St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London. Its dedication in honour of Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. The present structure, which was completed in 1710, is a Grade I listed building that was designed in the English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. The cathedral's reconstruction was part of a major rebuilding programme initiated in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London. The earlier Gothic cathedral (Old St Paul's Cathedral), largely destroyed in the Great Fire, was a central focus for medieval and early modern London, including Paul's walk and St Paul's Churchyard, being the site of St Paul's Cross.

Th...Read more

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London. Its dedication in honour of Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604. The present structure, which was completed in 1710, is a Grade I listed building that was designed in the English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. The cathedral's reconstruction was part of a major rebuilding programme initiated in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London. The earlier Gothic cathedral (Old St Paul's Cathedral), largely destroyed in the Great Fire, was a central focus for medieval and early modern London, including Paul's walk and St Paul's Churchyard, being the site of St Paul's Cross.

The cathedral is one of the most famous and recognisable sights of London. Its dome, surrounded by the spires of Wren's City churches, has dominated the skyline for over 300 years. At 365 ft (111 m) high, it was the tallest building in London from 1710 to 1963. The dome is still one of the highest in the world. St Paul's is the second-largest church building in area in the United Kingdom, after Liverpool Cathedral.

Services held at St Paul's have included the funerals of Admiral Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher; jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria; an inauguration service for the Metropolitan Hospital Sunday Fund; peace services marking the end of the First and Second World Wars; the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer; the launch of the Festival of Britain; and the thanksgiving services for the Silver, Golden, Diamond, and Platinum Jubilees and the 80th and 90th birthdays of Queen Elizabeth II. St Paul's Cathedral is the central subject of much promotional material, as well as of images of the dome surrounded by the smoke and fire of the Blitz. The cathedral is a working church with hourly prayer and daily services. The tourist entry fee at the door is £23 for adults (January 2023, cheaper if booked online), but no charges are made to worshippers attending advertised services.

The nearest London Underground station is St Paul's, which is 130 yards (120 m) away from St Paul's Cathedral.

The location of Londinium's original cathedral is unknown, but legend and medieval tradition claims it was St Peter upon Cornhill. St Paul is an unusual attribution for a cathedral, and suggests there was another one in the Roman period. Legends of St Lucius link St Peter upon Cornhill as the centre of the Roman Londinium Christian community. It stands upon the highest point in the area of old Londinium, and it was given pre-eminence in medieval procession on account of the legends. There is, however, no other reliable evidence and the location of the site on the Forum makes it difficult for it to fit the legendary stories. In 1995, a large fifth-century building on Tower Hill was excavated, and has been claimed as a Roman basilica, possibly a cathedral, although this is speculative. [1][2]

The Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden argued that a temple to the goddess Diana had stood during Roman times on the site occupied by the medieval St Paul's Cathedral.[3] Wren reported that he had found no trace of any such temple during the works to build the new cathedral after the Great Fire, and Camden's hypothesis is no longer accepted by modern archaeologists.[4]

Pre-Norman cathedralThere is evidence for Christianity in London during the Roman period, but no firm evidence for the location of churches or a cathedral. Bishop Restitutus is said to have represented London at the Council of Arles in 314 AD.[5] A list of the 16 "archbishops" of London was recorded by Jocelyn of Furness in the 12th century, claiming London's Christian community was founded in the second century under the legendary King Lucius and his missionary saints Fagan, Deruvian, Elvanus and Medwin. None of that is considered credible by modern historians but, although the surviving text is problematic, either Bishop Restitutus or Adelphius at the 314 Council of Arles seems to have come from Londinium.[a]

Bede records that in AD 604 Augustine of Canterbury consecrated Mellitus as the first bishop to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Saxons and their king, Sæberht. Sæberht's uncle and overlord, Æthelberht, king of Kent, built a church dedicated to St Paul in London, as the seat of the new bishop.[6] It is assumed, although not proved, that this first Anglo-Saxon cathedral stood on the same site as the later medieval and the present cathedrals.

On the death of Sæberht in about 616, his pagan sons expelled Mellitus from London, and the East Saxons reverted to paganism. The fate of the first cathedral building is unknown. Christianity was restored among the East Saxons in the late seventh century and it is presumed that either the Anglo-Saxon cathedral was restored or a new building erected as the seat of bishops such as Cedd, Wine and Erkenwald, the last of whom was buried in the cathedral in 693.

Earconwald was consecrated bishop of London in 675, and is said to have bestowed great cost on the fabric, and in later times he almost occupied the place of traditionary, founder: the veneration paid to him is second only to that which was rendered to St. Paul.[7] Erkenwald would become a subject of the important High Medieval poem St Erkenwald.

King Æthelred the Unready was buried in the cathedral on his death in 1016; the tomb is now lost. The cathedral was burnt, with much of the city, in a fire in 1087, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[8]

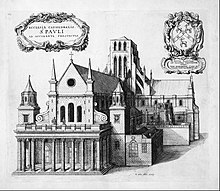

Old St Paul's Reconstructed image of Old St Paul's before 1561, with intact spire

Reconstructed image of Old St Paul's before 1561, with intact spire Shrine of St Erkenwald, relics removed 1550, lost as a monument in the Great Fire of London

Shrine of St Erkenwald, relics removed 1550, lost as a monument in the Great Fire of LondonThe fourth St Paul's, generally referred to as Old St Paul's, was begun by the Normans after the 1087 fire. A further fire in 1135 disrupted the work, and the new cathedral was not consecrated until 1240. During the period of construction, the style of architecture had changed from Romanesque to Gothic and this was reflected in the pointed arches and larger windows of the upper parts and East End of the building. The Gothic ribbed vault was constructed, like that of York Minster, of wood rather than stone, which affected the ultimate fate of the building.[citation needed]

An enlargement programme commenced in 1256. This "New Work" was consecrated in 1300 but not complete until 1314. During the later Medieval period St Paul's was exceeded in length only by the Abbey Church of Cluny and in the height of its spire only by Lincoln Cathedral and St. Mary's Church, Stralsund. Excavations by Francis Penrose in 1878 showed that it was 585 feet (178 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide (290 feet (88 m) across the transepts and crossing). The spire was about 489 feet (149 m) in height.[citation needed] By the 16th century the building was deteriorating.

The English Reformation under Henry VIII and Edward VI (accelerated by the Chantries Acts) led to the destruction of elements of the interior ornamentation and the chapels, shrines, and chantries.

The shrine of Erkenwald (d. 693) rivaled that of St Edward in Westminster Abbey, and his relics were removed during the mayoralty of Sir Rowland Hill

The shrine of Erkenwald (d. 693) rivaled that of St Edward in Westminster Abbey, and his relics were removed during the mayoralty of Sir Rowland HillThe would come to include the removal of the cathedral's collection of relics, which by the sixteenth century was understood to include:[9][10]

the body of St Erkenwald both arms of St Mellitus a knife thought to belong to Jesus hair of Mary Magdalen blood of St Paul milk of the Virgin Mary the head of St John the skull of Thomas Becket the head and jaw of King Ethelbert part of the wood of the cross, a stone of the Holy Sepulchre, a stone from the spot of the Ascension, and some bones of the eleven thousand virgins of Cologne. Old St Paul's in 1656 by Wenceslaus Hollar, showing the rebuilt west facade

Old St Paul's in 1656 by Wenceslaus Hollar, showing the rebuilt west facadeIn October 1538, an image of St Erkenwald, probably from the shrine, was delivered to the master of the king's jewels. Other images may have survived, at least for a time. More systematic iconoclasm happened in the reign of Edward VI: the Grey Friar's Chronicle reports that the rood and other images were destroyed in November 1547.

In late 1549, at the height of the iconoclasm of the reformation, Sir Rowland Hill altered the route of his Lord Mayor's day procession and said a de profundis at the tomb of Erkenwald.[11] Later in Hill's mayoralty of (1550)[12] the high altar of St Paul's was removed[13] overnight[14] to be destroyed,[15] an occurrence that provoked a fight in which a man was killed.[16] Hill had ordered, unusually for the time, that St Barnabus's Day would not be kept as a public holiday ahead of these events.

Three years later, by October 1553, "Alle the alteres and chappelles in alle Powlles churche" were taken down.[12] In August, 1553, the dean and chapter were cited to appear before Queen Mary's commissioners.[7]

Some of the buildings in the St Paul's churchyard were sold as shops and rental properties, especially to printers and booksellers. In 1561 the spire was destroyed by a lightning strike, an event that Roman Catholic writers claimed was a sign of God's judgment on England's Protestant rulers. Bishop James Pilkington preached a sermon in response, claiming that the lightning strike was a judgement for the irreverent use of the cathedral building.[17] Immediate steps were taken to repair the damage, with the citizens of London and the clergy offering money to support the rebuilding.[18] However, the cost of repairing the building properly was too great for a country and city recovering from a trade depression. Instead, the roof was repaired and a timber "roo"’[clarification needed] put on the steeple.

In the 1630s a west front was added to the building by England's first classical architect, Inigo Jones. There was much defacing and mistreatment of the building by Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War, and the old documents and charters were dispersed and destroyed.[19][page needed] During the Commonwealth, those churchyard buildings that were razed supplied ready-dressed building material for construction projects, such as the Lord Protector's city palace, Somerset House. Crowds were drawn to the north-east corner of the churchyard, St Paul's Cross, where open-air preaching took place.[citation needed]

In the Great Fire of London of 1666, Old St Paul's was gutted.[20] While it might have been possible to reconstruct it, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style. This course of action had been proposed even before the fire.

Present St Paul's St Paul's Cathedral in 1896

St Paul's Cathedral in 1896The task of designing a replacement structure was officially assigned to Sir Christopher Wren on 30 July 1669.[21] He had previously been put in charge of the rebuilding of churches to replace those lost in the Great Fire. More than 50 city churches are attributable to Wren. Concurrent with designing St Paul's, Wren was engaged in the production of his five Tracts on Architecture.[22]

Wren had begun advising on the repair of the Old St Paul's in 1661, five years before the fire in 1666.[23] The proposed work included renovations to interior and exterior to complement the classical facade designed by Inigo Jones in 1630.[24] Wren planned to replace the dilapidated tower with a dome, using the existing structure as a scaffold. He produced a drawing of the proposed dome which shows his idea that it should span nave and aisles at the crossing.[25] After the Fire, it was at first thought possible to retain a substantial part of the old cathedral, but ultimately the entire structure was demolished in the early 1670s.

In July 1668 Dean William Sancroft wrote to Wren that he was charged by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in agreement with the Bishops of London and Oxford, to design a new cathedral that was "Handsome and noble to all the ends of it and to the reputation of the City and the nation".[26] The design process took several years, but a design was finally settled and attached to a royal warrant, with the proviso that Wren was permitted to make any further changes that he deemed necessary. The result was the present St Paul's Cathedral, still the second largest church in Britain, with a dome proclaimed as the finest in the world.[27] The building was financed by a tax on coal, and was completed within its architect's lifetime with many of the major contractors engaged for the duration.

The "topping out" of the cathedral (when the final stone was placed on the lantern) took place on 26 October 1708, performed by Wren's son Christopher Jr and the son of one of the masons.[28] The cathedral was declared officially complete by Parliament on 25 December 1711 (Christmas Day).[29] In fact, construction continued for several years after that, with the statues on the roof added in the 1720s. In 1716 the total costs amounted to £1,095,556[30] (£174 million in 2021).[31]

ConsecrationOn 2 December 1697, 31 years and 3 months after the Great Fire destroyed Old St Paul's, the new cathedral was consecrated for use. The Right Reverend Henry Compton, Bishop of London, preached the sermon. It was based on the text of Psalm 122, "I was glad when they said unto me: Let us go into the house of the Lord." The first regular service was held on the following Sunday.

Opinions of Wren's cathedral differed, with some loving it: "Without, within, below, above, the eye / Is filled with unrestrained delight",[32][page needed] while others hated it: "There was an air of Popery about the gilded capitals, the heavy arches ... They were unfamiliar, un-English ...".[33]

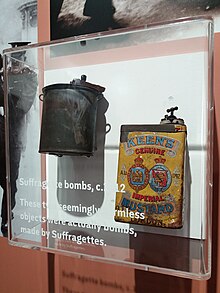

Since 1900 Suffragette terror attacks Two suffragette bombs on display at the City of London Police Museum in 2019. The bomb on the right was used in an attempted bombing of St. Paul's in 1913.

Two suffragette bombs on display at the City of London Police Museum in 2019. The bomb on the right was used in an attempted bombing of St. Paul's in 1913.St. Paul's was the target of two suffragette bombing attacks in 1913 and 1914 respectively, which nearly caused the destruction of the cathedral. This was as part of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign between 1912 and 1914, in which suffragettes from the Women's Social and Political Union, as part of their campaign for women's suffrage, carried out a series of politically motivated bombings and arson nationwide.[34] Churches were explicitly targeted by the suffragettes as they believed the Church of England was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage.[35] Between 1913 and 1914, 32 churches across Britain were attacked.[36]

The first attack on St. Paul's occurred on 8 May 1913, at the start of a sermon.[37] A bomb was heard ticking and discovered as people were entering the cathedral.[37] It was made out of potassium nitrate.[37] Had it exploded, the bomb likely would have destroyed the historic bishop's throne and other parts of the cathedral.[37] The remains of the device, which was made partly out of a mustard tin, are now on display at the City of London Police Museum.[37]

A second bombing of the cathedral by the suffragettes was attempted on 13 June 1914, however the bomb was again discovered before it could explode.[34] This attempted bombing occurred two days after a bomb had exploded at Westminster Abbey, which damaged the Coronation Chair and caused a mass panic for the exits.[37] Several other churches were bombed at this time, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square and the Metropolitan Tabernacle.[34]

War damage The iconic St Paul's Survives taken on 29 December 1940 of St Paul's during the Blitz

The iconic St Paul's Survives taken on 29 December 1940 of St Paul's during the BlitzThe cathedral survived the Blitz although struck by bombs on 10 October 1940 and 17 April 1941. The first strike destroyed the high altar, while the second strike on the north transept left a hole in the floor above the crypt.[38][39] The latter bomb is believed to have detonated in the upper interior above the north transept and the force was sufficient to shift the entire dome laterally by a small amount.[40][41]

On 12 September 1940 a time-delayed bomb that had struck the cathedral was successfully defused and removed by a bomb disposal detachment of Royal Engineers under the command of Temporary Lieutenant Robert Davies. Had this bomb detonated, it would have totally destroyed the cathedral; it left a 100-foot (30 m) crater when later remotely detonated in a secure location.[42] As a result of this action, Davies and Sapper George Cameron Wylie were each awarded the George Cross.[43] Davies' George Cross and other medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum, London.

One of the best known images of London during the war was a photograph of St Paul's taken on 29 December 1940 during the "Second Great Fire of London" by photographer Herbert Mason,[b] from the roof of a building in Tudor Street showing the cathedral shrouded in smoke. Lisa Jardine of Queen Mary, University of London, has written:[38]

Wreathed in billowing smoke, amidst the chaos and destruction of war, the pale dome stands proud and glorious—indomitable. At the height of that air-raid, Sir Winston Churchill telephoned the Guildhall to insist that all fire-fighting resources be directed at St Paul's. The cathedral must be saved, he said, damage to the fabric would sap the morale of the country.

Post-warOn 29 July 1981, the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer was held at the cathedral. The couple selected St Paul's over Westminster Abbey, the traditional site of royal weddings, because the cathedral offered more seating.[44]

Extensive copper, lead and slate renovation work was carried out on the Dome in 1996 by John B. Chambers. A 15-year restoration project—one of the largest ever undertaken in the UK—was completed on 15 June 2011.[45]

Occupy London Julian Assange speaks at the Occupy London outside the cathedral in the City of London on 15 October 2011.

Julian Assange speaks at the Occupy London outside the cathedral in the City of London on 15 October 2011.In October 2011 an anti-capitalism Occupy London encampment was established in front of the cathedral, after failing to gain access to the London Stock Exchange at Paternoster Square nearby. The cathedral's finances were affected by the ensuing closure. It was claimed that the cathedral was losing revenue of £20,000 per day.[46] Canon Chancellor Giles Fraser resigned, asserting his view that "evicting the anti-capitalist activists would constitute violence in the name of the Church".[47] The Dean of St Paul's, the Right Revd Graeme Knowles, then resigned too.[48] The encampment was evicted at the end of February 2012, by court order and without violence, as a result of legal action by the City of London Corporation.[49]

2019 terrorist plotOn 10 October 2019, Safiyya Amira Shaikh, a Muslim convert, was arrested following an MI5 and Metropolitan Police investigation. In September 2019, she had taken photos of the cathedral's interior. While trying to radicalise others using the Telegram messaging software, she planned to attack the cathedral and other targets such as a hotel and a train station using explosives. Shaikh pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[50]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Add new comment