Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( Scots: [ˈɛdɪnbʌrə]; Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Èideann [ˌt̪un ˈeːtʲən̪ˠ]) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. The city is located in south-east Scotland, and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth estuary and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh had a population of 506,520 in mid-2020, making it the second-most populous city in Scotland and the seventh-most populous in the United Kingdom.

Recognised as the capital of Scotland since at least the 15th century, Edinburgh is the seat of the Scottish Government, the Scottish Parliament, the highest courts in Scotland, and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. It is also the annual venue of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The city has long b...Read more

Edinburgh ( Scots: [ˈɛdɪnbʌrə]; Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Èideann [ˌt̪un ˈeːtʲən̪ˠ]) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. The city is located in south-east Scotland, and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth estuary and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh had a population of 506,520 in mid-2020, making it the second-most populous city in Scotland and the seventh-most populous in the United Kingdom.

Recognised as the capital of Scotland since at least the 15th century, Edinburgh is the seat of the Scottish Government, the Scottish Parliament, the highest courts in Scotland, and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. It is also the annual venue of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The city has long been a centre of education, particularly in the fields of medicine, Scottish law, literature, philosophy, the sciences and engineering. The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1582 and now one of three in the city, is considered one of the best research institutions in the world. It is the second-largest financial centre in the United Kingdom, the fourth largest in Europe, and the thirteenth largest internationally.

The city is a cultural centre, and is the home of institutions including the National Museum of Scotland, the National Library of Scotland and the Scottish National Gallery. The city is also known for the Edinburgh International Festival and the Fringe, the latter being the world's largest annual international arts festival. Historic sites in Edinburgh include Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the churches of St. Giles, Greyfriars and the Canongate, and the extensive Georgian New Town built in the 18th/19th centuries. Edinburgh's Old Town and New Town together are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which has been managed by Edinburgh World Heritage since 1999. The city's historical and cultural attractions have made it the UK's second-most visited tourist destination, attracting 4.9 million visits, including 2.4 million from overseas in 2018.

Edinburgh is governed by the City of Edinburgh Council, a unitary authority. The City of Edinburgh council area had an estimated population of 526,470 in mid-2021, and includes outlying towns and villages which are not part of Edinburgh proper. The city is in the Lothian region and was historically part of the shire of Midlothian (also called Edinburghshire).

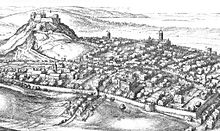

Edinburgh, showing Arthur's Seat, one of the earliest known sites of human habitation in the area

Edinburgh, showing Arthur's Seat, one of the earliest known sites of human habitation in the areaThe earliest known human habitation in the Edinburgh area was at Cramond, where evidence was found of a Mesolithic camp site dated to c. 8500 BC.[1] Traces of later Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements have been found on Castle Rock, Arthur's Seat, Craiglockhart Hill and the Pentland Hills.[2]

When the Romans arrived in Lothian at the end of the 1st century AD, they found a Brittonic Celtic tribe whose name they recorded as the Votadini.[3] The Votadini transitioned into the Gododdin kingdom in the Early Middle Ages, with Eidyn serving as one of the kingdom's districts. During this period, the Castle Rock site, thought to have been the stronghold of Din Eidyn, emerged as the kingdom's major centre.[4] The medieval poem Y Gododdin describes a war band from across the Brittonic world who gathered in Eidyn before a fateful raid; this may describe a historical event around AD 600.[5][6][7]

In 638, the Gododdin stronghold was besieged by forces loyal to King Oswald of Northumbria, and around this time control of Lothian passed to the Angles. Their influence continued for the next three centuries until around 950, when, during the reign of Indulf, son of Constantine II, the "burh" (fortress), named in the 10th-century Pictish Chronicle as oppidum Eden,[8] was abandoned to the Scots. It thenceforth remained, for the most part, under their jurisdiction.[9]

The royal burgh was founded by King David I in the early 12th century on land belonging to the Crown, though the date of its charter is unknown.[10] The first documentary evidence of the medieval burgh is a royal charter, c. 1124–1127, by King David I granting a toft in burgo meo de Edenesburg to the Priory of Dunfermline.[11] The shire of Edinburgh seems to have also been created in the reign of David I, possibly covering all of Lothian at first, but by 1305 the eastern and western parts of Lothian had become Haddingtonshire and Linlithgowshire, leaving Edinburgh as the county town of a shire covering the central part of Lothian, which was called Edinburghshire or Midlothian (the latter name being an informal, but commonly used, alternative until the county's name was legally changed in 1947).[12][13]

Edinburgh was largely under English control from 1291 to 1314 and from 1333 to 1341, during the Wars of Scottish Independence. When the English invaded Scotland in 1298, Edward I of England chose not to enter Edinburgh but passed by it with his army.[14]

In the middle of the 14th century, the French chronicler Jean Froissart described it as the capital of Scotland (c. 1365), and James III (1451–88) referred to it in the 15th century as "the principal burgh of our kingdom".[15] In 1482 James III "granted and perpetually confirmed to the said Provost, Bailies, Clerk, Council, and Community, and their successors, the office of Sheriff within the Burgh for ever, to be exercised by the Provost for the time as Sheriff, and by the Bailies for the time as Sheriffsdepute conjunctly and severally; with full power to hold Courts, to punish transgressors not only by banishment but by death, to appoint officers of Court, and to do everything else appertaining to the office of Sheriff; as also to apply to their own proper use the fines and escheats arising out of the exercise of the said office."[16] Despite being burnt by the English in 1544, Edinburgh continued to develop and grow,[17] and was at the centre of events in the 16th-century Scottish Reformation[18] and 17th-century Wars of the Covenant.[19] In 1582, Edinburgh's town council was given a royal charter by King James VI permitting the establishment of a university;[20] founded as Tounis College (Town's College), the institution developed into the University of Edinburgh, which contributed to Edinburgh's central intellectual role in subsequent centuries.[21]

17th century Edinburgh in the 17th century

Edinburgh in the 17th century Edinburgh, around 1690

Edinburgh, around 1690In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded to the English throne, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in a personal union known as the Union of the Crowns, though Scotland remained, in all other respects, a separate kingdom.[22] In 1638, King Charles I's attempt to introduce Anglican church forms in Scotland encountered stiff Presbyterian opposition culminating in the conflicts of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.[23] Subsequent Scottish support for Charles Stuart's restoration to the throne of England resulted in Edinburgh's occupation by Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth of England forces – the New Model Army – in 1650.[24]

In the 17th century, Edinburgh's boundaries were still defined by the city's defensive town walls. As a result, the city's growing population was accommodated by increasing the height of the houses. Buildings of 11 storeys or more were common,[25] and have been described as forerunners of the modern-day skyscraper.[26][27] Most of these old structures were replaced by the predominantly Victorian buildings seen in today's Old Town. In 1611 an act of parliament created the High Constables of Edinburgh to keep order in the city, thought to be the oldest statutory police force in the world.[28]

18th century A painting showing Edinburgh characters (based on John Kay's caricatures) behind St Giles' Cathedral in the late 18th century

A painting showing Edinburgh characters (based on John Kay's caricatures) behind St Giles' Cathedral in the late 18th centuryFollowing the Treaty of Union in 1706, the Parliaments of England and Scotland passed Acts of Union in 1706 and 1707 respectively, uniting the two kingdoms in the Kingdom of Great Britain effective from 1 May 1707.[29] As a consequence, the Parliament of Scotland merged with the Parliament of England to form the Parliament of Great Britain, which sat at Westminster in London. The Union was opposed by many Scots, resulting in riots in the city.[30]

By the first half of the 18th century, Edinburgh was described as one of Europe's most densely populated, overcrowded and unsanitary towns.[31][32] Visitors were struck by the fact that the social classes shared the same urban space, even inhabiting the same tenement buildings; although here a form of social segregation did prevail, whereby shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to occupy the cheaper-to-rent cellars and garrets, while the more well-to-do professional classes occupied the more expensive middle storeys.[33]

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly occupied by the Jacobite "Highland Army" before its march into England.[34] After its eventual defeat at Culloden, there followed a period of reprisals and pacification, largely directed at the rebellious clans.[35] In Edinburgh, the Town Council, keen to emulate London by initiating city improvements and expansion to the north of the castle,[36] reaffirmed its belief in the Union and loyalty to the Hanoverian monarch George III by its choice of names for the streets of the New Town: for example, Rose Street and Thistle Street; and for the royal family, George Street, Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and Princes Street (in honour of George's two sons).[37] The consistently geometric layout of the plan for the extension of Edinburgh was the result of a major competition in urban planning staged by the Town Council in 1766.[38]

In the second half of the century, the city was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment,[39] when thinkers like David Hume, Adam Smith, James Hutton and Joseph Black were familiar figures in its streets. Edinburgh became a major intellectual centre, earning it the nickname "Athens of the North" because of its many neo-classical buildings and reputation for learning, recalling ancient Athens.[40] In the 18th-century novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker by Tobias Smollett one character describes Edinburgh as a "hotbed of genius".[41] Edinburgh was also a major centre for the Scottish book trade. The highly successful London bookseller Andrew Millar was apprenticed there to James McEuen.[42]

From the 1770s onwards, the professional and business classes gradually deserted the Old Town in favour of the more elegant "one-family" residences of the New Town, a migration that changed the city's social character. According to the foremost historian of this development, "Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable heritages of old Edinburgh, and its disappearance was widely and properly lamented."[43]

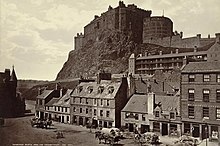

19th and 20th centuries Edinburgh Castle from the Grassmarket, photographed by George Washington Wilson circa 1875

Edinburgh Castle from the Grassmarket, photographed by George Washington Wilson circa 1875 Edinburgh, c. 1920

Edinburgh, c. 1920Despite an enduring myth to the contrary,[44] Edinburgh became an industrial centre[45] with its traditional industries of printing, brewing and distilling continuing to grow in the 19th century and joined by new industries such as rubber works, engineering works and others. By 1821, Edinburgh had been overtaken by Glasgow as Scotland's largest city.[46] The city centre between Princes Street and George Street became a major commercial and shopping district, a development partly stimulated by the arrival of railways in the 1840s. The Old Town became an increasingly dilapidated, overcrowded slum with high mortality rates.[47] Improvements carried out under Lord Provost William Chambers in the 1860s began the transformation of the area into the predominantly Victorian Old Town seen today.[48] More improvements followed in the early 20th century as a result of the work of Patrick Geddes,[49] but relative economic stagnation during the two world wars and beyond saw the Old Town deteriorate further before major slum clearance in the 1960s and 1970s began to reverse the process. University building developments which transformed the George Square and Potterrow areas proved highly controversial.[50]

Since the 1990s a new "financial district", including the Edinburgh International Conference Centre, has grown mainly on demolished railway property to the west of the castle, stretching into Fountainbridge, a run-down 19th-century industrial suburb which has undergone radical change since the 1980s with the demise of industrial and brewery premises. This ongoing development has enabled Edinburgh to maintain its place as the United Kingdom's second largest financial and administrative centre after London.[51][52] Financial services now account for a third of all commercial office space in the city.[53] The development of Edinburgh Park, a new business and technology park covering 38 acres (15 ha), 4 mi (6 km) west of the city centre, has also contributed to the District Council's strategy for the city's major economic regeneration.[53]

In 1998, the Scotland Act, which came into force the following year, established a devolved Scottish Parliament and Scottish Executive (renamed the Scottish Government since September 2007[54]). Both based in Edinburgh, they are responsible for governing Scotland while reserved matters such as defence, foreign affairs and some elements of income tax remain the responsibility of the Parliament of the United Kingdom in London.[55]

21st centuryIn 2022, Edinburgh was affected by the 2022 Scotland bin strikes.[56] In 2023, Edinburgh became the first capital city in Europe to sign the global Plant Based Treaty, which was introduced at COP26 in 2021 in Glasgow.[57] Green Party councillor Steve Burgess introduced the treaty. The Scottish Countryside Alliance and other farming groups called the treaty "anti-farming."[58]

Add new comment