2008). The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory. Basic Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7867-2543-4. ^ Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2016). World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-317-34244-1. ^ Rawat, Rajiv (2012). Circumpolar Health Atlas. University of Toronto Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4426-4456-4. ^ Hayes, Derek (2008). Canada: An Illustrated History. Douglas & Mcintyre. pp. 7, 13. ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5. ^ Macklem, Patrick (2001). Indigenous Difference and the Constitution of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8020-4195-1. ^ Sonneborn, Liz (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–12. ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1. ^ a b c Wilson, Donna M; Northcott, Herbert C (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4. ^ Thornton, Russell (2000). "Population history of Native North Americans". In Haines, Michael R; Steckel, Richard Hall (eds.). A population history of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13, 380. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7. ^ O'Donnell, C. Vivian (2008). "Native Populations of Canada". In Bailey, Garrick Alan (ed.). Indians in Contemporary Society. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 2. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8. ^ Marshall, Ingeborg (1998). A History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-7735-1774-5. ^ True Peters, Stephanie (2005). Smallpox in the New World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7614-1637-1. ^ Laidlaw, Z.; Lester, Alan (2015). Indigenous Communities and Settler Colonialism: Land Holding, Loss and Survival in an Interconnected World. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-137-45236-8. ^ Ray, Arthur J. (2005). I Have Lived Here Since The World Began. Key Porter Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-55263-633-6. ^ Preston, David L. (2009). The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667–1783. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7. ^ Miller, J.R. (2009). Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4426-9227-5. ^ Williams, L. (2021). Indigenous Intergenerational Resilience: Confronting Cultural and Ecological Crisis. Routledge Studies in Indigenous Peoples and Policy. Taylor & Francis. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-000-47233-2. ^ Turner, N.J. (2020). Plants, People, and Places: The Roles of Ethnobotany and Ethnoecology in Indigenous Peoples' Land Rights in Canada and Beyond. McGill-Queen's Indigenous and Northern Studies. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-2280-0317-5. ^ Asch, Michael (1997). Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference. UBC Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7748-0581-0. ^ a b Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada (January 1, 2016). Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume I. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–7. ISBN 978-0-7735-9818-8. ^ Lux, M.K. (2016). Separate Beds: A History of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s-1980s. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. University of Toronto Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4426-1386-7. ^ Kirmayer, Laurence J.; Guthrie, Gail Valaskakis (2009). Healing Traditions: The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. UBC Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7748-5863-2. ^ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. 2015. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2016. ^ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada : calls to action.: IR4-8/2015E-PDF - Canada.ca". Government of Canada Publications. July 1, 2002. Retrieved February 20, 2023. ^ "Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples". Ministère de la Justice. July 14, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2023. ^ Wallace, Birgitta (October 12, 2018). "Leif Eriksson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. ^ Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 727–728. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7. ^ a b Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2009). "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27, 82. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3. ^ Blake, Raymond B.; Keshen, Jeffrey; Knowles, Norman J.; Messamore, Barbara J. (2017). Conflict and Compromise: Pre-Confederation Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4426-3553-1. ^ Cartier, Jacques; Biggar, Henry Percival; Cook, Ramsay (1993). The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. University of Toronto Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8020-6000-6. ^ Kerr, Donald Peter (1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: From the beginning to 1800. University of Toronto Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8020-2495-4. ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0. ^ Wynn, Graeme (2007). Canada and Arctic North America: An Environmental History. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-85109-437-0. ^ Rose, George A (October 1, 2007). Cod: The Ecological History of the North Atlantic Fisheries. Breakwater Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-55081-225-1. ^ Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, Michael J. (September 30, 2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7. ^ LaMar, Howard Roberts (1977). The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West. University of Michigan Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-690-00008-5. ^ Tucker, Spencer C; Arnold, James; Wiener, Roberta (September 30, 2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8. ^ Buckner, Phillip Alfred; Reid, John G. (1994). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-8020-6977-1. ^ Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier: spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 978-1-58465-427-8. ^ Nolan, Cathal J (2008). Wars of the age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-313-33046-9. ^ Allaire, Gratien (May 2007). "From 'Nouvelle-France' to 'Francophonie canadienne': a historical survey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2007 (185): 25–52. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.024. S2CID 144657353. ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference buckner was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Hicks, Bruce M (March 2010). "Use of Non-Traditional Evidence: A Case Study Using Heraldry to Examine Competing Theories for Canada's Confederation". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 23 (1): 87–117. doi:10.3828/bjcs.2010.5. ^ Hopkins, John Castell (1898). Canada: an Encyclopaedia of the Country: The Canadian Dominion Considered in Its Historic Relations, Its Natural Resources, its Material Progress and its National Development, by a Corps of Eminent Writers and Specialists. Linscott Publishing Company. p. 125. ^ Nellis, Eric (2010). An Empire of Regions: A Brief History of Colonial British America. University of Toronto Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4426-0403-2. ^ Stuart, Peter; Savage, Allan M. (2011). The Catholic Faith and the Social Construction of Religion: With Particular Attention to the Québec Experience. WestBow Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-1-4497-2084-1. ^ Leahy, Todd; Wilson, Raymond (September 30, 2009). Native American Movements. Scarecrow Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8108-6892-2. ^ Newman, Peter C (2016). Hostages to Fortune: The United Empire Loyalists and the Making of Canada. Touchstone. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4516-8615-9. ^ McNairn, Jeffrey L (2000). The capacity to judge. University of Toronto Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8020-4360-3. ^ Harrison, Trevor; Friesen, John W. (2010). Canadian Society in the Twenty-first Century: An Historical Sociological Approach. Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-1-55130-371-0. ^ Harris, Richard Colebrook; et al. (1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: The land transformed, 1800–1891. University of Toronto Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8020-3447-2. ^ Gallagher, John A. (1936). "The Irish Emigration of 1847 and Its Canadian Consequences". CCHA Report: 43–57. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. ^ Read, Colin (1985). Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7735-8406-8. ^ Romney, Paul (Spring 1989). "From Constitutionalism to Legalism: Trial by Jury, Responsible Government, and the Rule of Law in the Canadian Political Culture". Law and History Review. 7 (1): 121–174. doi:10.2307/743779. JSTOR 743779. S2CID 147047853. ^ Evenden, Leonard J; Turbeville, Daniel E (1992). "The Pacific Coast Borderland and Frontier". In Janelle, Donald G (ed.). Geographical Snapshots of North America. Guilford Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-89862-030-6. ^ Farr, DML; Block, Niko (August 9, 2016). "The Alaska Boundary Dispute". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. ^ Dijkink, Gertjan; Knippenberg, Hans (2001). The Territorial Factor: Political Geography in a Globalising World. Amsterdam University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-90-5629-188-4. ^ Bothwell, Robert (1996). History of Canada Since 1867. Michigan State University Press. pp. 31, 207–310. ISBN 978-0-87013-399-2. ^ Bumsted, JM (1996). The Red River Rebellion. Watson & Dwyer. ISBN 978-0-920486-23-8. ^ "Railway History in Canada | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved March 15, 2021. ^ a b "Building a nation". Canadian Atlas. Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on March 3, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2011. ^ Denison, Merrill (1955). The Barley and the Stream: The Molson Story. McClelland & Stewart Limited. p. 8. ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald". Library and Archives Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011. ^ Cook, Terry (2000). "The Canadian West: An Archival Odyssey through the Records of the Department of the Interior". The Archivist. Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011. ^ Hele, Karl S. (2013). The Nature of Empires and the Empires of Nature: Indigenous Peoples and the Great Lakes Environment. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-55458-422-2. ^ Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914". Canadian Museum of Immigration. Retrieved December 18, 2020. ^ Armitage, Derek; Plummer, Ryan (2010). Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-3-642-12194-4. ^ Daschuk, James William (2013). Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. University of Regina Press. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-0-88977-296-0. ^ Hall, David John (2015). From Treaties to Reserves: The Federal Government and Native Peoples in Territorial Alberta, 1870–1905. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-7735-4595-3. ^ Jackson, Robert J.; Jackson, Doreen; Koop, Royce (2020). Canadian Government and Politics (7th ed.). Broadview Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-4604-0696-0. ^ Tennyson, Brian Douglas (2014). Canada's Great War, 1914–1918: How Canada Helped Save the British Empire and Became a North American Nation. Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8108-8860-9. ^ a b c d e Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). McClelland & Stewart. pp. 130–158, 173, 203–233, 258. ISBN 978-0-7710-6514-9. ^ Granatstein, J. L. (2004). Canada's Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8020-8696-9. ^ a b McGonigal, Richard Morton (1962). "Intro". The Conscription Crisis in Quebec – 1917: a Study in Canadian Dualism. Harvard University Press. ^ Morton, Frederick Lee (2002). Law, Politics and the Judicial Process in Canada. University of Calgary Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-55238-046-8. ^ Bryce, Robert B. (June 1, 1986). Maturing in Hard Times: Canada's Department of Finance through the Great Depression. McGill-Queen's. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7735-0555-1. ^ Mulvale, James P (July 11, 2008). "Basic Income and the Canadian Welfare State: Exploring the Realms of Possibility". Basic Income Studies. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1084. S2CID 154091685. ^ Humphreys, Edward (2013). Great Canadian Battles: Heroism and Courage Through the Years. Arcturus Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-78404-098-7. ^ Goddard, Lance (2005). Canada and the Liberation of the Netherlands. Dundurn Press. pp. 225–232. ISBN 978-1-55002-547-7. ^ Bothwell, Robert (2007). Alliance and illusion: Canada and the world, 1945–1984. UBC Press. pp. 11, 31. ISBN 978-0-7748-1368-6. ^ Alfred Buckner, Phillip (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 135–138. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1. ^ Boyer, J. Patrick (1996). Direct Democracy in Canada: The History and Future of Referendums. Dundurn Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4597-1884-5. ^ Mackey, Eva (2002). The house of difference: cultural politics and national identity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8020-8481-1. ^ Landry, Rodrigue; Forgues, Éric (May 2007). "Official language minorities in Canada: an introduction". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2007 (185): 1–9. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.022. S2CID 143905306. ^ Esses, Victoria M; Gardner, RC (July 1996). "Multiculturalism in Canada: Context and current status". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 28 (3): 145–152. doi:10.1037/h0084934. ^ Sarrouh, Elissar (January 22, 2002). "Social Policies in Canada: A Model for Development" (PDF). Social Policy Series, No. 1. United Nations. pp. 14–16, 22–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2010. ^ "Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982". Government of Canada. May 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017. ^ "A statute worth 75 cheers". The Globe and Mail. March 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. ^ Couture, Christa (January 1, 2017). "Canada is celebrating 150 years of... what, exactly?". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017. ^ Trepanier, Peter (2004). "Some Visual Aspects of the Monarchical Tradition" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017. ^ Bickerton, James; Gagnon, Alain, eds. (2004). Canadian Politics (4th ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 250–254, 344–347. ISBN 978-1-55111-595-5. ^ Légaré, André (2008). "Canada's Experiment with Aboriginal Self-Determination in Nunavut: From Vision to Illusion". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 15 (2–3): 335–367. doi:10.1163/157181108X332659. JSTOR 24674996. ^ Roberts, Lance W.; Clifton, Rodney A.; Ferguson, Barry (2005). Recent Social Trends in Canada, 1960–2000. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-7735-7314-7. ^ Munroe, HD (2009). "The October Crisis Revisited: Counterterrorism as Strategic Choice, Political Result, and Organizational Practice". Terrorism and Political Violence. 21 (2): 288–305. doi:10.1080/09546550902765623. S2CID 143725040. ^ a b Sorens, J (December 2004). "Globalization, secessionism, and autonomy". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 727–752. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.10.003. ^ Leblanc, Daniel (August 13, 2010). "A brief history of the Bloc Québécois". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010. ^ Betz, Hans-Georg; Immerfall, Stefan (1998). The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. St. Martin's Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-312-21134-9. ^ Schmid, Carol L. (2001). The Politics of Language: Conflict, Identity, and Cultural Pluralism in Comparative Perspective: Conflict, Identity, and Cultural Pluralism in Comparative Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-19-803150-5. ^ "Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011. ^ Sourour, Teresa K (1991). "Report of Coroner's Investigation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017. ^ "The Oka Crisis". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011. ^ Roach, Kent (2003). September 11: consequences for Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 15, 59–61, 194. ISBN 978-0-7735-2584-9. ^ Cohen, Lenard J.; Moens, Alexander (1999). "Learning the lessons of UNPROFOR: Canadian peacekeeping in the former Yugoslavia". Canadian Foreign Policy Journal. 6 (2): 85–100. doi:10.1080/11926422.1999.9673175. ^ Jockel, Joseph T; Sokolsky, Joel B (2008). "Canada and the war in Afghanistan: NATO's odd man out steps forward". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 6 (1): 100–115. doi:10.1080/14794010801917212. S2CID 144463530. ^ Hehir, Aidan; Murray, Robert (2013). Libya, the Responsibility to Protect and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-137-27396-3. ^ Juneau, Thomas (2015). "Canada's Policy to Confront the Islamic State". Canadian Global Affairs Institute. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015. ^ "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". Government of Canada. 2021. ^ "Catholic group to release all records from Marievel, Kamloops residential schools". CTVNews. June 25, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- Stay safe

Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer

Royal Canadian Mounted Police officerSafety in Canada is not usually a problem, and some basic common sense will go a long way. Even in the largest cities, violent crime is not a serious problem, and very few people are ever armed. Violent crime needn't worry the average traveller, as it is generally confined to particular neighbourhoods and is rarely a random crime. Overall crime rates in Canadian cities remain low compared to most similar sized urban areas in the United States and much of the rest of the world (though violent crime rates are higher than most western European cities). Crime is higher in overall in western provinces than in Eastern Canada, but is even higher in the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. There have been several high-profile shootings in public/tourist areas; the fact these incidents are so heavily covered by the media is related to the fact that they are considered very rare events.

If you travel near the Canadian-U.S. border, please make sure that you do not accidentally enter the United States in a place where the border is not clearly marked. If you do, you could be subject to lengthy interrogation and possible jail time.

PolicingPolice in Canada are usually hardworking, honest, and trustworthy individuals. If you ever encounter any problems during your stay, even if it's as simple as being lost, approaching a police officer is a good idea.

There are three main types of police forces in Canada: federal, provincial and municipal. The federal police force is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP or "Mounties"), with a widespread presence in all parts of the country other than Quebec, Ontario, and Newfoundland & Labrador, which maintain their own provincial police forces. These are the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), the Sûreté du Québec (SQ) and the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary. All the other provinces and territories (and some rural portions of Newfoundland as well as Labrador) contract their provincial duties to the RCMP.

...Read moreStay safeRead less Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer

Royal Canadian Mounted Police officerSafety in Canada is not usually a problem, and some basic common sense will go a long way. Even in the largest cities, violent crime is not a serious problem, and very few people are ever armed. Violent crime needn't worry the average traveller, as it is generally confined to particular neighbourhoods and is rarely a random crime. Overall crime rates in Canadian cities remain low compared to most similar sized urban areas in the United States and much of the rest of the world (though violent crime rates are higher than most western European cities). Crime is higher in overall in western provinces than in Eastern Canada, but is even higher in the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. There have been several high-profile shootings in public/tourist areas; the fact these incidents are so heavily covered by the media is related to the fact that they are considered very rare events.

If you travel near the Canadian-U.S. border, please make sure that you do not accidentally enter the United States in a place where the border is not clearly marked. If you do, you could be subject to lengthy interrogation and possible jail time.

PolicingPolice in Canada are usually hardworking, honest, and trustworthy individuals. If you ever encounter any problems during your stay, even if it's as simple as being lost, approaching a police officer is a good idea.

There are three main types of police forces in Canada: federal, provincial and municipal. The federal police force is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP or "Mounties"), with a widespread presence in all parts of the country other than Quebec, Ontario, and Newfoundland & Labrador, which maintain their own provincial police forces. These are the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), the Sûreté du Québec (SQ) and the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary. All the other provinces and territories (and some rural portions of Newfoundland as well as Labrador) contract their provincial duties to the RCMP.

In their capacity as a federal police force, RCMP officers typically wear regular police uniforms and drive police cruisers while performing their duties. However, a minority of RCMP officers may appear in their iconic red dress uniform in tourist areas, and for official functions such as parades. Some RCMP officers participate in elaborate ceremonies such as the Musical Ride horse show. While wearing their full dress uniform, their main function is to promote the image of Canada and Canadian Mounties. RCMP officers in full dress are generally not tasked with investigating crime or enforcing the law, although they are still police officers and can perform arrests. In some tourist regions, such as Ottawa, both types of RCMP officers are commonly encountered. This dual-role and dual-appearance of the RCMP, both as federal police, and as a tourist attraction, may create confusion among tourists as to the function of the RCMP. All RCMP officers are police officers, and have a duty to enforce the law.

Cities, towns and regions often have their own police forces, with the Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal forces being three of the largest. Some cities also have special transit police who have full police powers. Some quasi-government agencies, such as universities and power utilities also employ private special police. The Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway each have their own police force. Some First Nations reserves also have their own police force. Canadian Forces Military Police can be found at military bases and other defence-related government facilities.

All three types of police forces can enforce any type of law, be it federal, provincial or municipal. Their jurisdiction overlaps, with the RCMP being able to arrest anywhere in Canada, the OPP and municipal police officers being able to arrest anywhere within their own province. Powers of arrest for Federal, Provincial and municipal police agencies in Canada exist for officers both on, and off duty.

In the national capital region of Ottawa-Gatineau, one can encounter more police jurisdictions than in any other part of Canada. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (both regular uniformed and full dress), the Ontario Provincial Police, the Ottawa police, the Sûreté du Québec, the Gatineau Police, Military Police, and OC Transpo Special Constables, all operate in the region, each with a different style of uniform and police cruiser.

Do not under any circumstances attempt to offer a bribe to a police officer, as this is a crime, and they will enforce laws against it.

TheftIf you are unfortunate enough to get your purse or wallet snatched, the local police will do whatever they can to help. Often, important identification is retrieved after thefts of this sort. In large cities, parked cars are sometimes targeted for opportunistic smash-and-grab thefts, so try to avoid leaving any possessions in open view. Due to the high incidence of such crimes, motorists in Montreal and some other jurisdictions can be fined for leaving their car doors unlocked or for leaving valuables in view. Take a picture of your licence plate and check that your plates are still in place before you go somewhere as some thieves will steal plates to avoid getting pulled over. Auto theft in Montreal, including theft of motor homes and recreational vehicles, may occur in patrolled and overtly secure parking lots and decks. Bike theft can be a common nuisance in metropolitan areas.

Winter storms See also: Cold weather View from behind the wheel in Saskatchewan in the winter

View from behind the wheel in Saskatchewan in the winterCanada is very prone to winter storms (including ice storms and blizzards) from November through March. In Eastern Canada, they are the most likely, but the occasional small one will pop up west of Northwest Ontario usually there it is wind-whipped snow that is the main hazard. Reduce speed, be conscious of other drivers, and pay attention. It's best to carry an emergency kit, in case you have no choice but to spend the night stuck in snow on the highway (yes, this does happen occasionally, especially in more isolated areas). If you are unfamiliar with winter driving and choose to visit Canada during the winter months, consider using another mode of transportation to travel within the country. While the vast majority of winter weather occurs during the winter months, some parts of Canada such as the Prairies, Labrador, Northern Canada, and mountain regions may experience severe, if brief, winter-like conditions at any time during the year.

If you are touring on foot, it is best to bundle up as much as possible in layers with heavy socks, thermal underwear and gloves; winter storms can bring with them extreme winds alongside frigid temperatures and frostbite can occur in a matter of minutes.

Firearms and weaponsUnlike the US, Canada has no constitutional rights relating to gun ownership. Possession, purchase, and use of any firearms requires proper licences for the weapons and the user, and is subject to federal laws. Firearms are classed (mainly based on barrel length) as non-restricted (subject to the least amount of training and licensing), restricted (more licensing and training required) and prohibited (not legally available). Most rifles and shotguns are non-restricted, as they are used extensively for hunting, on farms, or for protection in remote areas. Handguns or pistols are restricted weapons, but may be obtained and used legally with the proper licences.

Generally the only people who carry handguns are Police, Border Services Officers, Wildlife Officers in most provinces, private security guards who transport money, people who work in remote "wilderness" areas who are properly licensed, and sport shooters who specialize in pistol shooting.

As a general rule, you are not allowed to carry guns for self-defence in Canada. It is possible to import non-prohibited firearms such as most types of rifle and shotgun for sporting purposes like target shooting and hunting, and non-prohibited handguns for target shooting may also be imported with the correct paperwork.

All firearms must be declared to customs on entry into Canada, even if unrestricted, and failing to do so is a criminal offence punishable by fines and imprisonment. Prohibited firearms, such as military-grade assault rifles, will be seized at customs and destroyed. Air soft guns that are replica firearms are prohibited. Travellers should check with the Canada Firearms Centre and the Canada Border Services Agency before importing firearms of any type before arrival.

Switchblades, butterfly knives, spring loaded blades and any other knife that opens automatically are classified as Prohibited and are illegal in Canada, as are Nunchucks, Tasers and other electric stun guns, most devices concealing knives, such as belt buckle knives and knife combs, and articles of clothing or jewellery designed to be used as weapons. Mace and pepper spray are also illegal unless sold specifically for use against animals.

Cannabis and other drugs Note: Under no circumstances should you attempt to bring any amount of any controlled substance into or out of Canada. This includes marijuana, even though it is legal to use marijuana in Canada. It is also illegal to take marijuana from Canada to any U.S. state where marijuana is legal and vice versa, including bordering states such as Alaska, Washington, and Vermont. Penalties in Canada for drug smuggling (into or out of the country) can be severe, with life sentences possible.

Note: Under no circumstances should you attempt to bring any amount of any controlled substance into or out of Canada. This includes marijuana, even though it is legal to use marijuana in Canada. It is also illegal to take marijuana from Canada to any U.S. state where marijuana is legal and vice versa, including bordering states such as Alaska, Washington, and Vermont. Penalties in Canada for drug smuggling (into or out of the country) can be severe, with life sentences possible.

Canada (Information last updated Mar 2020)Marijuana use is legal in Canada since October 17, 2018, and every adult is allowed to possess up to 30 grams (1 ounce) of dried marijuana at a time. Each province has licensed some retail stores to carry cannabis products or has provided them for order over the internet. It remains illegal to buy cannabis from anyone other than a licensed shop; the punishment is theoretically jail time and although it is rarely prosecuted it could easily lead a foreigner to be deported. For advice on where to get legal weed in Canada, see the Wikivoyage guide of the province or cities you will be visiting. Cities also generally have "smoking bylaws" that restrict where one can legally smoke tobacco and these also apply to marijuana. The punishment for breaking these bylaws is generally a large fine, but not jail time. Private businesses are also allowed to prohibit smoking on their property, and many hotels would not take kindly to the smell of weed in their rooms. The law on providing marijuana to minors remains extremely strict, and would certainly result in deportation or jail time if convicted.

Driving while impaired by drugs (including marijuana and even legal "drowsy" drugs) is a criminal code offence and is treated in the same way as driving under the influence of alcohol, with severe penalties. Do not attempt to drive while high; visitors can expect to be deported after serving jail time or paying very large fines.

Khat is illegal in Canada, and will get you arrested and deported if you try to pack it in your luggage and get caught by customs.

Drunk driving Ontario Highway 401

Ontario Highway 401Canadians take drunk driving very seriously, and it is a social taboo in most circles to drink and drive. Driving while under the influence of alcohol or marijuana is also punishable under the Criminal Code of Canada and can involve jail time, particularly for repeat offences. If you "blow over" the legal limit of blood alcohol content (BAC) on a roadside Breathalyzer machine test, you will be arrested and spend at least a few hours in jail. Being convicted for driving under the influence (DUI) will almost certainly mean the end of your trip to Canada, a criminal record and you being barred from re-entering Canada for at least 5 years. 80 mg of alcohol per 100ml of blood (0.08%) is the legal limit for a criminal conviction. Many jurisdictions call for fines, licence suspension and vehicle impoundment at 40 mg of alcohol per 100 ml of blood (0.04%), or if the officer reasonably believes you are too intoxicated to drive. While having a BAC of 0.03% when tested at a police checkpoint ('Checkstop' or 'ride-stop', which is designed to catch drunk drivers) will not result in arrest, having the same BAC after being pulled over for driving erratically, or after getting involved in an accident may result in being charged with DUI.

Those crossing the land border into Canada from the USA while driving under the influence will get arrested by the Border Services Officers.

Refusing a breathalyzer test is also a Criminal Code offence, and will result in the same penalties as had you blown over. If a police officer demands that you supply a breath sample, your best option is to take your chances with the machine.

Hate speech and discriminationCanada is a very multicultural society, and the vast majority of Canadians are open minded and accepting. Thus, it is unlikely to meet ridicule on the basis of race, gender, religion or sexual orientation — while this does happen on occasion, it's rare enough that such ridicule is aired as a local news story even in the largest cities.

Hate speech — communication that may incite violence toward an identifiable group — is illegal in Canada and can lead to prosecution, jail time, and deportation. Similarly, Canadian law also prohibits any form of discrimination in education and employment.