Western Sahara

Context of Western Sahara

Western Sahara (Arabic: الصحراء الغربية aṣ-Ṣaḥrā' al-Gharbiyyah; Berber languages: Taneẓroft Tutrimt; Spanish: Sáhara Occidental) is a disputed territory on the northwest coast and in the Maghreb region of North and West Africa. About 20% of the territory is controlled by the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR); the remaining 80% of the territory is occupied and administered by neighboring Morocco. It has a surface area of 266,000 square kilometres (103,000 sq mi). It is the second most sparsely populated country in the world and the most sparsely populated in Africa, mainly consisting of desert flatlands. The population is estimated at just over 500,000, of which nearly 40% live in Laayoune, the largest city in Western Sahara.

Occupied by Spain until 1975, Western Sah...Read more

Western Sahara (Arabic: الصحراء الغربية aṣ-Ṣaḥrā' al-Gharbiyyah; Berber languages: Taneẓroft Tutrimt; Spanish: Sáhara Occidental) is a disputed territory on the northwest coast and in the Maghreb region of North and West Africa. About 20% of the territory is controlled by the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR); the remaining 80% of the territory is occupied and administered by neighboring Morocco. It has a surface area of 266,000 square kilometres (103,000 sq mi). It is the second most sparsely populated country in the world and the most sparsely populated in Africa, mainly consisting of desert flatlands. The population is estimated at just over 500,000, of which nearly 40% live in Laayoune, the largest city in Western Sahara.

Occupied by Spain until 1975, Western Sahara has been on the United Nations list of non-self-governing territories since 1963 after a Moroccan demand. It is the most populous territory on that list, and by far the largest in area. In 1965, the United Nations General Assembly adopted its first resolution on Western Sahara, asking Spain to decolonize the territory. One year later, a new resolution was passed by the General Assembly requesting that a referendum be held by Spain on self-determination. In 1975, Spain relinquished administrative control of the territory to a joint administration by Morocco, which had formally claimed the territory since 1957 and Mauritania. A war erupted between those countries and a Sahrawi nationalist movement, the Polisario Front, which proclaimed itself the rightful leadership of the SADR with a government in exile in Tindouf, Algeria. Mauritania withdrew its claims in 1979, and Morocco eventually secured de facto control of most of the territory, including all major cities and most natural resources. The United Nations considers the Polisario Front to be the legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people, and maintains that the Sahrawis have a right to self-determination.

Since a United Nations-sponsored ceasefire agreement in 1991, two-thirds of the territory, including most of the Atlantic coastline, has been administered by the Moroccan government, with tacit support from France and the United States. The remainder of the territory is administered by the SADR, backed by Algeria. The only part of the coast outside the Moroccan Western Sahara Wall is the extreme south, including the Ras Nouadhibou peninsula. Internationally, countries such as Russia have taken a generally ambiguous and neutral position on each side's claims and have pressed both parties to agree on a peaceful resolution. Both Morocco and Polisario have sought to boost their claims by accumulating formal recognition, especially from African, Asian, and Latin American states in the developing world. The Polisario Front has won formal recognition for SADR from 46 states, and was extended membership in the African Union. Morocco has won support for its position from several African governments and from most of the Muslim world and Arab League. In both instances, recognitions have, over the past two decades, been extended and withdrawn back and forth, usually depending on relations with Morocco.

Until 2020, no other member state of the United Nations had ever officially recognized Moroccan sovereignty over parts of Western Sahara. In 2020, the United States recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Moroccan normalization of relations with Israel.

In 1984, the African Union's predecessor, the Organization of African Unity, recognized the SADR as one of its full members, with the same status as Morocco, and Morocco protested by suspending its membership to the OAU. Morocco was readmitted in the African Union on 30 January 2017 after promising that the conflicting claims would be resolved peacefully and that it would stop building walls to extend its military control. Meanwhile, the African Union has not issued any formal statement about the border separating the sovereign territories of Morocco and the SADR in Western Sahara. Instead, the African Union works with the United Nations mission to try to maintain the ceasefire and reach a peace agreement between its two members. The African Union provides a peacekeeping contingent to the UN mission which is used to control a buffer zone near the de facto border walls built by Morocco within Western Sahara.

More about Western Sahara

- Currency Moroccan dirham

- Calling code +212

- Population 582000

- Area 266000

- Driving side right

- Early history

The earliest known inhabitants of Western Sahara were the Gaetuli. Depending on the century, Roman-era sources describe the area as inhabited by Gaetulian Autololes or the Gaetulian Daradae tribes. Berber heritage is still evident from regional and place-name toponymy, as well as from tribal names.

Other early inhabitants of Western Sahara may be the Bafour[1] and later the Serer. The Bafour were later replaced or absorbed by Berber-speaking populations, which eventually merged in turn with the migrating Beni Ḥassān Arab tribes.

The arrival of Islam in the 8th century played a major role in the development of the Maghreb region. Trade developed further, and the territory may have been one of the routes for caravans, especially between Marrakesh and Tombouctou in Mali.

...Read moreEarly historyRead lessThe earliest known inhabitants of Western Sahara were the Gaetuli. Depending on the century, Roman-era sources describe the area as inhabited by Gaetulian Autololes or the Gaetulian Daradae tribes. Berber heritage is still evident from regional and place-name toponymy, as well as from tribal names.

Other early inhabitants of Western Sahara may be the Bafour[1] and later the Serer. The Bafour were later replaced or absorbed by Berber-speaking populations, which eventually merged in turn with the migrating Beni Ḥassān Arab tribes.

The arrival of Islam in the 8th century played a major role in the development of the Maghreb region. Trade developed further, and the territory may have been one of the routes for caravans, especially between Marrakesh and Tombouctou in Mali.

In the 11th century, the Maqil Arabs (fewer than 200 individuals) settled in Morocco (mainly in the Draa River valley, between the Moulouya River, Tafilalt and Taourirt).[2] Towards the end of the Almohad Caliphate, the Beni Hassan, a sub-tribe of the Maqil, were called by the local ruler of the Sous to quell a rebellion; they settled in the Sous Ksours and controlled such cities as Taroudant.[2] During Marinid dynasty rule, the Beni Hassan rebelled but were defeated by the Sultan and escaped beyond the Saguia el-Hamra dry river.[2][3] The Beni Hassan then were at constant war with the Lamtuna nomadic Berbers of the Sahara. Over roughly five centuries, through a complex process of acculturation and mixing seen elsewhere in the Maghreb and North Africa, some of the indigenous Berber tribes mixed with the Maqil Arab tribes and formed a culture unique to Morocco and Mauritania.[citation needed]

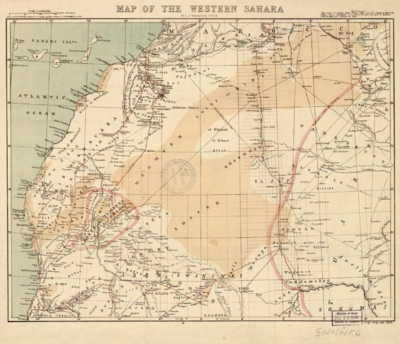

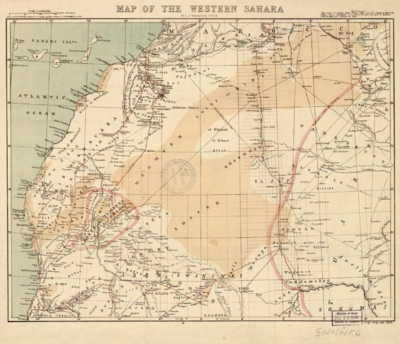

Spanish province Western Sahara 1876

Western Sahara 1876While initial Spanish interest in the Sahara was focused on using it as a port for the slave trade, by the 1700s Spain had transitioned economic activity on the Saharan coast towards commercial fishing.[4] After an agreement among the European colonial powers at the Berlin Conference in 1884 on the division of spheres of influence in Africa, Spain seized control of Western Sahara and established it as a Spanish colony.[5] After 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, this area was administered by Spanish Morocco. As a consequence, Ahmed Belbachir Haskouri, the Chief of Cabinet, General Secretary of the Government of Spanish Morocco, cooperated with the Spanish to select governors in that area. The Saharan lords who were already in prominent positions, such as the members of Maa El Ainain family, provided a recommended list of candidates for new governors. Together with the Spanish High Commissioner, Belbachir selected from this list.[citation needed] During the annual celebration of Muhammad's birthday, these lords paid their respects to the caliph to show loyalty to the Moroccan monarchy.[citation needed]

Spanish and French protectorates in Morocco and Spanish Sahara, 1912

Spanish and French protectorates in Morocco and Spanish Sahara, 1912As time went by, Spanish colonial rule began to unravel with the general wave of decolonization after World War II; former North African and sub-Saharan African possessions and protectorates gained independence from European powers. Spanish decolonization proceeded more slowly, but internal political and social pressures for it in mainland Spain built up towards the end of Francisco Franco's rule. There was a global trend towards complete decolonization. Spain began rapidly to divest itself of most of its remaining colonial possessions. By 1974–75 the government issued promises of a referendum on independence in Western Sahara.

At the same time, Morocco and Mauritania, which had historical and competing claims of sovereignty over the territory, argued that it had been artificially separated from their territories by the European colonial powers. Algeria, which also bordered the territory, viewed their demands with suspicion, as Morocco also claimed the Algerian provinces of Tindouf and Béchar. After arguing for a process of decolonization to be guided by the United Nations, the Algerian government under Houari Boumédiènne in 1975 committed to assisting the Polisario Front, which opposed both Moroccan and Mauritanian claims and demanded full independence of Western Sahara.

The UN attempted to settle these disputes through a visiting mission in late 1975, as well as a verdict from the International Court of Justice (ICJ). It acknowledged that Western Sahara had historical links with Morocco and Mauritania, but not sufficient to prove the sovereignty of either State over the territory at the time of the Spanish colonization. The population of the territory thus possessed the right of self-determination. On 6 November 1975 Morocco initiated the Green March into Western Sahara; 350,000 unarmed Moroccans converged on the city of Tarfaya in southern Morocco and waited for a signal from King Hassan II of Morocco to cross the border in a peaceful march. A few days before, on 31 October, Moroccan troops invaded Western Sahara from the north.[6]

Demands for independence System of the Moroccan Walls in Western Sahara set up in the 1980s

System of the Moroccan Walls in Western Sahara set up in the 1980s Commemoration of the 30th independence day from Spain in the Liberated Territories (2005)

Commemoration of the 30th independence day from Spain in the Liberated Territories (2005)In the waning days of General Franco's rule, and after the Green March, the Spanish government signed a tripartite agreement with Morocco and Mauritania as it moved to transfer the territory on 14 November 1975. The accords were based on a bipartite administration, and Morocco and Mauritania each moved to annex the territories, with Morocco taking control of the northern two-thirds of Western Sahara as its Southern Provinces, and Mauritania taking control of the southern third as Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Spain terminated its presence in Spanish Sahara within three months, repatriating Spanish remains from its cemeteries.[7]

The Moroccan and Mauritanian annexations were resisted by the Polisario Front, which had gained backing from Algeria.[8] It initiated guerrilla warfare and, in 1979, Mauritania withdrew due to pressure from Polisario, including a bombardment of its capital and other economic targets. Morocco extended its control to the rest of the territory. It gradually contained the guerrillas by setting up the extensive sand-berm in the desert (known as the Border Wall or Moroccan Wall) to exclude guerrilla fighters.[9][10] Hostilities ceased in a 1991 cease-fire, overseen by the peacekeeping mission MINURSO, under the terms of a UN Settlement Plan.

Stalling of the referendum and Settlement PlanThe referendum, originally scheduled for 1992, foresaw giving the local population the option between independence or affirming integration with Morocco, but it quickly stalled. In 1997, the Houston Agreement attempted to revive the proposal for a referendum but likewise has hitherto not had success. As of 2010[update], negotiations over terms have not resulted in any substantive action. At the heart of the dispute lies the question of who qualifies to be registered to participate in the referendum, and, since about the year 2000, Morocco considers that since there is no agreement on persons entitled to vote, a referendum is not possible. Meanwhile, Polisario still insisted on a referendum with independence as a clear option, without offering a solution to the problem of who is qualified to be registered to participate in it.

Both sides blame each other for the stalling of the referendum. The Polisario has insisted on only allowing those found on the 1974 Spanish Census lists (see below) to vote, while Morocco has insisted that the census was flawed by evasion and sought the inclusion of members of Sahrawi tribes that escaped from Spanish invasion to the north of Morocco by the 19th century.

Efforts by the UN special envoys to find a common ground for both parties did not succeed. By 1999 the UN had identified about 85,000 voters, with nearly half of them in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara or Southern Morocco, and the others scattered between the Tindouf refugee camps, Mauritania and other places of exile. Polisario accepted this voter list, as it had done with the previous list presented by the UN (both of them originally based on the Spanish census of 1974), but Morocco refused and, as rejected voter candidates began a mass-appeals procedure, insisted that each application be scrutinized individually. This again brought the process to a halt.

According to a NATO delegation, MINURSO election observers stated in 1999, as the deadlock continued, that "if the number of voters does not rise significantly the odds were slightly on the SADR side".[11] By 2001, the process had effectively stalemated and the UN Secretary-General asked the parties for the first time to explore other, third-way solutions. Indeed, shortly after the Houston Agreement (1997), Morocco officially declared that it was "no longer necessary" to include an option of independence on the ballot, offering instead autonomy. Erik Jensen, who played an administrative role in MINURSO, wrote that neither side would agree to a voter registration in which they were destined to lose (see Western Sahara: Anatomy of a Stalemate).

Baker PlanAs personal envoy of the Secretary-General, James Baker visited all sides and produced the document known as the "Baker Plan".[12] This was discussed by the United Nations Security Council in 2000, and envisioned an autonomous Western Sahara Authority (WSA), which would be followed after five years by the referendum. Every person present in the territory would be allowed to vote, regardless of birthplace and with no regard to the Spanish census. It was rejected by both sides, although it was initially derived from a Moroccan proposal. According to Baker's draft, tens of thousands of post-annexation immigrants from Morocco proper (viewed by Polisario as settlers but by Morocco as legitimate inhabitants of the area) would be granted the vote in the Sahrawi independence referendum, and the ballot would be split three ways by the inclusion of an unspecified "autonomy", further undermining the independence camp. Morocco was also allowed to keep its army in the area and retain control over all security issues during both the autonomy years and the election. In 2002, the Moroccan king stated that the referendum idea was "out of date" since it "cannot be implemented";[13] Polisario retorted that that was only because of the King's refusal to allow it to take place.

In 2003, a new version of the plan was made official, with some additions spelling out the powers of the WSA, making it less reliant on Moroccan devolution. It also provided further detail on the referendum process in order to make it harder to stall or subvert. This second draft, commonly known as Baker II, was accepted by the Polisario as a "basis of negotiations" to the surprise of many.[14] This appeared to abandon Polisario's previous position of only negotiating based on the standards of voter identification from 1991 (i.e. the Spanish census). After that, the draft quickly garnered widespread international support, culminating in the UN Security Council's unanimous endorsement of the plan in the summer of 2003.

End of the 2000sParts of this article (those related to the Manhasset negotiations (not in article)) need to be updated. (September 2013)Baker resigned his post at the United Nations in 2004; his term did not see the crisis resolved.[15] His resignation followed several months of failed attempts to get Morocco to enter into formal negotiations on the plan, but he was met with rejection.

King Hassan II of Morocco initially supported the referendum idea in principle in 1982, and signed contracts with Polisario and the UN in 1991 and 1997. No major powers have expressed interest in forcing the issue, however, and Morocco has shown little interest in a real referendum. Hassan II's son and successor, Mohammed VI, has opposed any referendum on independence, and has said Morocco will never agree to one: "We shall not give up one inch of our beloved Sahara, not a grain of its sand."[16] In 2006, he created an appointed advisory body Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), which proposes a self-governing Western Sahara as an autonomous community within Morocco.

The UN has put forth no replacement strategy after the breakdown of Baker II, and renewed fighting has been raised as a possibility. In 2005, former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan reported increased military activity on both sides of the front and breaches of several cease-fire provisions against strengthening military fortifications.

Morocco has repeatedly tried to engage Algeria in bilateral negotiations, based on its view of Polisario as the cat's paw of the Algerian military. It has received vocal support from France and occasionally (and currently) from the United States. These negotiations would define the exact limits of a Western Sahara autonomy under Moroccan rule but only after Morocco's "inalienable right" to the territory was recognized as a precondition to the talks. The Algerian government has consistently refused, claiming it has neither the will nor the right to negotiate on the behalf of the Polisario Front.

Demonstrations and riots by supporters of independence or a referendum broke out in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara in May 2005 and in parts of southern Morocco (notably the town of Assa). They were met by police. Several international human rights organizations expressed concern at what they termed abuse by Moroccan security forces, and a number of Sahrawi activists have been jailed. Pro-independence Sahrawi sources, including the Polisario, have given these demonstrations the name "Independence Intifada", while most sources have tended to see the events as being of limited importance. International press and other media coverage have been sparse, and reporting is complicated by the Moroccan government's policy of strictly controlling independent media coverage within the territory.

A demonstration in Madrid for the independence of Western Sahara

A demonstration in Madrid for the independence of Western SaharaDemonstrations and protests still occur, even after Morocco declared in February 2006 that it was contemplating a plan for devolving a limited variant of autonomy to the territory but still explicitly refused any referendum on independence. As of January 2007, the plan had not been made public, though the Moroccan government claimed that it was more or less complete.[17]

Polisario has intermittently threatened to resume fighting, referring to the Moroccan refusal of a referendum as a breach of the cease-fire terms, but most observers seem to consider armed conflict unlikely without the green light from Algeria, which houses the Sahrawis' refugee camps and has been the main military sponsor of the movement.

In April 2007, the government of Morocco suggested that a self-governing entity, through the CORCAS, should govern the territory with some degree of autonomy for Western Sahara. The project was presented to the UN Security Council in mid-April 2007. The stalemating of the Moroccan proposal options has led the UN in the recent "Report of the UN Secretary-General" to ask the parties to enter into direct and unconditional negotiations to reach a mutually accepted political solution.[18]

The 2010s A MINURSO car (left), and a post of the Polisario Front (right) in 2017 in southern Western Sahara

A MINURSO car (left), and a post of the Polisario Front (right) in 2017 in southern Western SaharaIn October 2010 Gadaym Izik camp was set up near Laayoune as a protest by displaced Sahrawi people about their living conditions. It was home to more than 12,000 people. In November 2010 Moroccan security forces entered Gadaym Izik camp in the early hours of the morning, using helicopters and water cannon to force people to leave. The Polisario Front said Moroccan security forces had killed a 26-year-old protester at the camp, a claim denied by Morocco. Protesters in Laayoune threw stones at police and set fire to tires and vehicles. Several buildings, including a TV station, were also set on fire. Moroccan officials said five security personnel had been killed in the unrest.[19]

On 15 November 2010, the Moroccan government accused the Algerian secret services of orchestrating and financing the Gadaym Izik camp with the intent to destabilize the region. The Spanish press was accused of mounting a campaign of disinformation to support the Sahrawi initiative, and all foreign reporters were either prevented from traveling or else expelled from the area.[20] The protest coincided with a fresh round of negotiations at the UN.[21]

In 2016, the European Union (EU) declared that "Western Sahara is not part of Moroccan territory."[22] In March 2016, Morocco "expelled more than 70 U.N. civilian staffers with MINURSO" due to strained relations after Ban Ki-moon called Morocco's annexation of Western Sahara an "occupation".[23]

The 2020sIn November 2020, the ceasefire between the Polisario Front and Morocco broke down, leading to armed clashes between both sides.

On 10 December 2020, the United States announced that it would recognize full Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco establishing relations with Israel.[24][25][26]

In February 2021, Morocco proposed to Spain the creation of an autonomy for Western Sahara under the sovereignty of the King of Morocco.[27]

In March 2022, the Spanish government abandoned its traditional position of neutrality in the conflict, siding with Rabat and recognising the autonomy proposal "as the most serious, realistic and credible basis for the resolution of the dispute".[28] This sudden turnaround was generally rejected by both the Opposition, the parties that make up the government coalition, the Polisario Front, as well as members of the governing party, who support a solution "that respects the democratic will of the Saharawi people".[29]

^ Handloff, Robert. "The West Sudanic Empires". Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2009. ^ a b c History of Ibn Khaldun Volume 6, pp80-90 by ibn Khaldun ^ Rawd al-Qirtas, Ibn Abi Zar ^ Besenyo, Janos. Western Sahara. Publikon, 2009, P. 49. ^ "ICE Conflict Case ZSahara". .american.edu. 17 March 1997. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ János, Besenyő (2009). Western Sahara (PDF). Pécs: Publikon Publishers. ISBN 978-963-88332-0-4. ^ Tomás Bárbulo, "La historia prohibida del Sáhara Español," Destino, Imago mundi, Volume 21, 2002, Page 292 ^ "Algeria Claims Spanish Sahara Is Being Invaded". The Monroe News-Star. 1 January 1976. Retrieved 19 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com. ^ McNeish, Hannah (5 June 2015). "Western Sahara's Struggle for Freedom Cut Off By a Wall". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 October 2016. ^ "Is One of Africa's Oldest Conflicts Finally Nearing Its End?". Newyorker.com. 29 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018. For the past forty years, tens of thousands of Moroccan soldiers have manned a wall of sand that curls for one and a half thousand miles through the howling Sahara. The vast plain around it is empty and flat, interrupted only by occasional horseshoe dunes that traverse it. But the Berm, as the wall is known, is no natural phenomenon. It was built by the Kingdom of Morocco, in the nineteen-eighties, and it's the longest defensive fortification in use today—and the second-longest ever, after China's Great Wall ^ iBi Center. "NATO PA – Archives". Nato-pa.int. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ United Nations Security Council Document S/2000/461 22 May 2000. ^ "CountryWatch – Interesting Facts of the World". Countrywatch.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ Shelley, Toby. Behind the Baker Plan for Western Sahara Archived 10 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Middle East Report Online, 1 August 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2006. ^ "Western Sahara: Baker Resigns As UN Mediator After Seven Years". 14 June 2004. Retrieved 4 October 2014. ^ "Times News – Bold, Authoritative, and True". Times News. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. ^ "afrol News – No plans for a referendum in Western Sahara". Afrol.com. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ Report of the Secretary-General on the situation concerning Western Sahara (13 April 2007)(ped). UN Security Council[dead link] ^ "Deadly Clashes as Morocco Breaks Up Western Sahara Camp". BBC News. 11 September 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010. ^ "New expulsions of Spanish citizens from Western Sahara". El País. 14 November 2010. ^ Black, Ian (12 November 2010). "Deadly Clashes Stall Western Sahara-Morocco Peace Talks". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2010. ^ Dudley, Dominic (14 September 2016). "Morocco Suffers Legal Setback As EU Official Declares Western Sahara 'Not Part of Morocco'". Forbes. Retrieved 17 October 2016. ^ Lederer, Edith M. (30 August 2016). "UN Document Says Morocco Violated Western Sahara Cease-Fire". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 October 2016.[permanent dead link] ^ Cite error: The named reference Israel1 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ "Morocco latest country to normalise ties with Israel in US-brokered deal". bbc.com. 10 December 2020. ^ Trump, Donald J. [@realdonaldtrump] (10 December 2020). "Morocco recognized the United States in 1777. It is thus fitting we recognize their sovereignty over the Western Sahara" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 December 2020 – via Twitter. ^ "Marruecos intenta que España cambie su posición sobre el Sáhara" [Morocco tries to get Spain to change its position on the Sahara]. El País (in Spanish). 6 February 2021. ^ "España toma partido por Marruecos en el conflicto del Sáhara" [Spain sides with Morocco in the Sahara conflict]. El País (in Spanish). 18 March 2022. ^ "La oposición, Unidas Podemos y socios del Gobierno rechazan la postura de Sánchez con el plan marroquí para el Sáhara" [The Opposition, Unidas Podemos and government partners reject Sánchez's stance on Morocco's Sahara plan]. Heraldo de Aragón (in Spanish). 18 March 2022.

- Stay safe

Hot, dry, dust-and-sand-laden sirocco wind can occur during winter and spring; widespread harmattan haze exists 60% of time, often severely restricting visibility. There are low-level uprisings and political violence which is altogether rare, but can escalate. Occupying powers are likely to evict foreigners in such case.

The N1—and even more so the roads into the heart of the territory—are very remote roads, with facilities and settlements being easily 150–200 km (93–124 mi) away from each other. Take enough fuel (always refuel before going on the next leg, you never know what is going to happen) and enough water (several liters per person). Mobile network connection exists along N1.

Landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO)There was war in Western Sahara for over 15 years in the 1970s and 1980s, and as a result, the landmine and UXO situation to this day remains quite unclear, despite efforts of the Moroccan Government to improve the situation. There are landmines not only in the remote parts of the country close to berm, but all the way down main coastal road (N1) to the Mauritanian border. Google Earth clearly shows the efforts to clear minefields all along N1, which continue to this day—despite Moroccan officers tending to tell tourists that this part of the country is safe. Around the settlements (Boujdour, Ad-Dakhla, Golfe de Cintra) the situation seems to be slightly worse, possibly due their strategic significance in the war. The warning signs are sometimes so rusty that they can't be recognised anymore, but usually the combination of two small metal signs is a strong indicator.

...Read moreStay safeRead lessHot, dry, dust-and-sand-laden sirocco wind can occur during winter and spring; widespread harmattan haze exists 60% of time, often severely restricting visibility. There are low-level uprisings and political violence which is altogether rare, but can escalate. Occupying powers are likely to evict foreigners in such case.

The N1—and even more so the roads into the heart of the territory—are very remote roads, with facilities and settlements being easily 150–200 km (93–124 mi) away from each other. Take enough fuel (always refuel before going on the next leg, you never know what is going to happen) and enough water (several liters per person). Mobile network connection exists along N1.

Landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO)There was war in Western Sahara for over 15 years in the 1970s and 1980s, and as a result, the landmine and UXO situation to this day remains quite unclear, despite efforts of the Moroccan Government to improve the situation. There are landmines not only in the remote parts of the country close to berm, but all the way down main coastal road (N1) to the Mauritanian border. Google Earth clearly shows the efforts to clear minefields all along N1, which continue to this day—despite Moroccan officers tending to tell tourists that this part of the country is safe. Around the settlements (Boujdour, Ad-Dakhla, Golfe de Cintra) the situation seems to be slightly worse, possibly due their strategic significance in the war. The warning signs are sometimes so rusty that they can't be recognised anymore, but usually the combination of two small metal signs is a strong indicator.

Withered Landmine Warning Sign at N1 south of Ad-Dakhla.

Withered Landmine Warning Sign at N1 south of Ad-Dakhla.Keep eyes open to lines of stones, cairns, staples of old tyres and similar man-made marking—they are usually meaningful! Generally, any place off the tarmac-road of N1 and off-branching tarmac roads must be considered unsafe. Car-wrecks are strong indicators—do not explore these! Strategically significant points (the various small passes, narrow valleys, elevated points, etc.) are more dangerous, but this does not mean that other places are safe. Any man-made fortifications (straight sand-walls, round sand-wall [for artillery] and any other military looking movements of ground) pose particular danger (esp. south of Ad-Dakhla, but also south of Boujdour). It might be that these were mined when being abandoned to prevent them from falling into the other party's hand, or it might be that the surroundings were mined from the beginning to protect against guerrilla attacks, but anyway the mine-cleaning patterns strongly indicate that such places were and possibly continue to be particularly dangerous. Few to no mine-clearing efforts can be observed off the N1 - that possibly means that (e.g. for lack of touristic significance) these areas continue to be mined and efforts were focussed at the immediate surrounding of N1.

The patterns of cleaning mine-fields indicate that in not all cases does the Moroccan Government seem to be aware of the location of minefields, which requires more or less random search pattern. Moreover, on Google Earth it can be seen that where minefields have previously been cleared, new clearing activities have resumed later. This again indicates that even traces of cleared minefields do not guarantee safety. This includes the surroundings of the lagoon of Ad-Dakhla, including the lands north of it.