Valletta

Valletta (, Maltese: il-Belt Valletta, Maltese pronunciation: [vɐlˈlɛt.tɐ]) is an administrative unit and the capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 was 6,444. According to the data from 2020 by Eurostat, the Functional Urban Area and metropolitan region covered the whole island and has a population of 480,134. Valletta is the southernmost capital of Europe, and at just 0.61 square kilometres (0.24 sq mi), it is the European Union's smallest capital city.

Valletta's 16th-century buildings were constructed by the Knights Hospitaller. The city was named after Jean Parisot de Valette, who succeeded in defending the island from an Ottoman invasion during the Great Siege of Malta. The city is Baroque in character, with elements of Manner...Read more

Valletta (, Maltese: il-Belt Valletta, Maltese pronunciation: [vɐlˈlɛt.tɐ]) is an administrative unit and the capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 was 6,444. According to the data from 2020 by Eurostat, the Functional Urban Area and metropolitan region covered the whole island and has a population of 480,134. Valletta is the southernmost capital of Europe, and at just 0.61 square kilometres (0.24 sq mi), it is the European Union's smallest capital city.

Valletta's 16th-century buildings were constructed by the Knights Hospitaller. The city was named after Jean Parisot de Valette, who succeeded in defending the island from an Ottoman invasion during the Great Siege of Malta. The city is Baroque in character, with elements of Mannerist, Neo-Classical and Modern architecture, though the Second World War left major scars on the city, particularly the destruction of the Royal Opera House. The city was officially recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1980. The city has 320 monuments, all within an area of 0.55 square kilometres (0.21 sq mi), making it one of the most concentrated historic areas in the world. Sometimes called an "open-air museum", Valletta was chosen as the European Capital of Culture in 2018. Valletta was also listed as the sunniest city in Europe in 2016.

The city is noted for its fortifications, consisting of bastions, curtains and cavaliers, along with the beauty of its Baroque palaces, gardens and churches.

Former mural at Is-Suq tal-Belt illustrating the city's construction

Former mural at Is-Suq tal-Belt illustrating the city's constructionThe peninsula was previously called Xagħret Mewwija (Mu' awiya – Meuia; named during the Arab period[1])[2][3] or Ħal Newwija.[4] Mewwija refers to a sheltered place.[5] Some authors state that the extreme end of the peninsula was known as Xebb ir-Ras (Sheb point), of which name origins from the lighthouse on site.[6][7] A family which surely owned land became known as Sceberras, now a Maltese surname as Sciberras.[8] At one point the entire peninsula became known as Sceberras.

![]() Hospitaller Malta 1566–1798

Hospitaller Malta 1566–1798![]() French Republic 1798–1800

French Republic 1798–1800![]() Protectorate of Malta 1800–1813

Protectorate of Malta 1800–1813![]() Crown Colony of Malta 1813–1964

Crown Colony of Malta 1813–1964![]() State of Malta 1964–1974

State of Malta 1964–1974![]() Republic of Malta 1974–present

Republic of Malta 1974–present

Recent scholarly studies have however shown that the Xeberras phrase is of Punic origin and means 'the headland' and 'the middle peninsula' as it actually is.[9]

Order of Saint John The Ottoman army bombs the Knights' Three Cities from the peninsula of Sciberras during the 1565 Great Siege.

The Ottoman army bombs the Knights' Three Cities from the peninsula of Sciberras during the 1565 Great Siege. The nave of Saint John's Co-Cathedral

The nave of Saint John's Co-Cathedral Grandmaster's Palace

Grandmaster's Palace Valletta and the Grand Harbour c. 1801

Valletta and the Grand Harbour c. 1801The building of a city on the Sciberras Peninsula had been proposed by the Order of Saint John as early as 1524.[10] Back then, the only building on the peninsula was a small watchtower[11] dedicated to Erasmus of Formia (Saint Elmo), which had been built in 1488.[12]

In 1552, the Aragonite watchtower was demolished and the larger Fort Saint Elmo was built in its place.[13]

In the Great Siege of 1565, Fort Saint Elmo fell to the Ottomans, but the Order eventually won the siege with the help of Sicilian reinforcements. The victorious Grand Master, Jean de Valette, immediately set out to build a new fortified city on the Sciberras Peninsula to fortify the Order's position in Malta and bind the Knights to the island. The city took his name and was called La Valletta.[14]

The Grand Master asked the European kings and princes for help, receiving a lot of assistance due to the increased fame of the Order after their victory in the Great Siege. Pope Pius V sent his military architect, Francesco Laparelli, to design the new city, while Philip II of Spain sent substantial monetary aid. The foundation stone of the city was laid by Grand Master de Valette on 28 March 1566. He placed the first stone in what later became Our Lady of Victories Church.[15]

In his book Dell'Istoria della Sacra Religione et Illustrissima Militia di San Giovanni Gierosolimitano (English: The History of the Sacred Religion and Illustrious Militia of St John of Jerusalem), written between 1594 and 1602, Giacomo Bosio writes that when the cornerstone of Valletta was placed, a group of Maltese elders said: "Iegi zimen en fel wardia col sceber raba iesue uquie" (Which in modern Maltese reads, "Jiġi żmien li fil-Wardija [l-Għolja Sciberras] kull xiber raba' jiswa uqija", and in English, "There will come a time when every piece of land on Sciberras Hill will be worth its weight in gold").[16]

De Valette died from a stroke on 21 August 1568 at age 74 and never saw the completion of his city. Originally interred in the church of Our Lady of the Victories, his remains now rest in St. John's Co-Cathedral among the tombs of other Grand Masters of the Knights of Malta.[15]

Francesco Laparelli was the city's principal designer and his plan departed from medieval Maltese architecture, which exhibited irregular winding streets and alleys. He designed the new city on a rectangular grid plan, and without any collacchio (an area restricted for important buildings). The streets were designed to be wide and straight, beginning centrally from the City Gate and ending at Fort Saint Elmo (which was rebuilt) overlooking the Mediterranean; certain bastions were built 47 metres (154 ft) high. His assistant was the Maltese architect Girolamo Cassar, who later oversaw the construction of the city himself after Laparelli's death in 1570.[15]

The Ufficio delle Case regulated the building of the city as a planning authority.[17]

The city of Valletta was mostly completed by the early 1570s, and it became the capital on 18 March 1571 when Grand Master Pierre de Monte moved from his seat at Fort St Angelo in Birgu to the Grandmaster's Palace in Valletta.

Turner's depiction of the Grand Harbour, National Museum of Fine Arts

Turner's depiction of the Grand Harbour, National Museum of Fine ArtsSeven Auberges were built for the Order's Langues, and these were complete by the 1580s.[18][19] An eighth Auberge, Auberge de Bavière, was later added in the 18th century.[20]

In Antoine de Paule's reign, it was decided to build more fortifications to protect Valletta, and these were named the Floriana Lines after the architect who designed them, Pietro Paolo Floriani of Macerata.[21] During António Manoel de Vilhena's reign, a town began to form between the walls of Valletta and the Floriana Lines, and this evolved from a suburb of Valletta to Floriana, a town in its own right.[22]

In 1634, a gunpowder factory explosion killed 22 people in Valletta.[23] In 1749, Muslim slaves plotted to kill Grandmaster Pinto and take over Valletta, but the revolt was suppressed before it even started due to their plans leaking out to the Order.[24] Later on in his reign, Pinto embellished the city with Baroque architecture, and many important buildings such as Auberge de Castille were remodeled or completely rebuilt in the new architectural style.[25]

In 1775, during the reign of Ximenes, an unsuccessful revolt known as the Rising of the Priests occurred in which Fort Saint Elmo and Saint James Cavalier were captured by rebels, but the revolt was eventually suppressed.[26]

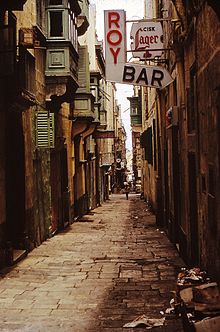

French occupation and British rule Early morning in 1967 on the notorious Strait Street known to generations of British Servicemen (especially to sailors on shore leave) as "The Gut". Bars and bordellos abounded, and brawls were common, but its popularity never waned.

Early morning in 1967 on the notorious Strait Street known to generations of British Servicemen (especially to sailors on shore leave) as "The Gut". Bars and bordellos abounded, and brawls were common, but its popularity never waned.In 1798, the French invaded the island and expelled the Order.[27] After the Maltese rebelled, French troops continued to occupy Valletta and the surrounding harbour area, until they capitulated to the British in September 1800. In the early 19th century, the British Civil Commissioner, Henry Pigot, agreed to demolish the majority of the city's fortifications.[28] The demolition was again proposed in the 1870s and 1880s, but it was never carried out and the fortifications have survived largely intact.[10]

Eventually building projects in Valletta resumed under British rule. These projects included widening gates, demolishing and rebuilding structures, widening newer houses over the years, and installing civic projects. The Malta Railway, which linked Valletta to Mdina, was officially opened in 1883.[29] It was closed down in 1931 after buses became a popular means of transport.

In 1939, Valletta was abandoned as the headquarters of the Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet due to its proximity to Italy and the city became a flash point during the subsequent two-year long Siege of Malta.[30] German and Italian air raids throughout the Second World War caused much destruction in Valletta and the rest of the harbor area. The Royal Opera House, constructed at the city entrance in the 19th century, was one of the buildings lost to the raids.[13]

In 1980, the 24th Chess Olympiad took place in Valletta.[31]

The entire city of Valletta has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1980, along with Megalithic Temples of Malta and the Hypogeum of Ħal-Saflieni.[32][33] On 11 November 2015, Valletta hosted the Valletta Summit on Migration in which European and African leaders discussed the European migrant crisis.[34] After that, on 27 November 2015, the city also hosted part of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 2015.[35]

Valletta was the European Capital of Culture in 2018.[36]

Add new comment