South Africa

Context of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa, is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by 2,798 kilometres (1,739 mi) of coastline that stretches along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countries of Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe; and to the east and northeast by Mozambique and Eswatini. It also completely enclaves the country Lesotho. It is the southernmost country on the mainland of the Old World, and the second-most populous country located entirely south of the equator, after Tanzania. South Africa is a biodiversity hotspot, with unique biomes, plant and animal life. With over 60 million people, the country is the world's 24th-most populous nation and covers an area of 1,221,037 square kilometres (471,445 square miles). Pretoria is the administrative capital, while Cape Town, as the seat of Parliament, is the legislative capital. Bloemfontein has traditionally be...Read more

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa, is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by 2,798 kilometres (1,739 mi) of coastline that stretches along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countries of Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe; and to the east and northeast by Mozambique and Eswatini. It also completely enclaves the country Lesotho. It is the southernmost country on the mainland of the Old World, and the second-most populous country located entirely south of the equator, after Tanzania. South Africa is a biodiversity hotspot, with unique biomes, plant and animal life. With over 60 million people, the country is the world's 24th-most populous nation and covers an area of 1,221,037 square kilometres (471,445 square miles). Pretoria is the administrative capital, while Cape Town, as the seat of Parliament, is the legislative capital. Bloemfontein has traditionally been regarded as the judicial capital. The largest city, and site of highest court is Johannesburg.

About 80% of the population are Black South Africans. The remaining population consists of Africa's largest communities of European (White South Africans), Asian (Indian South Africans and Chinese South Africans), and multiracial (Coloured South Africans) ancestry. South Africa is a multiethnic society encompassing a wide variety of cultures, languages, and religions. Its pluralistic makeup is reflected in the constitution's recognition of 11 official languages, the fourth-highest number in the world. According to the 2011 census, the two most spoken first languages are Zulu (22.7%) and Xhosa (16.0%). The two next ones are of European origin: Afrikaans (13.5%) developed from Dutch and serves as the first language of most Coloured and White South Africans; English (9.6%) reflects the legacy of British colonialism and is commonly used in public and commercial life.

The country is one of the few in Africa never to have had a coup d'état, and regular elections have been held for almost a century. However, the vast majority of Black South Africans were not enfranchised until 1994. During the 20th century, the black majority sought to claim more rights from the dominant white minority, which played a large role in the country's recent history and politics. The National Party imposed apartheid in 1948, institutionalising previous racial segregation. After a long and sometimes violent struggle by the African National Congress and other anti-apartheid activists both inside and outside the country, the repeal of discriminatory laws began in the mid-1980s. Since 1994, all ethnic and linguistic groups have held political representation in the country's liberal democracy, which comprises a parliamentary republic and nine provinces. South Africa is often referred to as the "rainbow nation" to describe the country's multicultural diversity, especially in the wake of apartheid.

South Africa is a middle power in international affairs; it maintains significant regional influence and is a member of both the Commonwealth of Nations and the G20. It is a developing country, ranking 109th on the Human Development Index, the 7th highest on the continent. It has been classified by the World Bank as a newly industrialised country and has the second-largest economy and the most industrialized, technologically advanced economy in Africa overall as well as the 39th-largest economy in the world. South Africa has the most UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa. Since the end of apartheid, government accountability and quality of life have substantially improved. However, crime, poverty and inequality remain widespread, with about 40% of the total population being unemployed as of 2021, while some 60% of the population lived under the poverty line and a quarter under $2.15 a day.

More about South Africa

- Currency South African rand

- Calling code +27

- Internet domain .za

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 7.24

- Population 62027503

- Area 1221037

- Driving side left

- Prehistoric archaeology

Front of Maropeng at the Cradle of Humankind

Front of Maropeng at the Cradle of HumankindSouth Africa contains some of the...Read more

Prehistoric archaeologyRead less Front of Maropeng at the Cradle of Humankind

Front of Maropeng at the Cradle of HumankindSouth Africa contains some of the oldest archaeological and human-fossil sites in the world.[1][2][3] Archaeologists have recovered extensive fossil remains from a series of caves in Gauteng Province. The area, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has been branded "the Cradle of Humankind". The sites include Sterkfontein, one of the richest sites for hominin fossils in the world, as well as Swartkrans, Gondolin Cave, Kromdraai, Cooper's Cave and Malapa. Raymond Dart identified the first hominin fossil discovered in Africa, the Taung Child (found near Taung) in 1924. Other hominin remains have come from the sites of Makapansgat in Limpopo Province; Cornelia and Florisbad in Free State Province; Border Cave in KwaZulu-Natal Province; Klasies River Caves in Eastern Cape Province; and Pinnacle Point, Elandsfontein and Die Kelders Cave in Western Cape Province.

These finds suggest that various hominid species existed in South Africa from about three million years ago, starting with Australopithecus africanus,[4] followed by Australopithecus sediba, Homo ergaster, Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis, Homo helmei, Homo naledi and modern humans (Homo sapiens). Modern humans have inhabited Southern Africa for at least 170,000 years. Various researchers have located pebble tools within the Vaal River valley.[5][6]

Bantu expansion Mapungubwe Hill, the site of the former capital of the Kingdom of Mapungubwe

Mapungubwe Hill, the site of the former capital of the Kingdom of MapungubweSettlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were present south of the Limpopo River (now the northern border with Botswana and Zimbabwe) by the 4th or 5th century CE. They displaced, conquered, and absorbed the original Khoisan, Khoikhoi and San peoples. The Bantu slowly moved south. The earliest ironworks in modern-day KwaZulu-Natal Province are believed to date from around 1050. The southernmost group was the Xhosa people, whose language incorporates certain linguistic traits from the earlier Khoisan people. The Xhosa reached the Great Fish River, in today's Eastern Cape Province. As they migrated, these larger Iron Age populations displaced or assimilated earlier peoples. In Mpumalanga Province, several stone circles have been found along with a stone arrangement that has been named Adam's Calendar, and the ruins are thought to be created by the Bakone, a Northern Sotho people.[7][8]

Portuguese exploration Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias planting the cross at Cape Point after being the first to successfully round the Cape of Good Hope.

Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias planting the cross at Cape Point after being the first to successfully round the Cape of Good Hope.In 1487, the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias led the first European voyage to land in southern Africa.[9] On 4 December, he landed at Walfisch Bay (now known as Walvis Bay in present-day Namibia). This was south of the furthest point reached in 1485 by his predecessor, the Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão (Cape Cross, north of the bay). Dias continued down the western coast of southern Africa. After 8 January 1488, prevented by storms from proceeding along the coast, he sailed out of sight of land and passed the southernmost point of Africa without seeing it. He reached as far up the eastern coast of Africa as, what he called, Rio do Infante, probably the present-day Groot River, in May 1488. On his return he saw the cape, which he named Cabo das Tormentas ('Cape of Storms'). King John II renamed the point Cabo da Boa Esperança, or Cape of Good Hope, as it led to the riches of the East Indies.[10] Dias' feat of navigation was immortalised in Luís de Camões' 1572 epic poem Os Lusíadas.

Dutch colonisation Charles Davidson Bell's 19th-century painting of Jan van Riebeeck, who founded the first European settlement in South Africa, arrives in Table Bay in 1652

Charles Davidson Bell's 19th-century painting of Jan van Riebeeck, who founded the first European settlement in South Africa, arrives in Table Bay in 1652By the early 17th century, Portugal's maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Portugal from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade.[11] Representatives of the British East India Company sporadically called at the cape in search of provisions as early as 1601 but later came to favour Ascension Island and Saint Helena as alternative ports of refuge.[12] Dutch interest was aroused after 1647, when two employees of the Dutch East India Company were shipwrecked at the cape for several months. The sailors were able to survive by obtaining fresh water and meat from the natives.[12] They also sowed vegetables in the fertile soil.[13] Upon their return to Holland, they reported favourably on the cape's potential as a "warehouse and garden" for provisions to stock passing ships for long voyages.[12]

In 1652, a century and a half after the discovery of the cape sea route, Jan van Riebeeck established a victualling station at the Cape of Good Hope, at what would become Cape Town, on behalf of the Dutch East India Company.[14][15] In time, the cape became home to a large population of vrijlieden, also known as vrijburgers (lit. 'free citizens'), former company employees who stayed in Dutch territories overseas after serving their contracts.[15] Dutch traders also brought thousands of enslaved people to the fledgling colony from Indonesia, Madagascar, and parts of eastern Africa.[16] Some of the earliest mixed race communities in the country were formed between vrijburgers, enslaved people, and indigenous peoples.[17] This led to the development of a new ethnic group, the Cape Coloureds, most of whom adopted the Dutch language and Christian faith.[17]

The eastward expansion of Dutch colonists ushered in a series of wars with the southwesterly migrating Xhosa tribe, known as the Xhosa Wars, as both sides competed for the pastureland near the Great Fish River, which the colonists desired for grazing cattle.[18] Vrijburgers who became independent farmers on the frontier were known as Boers, with some adopting semi-nomadic lifestyles being denoted as trekboers.[18] The Boers formed loose militias, which they termed commandos, and forged alliances with Khoisan peoples to repel Xhosa raids.[18] Both sides launched bloody but inconclusive offensives, and sporadic violence, often accompanied by livestock theft, remained common for several decades.[18]

British colonisation and the Great TrekGreat Britain occupied Cape Town between 1795 and 1803 to prevent it from falling under the control of the French First Republic, which had invaded the Low Countries.[18] After briefly returning to Dutch rule under the Batavian Republic in 1803, the cape was occupied again by the British in 1806.[19] Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, it was formally ceded to Great Britain and became an integral part of the British Empire.[20] British emigration to South Africa began around 1818, subsequently culminating in the arrival of the 1820 Settlers.[20] The new colonists were induced to settle for a variety of reasons, namely to increase the size of the European workforce and to bolster frontier regions against Xhosa incursions.[20]

Depiction of a Zulu attack on a Boer camp in February 1838

Depiction of a Zulu attack on a Boer camp in February 1838In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka.[21] Shaka's warfare indirectly led to the Mfecane ('crushing'), in which one to two million people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s.[22][23] An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the highveld under their king Mzilikazi.

During the early 19th century, many Dutch settlers departed from the Cape Colony, where they had been subjected to British control, in a series of migrant groups who came to be known as Voortrekkers, meaning "pathfinders" or "pioneers". They migrated to the future Natal, Free State, and Transvaal regions. The Boers founded the Boer republics: the South African Republic, the Natalia Republic, and the Orange Free State.

The discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1884 in the interior started the Mineral Revolution and increased economic growth and immigration. This intensified British efforts to gain control over the indigenous peoples. The struggle to control these important economic resources was a factor in relations between Europeans and the indigenous population and also between the Boers and the British.[24]

1876 map of South Africa

1876 map of South AfricaOn 16 May 1876, President Thomas François Burgers of the South African Republic declared war against the Pedi people. King Sekhukhune managed to defeat the army on 1 August 1876. Another attack by the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps was also repulsed. On 16 February 1877, the two parties signed a peace treaty at Botshabelo.[25] The Boers' inability to subdue the Pedi led to the departure of Burgers in favour of Paul Kruger and the British annexation of the South African Republic. In 1878 and 1879 three British attacks were successfully repelled until Garnet Wolseley defeated Sekhukhune in November 1879 with an army of 2,000 British soldiers, Boers and 10,000 Swazis.

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British and the Zulu Kingdom. Following Lord Carnarvon's successful introduction of federation in Canada, it was thought that similar political effort, coupled with military campaigns, might succeed with the African kingdoms, tribal areas and Boer republics in South Africa. In 1874, Henry Bartle Frere was sent to South Africa as the British High Commissioner to bring such plans into being. Among the obstacles were the presence of the independent states of the Boers, and the Zululand army. The Zulu nation defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana. Eventually Zululand lost the war, resulting in the termination of the Zulu nation's independence.

Boer Wars The Battle of Majuba Hill was the last decisive battle during the First Boer War, and saw the British defeated by the Boers after 2 hours of fighting.

The Battle of Majuba Hill was the last decisive battle during the First Boer War, and saw the British defeated by the Boers after 2 hours of fighting. Boer women and children in a British concentration camp during the Second Boer War.

Boer women and children in a British concentration camp during the Second Boer War.The Boer republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using guerrilla warfare tactics, which were well-suited to local conditions. The British returned with greater numbers, more experience, and new strategy in the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and, although they suffered heavy casualties through attrition, they were ultimately successful. Over 27,000 Boer women and children died in the British concentration camps.[26]

South Africa's urban population grew rapidly from the end of the 19th century onward. After the devastation of the wars, Dutch-descendant Boer farmers fled into cities from the devastated Transvaal and Orange Free State territories to become the class of the white urban poor.[27]

IndependenceAnti-British policies among white South Africans focused on independence. During the Dutch and British colonial years, racial segregation was mostly informal, though some legislation was enacted to control the settlement and movement of indigenous people, including the Native Location Act of 1879 and the system of pass laws.[28][29][30][31][32]

Eight years after the end of the Second Boer War and after four years of negotiation, the South Africa Act 1909 granted nominal independence while creating the Union of South Africa on 31 May 1910. The union was a dominion that included the former territories of the Cape, Transvaal and Natal colonies, as well as the Orange Free State republic.[33] The Natives' Land Act of 1913 severely restricted the ownership of land by blacks; at that stage they controlled only 7% of the country. The amount of land reserved for indigenous peoples was later marginally increased.[34]

In 1931, the union became fully sovereign from the United Kingdom with the passage of the Statute of Westminster, which abolished the last powers of the Parliament of the United Kingdom to legislate on the country. Only three other African countries—Liberia, Ethiopia, and Egypt—had been independent prior to that point. In 1934, the South African Party and National Party merged to form the United Party, seeking reconciliation between Afrikaners and English-speaking whites. In 1939, the party split over the entry of the union into World War II as an ally of the United Kingdom, a move which the National Party followers strongly opposed.

Beginning of apartheid "For use by white persons" – apartheid sign in English and Afrikaans

"For use by white persons" – apartheid sign in English and AfrikaansIn 1948, the National Party was elected to power. It strengthened the racial segregation begun under Dutch and British colonial rule. Taking Canada's Indian Act as a framework,[35] the nationalist government classified all peoples into three races (Whites, Blacks, Indians and Coloured people (people of mixed race)) and developed rights and limitations for each. The white minority (less than 20%)[36] controlled the vastly larger black majority. The legally institutionalised segregation became known as apartheid. While whites enjoyed the highest standard of living in all of Africa, comparable to First World Western nations, the black majority remained disadvantaged by almost every standard, including income, education, housing, and life expectancy.[37] The Freedom Charter, adopted in 1955 by the Congress Alliance, demanded a non-racial society and an end to discrimination.

RepublicIt has been suggested that portions of this article be split out into another article titled Republic of South Africa (1961 - 1994). (Discuss) (December 2022)On 31 May 1961, the country became a republic following a referendum (only open to white voters) which narrowly passed;[38] the British-dominated Natal province largely voted against the proposal. Elizabeth II lost the title Queen of South Africa, and the last Governor-General, Charles Robberts Swart, became state president. As a concession to the Westminster system, the appointment of the president remained an appointment by parliament and was virtually powerless until P. W. Botha's Constitution Act of 1983, which eliminated the office of prime minister and instated a unique "strong presidency" responsible to parliament. Pressured by other Commonwealth of Nations countries, South Africa withdrew from the organisation in 1961 and rejoined it in 1994.

Despite opposition to apartheid both within and outside the country, the government legislated for a continuation of apartheid. The security forces cracked down on internal dissent, and violence became widespread, with anti-apartheid organisations such as the African National Congress (ANC), the Azanian People's Organisation, and the Pan-Africanist Congress carrying out guerrilla warfare[39] and urban sabotage.[40] The three rival resistance movements also engaged in occasional inter-factional clashes as they jockeyed for domestic influence.[41] Apartheid became increasingly controversial, and several countries began to boycott business with the South African government because of its racial policies. These measures were later extended to international sanctions and the divestment of holdings by foreign investors.[42][43]

End of apartheid F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela shake hands in January 1992

F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela shake hands in January 1992The Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith, signed by Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Harry Schwarz in 1974, enshrined the principles of peaceful transition of power and equality for all, the first of such agreements by black and white political leaders in South Africa. Ultimately, F.W. de Klerk opened bilateral discussions with Nelson Mandela in 1993 for a transition of policies and government.

In 1990, the National Party government took the first step towards dismantling discrimination when it lifted the ban on the ANC and other political organisations. It released Nelson Mandela from prison after 27 years of serving a sentence for sabotage. A negotiation process followed. With approval from the white electorate in a 1992 referendum, the government continued negotiations to end apartheid. South Africa held its first universal elections in 1994, which the ANC won by an overwhelming majority. It has been in power ever since. The country rejoined the Commonwealth of Nations and became a member of the Southern African Development Community.

In post-apartheid South Africa, unemployment remained high. While many blacks have risen to middle or upper classes, the overall unemployment rate of black people worsened between 1994 and 2003 by official metrics but declined significantly using expanded definitions.[44] Poverty among whites, which was previously rare, increased.[45] The government struggled to achieve the monetary and fiscal discipline to ensure both redistribution of wealth and economic growth. The United Nations Human Development Index rose steadily until the mid-1990s[46] then fell from 1995 to 2005 before recovering its 1995 peak in 2013.[47] The fall is in large part attributable to the South African HIV/AIDS pandemic which saw South African life expectancy fall from a high point of 62 years in 1992 to a low of 53 in 2005,[48] and the failure of the government to take steps to address the pandemic in its early years.[49]

Supporters watching the 2010 FIFA World Cup with vuvuzelas in the township of Soweto, a suburb of Johannesburg

Supporters watching the 2010 FIFA World Cup with vuvuzelas in the township of Soweto, a suburb of Johannesburg March in Johannesburg against xenophobia in South Africa, 23 April 2015

March in Johannesburg against xenophobia in South Africa, 23 April 2015In May 2008, riots left over 60 people dead.[50] The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions estimated that over 100,000 people were driven from their homes.[51] The targets were mainly legal and illegal migrants, and refugees seeking asylum, but a third of the victims were South African citizens.[50] In a 2006 survey, the South African Migration Project concluded that South Africans are more opposed to immigration than any other national group.[52] The UN High Commissioner for Refugees in 2008 reported over 200,000 refugees applied for asylum in South Africa, almost four times as many as the year before.[53] These people were mainly from Zimbabwe, though many also come from Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.[53] Competition over jobs, business opportunities, public services and housing has led to tension between refugees and host communities.[53] While xenophobia in South Africa is still a problem, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 2011 reported that recent violence had not been as widespread as initially feared.[53] Nevertheless, as South Africa continues to grapple with racial issues, one of the proposed solutions has been to pass legislation, such as the pending Hate Crimes and Hate Speech Bill, to uphold South Africa's ban on racism and commitment to equality.[54][55]

By 2020, numerous warnings have been issued that South Africa is heading towards failed state status [56][57][58] with unsustainable government spending, high unemployment, high crime rates, corruption, failing government owned enterprises and collapsing infrastructure.[59][60][61] In 2022, the World Economic Forum said that South Africa risks state collapse and identified five major risks facing the country.[62] The Director-General of the South African Treasury, Dondo Mogajane, has said that, "SA is showing the signs of a failing state more common in countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia".[63] Former minister Jay Naidoo has said that South Africa is in serious trouble and is showing signs of a failed state, with record unemployment levels and the fact that many young people will not find a job in their lifetime.[64] Efficient Group chief economist Dawie Roodt said the country is in deep trouble, "South Africans have been getting poorer for a decade". He said he is very concerned because "32 million people get an income from the state. The state cannot afford this anymore".[65] Neal Froneman, CEO of Sibanye-Stillwater, said that crime is out of control, with 'mafia-style shakedowns' for procurement contracts becoming the norm. "Government leadership has created this problem and they are doing nothing. The government can't deal with it because it goes against their ideology."[66] Professor Eddy Maloka, from the Institute of Risk Management, "The ANC has left us in a mess. They've turned their crisis into ours... Government has collapsed in areas across the country. We are seeing inner-cities collapse and degenerate".[67] Professor David Himbara said that "South Africa is a classic case of a de facto one-party state with mismanaged institutions and endemic crime and corruption".[68] In May 2023, the Executive Chairman of Sygnia, Magda Wierzycka, said that "warnings of South Africa becoming a failed state are lagging reality – we are already there" [69].

^ Wymer, John; Singer, R (1982). The Middle Stone Age at Klasies River Mouth in South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-76103-9. ^ Deacon, HJ (2001). "Guide to Klasies River" (PDF). Stellenbosch University. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009. ^ "Fossil Hominid Sites of South Africa". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019. ^ Broker, Stephen P. "Hominid Evolution". Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2008. ^ Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-395-13592-1. ^ Leakey, Louis Seymour Bazett (1936). "Stone Age cultures of South Africa". Stone age Africa: an outline of prehistory in Africa (reprint ed.). Negro Universities Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780837120225. Retrieved 21 February 2018. In 1929, during a brief visit to the Transvaal, I myself found a number of pebble tools in some of the terrace gravels of the Vaal River, and similar finds have been recorded by Wayland, who visited South Africa, and by van Riet Lowe and other South African prehistorians. ^ Alfred, Luke. "The Bakoni: From prosperity to extinction in a generation". Citypress. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020. ^ "Adam's Calendar in Waterval Boven, Mpumalanga". www.sa-venues.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020. ^ Domville-Fife, C.W. (1900). The encyclopedia of the British Empire the first encyclopedic record of the greatest empire in the history of the world ed. London: Rankin. p. 25. ^ Mackenzie, W. Douglas; Stead, Alfred (1899). South Africa: Its History, Heroes, and Wars. Chicago: The Co-Operative Publishing Company. ^ Pakeman, SA. Nations of the Modern World: Ceylon (1964 ed.). Frederick A Praeger, Publishers. pp. 18–19. ASIN B0000CM2VW. ^ a b c Wilmot, Alexander & John Centlivres Chase. History of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope: From Its Discovery to the Year 1819 (2010 ed.). Claremont: David Philip (Pty) Ltd. pp. 1–548. ISBN 978-1-144-83015-9. ^ Kaplan, Irving. Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa (PDF). pp. 46–771. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015. ^ "African History Timeline". West Chester University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2008. ^ a b Hunt, John (2005). Campbell, Heather-Ann (ed.). Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape, 1652–1708. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–35. ISBN 978-1-904744-95-5. ^ Worden, Nigel (5 August 2010). Slavery in Dutch South Africa (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-0-521-15266-2. ^ a b Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 237–317. ^ a b c d e Stapleton, Timothy (2010). A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid. Santa Barbara: Praeger Security International. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-313-36589-8. ^ Keegan, Timothy (1996). Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order (1996 ed.). David Philip Publishers (Pty) Ltd. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-8139-1735-1. ^ a b c Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1997). The British Empire, 1558–1995. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201–203. ISBN 978-0-19-873133-7. ^ "Shaka: Zulu Chieftain". Historynet.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2011. ^ "Shaka (Zulu chief)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2011. ^ W. D. Rubinstein (2004). Genocide: A History. Pearson Longman. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013. ^ Williams, Garner F (1905). The Diamond Mines of South Africa, Vol II. New York: B. F Buck & Co. pp. Chapter XX. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2008. ^ "South African Military History Society – Journal- THE SEKUKUNI WARS". samilitaryhistory.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020. ^ "5 of the worst atrocities carried out by the British Empire". The Independent. 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019. ^ Ogura, Mitsuo (1996). "Urbanization and Apartheid in South Africa: Influx Controls and Their Abolition". The Developing Economies. 34 (4): 402–423. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1049.1996.tb01178.x. ISSN 1746-1049. PMID 12292280. ^ Bond, Patrick (1999). Cities of gold, townships of coal: essays on South Africa's new urban crisis. Africa World Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-86543-611-4. ^ Report of the Select Committee on Location Act (Report). Cape Times Limited. 1906. Retrieved 30 July 2009. ^ Godley, Godfrey; Archibald, Welsh; Thomson, William; Hemsworth, H. D. (1920). Report of the Inter-departmental committee on the native pass laws (Report). Cape Times Limited. p. 2. ^ Papers relating to legislation affecting natives in the Transvaal (Report). Great Britain Colonial Office; Transvaal (Colony). Governor (1901–1905: Milner). January 1902. ^ De Villiers, John Abraham Jacob (1896). The Transvaal. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 30 (n46). Retrieved 30 July 2009. ^ Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 467. ^ "Native Land Act". South African Institute of Race Relations. 19 June 1913. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. ^ Gloria Galloway, "Chiefs Reflect on Apartheid" Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail, 11 December 2013 ^ Beinart, William (2001). Twentieth-century South Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-19-289318-5. ^ "apartheid | South Africa, Definition, Facts, Beginning, & End | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 15 May 2022. ^ "Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2013. On 5 October 1960 a referendum was held in which White voters were asked: "Do you support a republic for the Union?" – 52 percent voted 'Yes'. ^ Gibson, Nigel; Alexander, Amanda; Mngxitama, Andile (2008). Biko Lives! Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-230-60649-4. ^ Switzer, Les (2000). South Africa's Resistance Press: Alternative Voices in the Last Generation Under Apartheid. Issue 74 of Research in international studies: Africa series. Ohio University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-89680-213-1. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020. ^ Mitchell, Thomas (2008). Native vs Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland and South Africa. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0-313-31357-8. ^ Bridgland, Fred (1990). The War for Africa: Twelve months that transformed a continent. Gibraltar: Ashanti Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-874800-12-5. ^ Landgren, Signe (1989). Embargo Disimplemented: South Africa's Military Industry (1989 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-0-19-829127-5. ^ Cite error: The named reference sach3 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ "Zuma surprised at level of white poverty". Mail & Guardian. 18 April 2008. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2010. ^ "South Africa". Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2007. ^ "2015 United Nations Human Development Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2018. ^ "South African Life Expectancy at Birth, World Bank". Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018. ^ "Ridicule succeeds where leadership failed on AIDS". South African Institute of Race Relations. 10 November 2006.[dead link] ^ a b Chance, Kerry (20 June 2008). "Broke-on-Broke Violence". Slate. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011. ^ "COHRE statement on Xenophobic Attacks". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2011. ^ Southern African Migration Project; Institute for Democracy in South Africa; Queen's University (2008). Jonathan Crush (ed.). The perfect storm: the realities of xenophobia in contemporary South Africa (PDF). Idasa. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-920118-71-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013. ^ a b c d United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR Global Appeal 2011 – South Africa". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2011. ^ Harris, Bronwyn (2004). Arranging prejudice: Exploring hate crime in post-apartheid South Africa. Cape Town. ^ Traum, Alexander (2014). "Contextualising the hate speech debate: the United States and South Africa". The Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa. 47 (1): 64–88. ^ Sguazzin, Anthony (10 September 2020). "South Africa heading towards becoming a failed state: Report". Aljazeera. ^ Sguazzin, Anthony (10 September 2020). "South Africa Heading Toward Becoming a Failed State, Group Says". Bloomberg. ^ "Another warning that South Africa is at risk of becoming a failed state". Retrieved 7 April 2023. ^ "South Africa, Failed State?". www.linkedin.com. ^ "South Africa is slowly collapsing". BusinessTech. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022. ^ "Crime 'worrying' in South Africa: 7,000 murdered in three months". Aljazeera. 23 November 2022. ^ Head, Tom (12 January 2022). "South Africa 'at risk of STATE COLLAPSE' - according to top experts". The South African. ^ Head, Tom (6 March 2022). "SA heading towards 'failed state' territory - according to our own Treasury". The South African. ^ "South Africa showing signs of a failed state". My Broadband. 13 October 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022. ^ "South Africa is in deep trouble, warns economist". My Broadband. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022. ^ "South Africa is practically a failed state: CEO". BusinessTech. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022. ^ Head, Tom (11 April 2022). "'Our cities are collapsing!' - SA identified as 'failing state' by top expert". The South African. ^ "South Africa: A sophisticated failing state". The Africa Report.com. 29 July 2020. ^ https://businesstech.co.za/news/business-opinion/684085/south-africa-is-already-a-failed-state/

- Stay safe

See also the warning about security at O.R. Tambo International Airport.

South Africa has very few earthquakes, cyclones, tornadoes, floods, terrorist incidents or contagious diseases (with the notable exception of HIV).

However, South Africa has some of the highest violent crime rates in the world, though by being vigilant and using common sense, you should have a safe and pleasant trip as millions of other people have each year. The key is to know and stick to general safety precautions: never walk around in deserted areas at night or advertise possession of money or expensive accessories.

Crime levels are relatively high in South Africa, however, perceptions can be misleading because statistically, most of the criminal activity is concentrated around certain specific areas and perpetrated by specialised criminal organizations connected to copper theft, car theft, transportation of goods and cash in transit theft, home or business and warehouse break-ins, smuggling, drug dealing, prostitution and so on. Opportunistic attacks like robberies or muggings of individuals outside those areas are very uncommon unless one mixes with low life characters or ventures into seedy joints or gangster neighborhoods. As far as tourism goes, most embassies and tourist organizations will have lists of known areas to avoid. If you drive around, you'll notice some bad road behaviour, however inconsiderate it may be to you, just ignore it and make sure there isn't a road rage incident. Like anywhere else, as a general rule, it's advisable for visitors to keep valuables out of sight and to keep a low profile. All South Africans are in general a nice bunch of people but as in any society, there's always a couple of bad apples mixed in the barrel.

...Read moreStay safeRead lessSee also the warning about security at O.R. Tambo International Airport.

South Africa has very few earthquakes, cyclones, tornadoes, floods, terrorist incidents or contagious diseases (with the notable exception of HIV).

However, South Africa has some of the highest violent crime rates in the world, though by being vigilant and using common sense, you should have a safe and pleasant trip as millions of other people have each year. The key is to know and stick to general safety precautions: never walk around in deserted areas at night or advertise possession of money or expensive accessories.

Crime levels are relatively high in South Africa, however, perceptions can be misleading because statistically, most of the criminal activity is concentrated around certain specific areas and perpetrated by specialised criminal organizations connected to copper theft, car theft, transportation of goods and cash in transit theft, home or business and warehouse break-ins, smuggling, drug dealing, prostitution and so on. Opportunistic attacks like robberies or muggings of individuals outside those areas are very uncommon unless one mixes with low life characters or ventures into seedy joints or gangster neighborhoods. As far as tourism goes, most embassies and tourist organizations will have lists of known areas to avoid. If you drive around, you'll notice some bad road behaviour, however inconsiderate it may be to you, just ignore it and make sure there isn't a road rage incident. Like anywhere else, as a general rule, it's advisable for visitors to keep valuables out of sight and to keep a low profile. All South Africans are in general a nice bunch of people but as in any society, there's always a couple of bad apples mixed in the barrel.

Do not accept offers from friendly strangers. Do not wear a tummy bag with all your valuables; consider a concealed money belt worn under your shirt instead. Leave passports and other valuables in a safe or other secure location. Although most banks and exchange bureaus require your passport in order to exchange foreign monies to Rands, in South Africa it's legal to carry authenticated photocopies of documents in lieu of originals. To get documents authenticated free of charge, take the original and copies to any South African Police station and ask the officer on duty to help you. The papers will be good for 90 days from police stamp date. Do not carry large sums of money. Do not walk at night through deserted places. Hide that you are a tourist: conceal your camera and binoculars. Do not leave your valuables in plain sight when driving in your car, as "smash and grab" attacks sometimes occur at certain hot spot intersections, and keep your car doors locked and your windows open less than half way. Know where to go so that you avoid getting lost or needing a map: that will avoid signs.

If you are carrying bags, try to hook them under a table or chair leg when sitting down, as this will prevent them from being snatched.

Visiting the townships is possible, but do not do it alone unless you really know where you're going. Some townships are safe while others can be extremely dangerous. Go with an experienced guide. Some tour companies offer perfectly safe guided visits to the townships.

Taking an evening stroll or walking to venues after dark can be very risky. It simply is not part of the culture there, as it is in Europe, North America or Australia. It is best to take a taxi (a metered cab, not a minibus taxi) or private vehicle for an "evening out". The same applies to picking up hitchhikers or offering assistance at broken-down car scenes. It is best to ignore anyone who appears to be in distress at the side of the road as it could be part of a scam. Keep going until you see a police station and tell them about what you have seen.

If you are driving in South Africa, when police officers stop you to check your licence, and you show them an overseas driver's licence, they may come out with some variant of `Have you got written permission from [random government department] to drive in our country?' If your licence is written in English or you have an International Driving Permit then they can't do anything. Stand your ground and state this fact - be polite, courteous and don't pay any money (bribes). Furthermore, any foreign drivers license with English on it is valid in South Africa for ninety days from day of entry, and the corresponding passport may need to be presented together. After ninety days, a foreign drivers licence maybe deemed invalid and need to be converted to a SA driver licence, as the legal status of such foreigners may fall within the temporary resident requirements.

Take extra care when driving at night. Unlike in Europe and North America, vast stretches of South African roads, especially in rural areas, are poorly lit or often completely unlit. This includes highways. Be extra careful as wildlife and people often walk in the middle of the road in smaller towns (not cities like Pretoria, Johannesburg, or Cape Town). You must also take extra care when driving in South Africa due to the risk of carjackings.

Important telephone numbersThe National Tourism Information and Safety Line, ☏ +27 83 123 2345 (mobile). Operated by South African Tourism The National Sea Rescue Institute, ☏ +27 21 434-4011, +27 82 380 3800 (Mobile after hours). A volunteer organization with rescue stations around the coast and mayor inland bodies of waterFrom a fixed line 107 - Emergency (in Cape Town, only from fixed lines) 10111 - Police 10177 - AmbulanceFrom a mobile phone 112-All EmergenciesInternational calls at local rates Step 1: Dial: 087 150 0823 from any mobile or landline Step 2: Dial destination number and press # e.g. 00 44 11 123 4567 # Countries: USA, UK (landline), India, Bangladesh, China, Hong Kong and many more. Supported on: Vodacom, MTN, Cell C, Telkom and NeotelWildlife Road signs will remind about emergency numbers

Road signs will remind about emergency numbers Meerkats are on the lookout at Tswalu Kalahari Reserve

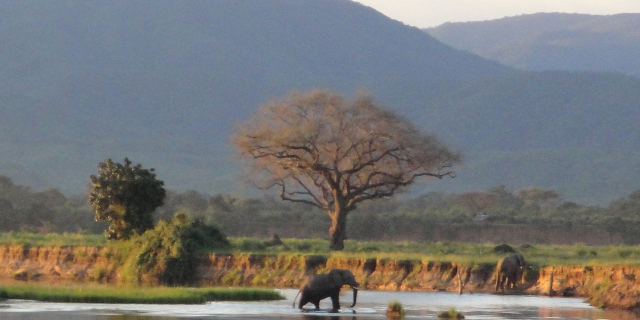

Meerkats are on the lookout at Tswalu Kalahari ReserveOne of the main reasons travellers visit South Africa is to experience the outdoors and see the wide range of wildlife.

When driving in a wildlife reserve, always keep to the speed limits and stay inside your car at all times. On game drives or walks, always follow the instructions of your guide.

Do not drive too close to elephants. Be prepared to back up very quickly if they charge at you. Elephants are strong enough to roll many small cars. They can destroy small cars by sitting on them (which means they blow out all tires and windows and bend the frame beyond repair) while you scream for your life inside.

Ensure that you wear socks and boots whenever you are walking in the bush; do not wear open sandals. A good pair of boots can stop snake and insect bites and avoid any possible cuts that may lead to infections.

In many areas you may encounter wildlife while driving on public roads, monkeys and baboons are especially common. Do not get out of the vehicle to take photos or otherwise try to interact with the animals. These are wild animals and their actions can be unpredictable.

Sometimes you might find yourself in the open with wild animals (often happens with baboons at Cape Point). Keep your distance and always ensure that the animals are only to one side of you, do not walk between two groups or individuals. A female baboon may get rather upset if you separate her from her child.

Always check with locals before swimming in a river or lake as there may be crocodiles or hippos. Most major beaches in KwaZulu-Natal have shark nets installed. If you intend to swim anywhere other that the main beaches, check with a local first.

Shark nets may be removed for a couple of days during the annual sardine run (normally along the KwaZulu-Natal coast between early May and late July). This is done to avoid excessive shark and other marine life fatalities. Notices are posted on beaches during these times.