Buddhas of Bamiyan

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were two 6th-century monumental Buddhist statues in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan. Located 130 kilometres (81 mi) to the northwest of Kabul, at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 ft), carbon dating of the structural components of the Buddhas has determined that the smaller 38 m (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" was built around 570 CE, and the larger 55 m (180 ft) "Western Buddha" was built around 618 CE, which would date both to the time when the Hephthalites ruled the region. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site of historical Afghan Buddhism, it was a holy site for Buddhists on the Silk Road. However, in March 2001, both statues were destroyed by the Taliban following an order from their leader Mullah Muhammad Omar; the Taliban government of the Islamic Emirate had condemned the Bamiyan Buddhas as idols, invoking the Muslim concept of shirk. International and local opinion strongly condemned the destruction of the Buddhas....Read more

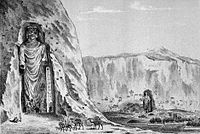

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were two 6th-century monumental Buddhist statues in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan. Located 130 kilometres (81 mi) to the northwest of Kabul, at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 ft), carbon dating of the structural components of the Buddhas has determined that the smaller 38 m (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" was built around 570 CE, and the larger 55 m (180 ft) "Western Buddha" was built around 618 CE, which would date both to the time when the Hephthalites ruled the region. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site of historical Afghan Buddhism, it was a holy site for Buddhists on the Silk Road. However, in March 2001, both statues were destroyed by the Taliban following an order from their leader Mullah Muhammad Omar; the Taliban government of the Islamic Emirate had condemned the Bamiyan Buddhas as idols, invoking the Muslim concept of shirk. International and local opinion strongly condemned the destruction of the Buddhas.

The statues represented a later evolution of the classic blended style of Greco-Buddhist art at Gandhara. The larger statue was named "Salsal" ("the light shines through the universe") and was referred as a male. The smaller statue is called "Shah Mama" ("Queen Mother") and is identified as a female figure.

Technically, both were reliefs: at the rear, they each merged into the cliff wall. The main bodies were hewn directly from the sandstone cliffs, but details were modeled in mud mixed with straw, coated with stucco. This coating, the majority of which wore away long ago, was painted to enhance the expressions of the faces, hands, and folds of the robes; the larger one was painted carmine red, and the smaller one was painted multiple colours. The lower parts of the statues' arms were constructed from the same mud-straw mix, supported on wooden armatures. It is believed that the upper parts of their faces consisted of huge wooden masks. Rows of holes held wooden pegs that stabilized the outer stucco.

The Buddhas were surrounded by numerous caves and surfaces decorated with paintings. It is thought that these mostly dated from the 6th to 8th centuries CE and had come to an end with the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan. The smaller works of art are considered as an artistic synthesis of Buddhist art and Gupta art from ancient India, with influences from the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, as well as the Tokhara Yabghus.

Panorama of the northern cliff of the Valley of Bamyan, with the Western and Eastern Buddhas at each end (before destruction), surrounded by a multitude of Buddhist caves.[1]Commissioning

Panorama of the northern cliff of the Valley of Bamyan, with the Western and Eastern Buddhas at each end (before destruction), surrounded by a multitude of Buddhist caves.[1]Commissioning

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were commissioned under the rule of the Hephthalite Principalities of Tokharistan and northern Afghanistan (c. 557-625 CE).[2][3][4]

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were commissioned under the rule of the Hephthalite Principalities of Tokharistan and northern Afghanistan (c. 557-625 CE).[2][3][4]Bamyan lies on the Silk Road, which runs through the Hindu Kush mountain region in the Bamyan Valley. The Silk Road has been historically a caravan route linking the markets of China with those of the Western world. It was the site of several Buddhist monasteries, and a thriving center for religion, philosophy, and art. Monks at the monasteries lived as hermits in small caves carved into the side of the Bamyan cliffs. Most of these monks embellished their caves with religious statuary and elaborate, brightly colored frescoes, sharing the culture of Gandhara.

The Great Buddhas of Bamiyan were built circa 600 CE under the Hephthalites, who at the time ruled as principalities in the areas of Tokharistan and northern Afghanistan.[2][4] Bamyan had been a Buddhist religious site from the 2nd century CE under the Kushans, and remained so up to the time of the Muslim conquest of the Abbasid Caliphate under Al-Mahdi in 770 CE. It became again Buddhist from 870 CE until the final Islamic conquest of 977 CE under the Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty.[5] Murals in the adjoining caves have been carbon dated from 438 to 980 CE, suggesting that Buddhist artistic activity continued down to the final occupation by the Muslims.[5]

The two most prominent statues were the giant standing sculptures of the Buddhas Vairocana and Sakyamuni (Gautama Buddha), identified by the different mudras performed. The Buddha popularly called "Solsol" measured 55 meters tall, and "Shahmama" 38 meters. The niches in which the figures stood are 58 and 38 meters respectively from bottom to top.[6][7] Before being blown up in 2001, they were the largest examples of standing Buddha carvings in the world (the 8th century Leshan Giant Buddha is taller,[8] but is sitting).

Mapping of the 38 meter smaller Eastern Buddha, dated to 591–644 CE, and its surrounding caves and chapels.[5]

Mapping of the 38 meter smaller Eastern Buddha, dated to 591–644 CE, and its surrounding caves and chapels.[5]Following the destruction of the statues in 2001, carbon dating of organic internal structural components found in the rubble has determined that the two Buddhas were built c. 600 CE, with narrow dates of between 544 and 595 CE for the 38-meter Eastern Buddha, and between 591 and 644 CE for the larger Western Buddha.[5] Recent scholarship has also been giving broadly similar dates based on stylistic and historical analysis, although the similarities with the Art of Gandhara had generally encouraged an earlier dating in older literature.[5]

Historic documentation refers to celebrations held every year attracting numerous pilgrims, with offers being made to the monumental statues.[9] They were perhaps the most famous cultural landmarks of the region, and the site was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site along with the surrounding cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamyan Valley. Their colour faded through time.[10]

Pre-modern eraChinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang visited the site on 30 April 630,[11][12][13] and described Bamyan in the Da Tang Xiyu Ji as a flourishing Buddhist center "with more than ten monasteries and more than a thousand monks". He also noted that both Buddha figures were "decorated with gold and fine jewels" (Wriggins, 1995). Intriguingly, Xuanzang mentions a third, even larger, reclining statue of the Buddha.[14][13] A monumental seated Buddha, similar in style to those at Bamyan, still exists in the Bingling Temple caves in China's Gansu province.

Add new comment