Uzbekistan

Context of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (UK: , US: ; Uzbek: Oʻzbekiston, Ўзбекистон, pronounced [ozbekiˈstɒn]; Russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzbek: Oʻzbekiston Respublikasi, Ўзбекистон Республикаси), is a doubly landlocked country located in Central Asia. It is surrounded by five landlocked countries: Kazakhstan to the north; Kyrgyzstan to the northeast; Tajikistan to the southeast; Afghanistan to the south; and Turkmenistan to the southwest. Its capital and largest city is Tashkent. Uzbekistan is part of the Turkic world, as well as a member of the Organization of Turkic States. The U...Read more

Uzbekistan (UK: , US: ; Uzbek: Oʻzbekiston, Ўзбекистон, pronounced [ozbekiˈstɒn]; Russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzbek: Oʻzbekiston Respublikasi, Ўзбекистон Республикаси), is a doubly landlocked country located in Central Asia. It is surrounded by five landlocked countries: Kazakhstan to the north; Kyrgyzstan to the northeast; Tajikistan to the southeast; Afghanistan to the south; and Turkmenistan to the southwest. Its capital and largest city is Tashkent. Uzbekistan is part of the Turkic world, as well as a member of the Organization of Turkic States. The Uzbek language is the majority-spoken language in Uzbekistan, while Russian is widely spoken and understood throughout the country. Tajik is also spoken as a minority language, predominantly in Samarkand and Bukhara. Islam is the predominant religion in Uzbekistan, most Uzbeks being Sunni Muslims.

The first recorded settlers in what is now Uzbekistan were Eastern Iranian nomads, known as Scythians, who founded kingdoms in Khwarazm, Bactria, and Sogdia in the 8th–6th centuries BC, as well as Fergana and Margiana in the 3rd century BC – 6th century AD. The area was incorporated into the Iranian Achaemenid Empire and, after a period of Macedonian rule, was ruled by the Iranian Parthian Empire and later by the Sasanian Empire, until the Muslim conquest of Persia in the seventh century.

The early Muslim conquests and the subsequent Samanid Empire converted most of the people, including the local ruling classes, into adherents of Islam. During this period, cities such as Samarkand, Khiva, and Bukhara began to grow rich from the Silk Road, and became a center of the Islamic Golden Age, with figures such as Muhammad al-Bukhari, Al-Tirmidhi, al Khwarizmi, al-Biruni, Avicenna, and Omar Khayyam.

The local Khwarazmian dynasty was destroyed by the Mongol invasion in the 13th century, leading to a dominance by Turkic peoples. Timur (Tamerlane), who in the 14th century established the Timurid Empire, was from Shahrisabz. Its capital was Samarkand, which became a centre of science under the rule of Ulugh Beg, giving birth to the Timurid Renaissance.

The territories of the Timurid dynasty were conquered by Uzbek Shaybanids in the 16th century, moving the centre of power to Bukhara. The region was split into three states: the Khanate of Khiva, Khanate of Kokand, and Emirate of Bukhara. Conquests by Emperor Babur towards the east led to the foundation of the Mughal Empire in India.

All of Central Asia was gradually incorporated into the Russian Empire during the 19th century, with Tashkent becoming the political center of Russian Turkestan. In 1924, national delimitation created the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic as a republic of the Soviet Union. Shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it declared independence as the Republic of Uzbekistan on 31 August 1991.

Uzbekistan is a secular state, with a presidential constitutional government in place. Uzbekistan comprises 12 regions (vilayats), Tashkent City, and one autonomous republic, Karakalpakstan. While non-governmental human rights organisations have defined Uzbekistan as "an authoritarian state with limited civil rights", significant reforms under Uzbekistan's second president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, have been made following the death of the first president, Islam Karimov. Owing to these reforms, relations with the neighbouring countries of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan have drastically improved. A United Nations report of 2020 found much progress toward achieving the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.

The Uzbek economy is in a gradual transition to the market economy, with foreign trade policy being based on import substitution. In September 2017, the country's currency became fully convertible at market rates. Uzbekistan is a major producer and exporter of cotton. With the gigantic power-generation facilities from the Soviet era and an ample supply of natural gas, Uzbekistan has become the largest electricity producer in Central Asia.

From 2018 to 2021, the republic received a BB- sovereign credit rating by both Standard and Poor (S&P) and Fitch Ratings. The Brookings Institution described Uzbekistan as having large liquid assets, high economic growth, low public debt, and a low GDP per capita. Uzbekistan is a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), United Nations and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

More about Uzbekistan

- Currency Uzbekistani soʻm

- Calling code +998

- Internet domain .uz

- Mains voltage 220V/50Hz

- Democracy index 2.12

- Population 34915100

- Area 448978

- Driving side right

- Read less

Female statuette wearing the kaunakes. Chlorite and limestone, Bactria, beginning of the second millennium BC

Female statuette wearing the kaunakes. Chlorite and limestone, Bactria, beginning of the second millennium BC Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus. Mosaic in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus. Mosaic in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.The first people known to have inhabited Central Asia were Scythians who came from the northern grasslands of what is now Uzbekistan, sometime in the first millennium BC; when these nomads settled in the region they built an extensive irrigation system along the rivers.[1] At this time, cities such as Bukhoro (Bukhara) and Samarqand (Samarkand) emerged as centres of government and high culture.[1] By the fifth century BC, the Bactrian, Sogdian, and Tokharian states dominated the region.[1]

As East Asia began to develop its silk trade with the West, Persian cities took advantage of this commerce by becoming centres of trade. Using an extensive network of cities and rural settlements in the province of Transoxiana, and further east in what is today Xinjiang, the Sogdian intermediaries became the wealthiest of these Iranian merchants. As a result of this trade on what became known as the Silk Route, Bukhara and Samarkand eventually became extremely wealthy cities, and at times Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) was one of the most influential and powerful Persian provinces of antiquity.[1]

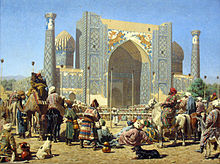

Triumphant crowd at Registan, Sher-Dor Madrasah. The Emir of Bukhara viewing the severed heads of Russian soldiers on poles. Painting by Vasily Vereshchagin (1872). Russian troops taking Samarkand in 1868, by Nikolay Karazin.

Russian troops taking Samarkand in 1868, by Nikolay Karazin.In 327 BC, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire provinces of Sogdiana and Bactria, which contained the territories of modern Uzbekistan. Popular resistance to the conquest was fierce, causing Alexander's army to be bogged down in the region that became the northern part of the Macedonian Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. The kingdom was replaced with the Yuezhi-dominated Kushan Empire in the first century BC. For many centuries thereafter the region of Uzbekistan was ruled by the Persian empires, including the Parthian and Sassanid Empires, as well as by other empires, for example, those formed by the Turko-Persian Hephthalite and Turkic Gokturk peoples.

The Muslim conquests from the seventh century onward saw the Arabs bring Islam to Uzbekistan. In the same period, Islam began to take root among the nomadic Turkic peoples.

In the eighth century, Transoxiana, the territory between the Amudarya and Syrdarya rivers, was conquered by the Arabs (Qutayba ibn Muslim), becoming a focal point soon after the Islamic Golden Age.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, Transoxiana was brought into the Samanid State. Later, it saw the incursion of the Turkic-ruled Karakhanids, as well as the Seljuks (Sultan Sanjar) and Kara-Khitans.[2]

The Mongol conquest under Genghis Khan during the 13th century brought change to the region. The Mongol invasion of Central Asia led to the displacement of some of the Iranian-speaking people of the region, their culture and heritage being superseded by that of the Mongolian-Turkic peoples who came thereafter. The invasions of Bukhara, Samarkand, Urgench and others resulted in mass murders and unprecedented destruction, which saw parts of Khwarezmia being completely razed.[3]

Following the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, his empire was divided among his four sons and his family members. Despite the potential for serious fragmentation, there was an orderly succession for several generations, and control of most of Transoxiana stayed in the hands of the direct descendants of Chagatai Khan, the second son of Genghis Khan. Orderly succession, prosperity, and internal peace prevailed in the Chaghatai lands, and the Mongol Empire as a whole remained a strong and united kingdom, the Golden Horde.[4]

Two Sart men and two Sart boys in Samarkand, c. 1910

Two Sart men and two Sart boys in Samarkand, c. 1910After the decline of the Golden Horde, Khwarezm was briefly ruled by the Sufi Dynasty until Timur's conquest of it in 1388.[5] Sufids rules Khwarezm as vassals of alternatively Timurids, Golden Horde and the Khanate of Bukhara until Persian occupation in 1510.

In the early 14th century, however, as the empire began to break up into its constituent parts, the Chaghatai territory was disrupted as the princes of various tribal groups competed for influence. One tribal chieftain, Timur (Tamerlane),[6] emerged from these struggles in the 1380s as the dominant force in Transoxiana. Although he was not a descendant of Genghis Khan, Timur became the de facto ruler of Transoxiana and proceeded to conquer all of western Central Asia, Iran, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the southern steppe region north of the Aral Sea. He also invaded Russia before dying during an invasion of China in 1405.[4] Timur was also known for his extreme brutality and his conquests were accompanied by genocidal massacres in the cities he occupied.[7]

Timur initiated the last flowering of Transoxiana by gathering together numerous artisans and scholars from the vast lands he had conquered into his capital, Samarkand, thus imbuing his empire with a rich Perso-Islamic culture. During his reign and the reigns of his immediate descendants, a wide range of religious and palatial construction masterpieces were undertaken in Samarkand and other population centres.[8] Amir Timur initiated an exchange of medical discoveries and patronised physicians, scientists and artists from the neighbouring regions such as India;[9] His grandson Ulugh Beg was one of the world's first great astronomers. It was during the Timurid dynasty that Turkic, in the form of the Chaghatai dialect, became a literary language in its own right in Transoxiana, although the Timurids were Persianate in culture. The greatest Chaghataid writer, Ali-Shir Nava'i, was active in the city of Herat (now in northwestern Afghanistan) in the second half of the 15th century.[4]

The Timurid state quickly split in half after the death of Timur. The chronic internal fighting of the Timurids attracted the attention of the Uzbek nomadic tribes living to the north of the Aral Sea. In 1501, the Uzbek forces began a wholesale invasion of Transoxiana.[4] The slave trade in the Emirate of Bukhara became prominent and was firmly established at this time.[10] Before the arrival of the Russians, present-day Uzbekistan was divided between the Emirate of Bukhara and the khanates of Khiva and Kokand.

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire began to expand and spread into Central Asia. There were 210,306 Russians living in Uzbekistan in 1912.[11] The "Great Game" period is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. A second, less intensive phase followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. At the start of the 19th century, there were some 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi) separating British India and the outlying regions of Tsarist Russia. Much of the land between was unmapped. In the early 1890s, Sven Hedin passed through Uzbekistan, during his first expedition.

By the beginning of 1920, Central Asia was firmly in the hands of Russia and, despite some early resistance to the Bolsheviks, Uzbekistan and the rest of Central Asia became a part of the Soviet Union. On 27 October 1924 the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was created. From 1941 to 1945, during World War II, 1,433,230 people from Uzbekistan fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany. A number also fought on the German side. As many as 263,005 Uzbek soldiers died in the battlefields of the Eastern Front, and 32,670 went missing in action.[12]

On 20 June 1990, Uzbekistan declared its state sovereignty. On 31 August 1991, Uzbekistan declared independence after the failed coup attempt in Moscow. 1 September was proclaimed National Independence Day. The Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December of that year. Islam Karimov, previously first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan since 1989, was elected president of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1990. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, he was elected president of independent Uzbekistan.[13] An authoritarian ruler, Karimov died in September 2016.[14] He was replaced by his long-time Prime Minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, on 14 December of the same year.[15] On 6 November 2021, Mirziyoyev was sworn into his second term in office, after gaining a landslide victory in presidential election.[16][17]

^ a b c d This section incorporates text from the following source, which is in the public domain: Lubin, Nancy (1997). "Uzbekistan", chapter 5 in: Glenn E. Curtis (Ed.), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan: Country Studies. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844409383. pp. 375–468: Early History, pp. 385–386. ^ Davidovich, E. A. (1998). "The Karakhanids; Chapter 6 The Karakhanids". In C.E. Bosworth (ed.). History of Civilisations of Central Asia. Vol. 4 part I. UNESCO Publishing. pp. 119–144. ISBN 92-3-103467-7. ^ Central Asian world cities (XI – XIII century). faculty.washington.edu ^ a b c d This section incorporates text from the following source, which is in the public domain: Lubin, Nancy (1997). "Uzbekistan", chapter 5 in: Glenn E. Curtis (Ed.), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan: Country Studies Archived 30 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844409383. p. 375–468; here: "The Rule of Timur ", p. 389–390. ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia (Vol. 4, Part 1). Motilal Banarsidass. 1992. p. 328. ISBN 978-81-208-1595-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. ^ Sicker, Martin (2000) The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna Archived 12 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 154. ISBN 0-275-96892-8 ^ Totten, Samuel and Bartrop, Paul Robert (2008) Dictionary of Genocide: A-L Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, ABC-CLIO, p. 422, ISBN 0313346429 ^ Forbes, Andrew, & Henley, David: Timur's Legacy: The Architecture of Bukhara and Samarkand Archived 24 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine (CPA Media). ^ Medical Links between India & Uzbekistan in Medieval Times by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Historical and Cultural Links between India & Uzbekistan, Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, Patna, 1996. pp. 353–381. ^ "Adventure in the East". Time. 6 April 1959. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011. ^ Shlapentokh, Vladimir; Sendich, Munir; Payin, Emil (1994) The New Russian Diaspora: Russian Minorities in the Former Soviet Republics Archived 8 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. M.E. Sharpe. p. 108. ISBN 1-56324-335-0. ^ Chahryar Adle, Madhavan K. Palat, Anara Tabyshalieva (2005). "Towards the Contemporary Period: From the Mid-nineteenth to the End of the Twentieth Century Archived 29 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine". UNESCO. p.232. ISBN 9231039857 ^ "Islam Karimov | president of Uzbekistan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 July 2021. ^ "Obituary: Uzbekistan President Islam Karimov". BBC News. 2 October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. ^ "Uzbekistan elects Shavkat Mirziyoyev as president". TheGuardian.com. 5 December 2016. ^ "Uzbek president secures second term in landslide election victory". www.aljazeera.com. 25 October 2021. ^ "Uzbek president pledges constitutional reform | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. 7 November 2021.

- Stay safeUzbek police in Samarkand

The areas of Uzbekistan bordering Afghanistan should be avoided for all but essential travel. Extreme caution should also be exercised in areas of the Ferghana Valley bordering Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. There have been a number of security incidents in this region, as well as several exchanges of gunfire across the Uzbek/Kyrgyz border. Some border areas are also mined. Travellers should therefore avoid these areas and cross only at authorized border crossing points.

For the most part, Uzbekistan is generally safe for visitors, perhaps the by-product of a police state. There are many anecdotal (and a significant number of documented) reports of an increase in street crime, especially in the larger towns, particularly Tashkent. This includes an increase in violent crime. Information on crime is largely available only through word of mouth - both among locals and through the expat community - as the state-controlled press rarely, if ever, reports street crime. As economic conditions in Uzbekistan continue to deteriorate, street crime is increasing.

Normal precautions should be taken, as one would in virtually any country. Especially in the cities (few travellers will spend much time overnight in the small villages), be careful after dark, avoid unlighted areas, and don't walk alone. Even during the day, refrain from openly showing significant amounts of cash. Men should keep wallets in a front pocket and women should keep purses in front of them with a strap around an arm. Avoid wearing flashy or valuable jewellery which can easily be snatched.

...Read moreStay safeRead lessUzbek police in SamarkandThe areas of Uzbekistan bordering Afghanistan should be avoided for all but essential travel. Extreme caution should also be exercised in areas of the Ferghana Valley bordering Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. There have been a number of security incidents in this region, as well as several exchanges of gunfire across the Uzbek/Kyrgyz border. Some border areas are also mined. Travellers should therefore avoid these areas and cross only at authorized border crossing points.

For the most part, Uzbekistan is generally safe for visitors, perhaps the by-product of a police state. There are many anecdotal (and a significant number of documented) reports of an increase in street crime, especially in the larger towns, particularly Tashkent. This includes an increase in violent crime. Information on crime is largely available only through word of mouth - both among locals and through the expat community - as the state-controlled press rarely, if ever, reports street crime. As economic conditions in Uzbekistan continue to deteriorate, street crime is increasing.

Normal precautions should be taken, as one would in virtually any country. Especially in the cities (few travellers will spend much time overnight in the small villages), be careful after dark, avoid unlighted areas, and don't walk alone. Even during the day, refrain from openly showing significant amounts of cash. Men should keep wallets in a front pocket and women should keep purses in front of them with a strap around an arm. Avoid wearing flashy or valuable jewellery which can easily be snatched.

Scams are not unheard of. One of the most common (and one that is not limited to Uzbekistan) involves a stranger coming up to the victim and saying they have found cash lying on the street. They will then try to enlist you in a complicated scheme that will result in you "splitting" the cash - of course only after you have put up some of your own. The entire scenario is ludicrous, but apparently enough greedy foreigners fall for it that it continues. If someone comes up to you with the "found cash" routine, tell them straight away that you are not interested (in whatever language you choose) and walk away.

Also beware of locals you don't know who offer to show you the "night life." This should be completely avoided, though some visitors seem to leave their common sense at home.

While all of these precautions should be observed during travel virtually anywhere in the world, for some reason many tourists in Uzbekistan seem to lower their guard. They should not.

It is also possible that you will be asked by police (Militsiya) for documents. This doesn't happen often, but it can, and they have a legal right to do so. By law, you should carry your passport and visa with you in Uzbekistan, though in practice, it is better to make a color scan of the first two pages of your passport and your Uzbek visa before you arrive. Carry the colour copies with you when you're walking around, and keep the original documents in the hotel safe. The scanned documents will almost always suffice. If not, make it clear to the Militsiya officer that he will have to come to your hotel to see the originals. Unless they have something out of the norm in mind (such as a bribe) they will almost always give you a big smile and tell you to go along. Always be polite with the Militsiya, but also be firm. While almost all of them take bribes, they take them from locals. For the most part, they understand that going too far with a foreigner will only cause them problems, especially if the foreigner is neither being abusive nor quaking with fear.

One note about locals offering to show you around: It is common for younger Uzbeks (usually male) who speak English to try and "meet" foreigners at local hotels and offer to serve as interpreters and guides. This is done in daylight and in the open, often in or near some of the smaller but better hotels. This can be rewarding for both the local and the visitor. The local is usually trying to improve their English or French (occasionally other languages, but usually English) and to make a few dollars/euros. If you are approached by a clean-cut person offering such services, and you are interested, question them about their background, what they are proposing to do for you and how much they want to charge you (anywhere between $10-$25 a day is realistic depending on their services and how long they spend with you). Most of the legitimate offers will be from young people who have studied in the West on exchange programs and/or studied at the University of World Diplomacy and/or Languages in Tashkent. If everything seems to fit, their language skills are good and they seem eager and polite, but not pushy, you may want to consider this. They should offer to show you museums, historical sites, cafés, bazaars, cultural advice, generally how to get around, etc. They should ask you what you want to see and/or do. Often this works out well. However, for your and their protection, do not attempt to engage in political discussions of any type.

Again, if they are proposing "night life" (or related) services, do NOT take up their offers.