Dunhuang () is a county-level city in northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Sachu (Dunhuang) was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road and is best known for the nearby Mogao Caves.

Dunhuang is situated in an oasis containing Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan (鳴沙山, meaning "Singing-Sand Mountain"), named after the sound of the wind whipping off the dunes, the singing sand phenomenon. Dunhuang commands a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and southern Siberia, and also controls the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which leads straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an) a...Read more

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Sachu (Dunhuang) was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road and is best known for the nearby Mogao Caves.

Dunhuang is situated in an oasis containing Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan (鳴沙山, meaning "Singing-Sand Mountain"), named after the sound of the wind whipping off the dunes, the singing sand phenomenon. Dunhuang commands a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and southern Siberia, and also controls the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which leads straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an) and Luoyang.

Administratively, the county-level city of Dunhuang is part of the prefecture-level city of Jiuquan. Historically, the city and/or its surrounding region has also been known by the names Shazhou (prefecture of sand) or Guazhou (prefecture of melons). In the modern era, the two alternative names have been assigned respectively to Shazhou zhen (Shazhou town) which serves as Dunhuang's seat of government, and to the neighboring Guazhou County.

The ruins of a Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) Chinese watchtower made of rammed earth at Dunhuang.

The ruins of a Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) Chinese watchtower made of rammed earth at Dunhuang.There is evidence of habitation in the area as early as 2,000 BC, possibly by people recorded as the Qiang in Chinese history. According to Zuo Zhuan and Book of the Later Han, the Dunhuang region was a part of the ancient Guazhou, which was known for its production of delicious melons.[1] Its name was also mentioned in relation to the homeland of the Yuezhi in the Records of the Grand Historian. Some have argued that this may refer to the unrelated toponym Dunhong – the archaeologist Lin Meicun has also suggested that Dunhuan may be a Chinese name for the Tukhara, a people widely believed to be a Central Asian offshoot of the Yuezhi.[2]

Warring States periodDuring the Warring States period, the inhabitants of Dunhuang included the Dayuezhi people, Wusun people, and Saizhong people (Chinese name for Scythians). As Dayuezhi became stronger, it absorbed the Qiang tribes.

Han dynastyBy the third century BC, the area became dominated by the Xiongnu, but came under Chinese rule during the Han dynasty after Emperor Wu defeated the Xiongnu in 121 BC.

Dunhuang was one of the four frontier garrison towns (along with Jiuquan, Zhangye and Wuwei) established by the Emperor Wu after the defeat of the Xiongnu, and the Chinese built fortifications at Dunhuang and sent settlers there. The name Dunhuang, meaning "Blazing Beacon", refers to the beacons lit to warn of attacks by marauding nomadic tribes. Dunhuang Commandery was probably established shortly after 104 BC.[3] Located in the western end of the Hexi Corridor near the historic junction of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, Dunhuang was a town of military importance.[4]

"The Great Wall was extended to Dunhuang, and a line of fortified beacon towers stretched westwards into the desert. By the second century AD Dunhuang had a population of more than 76,000 and was a key supply base for caravans that passed through the city: those setting out for the arduous trek across the desert loaded up with water and food supplies, and others arriving from the west gratefully looked upon the mirage-like sight of Dunhuang's walls, which signified safety and comfort. Dunhuang prospered on the heavy flow of traffic. The first Buddhist caves in the Dunhuang area were hewn in 353."[5]

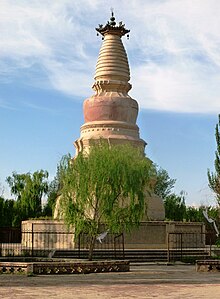

Sui dynasty and Tang dynasty White Horse Pagoda, Dunhuang

White Horse Pagoda, DunhuangDuring the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, it was the main stop of communication between ancient China and the rest of the world and a major hub of commerce of the Silk Road. Dunhuang was the intersection city of all three main silk routes (north, central, south) during this time.

From the West also came early Buddhist monks, who had arrived in China by the first century AD, and a sizable Buddhist community eventually developed in Dunhuang. The caves carved out by the monks, originally used for meditation, developed into a place of worship and pilgrimage called the Mogao Caves or "Caves of a Thousand Buddhas."[6] A number of Christian, Jewish, and Manichaean artifacts have also been found in the caves (see for example Jingjiao Documents), testimony to the wide variety of people who made their way along the Silk Road.

During the time of the Sixteen Kingdoms, Li Gao established the Western Liang here in 400 AD. In 405 the capital of the Western Liang was moved from Dunhuang to Jiuquan. In 421 the Western Liang was conquered by the Northern Liang.

Tang period (618–907) Buddhist sutra fragment from Dunhuang

Tang period (618–907) Buddhist sutra fragment from DunhuangAs a frontier town, Dunhuang was fought over and occupied at various times by non-Han people. After the fall of Han dynasty it came under the rule of various nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu during Northern Liang and the Turkic Tuoba during Northern Wei. The Tibetans occupied Dunhuang when the Tang Empire became weakened considerably after the An Lushan Rebellion; and even though it was later returned to Tang rule, it was under quasi-autonomous rule by the local general Zhang Yichao, who expelled the Tibetans in 848. After the fall of Tang, Zhang's family formed the Kingdom of Golden Mountain in 910,[7] but in 911 it came under the influence of the Uighurs. The Zhangs were succeeded by the Cao family, who formed alliances with the Uighurs and the Kingdom of Khotan.

Song dynastyDuring the Song dynasty, Dunhuang fell outside the Chinese borders. In 1036 the Tanguts who founded the Western Xia dynasty captured Dunhuang.[7] From the reconquest of 848 to about 1036 (i.e. era of the Guiyi Circuit), Dunhuang was a multicultural entrepot that contained one of the largest ethnic Sogdian communities in China following the An Lushan Rebellion. The Sogdians were Sinified to some extent and were bilingual in Chinese and Sogdian, and wrote their documents in Chinese characters, but horizontally from left to right instead of right to left in vertical lines, as Chinese was normally written at the time.[8]

Yuan dynastyDunhuang was conquered in 1227 by the Mongols, and became part of the Mongol Empire in the wake of Kublai Khan's conquest of China under the Yuan dynasty.

Ming dynastyDuring the Ming dynasty, China became a major sea power, conducting several voyages of exploration with sea routes for trade and cultural exchanges. Dunhuang went into a steep decline after the Chinese trade with the outside world became dominated by southern sea-routes, and the Silk Road was officially abandoned during the Ming dynasty. It was occupied again by the Tibetans c. 1516, and also came under the influence of the Chagatai Khanate in the early sixteenth century.[9]

Qing dynastyDunhuang was retaken by China two centuries later c. 1715 during the Qing dynasty, and the present-day city of Dunhuang was established east of the ruined old city in 1725.[10]

People's Republic of ChinaIn 1988, Dunhuang was elevated from county to county-level city status.[11] On March 31, 1995, Turpan and Dunhuang became sister cities.[12]

Dunhuang dance

Dunhuang danceToday, the site is an important tourist attraction and the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. A large number of manuscripts and artifacts retrieved at Dunhuang have been digitized and made publicly available via the International Dunhuang Project.[13] The spreading Kumtag Desert, the result of long-standing overgrazing of the surrounding land, has reached the edges of the city.[14]

In 2011 satellite images showing huge structures in the desert near Dunhuang surfaced online and caused a brief media stir.[15]

Add new comment