Yosemite National Park ( yoh-SEM-ih-tee) is a national park in California. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service and covers 759,620 acres (1,187 sq mi; 3,074 km2) in four counties – centered in Tuolumne and Mariposa, extending north and east to Mono and south to Madera. Designated a World Heritage Site in 1984, Yosemite is internationally recognized for its granite cliffs, waterfalls, clear streams, giant sequoia groves, lakes, mountains, meadows, glaciers, and biological diversity. Almost 95 percent of the park is designated wilderness. Yosemite is one of the largest and least fragmented habitat blocks in the Sierra Nevada.

Its geology is characterized by granite and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada...Read more

Yosemite National Park ( yoh-SEM-ih-tee) is a national park in California. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service and covers 759,620 acres (1,187 sq mi; 3,074 km2) in four counties – centered in Tuolumne and Mariposa, extending north and east to Mono and south to Madera. Designated a World Heritage Site in 1984, Yosemite is internationally recognized for its granite cliffs, waterfalls, clear streams, giant sequoia groves, lakes, mountains, meadows, glaciers, and biological diversity. Almost 95 percent of the park is designated wilderness. Yosemite is one of the largest and least fragmented habitat blocks in the Sierra Nevada.

Its geology is characterized by granite and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and tilted to form its unique slopes, which increased the steepness of stream and river beds, forming deep, narrow canyons. About one million years ago glaciers formed at higher elevations. They moved downslope, cutting and sculpting the U-shaped Yosemite Valley.

European American settlers first entered the valley in 1851. Other travelers entered earlier, but James D. Savage is credited with discovering the area that became Yosemite National Park. Native Americans had inhabited the region for nearly 4,000 years, although humans may have first visited as long as 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Yosemite was critical to the development of the concept of national parks. Galen Clark and others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Yosemite Grant of 1864 that declared Yosemite as federally preserved land. In 1890, John Muir led a successful movement to motivate Congress to establish Yosemite Valley and its surrounding areas as a National Park. This helped pave the way for the National Park System. Yosemite draws about four million visitors annually. Most visitors spend the majority of their time in the valley's seven square miles (18 km2). The park set a visitation record in 2016, surpassing five million visitors for the first time.

The indigenous natives of Yosemite called themselves the Ahwahneechee, meaning "dwellers" in Ahwahnee.[1] The Ahwahneechee People were the only tribe that lived within the park boundaries, but other tribes lived in surrounding areas. Together they formed a larger Indigenous population in California, called the Southern Sierra Miwok.[2] They are related to the Northern Paiute and Mono tribes. Other tribes like the Central Sierra Miwoks and the Yokuts, who both lived in the San Joaquin Valley and central California, visited Yosemite to trade and intermarry.[3][page needed] This resulted in a blending of culture that helped preserve their presence in Yosemite after early American settlements and urban development threatened their survival.[2] Vegetation and game in the region were similar to modern times; acorns were a dietary staple, as well as other seeds and plants, salmon and deer.[2]

The 1848-1855 California Gold Rush was a major event impacting the native population. It drew more than 90,000 European Americans to the area in less than two years, causing competition for resources between gold miners and residents.[4] About 70 years before the Gold Rush, the indigenous population was estimated to be 300,000, quickly dropping to 150,000, and just ten years later, only about 50,000 remained.[5] The reasons for such a decline included disease, birth rate decreases, starvation, and conflicts from the American Indian Wars. The conflict in Yosemite is known as the Mariposa War. It started in December 1850 when California funded a state militia to drive Native people from contested territory to suppress Native American resistance to the European American influx.[6]

Yosemite tribes often stole from settlers and miners, sometimes killing them, in retribution for the extermination/domestication of their people, and loss of their lands and resources.[5] The War and formation of the Mariposa Battalion was partially the result of a single incident involving James Savage, a Fresno trader whose trading post was attacked in December, 1850. After the incident, Savage rallied other miners and gained the support of local officials to pursue a war against the Natives. He was appointed United States Army Major and leader of the Mariposa Battalion in the beginning of 1851.[5] He and Captain John Boling were responsible for pursuing the Ahwahneechee people, led by Chief Tenaya and driving them west, and out of Yosemite.[7][5] In March 1851 under Savage's command, the Mariposa Battalion captured about 70 Ahwahneechee and planned to take them to a reservation in Fresno, but they escaped. Later in May, under the command of Boling, the battalion captured 35 Ahwahneechee, including Chief Tenaya, and marched them to the reservation. Most were allowed to eventually leave and the rest escaped.[5] Tenaya and others fled across the Sierra Nevada and settled with the Mono Lake Paiutes. Tenaya and some of his companions were ultimately killed in 1853 either over stealing horses or a gambling conflict. The survivors of Tenaya's group and other Ahwahneechee were absorbed into the Mono Lake Paiute tribe.[5][8][9]

Sculpture of Chief Tenaya made by Sal Maccarone for the Tenaya Lodge in Yosemite National Park

Sculpture of Chief Tenaya made by Sal Maccarone for the Tenaya Lodge in Yosemite National ParkAccounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor Lafayette Bunnell, who later wrote about his awestruck impressions of the valley in The Discovery of the Yosemite. Bunnell is credited with naming Yosemite Valley, based on his interviews with Chief Tenaya. Bunnell wrote that Chief Tenaya was the founder of the Ahwahnee colony.[10] Bunnell falsely believed that the word "Yosemite" meant "full-grown grizzly bear."[11]

Indigenous peoples' continuing presence Basket woven by Lucy Telles (1885-1955), a Mono Lake Paiute and Southern Sierra Miwok Native American artist from the Yosemite region

Basket woven by Lucy Telles (1885-1955), a Mono Lake Paiute and Southern Sierra Miwok Native American artist from the Yosemite regionAfter the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite Ahwahneechee tribe members there were forced to relocate to a village constructed in 1851 by the state government.[5] They learned to live within this camp and their limited rights, adapting to the changed environment by entering the tourism industry through employment and small businesses, manufacturing and selling goods and providing services.[2] Their villages were destroyed and their people forced to relocate four different times. The U.S. Army was responsible for the village's destruction in 1851 and 1906, and the National Park Service was responsible for it in 1929 and 1969.[5] In 1969, the National Park Service evicted the remaining Native people from their residences and destroyed their village as part of a fire-fighting exercise.[6] A reconstructed "Indian Village of Ahwahnee" sits behind the Yosemite Museum, located next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center.[12][13][14]

By the late 19th century, the population of all native inhabitants in Yosemite was difficult to determine, estimates ranged from thirty to several hundred. The Ahwahneechee people and their descendants were hard to identify.[5] The last full-blooded Ahwahneechee died in 1931. Her name was Totuya, or Maria Lebrado. She was the granddaughter of Chief Tenaya and one of many forced out of her ancestral homelands.[5][6] The Ahwahneechee live through the memory of their descendants, their fellow Yosemite Natives, and through the Yosemite exhibit in the Smithsonian and the Yosemite Museum.[5] As a method of self-preservation and resilience, the Indigenous people of California proposed treaties in 1851 and 1852 that would have established land reservations for them, but Congress refused to ratify them.[5] The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation is seeking tribal sovereignty and federal recognition.[6][15] The National Park Service created policies to protect sacred sites and allow Native People to return to their homelands and use National Park resources.[15][16]

Early tourists

In 1855, entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings, artist Thomas Ayres and two others were the first tourists to visit.[17] Hutchings and Ayres were responsible for much of Yosemite's earliest publicity, writing articles and special issues about the valley.[18] Ayres' style was detailed with exaggerated angularity. His works and written accounts were distributed nationally, and an exhibition of his drawings was held in New York City. Hutchings' publicity efforts between 1855 and 1860 increased tourism to Yosemite.[19] Natives supported the growing tourism industry by working as laborers or maids. Later, they performed dances for tourists, acted as guides, and sold handcrafted goods, notably woven baskets.[2] The Indian village and its peoples fascinated visitors, especially James Hutchings who advocated for Yosemite tourism. He and others considered the indigenous presence to be one of Yosemite's greatest attractions.[2]

Wawona was an early Indian encampment for Nuchu and Ahwahneechee people who were captured and relocated to a reservation on the Fresno River by Savage and the Mariposa Battalion in March 1851.[20] Galen Clark discovered the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoia in Wawona in 1857. He had simple lodgings and roads built. In 1879, the Wawona Hotel was built to serve tourists visiting Mariposa Grove.[21] As tourism increased, so did the number of trails and hotels to build on it.[22]

The Wawona Tree, also known as the Tunnel Tree, was a giant sequoia that grew in the Mariposa Grove. It was 234 feet (71 m) tall, and was 90 ft (27 m) in circumference. When a carriage-wide tunnel was cut through the tree in 1881, it became even more popular as a tourist photo attraction. Carriages and automobiles, traversed the road that passed through the tree. The tree was permanently weakened by the tunnel, and it fell in 1969 under a heavy load of snow. It was estimated to have been 2,100 years old.[23]

Yosemite's first concession was established in 1884 when John Degnan and his wife established a bakery and store.[24] In 1916, the National Park Service granted a 20-year concession to the Desmond Park Service Company. It bought out or built hotels, stores, camps, a dairy, a garage, and other park facilities.[25] The Hotel Del Portal was completed in 1908 by a subsidiary of the Yosemite Valley Railroad. It was located at El Portal, California just outside of Yosemite.[26][27]

The Curry Company started in 1899, led by David and Jennie Curry to provide concessions. They founded Camp Curry, now Curry Village.[28]

Park service administrators felt that limiting the number of concessionaires in the park would be more financially sound. The Curry Company and its rival, the Yosemite National Park Company, were forced to merge in 1925 to form the Yosemite Park & Curry Company (YP&CC).[29] The company built the Ahwahnee Hotel in 1926–27.[30]

Yosemite Grant A view of the park and Vernal Fall, photographed by photographer Eadweard Muybridge in 1872.

A view of the park and Vernal Fall, photographed by photographer Eadweard Muybridge in 1872.Concerned by the impact of commercial interests, citizens including Galen Clark and Senator John Conness advocated protection for the area.[31] The 38th United States Congress passed legislation that was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864, creating the Yosemite Grant.[32][33] This is the first time land was set aside specifically for preservation and public use by the U.S. government, and set a precedent for the 1872 creation of Yellowstone national park, the nation's first.[34] Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove were ceded to California as a state park, and a board of commissioners was established two years later.[35]

Galen Clark was appointed by the commission as the Grant's first guardian, but neither Clark nor the commissioners had the authority to evict homesteaders (which included Hutchings).[32] The issue was not settled until 1872 when the homesteader land holdings were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court.[36] Clark and the commissioners were ousted in a dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1880.[37] The two Supreme Court decisions affecting management of the Yosemite Grant are considered precedents in land management law.[38] Hutchings became the new park guardian.[39]

Tourist access to the park improved, and conditions in the Valley became more hospitable. Tourism significantly increased after the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, while the long horseback ride to reach the area was a deterrent.[32] Three stagecoach roads were built in the mid-1870s to provide better access for the growing number of visitors.[40]

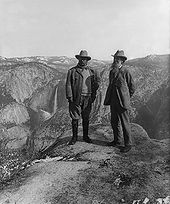

John Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist and explorer. Muir's leadership ensured that many National Parks were left untouched, including Yosemite.[41]

Muir wrote articles popularizing the area and increasing scientific interest in it. Muir was one of the first to theorize that the major landforms in Yosemite Valley were created by alpine glaciers, bucking established scientists such as Josiah Whitney.[39] Muir wrote scientific papers on the area's biology. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted emphasized the importance of conservation of Yosemite Valley.[42]

Increased protection efforts

Overgrazing of meadows (especially by sheep), logging of giant sequoia, and other damage led Muir to become an advocate for further protection. Muir convinced prominent guests of the importance of putting the area under federal protection. One such guest was Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine. Muir and Johnson lobbied Congress for the Act that created Yosemite National Park on October 1, 1890.[43] The State of California, however, retained control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove. Muir's writings raised awareness about the damage caused by sheep grazing, and he actively campaigned to virtually eliminate grazing from the Yosemite's high-country.[44]

The newly created national park came under the jurisdiction of the United States Army's Troop I of the 4th Cavalry on May 19, 1891, which set up camp in Wawona with Captain Abram Epperson Wood as acting superintendent.[43] By the late 1890s, sheep grazing was no longer a problem, and the Army made other improvements. However, the cavalry could not intervene to ease the worsening conditions. From 1899 to 1913, cavalry regiments of the Western Department, including the all Black 9th Cavalry (known as the "Buffalo Soldiers") and the 1st Cavalry, stationed two troops at Yosemite.

Bridalveil Fall and El Capitan, by Carleton Watkins (c. 1880)

Bridalveil Fall and El Capitan, by Carleton Watkins (c. 1880)Muir and his Sierra Club continued to lobby the government and influential people for the creation of a unified Yosemite National Park. In May 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt camped with Muir near Glacier Point for three days. On that trip, Muir convinced Roosevelt to take control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove away from California and return it to the federal government. In 1906, Roosevelt signed a bill that shifted control.[45]

National Park ServiceThe National Park Service (NPS) was formed in 1916, and Yosemite was transferred to that agency's jurisdiction. Tuolumne Meadows Lodge, Tioga Pass Road, and campgrounds at Tenaya and Merced lakes were also completed in 1916.[46] Automobiles started to enter the park in ever-increasing numbers following the opening of all-weather highways to the park. The Yosemite Museum was founded in 1926 through the efforts of Ansel Franklin Hall.[47] In the 1920s, the museum featured Native Americans practicing traditional crafts, and many Southern Sierra Miwok continued to live in Yosemite Valley until they were evicted from the park in the 1960s.[48] Although the NPS helped create a museum that included Native American culture, its early actions and organizational values were dismissive of Yosemite Natives and the Ahwahneechee.[5] NPS in the early 20th century criticized and restricted the expression of indigenous culture and behavior. For example, park officials penalized Natives for playing games and drinking during the Indian Field Days of 1924.[2] In 1929, Park Superintendent Charles G. Thomson concluded that the Indian village was aesthetically unpleasant and was limiting white settler development and ordered the camp to be burned down.[5] In 1969, many Native residents left in search of work as a result of the decline in tourism. NPS demolished their empty houses, evicted the remaining residents, and destroyed the entire village.[5] This was the last Indigenous settlement within the park.[5][6]

In 1903, a dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley in the northwestern region of the park was proposed. Its purpose was to provide water and hydroelectric power to San Francisco. Muir and the Sierra Club opposed the project, while others, including Gifford Pinchot, supported it.[49] In 1913, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was approved via passage of the Raker Act.[50]

In 1918, Clare Marie Hodges was hired as the first female Park Ranger in Yosemite.[51] Following Hodges in 1921, Enid Michael was hired as a seasonal Park Ranger[51] and continued to serve in that position for 20 years.[51]

O'Shaughnessy Dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley

O'Shaughnessy Dam in Hetch Hetchy ValleyIn 1937, conservationist Rosalie Edge, head of the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), successfully lobbied Congress to purchase about 8,000 acres (3,200 ha) of old-growth sugar pines on the perimeter of Yosemite National Park that were to be logged.[52]

By 1968, traffic congestion and parking in Yosemite Valley during the summer months has become a concern. NPS reduced artificial inducements to visit the park, such as the Firefall, in which red-hot embers were pushed off a cliff near Glacier Point at night.[53]

In 1984, preservationists persuaded Congress to designate 677,600 acres (274,200 ha), or about 89 percent of the park, as the Yosemite Wilderness. As a wilderness area, it would be preserved in its natural state with humans being only temporary visitors.[54]

In 2016, The Trust for Public Land (TPL) purchased Ackerson Meadow, a 400-acre tract (160 ha) on the western edge of the park for $2.3 million. Ackerson Meadow was originally included in the proposed 1890 park boundary, but never acquired by the federal government. The purchase and donation of the meadow was made possible through a cooperative effort by TPL, NPS, and Yosemite Conservancy. On September 7, 2016, NPS accepted the donation of the land, making the meadow the largest addition to Yosemite since 1949.[55]

Add new comment