Acoma Pueblo

Acoma Pueblo ( AK-ə-mə, Western Keres: Áakʼu) is a Native American pueblo approximately 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States.

Four communities make up the village of Acoma Pueblo: Sky City (Old Acoma), Acomita, Anzac, and McCartys. These communities are located near the expansive Albuquerque metropolitan area, which includes several large cities and towns, including neighboring Laguna Pueblo. The Acoma Pueblo tribe is a federally recognized tribal entity, whose historic land of Acoma Pueblo totaled roughly 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha). Today, much of the Acoma community is primarily within the Acoma Indian Reservation. Acoma Pueblo is a National Historic Landmark.

According to the 2010 United States Census, 4,989 people identified as Acoma. The Acoma have continuously occupied the area for over 2000 years,...Read more

Acoma Pueblo ( AK-ə-mə, Western Keres: Áakʼu) is a Native American pueblo approximately 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States.

Four communities make up the village of Acoma Pueblo: Sky City (Old Acoma), Acomita, Anzac, and McCartys. These communities are located near the expansive Albuquerque metropolitan area, which includes several large cities and towns, including neighboring Laguna Pueblo. The Acoma Pueblo tribe is a federally recognized tribal entity, whose historic land of Acoma Pueblo totaled roughly 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha). Today, much of the Acoma community is primarily within the Acoma Indian Reservation. Acoma Pueblo is a National Historic Landmark.

According to the 2010 United States Census, 4,989 people identified as Acoma. The Acoma have continuously occupied the area for over 2000 years, making this one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States (along with Taos and Hopi pueblos). Acoma tribal traditions estimate that they have lived in the village for more than two thousand years.

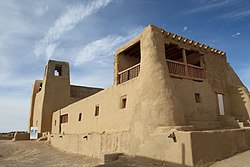

Acoma Pueblo Sky City aerial view

Acoma Pueblo Sky City aerial view A view of the Acoma Pueblo mesa from the northwestOrigins and prehistory

A view of the Acoma Pueblo mesa from the northwestOrigins and prehistory

Pueblo people are believed to have descended from the Ancestral Puebloans, Mogollon, and other ancient peoples. These influences are seen in the architecture, farming style, and artistry of the Acoma. In the 13th century, the Ancestral Puebloans abandoned their canyon homelands due to climate change and social upheaval. For more than two centuries, there were migrations in the area. The Acoma Pueblo emerged by the 13th century.[1] However, the Acoma themselves say the Sky City Pueblo was established in the 11th century, with brick buildings as early as 1144 on the mesa. Evidence for their antiquity is the unique lack of adobe in their construction. This early founding date makes Acoma Pueblo one of the earliest continuously inhabited communities in the United States.[2][3]

The Pueblo is situated on a 365-foot (111 m) mesa, about 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The isolation and location of the Pueblo has sheltered the community for more than 1,200 years as they sought protection from the raids of the neighboring Navajo and Apache peoples.[3]

European contactThe first mention of Acoma was in 1539. Estevanico, a slave, was the first non-Indian to visit Acoma and reported it to Marcos de Niza, who related the information to the viceroy of New Spain after the end of his expedition. Acoma was called the independent Kingdom of Hacus. He called the Acoma people encaconados, which meant that they had turquoise hanging from their ears and noses.[4][5]

Lieutenant[6] Hernando de Alvarado of conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado's expedition described the Pueblo (which they called Acuco) in 1540 as "a very strange place built upon solid rock" and "one of the strongest places we have seen." Upon visiting the Pueblo, the expedition "repented having gone up to the place." Further from Alvarado's report:

These people were robbers, feared by the whole country round about. The village was very strong, because it was up on a rock out of reach, having steep sides in every direction... There was only one entrance by a stairway built by hand... There was a broad stairway of about 200 steps, then a stretch of about 100 narrower steps and at the top they had to go up about three times as high as a man by means of holes in the rock, in which they put the points of their feet, holding on at the same time by their hands. There was a wall of large and small stones at the top, which they could roll down without showing themselves, so that no army could possibly be strong enough to capture the village. On the top they had room to sow and store a large amount of corn, and cisterns to collect snow and water.[7]

It is believed Coronado's expedition were the first Europeans to encounter the Acoma (Estevan was a native Moroccan).[3] Alvarado reported that first the Acoma refused entry even after persuasions, but after Alvarado showed threats of an attack, the Acoma guards welcomed the Spaniards peacefully, noting that they and their horses were tired. The encounter shows that the Acoma had clothing made of deerskin, buffalohide, and woven cotton, as well as turquoise jewelry, domestic turkeys, bread, pine nuts, and maize. The village seemed to contain about 200 men.

Acoma was next visited by the Spanish 40 years later in 1581 by Fray Agustín Rodríguez and Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado, with 12 soldiers, 3 other friars, and 13 others, including Indian servants. The Acoma at this time were reported to be somewhat defensive and fearful. This response may have been due to the knowledge of the Spanish enslavement of other Indians to work in silver mines in the area. However, eventually the Rodríguez and Chamuscado party convinced them to trade goods for food. The Spaniard reports say the pueblo had about 500 houses of either three or four stories high.

In 1582, Acoma was visited again by Antonio de Espejo for three months. The Acoma were reported to be wearing mantas. Espejo also noted irrigation in Acomita, the farming village in the north valley near San Jose River, which was two leagues from the mesa. He saw evidence of intertribal trade with "mountain Querechos". Acoma oral history does not confirm this trade but only tells of common messengers to and from the mesa and Acomita, McCartys Village, and Seama.[8][5][4][9]

Juan de Oñate intended to colonize New Mexico starting from 1595 (he formally held the area by April 1598). The Acoma warrior Zutacapan heard of this plan and warned the mesa and organized a defense. However, a pueblo elder, Chumpo, dissuaded war, partly to prevent deaths and partly based on Zutancalpo's (Zutacapan's son) mentioning of the widespread belief that the Spaniards were immortal. Thus, when Oñate visited on October 27, 1598, Acoma met him peacefully, with no resistance to Oñate's demand of surrender and obedience reported. Oñate demonstrated his military power by firing a gun salute. Zutacapan offered to meet Oñate formally in the religious kiva, which is traditionally used as the place to make sacred oaths and pledges. However, Oñate was scared of death and in suspicious ignorance of Acoma customs refused to enter via ladder from the roof into the dark kiva chambers. Purguapo was another Acoma man out of four chosen for Spaniard negotiations.[5][9]

Soon after Oñate's departure, Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá visited Acoma by himself with a dog and a horse and asked for other supplies. Villagrá refused to get off his horse and left to follow Oñate's party. However, Zutacapan convinced him to return to receive supplies. In questioning by Zutacapan, Villagrá said that 103 armed men were two days away from Acoma. Zutacapan then told Villagrá to leave Acoma.[5][9]

On December 1, 1598, Juan de Zaldívar, Oñate's nephew, reached Acoma with 20–30 men and peacefully traded with them and had to wait some days for their order of ground corn. On December 4, Zaldívar went with 16 armored men to Acoma to find out about the corn. Zutacapan met them and directed them to the homes with the corn. Zaldívar's people then divided into groups to collect the corn. The traditional oral Acoma narrative tells that a group attacked some Acoma women, leading Acoma warriors to retaliate. The Spanish documents do not report an attack on the women and say that the division of the men was a reaction to Zutacapan's plan to kill Zaldívar's party. The Acoma killed 12 of the Spaniards, including Zaldívar. Five men escaped, although one died from jumping over the citadel, leaving four to escape with the remaining camp.[9]

On December 20, 1598, Oñate learned of Zaldívar's death and, after receiving encouraging advice from the friars, planned an attack in revenge, as well to teach a lesson to other pueblos. Acomas requested help from other tribes to defend against the Spanish. Among the leaders were Gicombo, Popempol, Chumpo, Calpo, Buzcoico, Ezmicaio, and Bempol (a recruited Apache war leader). On January 21, 1599, Vicente de Zaldívar (Juan de Zaldívar's brother) reached Acoma with 70 soldiers. The Acoma Massacre started the next day and lasted for three days. On January 23, men were able to climb the southern mesa unnoticed by Acoma guards and breach the pueblo. The Spanish dragged a cannon through the streets, toppling adobe walls and burning most of the village, killing 800 people (decimating 20% of the 4,000 population) and imprisoning approximately 500 others. Almost all of the remaining inhabitants were enslaved or left the town. The pueblo surrendered at noon on January 24. Zaldívar lost only one of his men. The Spanish amputated the right feet of men over 25 years old and forced them into slavery for 20 years. They also took males aged 12–25 and females over 12 away from their parents, putting most of them in slavery for 20 years. The enslaved Acoma were given to government officials and various missions. Two other Indian men visiting Acoma at the time had their right hands cut off and were sent back to their respective Pueblos as a warning of the consequences for resisting the Spanish.[5][10][9] On the north side of the mesa, a row of houses still retains marks from the fire started by a cannon during this Acoma War.[3] (Oñate was later exiled from New Mexico for mismanagement, false reporting, and cruelty by Philip III of Spain.)

Mission San Esteban Rey was built c.1641, photograph by Ansel Adams, c.1941

Mission San Esteban Rey was built c.1641, photograph by Ansel Adams, c.1941 A view from 2009 of the same building, where architectural modifications are apparent

A view from 2009 of the same building, where architectural modifications are apparentSurvivors of the Acoma Massacre rebuilt their community between 1599 and 1620. The town remained uninhabited for several months, out of fear of more attacks, until it began to be rebuilt in December 1599. Oñate forced the Acoma and other local Indians to pay taxes in crops, cotton, and labor. Spanish rule also brought Catholic missionaries into the area. The Spanish renamed the pueblos with the names of saints and started to construct churches in them. They introduced new crops to the Acoma, including peaches, peppers, and wheat. A 1620 royal decree created Spanish civil offices in each pueblo, including Acoma, with an appointed governor to take command. In 1680, the Pueblo Revolt took place, with Acoma participating.[3] The revolt brought refugees from other pueblos. Those who eventually left Acoma moved elsewhere to form Laguna Pueblo.[11]

The Acoma suffered high mortality from smallpox epidemics, as they had no immunity to such Eurasian infectious diseases. They also suffered raiding from the Apache, Comanche, and Ute. On occasion, the Acoma would side with the Spanish to fight against these nomadic tribes. Forced to formally adopt Catholicism, the Acoma proceeded to practice their traditional religion in secrecy, and combined elements of both in a syncretic blend. Intermarriage and interaction became common among the Acoma, other pueblos, and Hispanic villages. These communities would intermingle in a kind of creolization to form the culture of New Mexico.[12]

San Esteban Del Rey MissionBetween 1629 and 1641 Father Juan Ramirez oversaw construction of the San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church. The Acoma were ordered to build the church, moving 20,000 short tons (18,000 t) of adobe, straw, sandstone, and mud to the mesa for the church walls. Ponderosa pine was brought in by community members from Mount Taylor, over 40 miles (64 km) away. The 6,000 square feet (560 m2) church has an altar flanked by 60 feet (18 m)-high wood pillars. These are hand carved in red and white designs, representing Christian and Indigenous beliefs. The Acoma know their ancestors' hands built this structure, and they consider it a cultural treasure.

In 1970, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13] In 2007, the mission church was designated a National Trust Historic Site, the only Native American site in that ranking as identified by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a non-profit organization.[3]

19th and 20th century The pueblo 1933–1942 (Ansel Adams)

The pueblo 1933–1942 (Ansel Adams)During the 19th century, the Acoma people, while trying to uphold traditional life, also adopted aspects of the once-rejected Spanish culture and religion. By the 1880s, railroads brought increased numbers of settlers and ended the pueblos' isolation.

In the 1920s, the All Indian Pueblo Council gathered for the first time in more than 300 years. Responding to congressional interest in appropriating Pueblo lands, the U.S. Congress passed the Pueblo Lands Act in 1924. Despite successes in retaining their land, the Acoma had difficulty in preserving their cultural traditions in the 20th century. Protestant missionaries established schools in the area, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs forced Acoma children into boarding schools. By 1922, most children from the community were in boarding schools, where they were forced to use English and practice Christianity.[12] Several generations became cut off from their culture and language, with harsh effects on their families and societies.

Present day A street in the pueblo, 2012

A street in the pueblo, 2012About 300 two- and three-story adobe buildings stand on the mesa, with exterior ladders used to access the upper levels where residents live. Access to the mesa is by a road blasted into the rock face during the 1950s, navigable by car and bus. Footpaths down the mesa can still be used. Approximately 30[11] or so people live permanently on the mesa, with the population increasing on the weekends, as family members come to visit, and tourists, some 55,000 annually, visit for the day.

Acoma Pueblo has no electricity, running water, or sewage disposal.[11] Reservation lands surround the mesa, totaling 600 square miles (1,600 km2). Tribal members live both on the reservation and outside it.[3] Contemporary Acoma culture remains relatively closed.[14] According to the 2000 United States census, 4,989 people identify themselves as Acoma.[3]

Add new comment