Karlovy Vary

Karlovy Vary (Czech pronunciation: [ˈkarlovɪ ˈvarɪ] ; German: Karlsbad, formerly also spelled Carlsbad in English) is a spa city in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 49,000 inhabitants. It lies at the confluence of the rivers Ohře and Teplá. It is named after Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Bohemia, who founded the city.

Karlovy Vary is the site of numerous hot springs (13 main springs, about 300 smaller springs, and the warm-water Teplá River), and is the most visited spa town in the Czech Republic. The historic city centre with the spa cultural landscape is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation. It is the largest spa complex in Europe. In 2021, the city became part of the transnational UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name "Great Spa Towns of Europe" because of it...Read more

Karlovy Vary (Czech pronunciation: [ˈkarlovɪ ˈvarɪ] ; German: Karlsbad, formerly also spelled Carlsbad in English) is a spa city in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 49,000 inhabitants. It lies at the confluence of the rivers Ohře and Teplá. It is named after Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Bohemia, who founded the city.

Karlovy Vary is the site of numerous hot springs (13 main springs, about 300 smaller springs, and the warm-water Teplá River), and is the most visited spa town in the Czech Republic. The historic city centre with the spa cultural landscape is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation. It is the largest spa complex in Europe. In 2021, the city became part of the transnational UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name "Great Spa Towns of Europe" because of its spas and architecture from the 18th through 20th centuries.

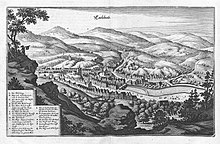

Karlovy Vary, 1650; engraving by Matthäus Merian

Karlovy Vary, 1650; engraving by Matthäus MerianAn ancient late Bronze Age fortified settlement was found in Drahovice. A Slavic settlement on the site of Karlovy Vary is documented by findings in Tašovice and Sedlec. People lived in close proximity to the site as far back as the 13th century and they must have been aware of the curative effects of thermal springs.[1]

From the end of the 12th century to the early 13th century, German settlers from nearby German-speaking regions came as settlers, craftsmen and miners to develop the region's economy. Eventually, Karlovy Vary/Karlsbad became a town with a German-speaking population.[2]

In 1325, Obora, a village in today's city area, was mentioned. Karlovy Vary as a small spa settlement was founded most likely around 1349.[1] According to legend, Charles IV organized an expedition into the forests surrounding modern-day Karlovy Vary during a stay in Loket. It is said that his party once discovered a hot spring by accident, and thanks to the water from the spring, Charles IV healed his injured leg.[3] On the site of a spring, he established a spa mentioned as in dem warmen Bade bey dem Elbogen in German, or Horké Lázně u Lokte (Hot Spas at the Loket).[4] The location was subsequently named "Karlovy Vary" after the emperor. Charles IV granted the town privileges on 14 August 1370. Earlier settlements can also be found on the outskirts of today's city.[1]

19th and 20th centuries Karlovy Vary in 1850

Karlovy Vary in 1850An important political event took place in the city in 1819, with the issuing of the Carlsbad Decrees following a conference there. Initiated by the Austrian Minister of State Klemens von Metternich, the decrees were intended to implement anti-liberal censorship within the German Confederation.

Due to publications produced by physicians such as David Becher and Josef von Löschner, the city developed into a spa resort in the 19th century and was visited by many members of European aristocracy as well as celebrities from many fields of endeavour. It became even more popular after railway lines were completed from Prague to Cheb in 1870.

The number of visitors rose from 134 families in the 1756 season to 26,000 guests annually at the end of the 19th century.[citation needed] The greatest year for tourism was 1911, when the number of visitors reached 70,956.[5] World War I ended the development of tourism. Other disasters for tourism were the world economic crisis and the beginning of World War II.[6]

At the end of World War I in 1918, the large German-speaking population of Bohemia was incorporated into the new state of Czechoslovakia in accordance with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919). As a result, the German-speaking majority of Karlovy Vary protested. A demonstration on 4 March 1919 passed peacefully, but later that month, six demonstrators were killed by Czech troops after a demonstration became unruly.[7]

According to the 1930 census, the city was home to 23,901 inhabitants – 20,856 were of German ethnicity, 1,446 of Czechoslovak ethnicity (Czech or Slovak), 243 of Jewish ethnicity, 19 of Hungarian ethnicity and 12 of Polish ethnicity.[8]

In 1938, the city was together with the rest of the Sudetenland annexed by Nazi Germany according to the terms of the Munich Agreement. During World War II, the Germans established a Gestapo prison here.[9] After the war, in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement and Beneš decrees, most German inhabitants were expelled.

After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, spas and tourism began to develop rapidly again. The spa buildings were reconstructed and the spa became competitive again within Europe.[6] The spa became popular with Russian clientele, and brought many Russian investors and developers to the city and its surroundings.[10]

Add new comment