Bosnia and Herzegovina

Context of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Serbo-Croatian: Bosna i Hercegovina / Босна и Херцеговина, pronounced [bôsna i xěrtseɡoʋina]), abbreviated BiH (БиХ) or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeastern Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and Herzegovina borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to the north and southwest. In the south it has a narrow coast on the Adriatic Sea within the Mediterranean, which is about 20 kilometres (12 miles) long...Read more

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Serbo-Croatian: Bosna i Hercegovina / Босна и Херцеговина, pronounced [bôsna i xěrtseɡoʋina]), abbreviated BiH (БиХ) or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeastern Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and Herzegovina borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to the north and southwest. In the south it has a narrow coast on the Adriatic Sea within the Mediterranean, which is about 20 kilometres (12 miles) long and surrounds the town of Neum. Bosnia, which is the inland region of the country, has a moderate continental climate with hot summers and cold, snowy winters. In the central and eastern regions of the country, the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and in the northeast it is predominantly flat. Herzegovina, which is the smaller, southern region of the country, has a Mediterranean climate and is mostly mountainous. Sarajevo is the capital and the largest city of the country followed by Banja Luka, Tuzla and Zenica.

The area that is now Bosnia and Herzegovina has been inhabited by humans since at least the Upper Paleolithic, but evidence suggests that during the Neolithic age, permanent human settlements were established, including those that belonged to the Butmir, Kakanj, and Vučedol cultures. After the arrival of the first Indo-Europeans, the area was populated by several Illyrian and Celtic civilizations. Culturally, politically, and socially, the country has a rich and complex history. The ancestors of the South Slavic peoples that populate the area today arrived during the 6th through the 9th century. In the 12th century, the Banate of Bosnia was established; by the 14th century, this had evolved into the Kingdom of Bosnia. In the mid-15th century, it was annexed into the Ottoman Empire, under whose rule it remained until the late 19th century. The Ottomans brought Islam to the region, and altered much of the country's cultural and social outlook.

From the late 19th century until World War I, the country was annexed into the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In the interwar period, Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. After World War II, it was granted full republic status in the newly formed Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1992, following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the republic proclaimed independence. This was followed by the Bosnian War, which lasted until late 1995 and was brought to a close with the signing of the Dayton Agreement.

Today, the country is home to three main ethnic groups, designated "constituent peoples" in the country's constitution. The Bosniaks are the largest group of the three, the Serbs are the second-largest, and the Croats are the third-largest. In English, all natives of Bosnia and Herzegovina, regardless of ethnicity, are called Bosnian. Minorities, who under the constitution are categorized as "others", include Jews, Roma, Albanians, Montenegrins, Ukrainians and Turks.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a bicameral legislature and a three-member presidency made up of one member from each of the three major ethnic groups. However, the central government's power is highly limited, as the country is largely decentralized. It comprises two autonomous entities—the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska—and a third unit, the Brčko District, which is governed by its own local government. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina furthermore consists of 10 cantons.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a developing country and ranks 74th in the Human Development Index. Its economy is dominated by industry and agriculture, followed by tourism and the service sector. Tourism has increased significantly in recent years. The country has a social-security and universal-healthcare system, and primary and secondary level education is free. It is a member of the UN, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Council of Europe, the Partnership for Peace, and the Central European Free Trade Agreement; it is also a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean, established in July 2008. Bosnia and Herzegovina is an EU candidate country and has also been a candidate for NATO membership since April 2010, when it received a Membership Action Plan.

More about Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Currency Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark

- Calling code +387

- Internet domain .ba

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 4.84

- Population 3816459

- Area 51197

- Driving side right

Iron Age cult carriage from Banjani, near Sokolac

Iron Age cult carriage from Banjani, near Sokolac Read moreRead less

Read moreRead less Iron Age cult carriage from Banjani, near SokolacEarly history

Iron Age cult carriage from Banjani, near SokolacEarly history Mogorjelo, ancient Roman suburban Villa Rustica from the 4th century, near Čapljina

Mogorjelo, ancient Roman suburban Villa Rustica from the 4th century, near ČapljinaBosnia has been inhabited by humans since at least the Paleolithic, as one of the oldest cave paintings was found in Badanj cave. Major Neolithic cultures such as the Butmir and Kakanj were present along the river Bosna dated from c. 6230 BCE–c. 4900 BCE.

The bronze culture of the Illyrians, an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form, started to organize itself in today's Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo,[a] Montenegro and Albania.

From 8th century BCE, Illyrian tribes evolved into kingdoms. The earliest recorded kingdom in Illyria (a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians, as recorded in classical antiquity) was the Enchele in the 8th century BCE. The era in which we observe other Illyrian kingdoms begins approximately at 400 BCE and ends at 167 BCE. The Autariatae under Pleurias (337 BCE) were considered to have been a kingdom. The Kingdom of the Ardiaei (originally a tribe from the Neretva valley region) began at 230 BCE and ended at 167 BCE. The most notable Illyrian kingdoms and dynasties were those of Bardylis of the Dardani and of Agron of the Ardiaei who created the last and best-known Illyrian kingdom. Agron ruled over the Ardiaei and had extended his rule to other tribes as well.

From the 7th century BCE, bronze was replaced by iron, after which only jewelry and art objects were still made out of bronze. Illyrian tribes, under the influence of Hallstatt cultures to the north, formed regional centers that were slightly different. Parts of Central Bosnia were inhabited by the Daesitiates tribe, most commonly associated with the Central Bosnian cultural group. The Iron Age Glasinac-Mati culture is associated with the Autariatae tribe.

A very important role in their life was the cult of the dead, which is seen in their careful burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of their burial sites. In northern parts, there was a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the south the dead were buried in large stone or earth tumuli (natively called gromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 m wide and 5 m high. Japodian tribes had an affinity to decoration (heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze foil).

In the 4th century BCE, the first invasion of Celts is recorded. They brought the technique of the pottery wheel, new types of fibulas and different bronze and iron belts. They only passed on their way to Greece, so their influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina is negligible. Celtic migrations displaced many Illyrian tribes from their former lands, but some Celtic and Illyrian tribes mixed. Concrete historical evidence for this period is scarce, but overall it appears the region was populated by a number of different peoples speaking distinct languages.

In the Neretva Delta in the south, there were important Hellenistic influences of the Illyrian Daors tribe. Their capital was Daorson in Ošanići near Stolac. Daorson, in the 4th century BCE, was surrounded by megalithic, 5 m high stonewalls (as large as those of Mycenae in Greece), composed of large trapezoid stone blocks. Daors made unique bronze coins and sculptures.

Conflict between the Illyrians and Romans started in 229 BCE, but Rome did not complete its annexation of the region until AD 9. It was precisely in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina that Rome fought one of the most difficult battles in its history since the Punic Wars, as described by the Roman historian Suetonius.[1] This was the Roman campaign against Illyricum, known as Bellum Batonianum.[2] The conflict arose after an attempt to recruit Illyrians, and a revolt spanned for four years (6–9 AD), after which they were subdued.[3] In the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from the entire Roman Empire settled among the Illyrians, and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.[4]

Following the split of the Empire between 337 and 395 AD, Dalmatia and Pannonia became parts of the Western Roman Empire. The region was conquered by the Ostrogoths in 455 AD. It subsequently changed hands between the Alans and the Huns. By the 6th century, Emperor Justinian I had reconquered the area for the Byzantine Empire. Slavs overwhelmed the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries. Illyrian cultural traits were adopted by the South Slavs, as evidenced in certain customs and traditions, placenames, etc.[5]

Middle Ages Hval's Codex, illustrated Slavic manuscript from medieval Bosnia

Hval's Codex, illustrated Slavic manuscript from medieval BosniaThe Early Slavs raided the Western Balkans, including Bosnia, in the 6th and early 7th century (amid the Migration Period), and were composed of small tribal units drawn from a single Slavic confederation known to the Byzantines as the Sclaveni (whilst the related Antes, roughly speaking, colonized the eastern portions of the Balkans).[6][7] Tribes recorded by the ethnonyms of "Serb" and "Croat" are described as a second, latter, migration of different people during the second quarter of the 7th century who could or could not have been particularly numerous;[6][8][9] these early "Serb" and "Croat" tribes, whose exact identity is subject to scholarly debate,[9] came to predominate over the Slavs in the neighbouring regions. According to Emperor Constantine VII, Croats settled western Bosnia, and Serbs the Trebinje and Zahumlje area; the rest of Bosnia was apparently between Serb and Croat rule.[10][11]

Bosnia is also believed to be first mentioned as a land (horion Bosona) in Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus' De Administrando Imperio in the mid 10th century, at the end of a chapter (Chap. 32) entitled Of the Serbs and the country in which they now dwell.[12] This has been scholarly interpreted in several ways and used especially by the Serb national ideologists to prove Bosnia as originally a "Serb" land.[12] Other scholars have asserted the inclusion of Bosnia into Chapter 32 to merely be the result of Serbian Grand Duke Časlav's temporary rule over Bosnia at the time, while also pointing out Porphyrogenitus does not say anywhere explicitly that Bosnia is a "Serb land".[13] In fact, the very translation of the critical sentence where the word Bosona (Bosnia) appears is subject to varying interpretation.[12] In time, Bosnia formed a unit under its own ruler, who called himself Bosnian.[14] Bosnia, along with other territories, became part of Duklja in the 11th century, although it retained its own nobility and institutions.[15]

Bosnia in the Middle Ages spanning the Banate of Bosnia and the succeeding Kingdom of Bosnia

Bosnia in the Middle Ages spanning the Banate of Bosnia and the succeeding Kingdom of BosniaIn the High Middle Ages, political circumstance led to the area being contested between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Byzantine Empire. Following another shift of power between the two in the early 12th century, Bosnia found itself outside the control of both and emerged as the Banate of Bosnia (under the rule of local bans).[4][16] The first Bosnian ban known by name was Ban Borić.[17] The second was Ban Kulin, whose rule marked the start of a controversy involving the Bosnian Church – considered heretical by the Roman Catholic Church. In response to Hungarian attempts to use church politics regarding the issue as a way to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders to renounce the heresy and embraced Catholicism in 1203. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions remained unchanged long after Kulin's death in 1204, waning only after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254. During this time, the population was called Dobri Bošnjani ("Good Bosnians").[18][19] The names Serb and Croat, though occasionally appearing in peripheral areas, were not used in Bosnia proper.[20]

Bosnian history from then until the early 14th century was marked by a power struggle between the Šubić and Kotromanić families. This conflict came to an end in 1322, when Stephen II Kotromanić became Ban. By the time of his death in 1353, he was successful in annexing territories to the north and west, as well as Zahumlje and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his ambitious nephew Tvrtko who, following a prolonged struggle with nobility and inter-family strife, gained full control of the country in 1367. By the year 1377, Bosnia was elevated into a kingdom with the coronation of Tvrtko as the first Bosnian King in Mile near Visoko in the Bosnian heartland.[21][22][23]

Following his death in 1391 however, Bosnia fell into a long period of decline. The Ottoman Empire had started its conquest of Europe and posed a major threat to the Balkans throughout the first half of the 15th century. Finally, after decades of political and social instability, the Kingdom of Bosnia ceased to exist in 1463 after its conquest by the Ottoman Empire.[24]

There was a general awareness in medieval Bosnia, at least amongst the nobles, that they shared a join state with Serbia and that they belonged to the same ethnic group. That awareness diminished over time, due to differences in political and social development, but it was kept in Herzegovina and parts of Bosnia which were a part of Serbian state.[25]

Ottoman Empire Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque in Sarajevo, dating from 1531

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque in Sarajevo, dating from 1531The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.[26]

Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.[4]

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous Bosnian Church disappeared altogether (ostensibly by conversion of its members to Islam). The Ottomans referred to them as kristianlar while the Orthodox and Catholics were called gebir or kafir, meaning "unbeliever".[27] The Bosnian Franciscans (and the Catholic population as a whole) were protected by official imperial decrees and in accordance and full extent of Ottoman laws; however, in effect, these often merely affected arbitrary rule and behavior of powerful local elite.[4]

As the Ottoman Empire continued their rule in the Balkans (Rumelia), Bosnia was somewhat relieved of the pressures of being a frontier province, and experienced a period of general welfare. A number of cities, such as Sarajevo and Mostar, were established and grew into regional centers of trade and urban culture and were then visited by Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi in 1648. Within these cities, various Ottoman Sultans financed the construction of many works of Bosnian architecture such as the country's first library in Sarajevo, madrassas, a school of Sufi philosophy, and a clock tower (Sahat Kula), bridges such as the Stari Most, the Emperor's Mosque and the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque.[28]

Furthermore, several Bosnian Muslims played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural and political history during this time.[29] Bosnian recruits formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles of Mohács and Krbava field, while numerous other Bosnians rose through the ranks of the Ottoman military to occupy the highest positions of power in the Empire, including admirals such as Matrakçı Nasuh; generals such as Isa-Beg Ishaković, Gazi Husrev-beg, Telli Hasan Pasha and Sarı Süleyman Pasha; administrators such as Ferhad Pasha Sokolović and Osman Gradaščević; and Grand Viziers such as the influential Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and Damat Ibrahim Pasha. Some Bosnians emerged as Sufi mystics, scholars such as Muhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi, Ali Džabić; and poets in the Turkish, Albanian, Arabic, and Persian languages.[30]

Austro-Hungarian troops enter Sarajevo, 1878

Austro-Hungarian troops enter Sarajevo, 1878However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of the Great Turkish War with the treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 again made Bosnia the Empire's westernmost province. The 18th century was marked by further military failures, numerous revolts within Bosnia, and several outbreaks of plague.[31]

The Porte's efforts at modernizing the Ottoman state were met with distrust growing to hostility in Bosnia, where local aristocrats stood to lose much through the proposed Tanzimat reforms. This, combined with frustrations over territorial, political concessions in the north-east, and the plight of Slavic Muslim refugees arriving from the Sanjak of Smederevo into Bosnia Eyalet, culminated in a partially unsuccessful revolt by Husein Gradaščević, who endorsed a Bosnia Eyalet autonomous from the authoritarian rule of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II, who persecuted, executed and abolished the Janissaries and reduced the role of autonomous Pashas in Rumelia. Mahmud II sent his Grand vizier to subdue Bosnia Eyalet and succeeded only with the reluctant assistance of Ali Pasha Rizvanbegović.[30] Related rebellions were extinguished by 1850, but the situation continued to deteriorate.

New nationalist movements appeared in Bosnia by the middle of the 19th century. Shortly after Serbia's breakaway from the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, Serbian and Croatian nationalism rose up in Bosnia, and such nationalists made irredentist claims to Bosnia's territory. This trend continued to grow in the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries.[32]

Agrarian unrest eventually sparked the Herzegovinian rebellion, a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, a situation that led to the Congress of Berlin and the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.[4]

Austria-HungaryAt the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy obtained the occupation and administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and he also obtained the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which would remain under Ottoman administration until 1908, when the Austro-Hungarian troops withdrew from the Sanjak.

Although Austro-Hungarian officials quickly came to an agreement with the Bosnians, tensions remained and a mass emigration of Bosnians occurred.[4] However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms they intended would make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model" colony.

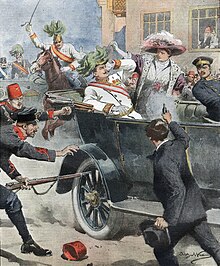

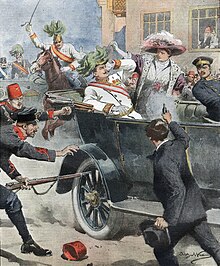

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in Sarajevo, by Gavrilo Princip

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in Sarajevo, by Gavrilo PrincipHabsburg rule had several key concerns in Bosnia. It tried to dissipate the South Slav nationalism by disputing the earlier Serb and Croat claims to Bosnia and encouraging identification of Bosnian or Bosniak identity.[33] Habsburg rule also tried to provide for modernisation by codifying laws, introducing new political institutions, establishing and expanding industries.[34]

Austria–Hungary began to plan the annexation of Bosnia, but due to international disputes the issue was not resolved until the annexation crisis of 1908.[35] Several external matters affected the status of Bosnia and its relationship with Austria–Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia in 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade.[36] Then in 1908, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns that the Istanbul government might seek the outright return of Bosnia and Herzegovina. These factors caused the Austro-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution of the Bosnian question sooner, rather than later.

Taking advantage of turmoil in the Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian diplomacy tried to obtain provisional Russian approval for changes over the status of Bosnia and Herzegovina and published the annexation proclamation on 6 October 1908.[37] Despite international objections to the Austro-Hungarian annexation, Russians and their client state, Serbia, were compelled to accept the Austrian-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in March 1909.

In 1910, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph proclaimed the first constitution in Bosnia, which led to relaxation of earlier laws, elections and formation of the Bosnian parliament and growth of new political life.[38]

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb member of the revolutionary movement Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo—an event that was the spark that set off World War I. At the end of the war, the Bosniaks had lost more men per capita than any other ethnic group in the Habsburg Empire whilst serving in the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry (known as Bosniaken) of the Austro-Hungarian Army.[39] Nonetheless, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.[29]

The Austro-Hungarian authorities established an auxiliary militia known as the Schutzkorps with a moot role in the empire's policy of anti-Serb repression.[40] Schutzkorps, predominantly recruited among the Muslim (Bosniak) population, were tasked with hunting down rebel Serbs (the Chetniks and Komitadji)[41] and became known for their persecution of Serbs particularly in Serb populated areas of eastern Bosnia, where they partly retaliated against Serbian Chetniks who in fall 1914 had carried out attacks against the Muslim population in the area.[42][43] The proceedings of the Austro-Hungarian authorities led to around 5,500 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina being arrested, and between 700 and 2,200 died in prison while 460 were executed.[41] Around 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[41]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia "Keep/Protect Yugoslavia" (Čuvajte Jugoslaviju), a variant of the alleged last words of King Alexander I, in an illustration of Yugoslav peoples dancing the kolo

"Keep/Protect Yugoslavia" (Čuvajte Jugoslaviju), a variant of the alleged last words of King Alexander I, in an illustration of Yugoslav peoples dancing the koloFollowing World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the South Slav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (soon renamed Yugoslavia). Political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina at this time was marked by two major trends: social and economic unrest over property redistribution and the formation of several political parties that frequently changed coalitions and alliances with parties in other Yugoslav regions.[29]

The dominant ideological conflict of the Yugoslav state, between Croatian regionalism and Serbian centralization, was approached differently by Bosnia and Herzegovina's major ethnic groups and was dependent on the overall political atmosphere.[4] The political reforms brought about in the newly established Yugoslavian kingdom saw few benefits for the Bosnian Muslims; according to the 1910 final census of land ownership and population according to religious affiliation conducted in Austria-Hungary, Muslims owned 91.1%, Orthodox Serbs owned 6.0%, Croat Catholics owned 2.6% and others, 0.3% of the property. Following the reforms, Bosnian Muslims were dispossessed of a total of 1,175,305 hectares of agricultural and forest land.[44]

Although the initial split of the country into 33 oblasts erased the presence of traditional geographic entities from the map, the efforts of Bosnian politicians, such as Mehmed Spaho, ensured the six oblasts carved up from Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponded to the six sanjaks from Ottoman times and, thus, matched the country's traditional boundary as a whole.[4]

The establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, however, brought the redrawing of administrative regions into banates or banovinas that purposely avoided all historical and ethnic lines, removing any trace of a Bosnian entity.[4] Serbo-Croat tensions over the structuring of the Yugoslav state continued, with the concept of a separate Bosnian division receiving little or no consideration.

The Cvetković-Maček Agreement that created the Croatian banate in 1939 encouraged what was essentially a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croatia and Serbia.[30] However the rising threat of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany forced Yugoslav politicians to shift their attention. Following a period that saw attempts at appeasement, the signing of the Tripartite Treaty, and a coup d'état, Yugoslavia was finally invaded by Germany on 6 April 1941.[4]

World War II (1941–45) The railway bridge over the Neretva River in Jablanica, twice destroyed during the 1943 Case White offensive

The railway bridge over the Neretva River in Jablanica, twice destroyed during the 1943 Case White offensiveOnce the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by German forces in World War II, all of Bosnia and Herzegovina was ceded to the Nazi puppet regime, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) led by the Ustaše. The NDH leaders embarked on a campaign of extermination of Serbs, Jews, Romani as well as dissident Croats, and, later, Josip Broz Tito's Partisans by setting up a number of death camps.[45] The regime systematically and brutally massacred Serbs in villages in the countryside, using a variety of tools.[46] The scale of the violence meant that approximately every sixth Serb living in Bosnia and Herzegovina was the victim of a massacre and virtually every Serb had a family member that was killed in the war, mostly by the Ustaše. The experience had a profound impact in the collective memory of Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[47] An estimated 209,000 Serbs or 16.9% of its Bosnia population were killed on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war.[48]

The Ustaše recognized both Catholicism and Islam as the national religions, but held the position Eastern Orthodox Church, as a symbol of Serb identity, was their greatest foe.[49] Although Croats were by far the largest ethnic group to constitute the Ustaše, the Vice President of the NDH and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization Džafer Kulenović was a Muslim, and Muslims in total constituted nearly 12% of the Ustaše military and civil service authority.[50]

Many Serbs themselves took up arms and joined the Chetniks, a Serb nationalist movement with the aim of establishing an ethnically homogeneous 'Greater Serbian' state[51] within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Chetniks, in turn, pursued a genocidal campaign against ethnic Muslims and Croats, as well as persecuting a large number of communist Serbs and other Communist sympathizers, with the Muslim populations of Bosnia, Herzegovina and Sandžak being a primary target.[52] Once captured, Muslim villagers were systematically massacred by the Chetniks.[53] Of the 75,000 Muslims who died in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war,[54] approximately 30,000 (mostly civilians) were killed by the Chetniks.[55] Massacres against Croats were smaller in scale but similar in action.[56] Between 64,000 and 79,000 Bosnian Croats were killed between April 1941 to May 1945.[54] Of these, about 18,000 were killed by the Chetniks.[55]

Eternal flame memorial to military and civilian World War II victims in SarajevoA percentage of Muslims served in Nazi Waffen-SS units.[57] These units were responsible for massacres of Serbs in northwest and eastern Bosnia, most notably in Vlasenica.[58] On 12 October 1941, a group of 108 prominent Sarajevan Muslims signed the Resolution of Sarajevo Muslims by which they condemned the persecution of Serbs organized by the Ustaše, made distinction between Muslims who participated in such persecutions and the Muslim population as a whole, presented information about the persecutions of Muslims by Serbs, and requested security for all citizens of the country, regardless of their identity.[59]

Starting in 1941, Yugoslav communists under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito organized their own multi-ethnic resistance group, the Partisans, who fought against both Axis and Chetnik forces. On 29 November 1943, the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) with Tito at its helm held a founding conference in Jajce where Bosnia and Herzegovina was reestablished as a republic within the Yugoslavian federation in its Habsburg borders.[60] During the entire course of World War II in Yugoslavia, 64.1% of all Bosnian Partisans were Serbs, 23% were Muslims and 8.8% Croats.[61]

Military success eventually prompted the Allies to support the Partisans, resulting in the successful Maclean Mission, but Tito declined their offer to help and relied on his own forces instead. All the major military offensives by the antifascist movement of Yugoslavia against Nazis and their local supporters were conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina and its peoples bore the brunt of the fighting. More than 300,000 people died in Bosnia and Herzegovina in World War II.[62] At the end of the war, the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, with the constitution of 1946, officially made Bosnia and Herzegovina one of six constituent republics in the new state.[4]

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992) Bosnia and Herzegovina's flag while part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Bosnia and Herzegovina's flag while part of the Socialist Federal Republic of YugoslaviaDue to its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor in the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[4] However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was relatively peaceful and very prosperous, with high employment, a strong industrial and export oriented economy, a good education system and social and medical security for every citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Several international corporations operated in Bosnia — Volkswagen as part of TAS (car factory in Sarajevo, from 1972), Coca-Cola (from 1975), SKF Sweden (from 1967), Marlboro, (a tobacco factory in Sarajevo), and Holiday Inn hotels. Sarajevo was the site of the 1984 Winter Olympics.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Bosnia was a political backwater of Yugoslavia. In the 1970s, a strong Bosnian political elite arose, fueled in part by Tito's leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement and Bosnians serving in Yugoslavia's diplomatic corps. While working within the Socialist system, politicians such as Džemal Bijedić, Branko Mikulić and Hamdija Pozderac reinforced and protected the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[63] Their efforts proved key during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980, and are today considered some of the early steps towards Bosnian independence. However, the republic did not escape the increasingly nationalistic climate of the time. With the fall of communism and the start of the breakup of Yugoslavia, doctrine of tolerance began to lose its potency, creating an opportunity for nationalist elements in the society to spread their influence.[64]

Bosnian War (1992–1995) Dissolution of Yugoslavia

Dissolution of YugoslaviaOn 18 November 1990, multi-party parliamentary elections were held throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. A second round followed on 25 November, resulting in a national assembly where communist power was replaced by a coalition of three ethnically based parties.[65] Following Slovenia and Croatia's declarations of independence from Yugoslavia, a significant split developed among the residents of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the issue of whether to remain within Yugoslavia (overwhelmingly favored by Serbs) or seek independence (overwhelmingly favored by Bosniaks and Croats).[66]

The Serb members of parliament, consisting mainly of the Serb Democratic Party members, abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo, and formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 24 October 1991, which marked the end of the three-ethnic coalition that governed after the elections in 1990. This Assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992. It was renamed Republika Srpska in August 1992. On 18 November 1991, the party branch in Bosnia and Herzegovina of the ruling party in the Republic of Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), proclaimed the existence of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia in a separate part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) as its military branch.[67] It went unrecognized by the Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which declared it illegal.[68][69]

The Executive Council Building burns after being struck by tank fire during the siege of Sarajevo, 1992

The Executive Council Building burns after being struck by tank fire during the siege of Sarajevo, 1992A declaration of the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 15 October 1991 was followed by a referendum for independence on 29 February and 1 March 1992, which was boycotted by the great majority of Serbs. The turnout in the independence referendum was 63.4 percent and 99.7 percent of voters voted for independence.[70] Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on 6 April 1992.[71] The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was admitted as a member state of the United Nations on 22 May 1992.[72] Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević and Croatian leader Franjo Tuđman are believed to have agreed on a partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina in March 1991, with the aim of establishing Greater Serbia and Greater Croatia.[73]

Following Bosnia and Herzegovina's declaration of independence, Bosnian Serb militias mobilized in different parts of the country. Government forces were poorly equipped and unprepared for the war.[74] International recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina increased diplomatic pressure for the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) to withdraw from the republic's territory, which they officially did in June 1992. The Bosnian Serb members of the JNA simply changed insignia, formed the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), and continued fighting. Armed and equipped from JNA stockpiles in Bosnia, supported by volunteers and various paramilitary forces from Serbia, and receiving extensive humanitarian, logistical and financial support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Republika Srpska's offensives in 1992 managed to place much of the country under its control.[4] The Bosnian Serb advance was accompanied by the ethnic cleansing of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats from VRS-controlled areas. Dozens of concentration camps were established in which inmates were subjected to violence and abuse, including rape.[75] The ethnic cleansing culminated in the Srebrenica massacre of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in July 1995, which was ruled to have been a genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).[76] Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces also committed war crimes against civilians from different ethnic groups, though on a smaller scale.[77][78][79][80] Most of the Bosniak and Croat atrocities were committed during the Croat–Bosniak War, a sub-conflict of the Bosnian War that pitted the Army of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) against the HVO. The Bosniak-Croat conflict ended in March 1994, with the signing of the Washington Agreement, leading to the creation of a joint Bosniak-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which amalgamated HVO-held territory with that held by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH).[81]

Recent history Tuzla government building burning after anti-government clashes on 7 February 2014

Tuzla government building burning after anti-government clashes on 7 February 2014On 4 February 2014, the protests against the Government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the country's two entities, dubbed the Bosnian Spring, the name being taken from the Arab Spring, began in the northern town of Tuzla. Workers from several factories that had been privatised and gone bankrupt assembled to demand action over jobs, unpaid salaries and pensions.[82] Soon protests spread to the rest of the Federation, with violent clashes reported in close to 20 towns, the biggest of which were Sarajevo, Zenica, Mostar, Bihać, Brčko and Tuzla.[83] The Bosnian news media reported that hundreds of people had been injured during the protests, including dozens of police officers, with bursts of violence in Sarajevo, in the northern city of Tuzla, in Mostar in the south, and in Zenica in central Bosnia. The same level of unrest or activism did not occur in Republika Srpska, but hundreds of people also gathered in support of protests in the city of Banja Luka against its separate government.[84][85][86]

The protests marked the largest outbreak of public anger over high unemployment and two decades of political inertia in the country since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995.[87]

According to a report made by Christian Schmidt of the Office of High Representative in late 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina has been experiencing intensified political and ethnic tensions, which could potentially break the country apart and slide it back into war once again.[88][89] The European Union fears this will lead to further Balkanization in the region.[90]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).^ Suetonius, Tiberius 16,17 ^ Miller, Norma. Tacitus: Annals I, 2002, ISBN 1-85399-358-1. It had originally been joined to Illyricum, but after the great Illyrian/Pannonian revolt of AD 6 it was made a separate province with its own governor ^ Stipčević, Aleksandar, The Illyrians: History and Culture, 1974, Noyess Press ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Malcolm 2002. ^ Ardian, Adzanela (Axhanela) (2004). Illyrian Bosnia and Herzegovina-an overview of a cultural legacy. Centre for Balkan Studies, Online Balkan Centre. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017. ^ a b Robert J. Donia; John VA Fine (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. Columbia University Press. pp. 14–16. ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. The Balkans from Constantinople to Communism, pp. 28–30. Palgrave Macmillan (2004) ^ Fine 1991, p. 53, 56. ^ a b Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 404–408, 424–425, 444. ISBN 9780199752720. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. ^ Fine 1991, p. 53(I):The Croats settled in Croatia, Dalmatia, and western Bosnia. The rest of Bosnia seems to have been territory between Serb and Croatian rule. ^ Malcolm 2002, p. 8:The Serbs settled in an area corresponding to modern south-western Serbia (a territory which later in the middle ages became known as Raška or Rascia), and gradually extended their rule into the territories of Duklje or Dioclea (Montenegro) and Hum or Zachumlje (Hercegovina). The Croats settled in areas roughly corresponding to modern Croatia, and probably also including most of Bosnia proper, apart from the eastern strip of the Drina valley. ^ a b c Basic 2009, p. 123. ^ Basic 2009, p. 123–28. ^ Fine 1991, p. 53. ^ Fine 1991, p. 223. ^ Paul Mojzes. Religion and the war in Bosnia. Oxford University Press, 2000, p 22; "Medieval Bosnia was founded as an independent state (Banate) by Ban Kulin (1180–1204).". ^ Fine 1991, p. 288. ^ Robert J. Donia, John V.A Fine (2005). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 9781850652120. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015., p. 71; In the Middle Ages the Bosnians called themselves "Bosnians" or used even more local (county, regional) names. ^ Kolstø, Pål (2005). Myths and boundaries in south-eastern Europe. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781850657675. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2015., p. 120; ..medieval Bosnia was a country of one people, of the single Bosnian people called the Bošnjani, who belonged to three confessions. ^ John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. (28 April 1994). "What is a Bosnian?". London Review of Books. London Review of Books; Vol.16 No.8. 28 April 1994. 16 (8): 9–10. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2016. ^ "Declared as national monument". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. ^ Anđelić Pavao, Krunidbena i grobna crkva bosanskih vladara u Milima (Arnautovićima) kod Visokog. Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja XXXIV/1979., Zemaljski muzej Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, 1980,183–247 ^ Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 496. ISBN 0-521-27485-0. ^ "Bosnia and Herzegovina - Ottoman Bosnia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2020. ^ Isailovović, Neven (2018). "Pomeni srpskog imena u srednjovjekovnim bosanskim ispravama". Srpsko pisano nasljeđe i istorija srednjovjekovne Bosne i Huma: 276. ^ Buzov, Snježana (2004). "Ottoman Perceptions of Bosnia as Reflected in the Works of Ottoman Authors who Visited or Lived in Bosnia". In Koller, Markus; Karpat, Kemal H. (eds.). Ottoman Bosnia: A History in Peril. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 83–92. ISBN 978-0-2992-0714-4. ^ Velikonja 2003, pp. 29–30. ^ Syed, M.H.; Akhtar, S.S.; Usmani, B.D. (2011). Concise History of Islam. Na. Vij Books India Private Limited. p. 473. ISBN 978-93-82573-47-0. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2021. ^ a b c Riedlmayer, Andras (1993). A Brief History of Bosnia–Herzegovina Archived 18 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The Bosnian Manuscript Ingathering Project. ^ a b c Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod; ISBN 9958-815-00-1 ^ Koller, Markus (2004). Bosnien an der Schwelle zur Neuzeit : eine Kulturgeschichte der Gewalt. Munich: Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-486-57639-9. ^ Hajdarpasic, Edin (2015). Whose Bosnia? Nationalism and Political Imagination in the Balkans, 1840-1914. Cornell University Press. pp. 6–13. ISBN 9780801453717. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2020. ^ Hajdarpasic 2015, p. 161–165. ^ Sugar, Peter (1963). Industrialization of Bosnia-Hercegovina : 1878-1918. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295738146. ^ Albertini 2005, p. 94. ^ Albertini 2005, p. 140. ^ Albertini 2005, p. 227. ^ Keil, Soeren (2013). Multinational Federalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. London: Routledge. pp. 61–62. ^ Schachinger, Werner (1989). Die Bosniaken kommen: Elitetruppe in der k.u.k. Armee, 1879–1918. Leopold Stocker. ^ Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2013. The role of the Schutzkorps, auxiliary militia raised by the Austro-Hungarians, in the policy of anti-Serb repression is moot ^ a b c Velikonja 2003, p. 141. ^ Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2013. ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485The Bosnian wartime militia (Schutzkorps), which became known for its persecution of Serbs, was overwhelmingly Muslim.

^ Danijela Nadj. "An International Symposium "Southeastern Europe 1918–1995"". Hic.hr. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2006. ^ "Balkan 'Auschwitz' haunts Croatia". BBC News. 25 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012. ^ Yeomans, Rory (2012). Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941-1945. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0822977933. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2020. ^ Pavković, Aleksandar (1996). The Fragmentation of Yugoslavia: Nationalism in a Multinational State. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-23037-567-3. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020. ^ Rogel, Carole (1998). The Breakup of Yugoslavia and the War in Bosnia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-3132-9918-6. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2020. ^ Ramet (2006), pgg. 118. ^ Velikonja 2003, p. 179. ^ Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015. ^ Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 256–261. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015. ^ Hoare, Marko Attila (2006). Genocide and Resistance in Hitler's Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks 1941–1943. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-726380-8. ^ a b Philip J. Cohen (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 109–10. ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7. ^ a b Geiger, Vladimir (2012). "Human Losses of the Croats in World War II and the Immediate Post-War Period Caused by the Chetniks (Yugoslav Army in the Fatherand) and the Partisans (People's Liberation Army and the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia/Yugoslav Army) and the Communist Authorities: Numerical Indicators". Review of Croatian History. Croatian Institute of History. VIII (1): 85–87. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015. ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 259. ^ Lepre, George (1997). Himmler's Bosnian Division: The Waffen-SS Handschar Division 1943–1945. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-7643-0134-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2015. ^ Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul (1999). The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. M.E. Sharpe. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-5632-4308-0. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2020. ^ Hadžijahić, Muhamed (1973), "Muslimanske rezolucije iz 1941 godine [Muslim resolutions of 1941]", Istorija Naroda Bosne i Hercegovine (in Serbo-Croatian), Sarajevo: Institut za istoriju radničkog pokreta, p. 277, archived from the original on 2 January 2022, retrieved 2 January 2022 ^ Redžić, Enver (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. London: Frank Cass. pp. 225–227. ^ Marko Attila Hoare. "The Great Serbian threat, ZAVNOBiH and Muslim Bosniak entry into the People's Liberation Movement" (PDF). anubih.ba. Posebna izdanja ANUBiH. p. 123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2020. ^ Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia manipulations with the number Second World War victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0-919817-32-7. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016. ^ Stojic, Mile (2005). Branko Mikulic – socialist emperor manqué Archived 9 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. BH Dani ^ Popovski, I. (2017). A Short History of South East Europe. Lulu.com. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-365-95394-1. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2021. ^ "The Balkans: A post-Communist History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2006. ^ "Bosnia - Herzegovina". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Self-Determination. 21 November 1995. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021. ^ "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)". Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. ^ "Prlic et al. Initial Indictment". United Nations. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2010. ^ "The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, Case NO: IT-01-47-PT (Amended Indictment)" (PDF). 11 January 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2009. ^ "The Referendum on Independence in Bosnia–Herzegovina: February 29 – March 1, 1992". Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 1992. p. 19. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2009. ^ Bose, Sumantra (2009). Contested lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus, and Sri Lanka. Harvard University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780674028562. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ D. Grant, Thomas (2009). Admission to the United Nations: Charter Article 4 and the Rise of Universal Organization. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 226. ISBN 978-9004173637. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2004. Indiana University Press. p. 379. ISBN 0-271-01629-9. ^ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict – A. Historical background". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. ^ "ICTY: The attack against the civilian population and related requirements". Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. ^ The Geography of Genocide, Allan D. Cooper, p. 178, University Press of America, 2008, ISBN 0-7618-4097-4 ^ "Judgement". UN. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2013. ^ "Press Release". UN. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2013. ^ "Crimes in Stolac Municipality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2009. ^ "Indictment". UN. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 12 February 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2013. ^ "The Yugoslav War - Boundless World History". Lumen Learning – Simple Book Production. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021. ^ "Bosnian protests: A Balkan Spring?". bbc.co.uk. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ "Građanski bunt u BiH". klix.ba. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ Bilefsky, Dan (8 February 2014). "Protests Over Government and Economy Roil Bosnia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ "Bosnian Protesters Torch Government Buildings in Sarajevo, Tuzla". rferl.org. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ "Bosnia–Hercegovina protests break out in violence". bbc.co.uk. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ "Bosnian protesters storm government buildings". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014. ^ "Bosnian Serb police drill seen as separatist 'provocation'". AP NEWS. 22 October 2021. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021. ^ "Bosnia is in danger of breaking up, warns top international official". the Guardian. 2 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021. ^ "Bosnian leader stokes fears of Balkan breakup". BBC News. 3 November 2021. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Stay safe

WARNING: Due to the constant landmine threat it is better not to leave paved roads, even for a pee-break in areas you are not familiar with.

WARNING: Due to the constant landmine threat it is better not to leave paved roads, even for a pee-break in areas you are not familiar with.

Land mine warning sign

Land mine warning signBe very careful when travelling off the beaten path in Bosnia and Herzegovina: it is still clearing many of the estimated 5 million land mines left around the countryside during the Bosnian War of 1992–1995. Whenever you're in rural areas, try to stay on paved areas if possible. Never touch any unknown item. Some of the houses and private properties that were abandoned by their owners were often rigged with mines during the war, and so they still pose a threat to anyone who trespasses. If an area or property looks abandoned, stay away from it. If you suddenly find a suspicious or unknown object, you must report it to the police, as this will help to keep locals and future visitors safe.

Bosnia experiences very little violent crime. However, in the old centre of Sarajevo and in other cities such as Mostar and Banja Luka, beware of pickpockets.