Namibia

Context of Namibia

Namibia ( (listen), ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border Zimbabwe, less than 200 metres (660 feet) of the Botswanan right bank of the Zambezi River separates the two countries. Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations (UN), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union (AU) and the Commonwealth of Nations.

The driest country in sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia has been inhabited since pre-historic times by the San, Damara and Nama people. Around the 14th century, immigrating Ban...Read more

Namibia ( (listen), ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border Zimbabwe, less than 200 metres (660 feet) of the Botswanan right bank of the Zambezi River separates the two countries. Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations (UN), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union (AU) and the Commonwealth of Nations.

The driest country in sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia has been inhabited since pre-historic times by the San, Damara and Nama people. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu peoples arrived as part of the Bantu expansion. Since then, the Bantu groups, the largest being the Ovambo, have dominated the population of the country; since the late 19th century, they have constituted a majority. Today Namibia is one of the least densely populated countries in the world.

It has a population of 2.55 million people and is a stable multi-party parliamentary democracy. Agriculture, tourism and the mining industry – including mining for gem diamonds, uranium, gold, silver and base metals – form the basis of its economy, while the manufacturing sector is comparatively small.

In 1884, the German Empire established rule over most of the territory, forming a colony known as German South West Africa. Between 1904 and 1908, it perpetrated a genocide against the Herero and Nama people. German rule ended in 1915 with a defeat by South African forces. In 1920, after the end of World War I, the League of Nations mandated administration of the colony to South Africa. As mandatory power, South Africa imposed its laws, including racial classifications and rules. From 1948, with the National Party elected to power, this included South Africa applying apartheid to what was then known as South West Africa. In the later 20th century, uprisings and demands for political representation by native African political activists seeking independence resulted in the UN assuming direct responsibility over the territory in 1966, but the country of South Africa maintained de facto rule. In 1973, the UN recognised the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) as the official representative of the Namibian people. Following continued guerrilla warfare, Namibia obtained independence in 1990. However, Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands remained under South African control until 1994.

More about Namibia

- Currency Namibian dollar

- Calling code +264

- Internet domain .na

- Mains voltage 220V/50Hz

- Democracy index 6.52

- Population 2533794

- Area 825615

- Driving side left

- Etymology

The name of the country is derived from the Namib desert, the oldest desert in the world.[1] The name Namib itself is of Nama origin and means "vast place". That word for the country was chosen by Mburumba Kerina, who originally proposed the name the "Republic of Namib".[2] Before its independence in 1990, the area was known first as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika), then as South West Africa, reflecting the colonial occupation by the Germans and South Africans.

...Read moreEtymologyRead lessThe name of the country is derived from the Namib desert, the oldest desert in the world.[1] The name Namib itself is of Nama origin and means "vast place". That word for the country was chosen by Mburumba Kerina, who originally proposed the name the "Republic of Namib".[2] Before its independence in 1990, the area was known first as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika), then as South West Africa, reflecting the colonial occupation by the Germans and South Africans.

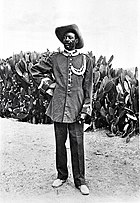

Pre-colonial period San people are Namibia's oldest indigenous inhabitants.

San people are Namibia's oldest indigenous inhabitants.The dry lands of Namibia have been inhabited since prehistoric times by the San, Damara, and Nama. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu people began to arrive during the Bantu expansion from central Africa.[3]

From the late 18th century onward, Oorlam people from Cape Colony crossed the Orange River and moved into the area that today is southern Namibia.[4] Their encounters with the nomadic Nama tribes were largely peaceful. They received the missionaries accompanying the Oorlam very well,[5] granting them the right to use waterholes and grazing against an annual payment.[6] On their way further north, however, the Oorlam encountered clans of the OvaHerero at Windhoek, Gobabis, and Okahandja, who resisted their encroachment. The Nama-Herero War broke out in 1880, with hostilities ebbing only after the German Empire deployed troops to the contested places and cemented the status quo among the Nama, Oorlam, and Herero.[7]

In 1878, the Cape of Good Hope, then a British colony, annexed the port of Walvis Bay and the offshore Penguin Islands; these became an integral part of the new Union of South Africa at its creation in 1910.

The first Europeans to disembark and explore the region were the Portuguese navigators Diogo Cão in 1485[8] and Bartolomeu Dias in 1486, but the Portuguese did not try to claim the area. Like most of the interior of Sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia was not extensively explored by Europeans until the 19th century. At that time traders and settlers came principally from Germany and Sweden. In 1870, Finnish missionaries came to the northern part of Namibia to spread the Lutheran religion among the Ovambo and Kavango people.[9] In the late 19th century, Dorsland Trekkers crossed the area on their way from the Transvaal to Angola. Some of them settled in Namibia instead of continuing their journey.

German rule German church and monument to colonists in Windhoek, Namibia.

German church and monument to colonists in Windhoek, Namibia.

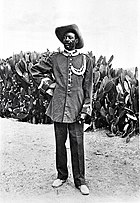

Hendrik Witbooi (left) and Samuel Maharero (right) were prominent leaders against German colonial rule.

Hendrik Witbooi (left) and Samuel Maharero (right) were prominent leaders against German colonial rule.Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under Otto von Bismarck to forestall perceived British encroachment and was known as German South West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika).[10] The Palgrave Commission by the British governor in Cape Town determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of Walvis Bay was worth occupying and thus annexed it to the Cape province of British South Africa.

From 1904 to 1907, the Herero and the Namaqua took up arms against brutal German colonialism. In a calculated punitive action by the German occupiers, government officials ordered the extinction of the natives in the OvaHerero and Namaqua genocide. In what has been called the "first genocide of the 20th century",[11] the Germans systematically killed 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Herero (about 80% of the population).[12][13] The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, racial segregation, and discrimination in a system that in many ways foreshadowed the apartheid established by South Africa in 1948.

Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which under South African rule after 1949 were turned into "homelands" (Bantustans). Some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model for the Nazis in the Holocaust.[14] The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.[15] The German minister for aid development apologised for the Namibian genocide in 2004, however, the German government distanced itself from this apology.[16][17]

South African mandateDuring World War I, South African troops under General Louis Botha occupied the territory and deposed the German colonial administration. The end of the war and the Treaty of Versailles resulted in South West Africa remaining a possession of South Africa, at first as a League of Nations mandate, until 1990.[18] The mandate system was formed as a compromise between those who advocated for an Allied annexation of former German and Ottoman territories and a proposition put forward by those who wished to grant them to an international trusteeship until they could govern themselves.[18] It permitted the South African government to administer South West Africa until that territory's inhabitants were prepared for political self-determination.[19] South Africa interpreted the mandate as a veiled annexation and made no attempt to prepare South West Africa for future autonomy.[19]

As a result of the Conference on International Organization in 1945, the League of Nations was formally superseded by the United Nations (UN) and former League mandates by a trusteeship system. Article 77 of the United Nations Charter stated that UN trusteeship "shall apply...to territories now held under mandate"; furthermore, it would "be a matter of subsequent agreement as to which territories in the foregoing territories will be brought under the trusteeship system and under what terms".[20] The UN requested all former League of Nations mandates be surrendered to its Trusteeship Council in anticipation of their independence.[20] South Africa declined to do so and instead requested permission from the UN to formally annex South West Africa, for which it received considerable criticism.[20] When the UN General Assembly rejected this proposal, South Africa dismissed its opinion and began solidifying control of the territory.[20] The UN Generally Assembly and Security Council responded by referring the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which held a number of discussions on the legality of South African rule between 1949 and 1966.[21]

Map depicting the Police Zone (in tan) and tribal homelands (in red) as they existed in 1978. Self-governing tribal homelands appear as tan with red stripes.

Map depicting the Police Zone (in tan) and tribal homelands (in red) as they existed in 1978. Self-governing tribal homelands appear as tan with red stripes. Foreign Observer identification badge issued during the 1989 Namibian election

Foreign Observer identification badge issued during the 1989 Namibian electionSouth Africa began imposing apartheid, its codified system of racial segregation and discrimination, on South West Africa during the late 1940s.[22] Black South West Africans were subject to pass laws, curfews, and a host of residential regulations that restricted their movement.[22] Development was concentrated in the southern region of the territory adjacent to South Africa, known as the "Police Zone", where most of the major settlements and commercial economic activity were located.[23] Outside the Police Zone, indigenous peoples were restricted to theoretically self-governing tribal homelands.[23]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the accelerated decolonisation of Africa and mounting pressure on the remaining colonial powers to grant their colonies self-determination resulted in the formation of nascent nationalist parties in South West Africa.[24] Movements such as the South West African National Union (SWANU) and the South West African People's Organisation advocated for the formal termination of South Africa's mandate and independence for the territory.[24] In 1966, following the ICJ's controversial ruling that it had no legal standing to consider the question of South African rule, SWAPO launched an armed insurgency that escalated into part of a wider regional conflict known as the South African Border War.[25]

IndependenceAs SWAPO's insurgency intensified, South Africa's case for annexation in the international community continued to decline.[26] The UN declared that South Africa had failed in its obligations to ensure the moral and material well-being of South West Africa's indigenous inhabitants, and had thus disavowed its own mandate.[27] On 12 June 1968, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming that, in accordance with the desires of its people, South West Africa be renamed Namibia.[27] United Nations Security Council Resolution 269, adopted in August 1969, declared South Africa's continued occupation of Namibia illegal.[27][28] In recognition of this landmark decision, SWAPO's armed wing was renamed the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN).[29]

Namibia became one of several flashpoints for Cold War proxy conflicts in southern Africa during the latter years of the PLAN insurgency.[30] The insurgents sought out weapons and sent recruits to the Soviet Union for military training.[31] As the PLAN war effort gained momentum, the Soviet Union and other sympathetic states such as Cuba continued to increase their support, deploying advisers to train the insurgents directly as well as supplying more weapons and ammunition.[32] SWAPO's leadership, dependent on Soviet, Angolan, and Cuban military aid, positioned the movement firmly within the socialist bloc by 1975.[33] This practical alliance reinforced the external perception of SWAPO as a Soviet proxy, which dominated Cold War rhetoric in South Africa and the United States.[23] For its part, the Soviet Union supported SWAPO partly because it viewed South Africa as a regional Western ally.[34]

South African troops patrol the border region for PLAN insurgents, 1980s.

South African troops patrol the border region for PLAN insurgents, 1980s.Growing war weariness and the reduction of tensions between the superpowers compelled South Africa, Angola, and Cuba to accede to the Tripartite Accord, under pressure from both the Soviet Union and the United States.[35] South Africa accepted Namibian independence in exchange for Cuban military withdrawal from the region and an Angolan commitment to cease all aid to PLAN.[36] PLAN and South Africa adopted an informal ceasefire in August 1988, and a United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) was formed to monitor the Namibian peace process and supervise the return of refugees.[37] The ceasefire was broken after PLAN made a final incursion into the territory, possibly as a result of misunderstanding UNTAG's directives, in March 1989.[38] A new ceasefire was later imposed with the condition that the insurgents were to be confined to their external bases in Angola until they could be disarmed and demobilised by UNTAG.[37][39]

By the end of the 11-month transition period, the last South African troops had been withdrawn from Namibia, all political prisoners granted amnesty, racially discriminatory legislation repealed, and 42,000 Namibian refugees returned to their homes.[33] Just over 97% of eligible voters participated in the country's first parliamentary elections held under a universal franchise.[40] The United Nations plan included oversight by foreign election observers in an effort to ensure a free and fair election. SWAPO won a plurality of seats in the Constituent Assembly with 57% of the popular vote.[40] This gave the party 41 seats, but not a two-thirds majority, which would have enabled it to draft the constitution on its own.[40]

The Namibian Constitution was adopted in February 1990. It incorporated protection for human rights and compensation for state expropriations of private property and established an independent judiciary, legislature, and an executive presidency (the constituent assembly became the national assembly). The country officially became independent on 21 March 1990.[41][9] Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia at a ceremony attended by Nelson Mandela of South Africa (who had been released from prison the previous month) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state.[42] In 1994, shortly before the first multiracial elections in South Africa, that country ceded Walvis Bay to Namibia.[43]

After independenceSince independence Namibia has completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to parliamentary democracy. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although the SWAPO has won every election since independence.[44] The transition from the 15-year rule of President Nujoma to his successor Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2005 went smoothly.[45]

Since independence, the Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation. It issued an amnesty for those who fought on either side during the liberation war. The civil war in Angola spilled over and adversely affected Namibians living in the north of the country. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force (NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) contingent.

In 1999, the national government quashed a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi Strip.[45] The Caprivi conflict was initiated by the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA), a rebel group led by Mishake Muyongo. It wanted the Caprivi Strip to secede and form its own society.

In December 2014, Prime Minister Hage Geingob, the candidate of ruling SWAPO, won the presidential elections, taking 87% of the vote. His predecessor, President Hifikepunye Pohamba, also of SWAPO, had served the maximum two terms allowed by the constitution.[46] In December 2019, President Hage Geingob was re-elected for a second term, taking 56.3% of the vote.[47]

^ Spriggs, A. (2001) "Africa: Namibia". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. ^ "The Man Who Named Namibia- Mburumba Kerina". The Namibian. Retrieved 15 June 2021. ^ Belda, Pascal (May 2007). Namibia. MTH Multimedia S.L. ISBN 978-84-935202-1-2. ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, A". Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2010. ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Warmbad becomes two hundred years". Klausdierks.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2010. ^ Vedder 1997, p. 177. ^ Vedder 1997, p. 659. ^ Observador. "Padrão português com 500 anos foi roubado da Namíbia no século XIX. Vai ser devolvido". Observador (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 7 December 2020. ^ a b Cite error: The named reference finnish-mission was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ "German South West Africa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 April 2008. ^ David Olusoga (18 April 2015). "Dear Pope Francis, Namibia was the 20th century's first genocide". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 November 2015. ^ Drechsler, Horst (1980). The actual number of deaths in the limited number of battles with the Germany Schutztruppe (expeditionary force) were limited; most of the deaths occurred after fighting had ended. The German military governor Lothar von Trotha issued an explicit extermination order, and many Herero died of disease and abuse in detention camps after being taken from their land. A substantial minority of Herero crossed the Kalahari desert into the British colony of Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana), where a small community continues to live in western Botswana near to border with Namibia. Let us die fighting, originally published (1966) under the title Südwestafrika unter deutscher Kolonialherrschaft. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ^ Cite error: The named reference Adhikari was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Cite error: The named reference Madley was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Reinhart Kössler and Henning Melber, "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908," ("Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa, 1904–08") Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust 2004: 37–75 ^ Andrew Meldrum (15 August 2004). "German minister says sorry for genocide in Namibia". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2018. ^ [Völkermord an Herero und Nama: Abkommen zwischen Deutschland und Namibia "German minister says sorry for genocide in Namibia"]. bpb. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2023. {{cite web}}: Check |url= value (help) ^ a b Rajagopal, Balakrishnan (2003). International Law from Below: Development, Social Movements and Third World Resistance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–68. ISBN 978-0521016711. ^ a b Louis, William Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. London: I.B. Tauris & Company, Ltd. pp. 251–261. ISBN 978-1845113476. ^ a b c d Vandenbosch, Amry (1970). South Africa and the World: The Foreign Policy of Apartheid. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 207–224. ISBN 978-0813164946. ^ First, Ruth (1963). Segal, Ronald (ed.). South West Africa. Baltimore: Penguin Books, Incorporated. pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-0844620619. ^ a b Crawford, Neta (2002). Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–336. ISBN 978-0521002790. ^ a b c Herbstein, Denis; Evenson, John (1989). The Devils Are Among Us: The War for Namibia. London: Zed Books Ltd. pp. 14–23. ISBN 978-0862328962. ^ a b Müller, Johann Alexander (2012). The Inevitable Pipeline Into Exile. Botswana's Role in the Namibian Liberation Struggle. Basel, Switzerland: Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Center and Southern Africa Library. pp. 36–41. ISBN 978-3905758290. ^ Kangumu, Bennett (2011). Contesting Caprivi: A History of Colonial Isolation and Regional Nationalism in Namibia. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Center and Southern Africa Library. pp. 143–153. ISBN 978-3905758221. ^ Dobell, Lauren (1998). Swapo's Struggle for Namibia, 1960–1991: War by Other Means. Basel: P. Schlettwein Publishing Switzerland. pp. 27–39. ISBN 978-3908193029. ^ a b c Yusuf, Abdulqawi (1994). African Yearbook of International Law, Volume I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 16–34. ISBN 978-0-7923-2718-9. ^ Peter, Abbott; Helmoed-Romer Heitman; Paul Hannon (1991). Modern African Wars (3): South-West Africa. Osprey Publishing. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-1-85532-122-9.[permanent dead link] ^ Williams, Christian (October 2015). National Liberation in Postcolonial Southern Africa: A Historical Ethnography of SWAPO's Exile Camps. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–89. ISBN 978-1107099340. ^ Hughes, Geraint (2014). My Enemy's Enemy: Proxy Warfare in International Politics. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 73–86. ISBN 978-1845196271. ^ Bertram, Christoph (1980). Prospects of Soviet Power in the 1980s. Basingstoke: Palgrave Books. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-1349052592. ^ Vanneman, Peter (1990). Soviet Strategy in Southern Africa: Gorbachev's Pragmatic Approach. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 41–57. ISBN 978-0817989026. ^ a b Dreyer, Ronald (1994). Namibia and Southern Africa: Regional Dynamics of Decolonization, 1945-90. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 73–87, 100–116, 192. ISBN 978-0710304711. ^ Shultz, Richard (1988). Soviet Union and Revolutionary Warfare: Principles, Practices, and Regional Comparisons. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 121–123, 140–145. ISBN 978-0817987114. ^ Sechaba, Tsepo; Ellis, Stephen (1992). Comrades Against Apartheid: The ANC & the South African Communist Party in Exile. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 184–187. ISBN 978-0253210623. ^ James III, W. Martin (2011) [1992]. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola: 1974-1990. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. pp. 207–214, 239–245. ISBN 978-1-4128-1506-2. ^ a b Sitkowski, Andrzej (2006). UN peacekeeping: myth and reality. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 80–86. ISBN 978-0-275-99214-9. ^ Clairborne, John (7 April 1989). "SWAPO Incursion into Namibia Seen as Major Blunder by Nujoma". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved 18 February 2018. ^ Colletta, Nat; Kostner, Markus; Wiederhofer, Indo (1996). Case Studies of War-To-Peace Transition: The Demobilization and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in Ethiopia, Namibia, and Uganda. Washington DC: World Bank. pp. 127–142. ISBN 978-0821336748. ^ a b c "Namibia Rebel Group Wins Vote, But It Falls Short of Full Control". The New York Times. 15 November 1989. Retrieved 20 June 2014. ^ Namibia gains Independence – South African History Online ^ Dierks, Klaus. "7. The Period after Namibian Independence". Klausdierks.com. Retrieved 21 August 2020. ^ "Treaty between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Namibia with respect to Walvis Bay and the off-shore Islands, 28 February 1994" (PDF). United Nations. ^ "Country report: Spotlight on Namibia". Commonwealth Secretariat. 25 May 2010. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. ^ a b "IRIN country profile Namibia". IRIN. March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2010. ^ "Namibian presidential election won by Swapo's Hage Geingob". BBC News. December 2014. ^ "Namibia's President Hage Geingob wins re-election". BBC News. December 2019.

- Stay safe

A Namibian police car

A Namibian police carNamibia is a peaceful country and is not involved in any wars. Since the end of the Angolan civil war in May 2002, the violence that spilled over into northeastern Namibia is no longer an issue. Namibia is, however, a country with extreme income disparities. A middle manager easily earns twenty times the salary of a cleaner, and a third of the workforce is unemployed. As a tourist you're inevitably seen as stinking rich, and a prime target for thieves.

Namibia has a relatively high crime rate, particularly sexual abuse, general violence after alcohol abuse, and theft. Be careful on or right after pay day, the last day of the month, when there will be more drunk people than anyway usual. Travellers should have no problem visiting the townships, but do not go there on your own, or after dark. In Windhoek you can book township tours where you will be taken to the most interesting places, but that's not the same as going there yourself and see that there are people living there like you and me.

For foreigners, it is not prudent to walk or ride taxis alone after sunset. Pickpockets can be a problem. No local will carry a bag while walking, and for thieves the bag is the token to make out who is a tourist and who isn't. Stuff all possessions into your trousers' pockets. If you rent a car, insist that the owner (rental company) of the car is clearly visible with stickers or as car paint. In the event of carjacking there is no easier way to relax the attitude of the robbers than pointing out that the car isn't yours. Besides, as pretty much all rented cars have hidden communication devices, no carjacker in his right mind will take one from a rental company.

...Read moreStay safeRead less A Namibian police car

A Namibian police carNamibia is a peaceful country and is not involved in any wars. Since the end of the Angolan civil war in May 2002, the violence that spilled over into northeastern Namibia is no longer an issue. Namibia is, however, a country with extreme income disparities. A middle manager easily earns twenty times the salary of a cleaner, and a third of the workforce is unemployed. As a tourist you're inevitably seen as stinking rich, and a prime target for thieves.

Namibia has a relatively high crime rate, particularly sexual abuse, general violence after alcohol abuse, and theft. Be careful on or right after pay day, the last day of the month, when there will be more drunk people than anyway usual. Travellers should have no problem visiting the townships, but do not go there on your own, or after dark. In Windhoek you can book township tours where you will be taken to the most interesting places, but that's not the same as going there yourself and see that there are people living there like you and me.

For foreigners, it is not prudent to walk or ride taxis alone after sunset. Pickpockets can be a problem. No local will carry a bag while walking, and for thieves the bag is the token to make out who is a tourist and who isn't. Stuff all possessions into your trousers' pockets. If you rent a car, insist that the owner (rental company) of the car is clearly visible with stickers or as car paint. In the event of carjacking there is no easier way to relax the attitude of the robbers than pointing out that the car isn't yours. Besides, as pretty much all rented cars have hidden communication devices, no carjacker in his right mind will take one from a rental company.

Most reported robberies take place just outside of the city centre. The police report that taxi drivers are often involved: they spot vulnerable tourists and coordinate by cell phoning. Take these warnings in context; if you are alert and take some common sense precautions, you should have no problems. Never be specific when asked where you stay; "in town" or "at some B&B" is sufficient for all good-faith conversations and doesn't disclose your intended route.

Namibia has a serious problem with driving under the influence of alcohol. The problem is aggravated because most people consider it no problem. When driving or walking on weekend evenings, be especially alert. The person in a car (the more expensive the better) is more important, and has the right of way. This specifically includes zebra crossings and green pedestrian traffic lights—even expats and fellow tourists will not stop for someone on foot in order not to confuse local drivers.

Prostitution is legal but soliciting is not, that's why there are no brothels. Bars that are frequented by tourists will attract prostitutes at night. It is not a good idea to pick one from the street because those are the ones that have been banned from the bars, for whatever reason.