Banff National Park is Canada's oldest national park, established in 1885 as Rocky Mountains Park. Located in Alberta's Rocky Mountains, 110–180 kilometres (68–112 mi) west of Calgary, Banff encompasses 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 sq mi) of mountainous terrain, with many glaciers and ice fields, dense coniferous forest, and alpine landscapes. Provincial forests and Yoho National Park are neighbours to the west, while Kootenay National Park is located to the south and Kananaskis Country to the southeast. The main commercial centre of the park is the town of Banff, in the Bow River valley.

The Canadian Pacific Railway was instrumental in Banff's early years, building the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, and attracting tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees from World War I, and through Great Depression-era public works projects. The Icefie...Read more

Banff National Park is Canada's oldest national park, established in 1885 as Rocky Mountains Park. Located in Alberta's Rocky Mountains, 110–180 kilometres (68–112 mi) west of Calgary, Banff encompasses 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 sq mi) of mountainous terrain, with many glaciers and ice fields, dense coniferous forest, and alpine landscapes. Provincial forests and Yoho National Park are neighbours to the west, while Kootenay National Park is located to the south and Kananaskis Country to the southeast. The main commercial centre of the park is the town of Banff, in the Bow River valley.

The Canadian Pacific Railway was instrumental in Banff's early years, building the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, and attracting tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees from World War I, and through Great Depression-era public works projects. The Icefields Parkway extends from Lake Louise, connecting to Jasper National Park in the north.

Since the 1960s, park accommodations have been open all year, with annual tourism visits to Banff increasing to over 5 million in the 1990s. Millions more pass through the park on the Trans-Canada Highway. As Banff has over three million visitors annually, the health of its ecosystem has been threatened. In the mid-1990s, Parks Canada responded by initiating a two-year study which resulted in management recommendations and new policies that aim to preserve ecological integrity.

Banff National Park has a subarctic climate with three ecoregions, including montane, subalpine, and alpine. The forests are dominated by Lodgepole pine at lower elevations and Engelmann spruce in higher ones below the treeline, above which is primarily rocks and ice. Mammal species such as the grizzly bear, cougar, wolverine, elk, bighorn sheep and moose are found, along with hundreds of bird species. Reptiles and amphibians are also found but only a limited number of species have been recorded.

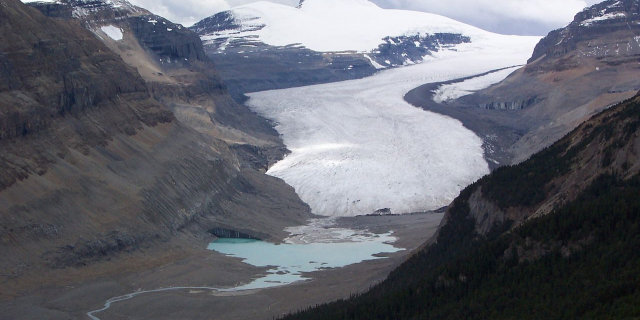

The mountains are formed from sedimentary rocks which were pushed east over newer rock strata, between 80 and 55 million years ago. Over the past few million years, glaciers have at times covered most of the park, but today are found only on the mountain slopes though they include the Columbia Icefield, the largest uninterrupted glacial mass in the Rockies. Erosion from water and ice have carved the mountains into their current shapes.

View from the summit of Sulphur Mountain, showing Banff and the surrounding areas

View from the summit of Sulphur Mountain, showing Banff and the surrounding areasThroughout its history, Banff National Park has been shaped by tension between conservationist and land exploitation interests. The park was established on November 25, 1885, as Banff Hot Springs Reserve,[1] in response to conflicting claims over who discovered hot springs there and who had the right to develop the hot springs for commercial interests. The conservationists prevailed when Prime Minister John A. Macdonald set aside the hot springs as a small protected reserve, which was later expanded to include Lake Louise and other areas extending north to the Columbia Icefield.[2]

Indigenous peoplesArchaeological evidence found at Vermilion Lakes indicates the first human activity in Banff to 10,300 B.P.[3] Prior to European contact, the area that is now Banff National Park was home to many Indigenous Peoples, including the Stoney Nakoda, Ktunaxa, Tsuut'ina, Kainaiwa, Piikani, Siksika, and Plains Cree .[4][5] Indigenous Peoples utilized the area to hunt, fish, trade, travel, survey and practice culture.[4][5] Many areas within Banff National Park are still known by their Stoney Nakoda names such as Lake Minnewanka and the Waputik Range. Cave and Basin served as an important cultural and spiritual site for the Stoney Nakoda.[5]

With the admission of British Columbia to Canada on July 20, 1871, Canada agreed to build a transcontinental railroad. Construction of the railroad began in 1875, with Kicking Horse Pass chosen, over the more northerly Yellowhead Pass, as the route through the Canadian Rockies.[2] Ten years later, on November 7, 1885, the last spike was driven in Craigellachie, British Columbia.[2]

Rocky Mountains Park establishedWith conflicting claims over the discovery of hot springs in Banff, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald decided to set aside a small reserve of 26 square kilometres (10 sq mi) around the hot springs at Cave and Basin as a public park known as the Banff Hot Springs Reserve in 1885. Under the Rocky Mountains Park Act, enacted on June 23, 1887, the park was expanded to 674 km2 (260 sq mi)[6] and named Rocky Mountains Park. This was Canada's first national park, and the third established in North America, after Yellowstone and Mackinac National Parks. The Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Springs Hotel and Lake Louise Chalet to attract tourists and increase the number of rail passengers.[2]

Banff Springs Hotel, 1902

Banff Springs Hotel, 1902The Stoney Nakoda First Nation were removed from Banff National Park between the years 1890 and 1920. The park was designed to appeal to sportsmen, and tourists. The exclusionary policy met the goals of sports hunting, tourism, and game conservation, as well as of those attempting to "civilize" the First Nations of the area.[7]

Early on, Banff was popular with wealthy European and American tourists, the former of which arrived in Canada via trans-Atlantic luxury liner and continued westward on the railroad.[6] Some visitors participated in mountaineering activities, often hiring local guides. Guides Jim and Bill Brewster founded one of the first outfitters in Banff.[8] From 1906, the Alpine Club of Canada organized climbs, hikes and camps in the park.[9]

By 1911, Banff was accessible by automobile from Calgary.[9] Beginning in 1916, the Brewsters offered motorcoach tours of Banff.[8] In 1920, access to Lake Louise by road was available, and the Banff-Windermere Road opened in 1923 to connect Banff with British Columbia.[9]

Canadian Pacific Railway advertising brochure, highlighting Mount Assiniboine and Banff scenery, c. 1917

Canadian Pacific Railway advertising brochure, highlighting Mount Assiniboine and Banff scenery, c. 1917In 1902, the park was expanded to cover 11,400 km2 (4,400 sq mi), encompassing areas around Lake Louise, and the Bow, Red Deer, Kananaskis, and Spray rivers. Bowing to pressure from grazing and logging interests, the size of the park was reduced in 1911 to 4,663 km2 (1,800 sq mi), eliminating many eastern foothills areas from the park. Park boundaries changed several more times up until 1930, when the area of Banff was fixed at 6,697 km2 (2,586 sq mi), with the passage of the National Parks Act.[6] The Act, which took effect May 30, 1930, also renamed the park Banff National Park, named for the Canadian Pacific Railway station, which in turn was named after the Banffshire region in Scotland.[10] With the construction of a new east gate in 1933, Alberta transferred 0.84 km2 (0.32 sq mi) to the park. This, along with other minor changes in the park boundaries in 1949, set the area of the park at 6,641 km2 (2,564 sq mi).[9]

Coal miningIn 1877, the First Nations of the area signed Treaty 7, which gave Canada rights to explore the land for resources. At the beginning of the 20th century, coal was mined near Lake Minnewanka in Banff. For a brief period, a mine operated at Anthracite but was shut down in 1904. The Bankhead mine, at Cascade Mountain, was operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway from 1903 to 1922. In 1926, the town was dismantled, with many buildings moved to the town of Banff and elsewhere.[11]

Internment and work campsDuring World War I, immigrants from Austria-Hungary and Germany were sent to Banff to work in internment camps.[12] The main camp was located at Castle Mountain, and was moved to Cave and Basin during winter.[12] Much early infrastructure and road construction was done by men of various Slavic origins although Ukrainians constituted a majority of those held in Banff.[13] Historical plaques and a statue erected by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association commemorate those interned at Castle Mountain, and at Cave and Basin National Historic Site where an interpretive pavilion dealing with Canada's first national internment operations opened in September 2013.[14]

Castle Mountain internment camp, 1915

Castle Mountain internment camp, 1915In 1931, the Government of Canada enacted the Unemployment and Farm Relief Act which provided public works projects in the national parks during the Great Depression.[15] In Banff, workers constructed a new bathhouse and pool at Upper Hot Springs, to supplement Cave and Basin.[13] Other projects involved road building in the park, tasks around the Banff townsite and construction of a highway connecting Banff and Jasper.[13] In 1934, the Public Works Construction Act was passed, providing continued funding for the public works projects. New projects included construction of a new registration facility at Banff's east gate and construction of an administrative building in Banff. By 1940, the Icefields Parkway reached the Columbia Icefield area of Banff and connected Banff and Jasper.[16] Most of the infrastructure present in the national park dates from public work projects enacted during the Great Depression.[15]

Alternative service camps for conscientious objectors were set up in Banff during World War II, with camps located at Lake Louise, Stoney Creek, and Healy Creek. These camps were largely populated by Mennonites from Saskatchewan.[17]

Winter tourismWinter tourism in Banff began in February 1917, with the first Banff Winter Carnival. It was marketed to a regional middle class audience, and became the centerpiece of local boosters aiming to attract visitors, which were a low priority for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).[18] The carnival featured a large ice palace, which in 1917 was built by World War I internees. Carnival events included cross-country skiing, ski jumping, curling, snowshoe, and skijoring.[19] In the 1930s, the first downhill ski resort, Sunshine Village, was developed by the Brewsters. Mount Norquay ski area was also developed during the 1930s, with the first chair lift installed there in 1948.[6]

Since 1968, when the Banff Springs Hotel was winterized, Banff has been a year-round destination.[20] In the 1950s, the Trans-Canada Highway was constructed, providing another transportation corridor through the Bow Valley, making the park more accessible.[9]

Canada launched several bids to host the Winter Olympics in Banff, with the first bid for the 1964 Winter Olympics, which were eventually awarded to Innsbruck, Austria. Canada narrowly lost a second bid, for the 1968 Winter Olympics, which were awarded to Grenoble, France. Once again, Banff launched a bid to host the 1972 Winter Olympics, with plans to hold the Olympics at Lake Louise. The 1972 bid was controversial, as environmental lobby groups strongly opposed the bid, which had sponsorship from Imperial Oil.[6] Bowing to pressure, Jean Chrétien, then the Minister of Environment, the government department responsible for Parks Canada, withdrew support for the bid, which was eventually lost to Sapporo, Japan.[6] When nearby Calgary hosted the 1988 Winter Olympics, the cross-country ski events were held at the Canmore Nordic Centre Provincial Park at Canmore, Alberta, located just outside the eastern gates of Banff National Park on the Trans-Canada Highway.

ConservationSince the original Rocky Mountains Park Act, subsequent acts and policies placed greater emphasis on conservation. With public sentiment tending towards environmentalism, Parks Canada issued major new policy in 1979, which emphasized conservation. The National Parks Act was amended in 1988, which made preserving ecological integrity the first priority in all park management decisions. The Act also required each park to produce a management plan, with greater public participation.[6]

In 1984, Banff was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site, together with the other national and provincial parks that form the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks, for the mountain landscapes containing mountain peaks, glaciers, lakes, waterfalls, canyons and limestone caves as well as fossil beds. With this designation came added obligations for conservation.[21]

During the 1980s, Parks Canada moved to privatize many park services such as golf courses, and added user fees for use of other facilities and services to help deal with budget cuts. In 1990, the town of Banff was incorporated, giving local residents more say regarding any proposed developments.[22]

In the 1990s, development plans for the park, including expansion at Sunshine Village, were under fire with lawsuits filed by Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS).[6] In the mid-1990s, the Banff-Bow Valley Study was initiated to find ways to better address environmental concerns, and issues relating to development in the park.[23]

Add new comment