The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: Islas Galápagos) are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the Equator 900 km (560 mi) west of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of slightly over 33,000 (2020). The province is divided into the cantons of San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz, and Isabela, the three most populated islands in the chain. The Galápagos are famous for their large number of endemic species, which were studied by Charles Darwin in the 1830s and inspired his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. All of these islands are protected as part of Ecuador's Galápagos National Park and Marine Reserve.

Thus far, there is no firm evidence that Polynesians or the indigenous peoples of South America reached the islands before their accidental discovery by Bishop Tomás de Berlanga in 1535. If some visitors did arrive...Read more

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: Islas Galápagos) are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the Equator 900 km (560 mi) west of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of slightly over 33,000 (2020). The province is divided into the cantons of San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz, and Isabela, the three most populated islands in the chain. The Galápagos are famous for their large number of endemic species, which were studied by Charles Darwin in the 1830s and inspired his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. All of these islands are protected as part of Ecuador's Galápagos National Park and Marine Reserve.

Thus far, there is no firm evidence that Polynesians or the indigenous peoples of South America reached the islands before their accidental discovery by Bishop Tomás de Berlanga in 1535. If some visitors did arrive, poor access to fresh water on the islands seems to have limited settlement. The Spanish Empire similarly ignored the islands, although during the Golden Age of Piracy various pirates used the Galápagos as a base for raiding Spanish shipping along the Peruvian coast. The goats and black and brown rats introduced during this period greatly damaged the existing ecosystems of several islands. English sailors were chiefly responsible for exploring and mapping the area. Darwin's voyage on HMS Beagle was part of an extensive British survey of the coasts of South America. Ecuador, which won its independence from Spain in 1822 and left Gran Colombia in 1830, formally occupied and claimed the islands on 12 February 1832 while the voyage was ongoing. José de Villamil, the founder of the Ecuadorian Navy, led the push to colonize and settle the islands, gradually supplanting the English names of the major islands with Spanish ones. The United States built the islands' first airport as a base to protect the western approaches of the Panama Canal in the 1930s. After World War II, its facilities were transferred to Ecuador. With the growing importance of ecotourism to the local economy, the airport modernized in the 2010s, using recycled materials for any expansion and shifting entirely to renewable energy sources to handle its roughly 300,000 visitors each year.

Whether Polynesians or the indigenous peoples of South America ever made it to the islands is disputed. Oceanic Pacific islands in the same general area as Galápagos—including Clipperton, Cocos, the Desventuradas, the Juan Fernández Islands, and the Revillagigedos—were all uninhabited when discovered by Europeans, with no evidence to indicate any prehistoric human activity.[1][2][3] The easternmost oceanic island in the South Pacific that was discovered with a human population was Easter Island,[2] whose Rapa Nui people are known to be Polynesian rather than South American.[4]

In 1572, the Spanish chronicler Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa claimed that Topa Inca Yupanqui, the second Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire, had visited the archipelago. There is, however, little evidence for this and many experts consider it a far-fetched legend, especially since the Incas were not typically a seafaring people.[5] A 1952 archaeological survey by Thor Heyerdahl and Arne Skjølsvold found potsherds and other artifacts from several sites on the islands that they claimed suggested visitation by South Americans during the pre-Columbian era.[6] The group located an Inca flute and shards from more than 130 pieces of ceramics, later identified as pre-Incan. However, no remains of graves, ceremonial vessels, or buildings have ever been found, suggesting no permanent settlement occurred before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century.[7] A 2016 reanalysis of Heyerdahl and Skjølsvold's archaeological sites rejected their conclusions. They found that—at all locations excavated by the 1952 survey—artifacts of Indian and European origin were interspersed without the distinct spatial or stratigraphic arrangement that would be expected from independent sequential deposition. (Heyerdahl and Skjølsvold had noted this in their original report while ignoring its implications.) Radiocarbon dates from the sites placed them in the post-Spanish era and preliminary paleoenvironmental analysis showed no disturbance older than 500 years before present, suggesting no evidence from the survey that the islands were visited prior to their Spanish discovery in 1535. The authors suggested that native artifacts found by Heyerdahl and Skjølsvold had probably been brought as mementos or souvenirs at the time of Spanish occupation.[8]

A 2008 report by archeologists from the Australian National University stated that certain Asia–Pacific taxa may have been growing in the Galápagos prior to 1535. This opens a direction for future research which might "constitute a strong line of evidence for accidental or deliberate landfall in the Galápagos by a Polynesian vessel",[2] although the report noted current scholarship finds no evidence that Pacific islands beyond Easter Island "play[ed] a 'stepping stone' role in the interaction between Amerindians or Polynesians in prehistory".[2] The lack of fresh water on the islands seems to have limited visits and settlement, if any ever occurred.

European discovery Detail of the Galápagos on Abraham Ortelius's 1570 map of the Americas

Detail of the Galápagos on Abraham Ortelius's 1570 map of the AmericasEuropean discovery of the Galápagos Islands is recorded occurring on 10 March 1535, when the Spanish bishop of Panama Tomás de Berlanga—sailing to Peru to adjudicate a dispute between Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro—drifted off course while his ship was becalmed in the Doldrums. They found the islands they visited uninhabited and so arid and barren that two men and ten horses died for lack of fresh water and the rest were forced to subsist on cactus pads.[9] The ship left them unclaimed and unsettled.[10] Berlanga, however, wrote a brief account of the islands, their condition, and their main wildlife for Charles V.

The Galápagos Islands first appeared on the maps of Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius around 1570.[11]

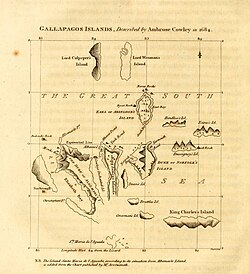

Pirate era The chart of the Galápagos published by the English pirate William Ambrosia Cowley in 1684, the source of many of the islands' English names

The chart of the Galápagos published by the English pirate William Ambrosia Cowley in 1684, the source of many of the islands' English names A manuscript map of the islands from the charts drafted by James Colnett of the British Royal Navy in 1793, adding additional names

A manuscript map of the islands from the charts drafted by James Colnett of the British Royal Navy in 1793, adding additional namesThe first English captain to visit the Galápagos Islands was Richard Hawkins in 1593.[citation needed] Until the early 19th century, the archipelago was often used as a hideout by (mostly English) pirates who attacked Spanish treasure fleets carrying gold, silver, and supplies from Peru to Panama and Spain.[12] The English pirate William Ambrosia Cowley thoroughly mapped the islands in 1684 while sailing on John Cook's Batchelor's or Bachelor's Delight and John Eaton's Nicholas as they raided Peruvian shipping. [13] One cargo captured that year was 7–8 tuns of quince marmalade, whose remains scattered pottery around the islands.[14][15][16] Publishing the first thorough chart of the islands, Cowley coined the English names for 16 of the islands, chiefly honoring English royalty, nobles, and Jamaican officials of the era who might provide future patronage.[13]

In 1793, during the early French Revolutionary Wars, the British captain James Colnett described the flora and fauna of Galápagos and suggested the islands could be used as a base for whalers operating in the Pacific. Colnett improved upon Cowley's chart, coining additional names[13] although accidentally transferring Cowley's Charles Island from Española to Floreana.[17] Whalers and maritime fur traders killed and captured thousands of the Galápagos tortoises to extract their fat. The tortoises could be kept on board ship as a means of providing of fresh protein, as these animals could survive for several months on board without any food or water. The hunting of the tortoises was responsible for greatly diminishing, and in some cases eliminating, certain species. Along with whalers came the fur-seal hunters, who brought the population of this animal close to extinction.

19th century A Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra) on Santa Cruz. C. nigra is the largest living species of tortoise, hunted to near extinction during the islands' whaling era.

A Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra) on Santa Cruz. C. nigra is the largest living species of tortoise, hunted to near extinction during the islands' whaling era. Gen. José de Villamil, founder of the Ecuadorian Navy and first governor of the islands

Gen. José de Villamil, founder of the Ecuadorian Navy and first governor of the islands The 1841 Admiralty chart drafted from FitzRoy's survey of the islands on HMS Beagle

The 1841 Admiralty chart drafted from FitzRoy's survey of the islands on HMS BeagleThe first known permanent human resident on Galápagos was Patrick Watkins, an Irish sailor who was marooned on the Floreana from 1807 to 1809. According to later accounts, Watkins managed to survive by hunting, growing vegetables and trading with visiting whalers[18][19] before stealing a longboat from a whaling ship, impressing five of its crew as his "slaves", and navigating to Guayaquil on the Ecuadorian mainland.[20] Watkins was the only one of the six to survive the journey.[20]

In 1818, the Nantucket whaleship Globe under Captain George Washington Gardner discovered a "mother lode" of sperm whales some thousand miles west of the South American coast approximately at the equator. He returned to Nantucket in 1820 with more than 2,000 barrels of sperm whale oil and the news of his discovery. This led to an influx of whaleships to exploit the new whaling ground and the Galápagos Islands became a frequent stop for the whalers both before and after visiting what came to be known as the Offshore Grounds. This led to the establishment in the Galápagos Islands of a kind of unofficial "post office" where whaleships stopped to pick up and drop off letters as well as for provisioning and repairing.[21]

In October 1820, the whaleship Essex out of Nantucket stopped at the Galápagos for these purposes on its way to the Offshore Grounds. On Colnett's Charles Island, while most of the crew were hunting tortoises one crewmember, English boatsteerer Thomas Chappel—for reasons still unclear—lit a fire which quickly burned out of control. Some of the tortoise hunters had a narrow escape and had to run a gauntlet of fire to get back to the ship. Soon almost the entire island was in flames. Crewmembers reported that after a day of sailing away they could still see the flames against the horizon. One crewmember who returned to the Galápagos several years afterward described the entire island as still a blackened wasteland.[22]

Ecuador won its independence from Spain in 1822 and left Gran Colombia in 1830. Gen. José de Villamil, the founder of the Ecuadorian Navy, led the push to colonize and settle the islands before Ecuador's neighbors or the European empires could occupy them.[23] He formed the Galapagos Settlement Company in mid-1831[24] and, with President Juan José Flores's support, sent Col. Ignacio Hernández with a dozen craftsmen to begin the settlement on Charles Island—renamed "Floriana" in the president's honour—early the next year.[25] Hernández conducted a formal ceremony of annexation on Floreana on 12 February 1832,[23] now celebrated locally as Galápagos Day or the Day of the Province. (Darwin's birthday was the same day,[26] as was Francisco de Orellana's arrival at the headwaters of the Amazon River in 1542, celebrated on the mainland as Amazon Day.) Villamil arrived in September and established Haven of Peace (Asilo de Paz or de la Paz) in the island's highlands.[25] The initial colonists who joined him were Ecuadorian soldiers—chiefly political prisoners[25]—whose death sentences were commuted in exchange for their agreement to permanently settle the islands with their families.[24] They were joined in October by additional artisans and farmers, bringing the population to about 120, at which point Villamil was formally made the area's first governor.[24] Villamil's lieutenant governor was the Norwegian-born[24] American and Chilean sailor and shipwright Nicholas Oliver Lawson.[25] Haven of Peace was originally successful and peaceful but, after being named a penal colony in March 1833, violence and costs began to rise.[27] Villamil was faced with bankruptcy by 1837 and resigned his post, founding a colony of 21 on Indefatigable Island—renamed Bolivia—and leaving Lawson as its mayor.[26] Gen. Villamil's successors—incompetent, strict, or both—prompted a bloody uprising in 1841 that caused most settlers to return to the mainland.[27] Villamil returned to try to rebuild afterwards but was unsuccessful and abandoned the attempt in 1848.[27]

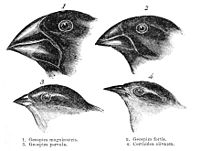

Gould's illustration of Darwin's finches

Gould's illustration of Darwin's finchesThe second voyage of HMS Beagle under captain Robert FitzRoy was undertaken to better survey the coasts and harbours of South America for the British Navy's Hydrographic Department. It reached the Galápagos on 15 September 1835 and—while surveying its islands, channels, and bays—the captain and others on the crew observed the geology, plants, and wildlife on Floreana, Isabela, and Santiago before continuing on their round-the-world expedition on October 20. The young naturalist Charles Darwin, primarily a geologist at the time, was struck by the many volcanic features they saw, later referring to the archipelago as "that land of craters". His study of several volcanic formations over the five weeks he stayed in the islands led to several important geological discoveries, including the first correct explanation for how volcanic tuff is formed.[28] Darwin noticed the mockingbirds differed between islands, though he thought the birds now known as Darwin's finches were unrelated to each other and did not bother labelling them by island.[29] Acting as governor of the islands while Villamil was on the mainland, Nicholas Lawson met Darwin and the British crew, mentioning in passing that the tortoises of the different islands could be easily identified by their different shells.[24][30] By the end of his voyage, Darwin was beginning to wonder if the distribution of the mockingbirds and the tortoises might "undermine the stability of Species".[31] Upon his return to England, analysis of the bird specimens he had collected showed that what had appeared to be many different species were actually finches displaying developments unique to the islands. The voyage became crucial in Darwin's development of his theory of evolution of species by natural selection, presented in the 1859 On the Origin of Species.[29]

The Englishman William Gurney became mayor of a new settlement on Chatham Island in 1844.[26]

In April 1888 USS Albatross, a Navy-crewed research vessel assigned to the United States Fish Commission, briefly touched eight islands in the Galapagos group for specimens;[32] this included Wreck Bay on Chatham Island (now San Cristóbal Island) on 4 April and Charles Island (now Floreana Island) on 8 April.

José Valdizán and Manuel Julián Cobos tried a new colonization, beginning the exploitation of a type of lichen found in the islands (Roccella portentosa) used as a coloring agent. After the assassination of Valdizán by some of his workers, Cobos brought from the continent to San Cristóbal Island a group of more than a hundred workers, and tried his luck at planting sugar cane. He ruled his plantation with an iron hand, which led to his assassination in 1904. In 1897, Antonio Gil began another plantation on Isabela Island.

Over the course of a whole year, from September 1904, an expedition of the Academy of Sciences of California, led by Rollo Beck, stayed in the Galápagos collecting scientific material on geology, entomology, ornithology, botany, zoology, and herpetology. Another expedition from that Academy was done in 1932 (Templeton Crocker Expedition) to collect insects, fish, shells, fossils, birds, and plants.

20th century Eleanor Roosevelt visiting U.S. servicemen at Beta Base (Seymour Airport) on Baltra during World War II[33]

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting U.S. servicemen at Beta Base (Seymour Airport) on Baltra during World War II[33] Admiralty chart of the Galápagos (1953)

Admiralty chart of the Galápagos (1953)For a long time during the early 1900s and at least through 1929, a cash-strapped Ecuador had reached out for potential buyers of the islands to alleviate financial troubles at home. The US had repeatedly expressed its interest in buying the islands for military use as they were positioned strategically guarding the Panama Canal.[34] Besides the United States, Japan, Germany and Chile also expressed interest in establishing bases in the islands at the turn of the century.[35][36] Chile had previously acquired the Straits of Magellan[37] and Easter Island for strategic reasons and lieutenant Gregorio Santa Cruz argued in 1903 that possessing an island in equatorial waters, like the Galápagos, would be of great benefit since the geopolitical situation of Chile was expected to drastically change when the Panama Canal opened. Another benefit would be to widen the security radius of Chile.[38] Chile was alarmed by the United States plans to establish a Guantanamo-like base in the Galápagos Islands since it would mean that Chile's nitrate-rich northern provinces would be within the range of United States Navy.[39] Ecuador's staunch resistance to a US purchase or bases in the islands can be credited to Chilean diplomacy, which in turn was informally backed on this issue by Great Britain and Germany.[39]

In the 1920s and 1930s, a small wave of European settlers arrived in the islands. There occurred a series of unsolved disappearances on the island of Floreana in the 1930s among the largely European expatriate residents at the time, which prompted the movies The Empress of Floreana and The Galápagos Affair: Satan Came to Eden. Ecuadorian laws provided all colonists with the possibility of receiving twenty hectares each of free land, the right to maintain their citizenship, freedom from taxation for the first ten years in Galápagos, and the right to hunt and fish freely on all uninhabited islands where they might settle.[40] The first European colonists to arrive were Norwegians who settled briefly on Floreana, before moving on to San Cristobal and Santa Cruz. A few years later, other colonists from Europe, America and Ecuador started arriving on the islands, seeking a simpler life.[41] Descendants of the Norwegian Kastdalen family and the German Angermeyer still live on the islands.

During World War II, Ecuador authorized the United States to establish a naval base in Baltra Island, and radar stations in other strategic locations. Baltra was established as a United States Army Air Force base. Baltra was given the name of "Beta Base" along with "Alpha Base" in Nicaragua and "Gamma Base" in Salinas (continental Ecuador). The Crews stationed at Baltra and the aforementioned locations established a geographic triangle of protection in charge of patrolling the Pacific for enemy submarines, and also provided protection for the Panama Canal. After the war, the facilities were given to the government of Ecuador. Today, the island continues as an official Ecuadorian military base. The foundations and other remains of the US base can still be seen as one crosses the island. In 1946, a penal colony was established on Isabela Island, but it was suspended in 1959.

Galápagos National Park was established in 1959,[42] with tourism starting to expand in the 1960s, imposing several restrictions upon the human population already living on the island. However, opportunities in the tourism, fishing, and farming industries attracted a mass of poor fishermen and farmers from mainland Ecuador. In the 1990s and 2000s, violent confrontations between parts of the local population and the Galápagos National Park Service occurred, including capturing and killing giant tortoises and holding staff of the Galápagos National Park Service hostage to obtain higher annual sea cucumber quotas.[43]

21st centuryIn May 2023, Credit Suisse said it would buy Ecuador's debt of $1.6 billion in a "Debt-for-nature swap". It will sell 2035 and 2040 bonds for Galapagos conservation at a reduced issue price. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation insures the deal, [44] which per Reuters was "in the works for more than a year", predating UBS takeover of Credit Suisse.[45]

Add new comment