Italia

ItalyContext of Italy

Italy (Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja] (listen)), officially the Italian Republic or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern and Western Europe. Located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, it consists of a peninsula delimited by the Alps and surrounded by several islands; its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical region. Italy shares land borders with France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia and the enclaved microstates of Vatican City and San Marino. It has a territorial exclave in Switzerland, Campione, and some islands in the African Plate. Italy covers an area of 301,230 km2 (116,310 sq mi), with a population of about 60 million. It is the third-most populous member state of the European Union, the sixth-most po...Read more

Italy (Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja] (listen)), officially the Italian Republic or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern and Western Europe. Located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, it consists of a peninsula delimited by the Alps and surrounded by several islands; its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical region. Italy shares land borders with France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia and the enclaved microstates of Vatican City and San Marino. It has a territorial exclave in Switzerland, Campione, and some islands in the African Plate. Italy covers an area of 301,230 km2 (116,310 sq mi), with a population of about 60 million. It is the third-most populous member state of the European Union, the sixth-most populous country in Europe, and the tenth-largest country in the continent by land area. Italy's capital and largest city is Rome.

Italy was the native place of civilizations such as the Italic peoples and the Etruscans, while due to its central geographic location in Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, the country has also historically been home to myriad peoples and cultures, who immigrated to the peninsula throughout history. The Latins, native of central Italy, formed the Roman Kingdom in the 8th century BC, which eventually became a republic with a government of the Senate and the People. The Roman Republic initially conquered and assimilated its neighbours on the Italian peninsula, eventually expanding and conquering a large part of Europe, North Africa and Western Asia. By the first century BC, the Roman Empire emerged as the dominant power in the Mediterranean Basin and became a leading cultural, political and religious centre, inaugurating the Pax Romana, a period of more than 200 years during which Italy's law, technology, economy, art, and literature developed.

During the Early Middle Ages, Italy endured the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Barbarian Invasions, but by the 11th century, numerous city-states and maritime republics, mostly in the North, became prosperous through trade, commerce, and banking, laying the groundwork for modern capitalism. The Renaissance began in Italy and spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration, and art. During the Middle Ages, Italian explorers discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. However, centuries of rivalry and infighting between the Italian city-states, and the invasions of other European powers during the Italian Wars of the 15th and 16th centuries, left Italy politically fragmented. Italy's commercial and political power significantly waned during the 17th and 18th centuries with the decline of the Catholic Church and the increasing importance of trade routes that bypassed the Mediterranean.

By the mid-19th century, rising Italian nationalism, along with other social, economic, and military events, led to a period of revolutionary political upheaval. After centuries of political and territorial divisions, Italy was almost entirely unified in 1861 following a war of independence, establishing the Kingdom of Italy. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Italy rapidly industrialised, mainly in the north, and acquired a colonial empire, while the south remained largely impoverished and excluded from industrialisation, fuelling a large and influential diaspora. Despite being one of the victorious allied powers in World War I, Italy entered a period of economic crisis and social turmoil, leading to the rise of the Italian fascist dictatorship in 1922. The participation of Italy in World War II on the Axis led to the Italian surrender to Allied powers and its occupation by Nazi Germany helped by Fascists, followed by the rise of the Italian Resistance and the subsequent Italian Civil War and liberation of Italy. After the war, the country abolished its monarchy, established a democratic unitary parliamentary republic, and enjoyed a prolonged economic boom, becoming a major advanced economy.

Italy has the eighth-largest nominal GDP (third in the European Union) in the world, the ninth-largest national wealth and the third-largest central bank gold reserve. The country is a great power, and it has a significant role in regional and global economic, military, cultural, and diplomatic affairs. Italy is a founding and leading member of the European Union and a member of numerous international institutions, including the United Nations, NATO, the OECD, the G7, the Latin Union, the Schengen Area, and many more. The source of many inventions and discoveries, the country is considered a cultural superpower and has long been a global centre of art, music, literature, philosophy, science and technology, tourism and fashion, as well as having greatly influenced and contributed to diverse fields including cinema, cuisine, sports, jurisprudence, banking, and business. It has the world's largest number of World Heritage Sites (58), and is the world's fifth-most visited country.

More about Italy

- Currency Euro

- Native name Italia

- Calling code +39

- Internet domain .it

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 7.74

- Population 58850717

- Area 302068

- Driving side right

- Prehistory and antiquity...Read morePrehistory and antiquityRead less

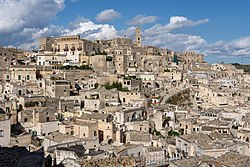

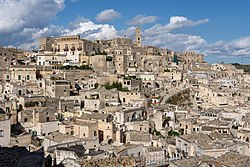

The Sassi cave houses of Matera are believed to be among the first human settlements in Italy dating back to the Paleolithic.[1]

The Sassi cave houses of Matera are believed to be among the first human settlements in Italy dating back to the Paleolithic.[1] Etruscan fresco in the Monterozzi necropolis, 5th century BC

Etruscan fresco in the Monterozzi necropolis, 5th century BCThousands of Lower Paleolithic artefacts have been recovered from Monte Poggiolo, dating as far back as 850,000 years.[2] Excavations throughout Italy revealed a Neanderthal presence dating back to the Middle Palaeolithic period some 200,000 years ago,[3] while modern humans appeared about 40,000 years ago at Riparo Mochi.[4] Archaeological sites from this period include Addaura cave, Altamura, Ceprano, and Gravina in Puglia.[5]

The Ancient peoples of pre-Roman Italy – such as the Umbrians, the Latins (from which the Romans emerged), Volsci, Oscans, Samnites, Sabines, the Celts, the Ligures, the Veneti, the Iapygians, and many others – were Indo-European peoples, most of them specifically of the Italic group. The main historic peoples of possible non-Indo-European or pre-Indo-European heritage include the Etruscans of central and northern Italy, the Elymians and the Sicani in Sicily, and the prehistoric Sardinians, who gave birth to the Nuragic civilisation. Other ancient populations being of undetermined language families and of possible non-Indo-European origin include the Rhaetian people and Cammuni, known for their rock carvings in Valcamonica, the largest collections of prehistoric petroglyphs in the world.[6] A well-preserved natural mummy known as Ötzi the Iceman, determined to be 5,000 years old (between 3400 and 3100 BCE, Copper Age), was discovered in the Similaun glacier of South Tyrol in 1991.[7]

The first foreign colonisers were the Phoenicians, who initially established colonies and founded various emporiums on the coasts of Sicily and Sardinia. Some of these soon became small urban centres and were developed parallel to the ancient Greek colonies; among the main centres there were the cities of Motya, Zyz (modern Palermo), Soluntum in Sicily, and Nora, Sulci, and Tharros in Sardinia.[8]

Between the 17th and the 11th centuries BC Mycenaean Greeks established contacts with Italy[9][10][11] and in the 8th and 7th centuries BC a number of Greek colonies were established all along the coast of Sicily and the southern part of the Italian Peninsula, that became known as Magna Graecia.[12]

Ionian settlers founded Elaia, Kyme, Rhegion, Naxos, Zankles, Hymera, and Katane. Doric colonists founded Taras, Syrakousai, Megara Hyblaia, Leontinoi, Akragas, Ghelas; the Syracusans founded Ankón and Adria; the megarese founded Selinunte. The Achaeans founded Sybaris, Poseidonia, Kroton, Lokroi Epizephyrioi, and Metapontum; tarantini and thuriots found Herakleia. The Greek colonization placed the Italic peoples in contact with democratic forms of government and with high artistic and cultural expressions.[13]

Ancient Rome The Colosseum in Rome, built c. 70–80 AD, is considered one of the greatest works of architecture and engineering of ancient history.

The Colosseum in Rome, built c. 70–80 AD, is considered one of the greatest works of architecture and engineering of ancient history. The Roman Empire at its greatest extent, 117 AD

The Roman Empire at its greatest extent, 117 ADRome, a settlement around a ford on the river Tiber in central Italy conventionally founded in 753 BC, was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. In 509 BC, the Romans expelled the last king from their city, favouring a government of the Senate and the People (SPQR) and establishing an oligarchic republic.

The Italian Peninsula, named Italia, was consolidated into a single entity during the Roman expansion and conquest of new lands at the expense of the other Italic tribes, Etruscans, Celts, and Greeks. A permanent association with most of the local tribes and cities was formed, and Rome began the conquest of Western Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East. In the wake of Julius Caesar's rise and death in the first century BC, Rome grew over the course of centuries into a massive empire stretching from Britain to the borders of Persia, and engulfing the whole Mediterranean basin, in which Greek and Roman and many other cultures merged into a unique civilisation. The long and triumphant reign of the first emperor, Augustus, began a golden age of peace and prosperity. Roman Italy remained the metropole of the empire, and as the homeland of the Romans and the territory of the capital, maintained a special status which made it Domina Provinciarum ("ruler of the provinces", the latter being all the remaining territories outside Italy).[14][15][16] More than two centuries of stability followed, during which Italy was referred to as the Rectrix Mundi ("governor of the world") and Omnium Terrarum Parens ("parent of all lands").[17]

The Roman Empire was among the most powerful economic, cultural, political and military forces in the world of its time, and it was one of the largest empires in world history. At its height under Trajan, it covered 5 million square kilometres.[18][19] The Roman legacy has deeply influenced Western civilisation, shaping most of the modern world; among the many legacies of Roman dominance are the widespread use of the Romance languages derived from Latin, the numerical system, the modern Western alphabet and calendar, and the emergence of Christianity as a major world religion.[20] The Indo-Roman trade relations, beginning around the 1st century BCE, testify to extensive Roman trade in far away regions; many reminders of the commercial trade between the Indian subcontinent and Italy have been found, such as the ivory statuette Pompeii Lakshmi from the ruins of Pompeii.

In a slow decline since the third century AD, the Empire split in two in 395 AD. The Western Empire, under the pressure of the barbarian invasions, eventually dissolved in 476 AD when its last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chief Odoacer. The Eastern half of the Empire survived for another thousand years.

Middle Ages The Lombard Kingdom (blue) at its greatest extent, under King Aistulf (749–756). Territories controlled by the Byzantine Empire are marked in orange.

The Lombard Kingdom (blue) at its greatest extent, under King Aistulf (749–756). Territories controlled by the Byzantine Empire are marked in orange.After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy fell under the power of Odoacer's kingdom, and, later, was seized by the Ostrogoths,[21] followed in the 6th century by a brief reconquest under Byzantine Emperor Justinian. The invasion of another Germanic tribe, the Lombards, late in the same century, reduced the Byzantine presence to the rump realm of the Exarchate of Ravenna and started the end of political unity of the peninsula for the next 1,300 years. The peninsula was therefore divided as follows: northern Italy and Tuscany formed the Lombard kingdom, with its capital in Pavia, while in central-southern Italy the Lombards controlled the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. The remaining part of the peninsula remained under the Byzantines and was divided between the exarchate of Italy, based in Ravenna, the Duchy of Rome, the Duchy of Naples, the Duchy of Calabria and Sicily, the latter directly dependent on the Emperor of Constantinople.[22] Invasions of the peninsula caused a chaotic succession of barbarian kingdoms and the so-called "dark ages". The Lombard kingdom was subsequently absorbed into the Frankish Empire by Charlemagne in the late 8th century and became the Kingdom of Italy.[23] The Franks also helped the formation of the Papal States in central Italy. Until the 13th century, Italian politics was dominated by the relations between the Holy Roman Emperors and the Papacy, with most of the Italian city-states siding with the former (Ghibellines) or with the latter (Guelphs) for momentary convenience.[24]

Marco Polo, explorer of the 13th century, recorded his 24 years-long travels in the Book of the Marvels of the World, introducing Europeans to Central Asia and China.[25]

Marco Polo, explorer of the 13th century, recorded his 24 years-long travels in the Book of the Marvels of the World, introducing Europeans to Central Asia and China.[25]The Germanic Emperor and the Roman Pontiff became the universal powers of medieval Europe. However, the conflict over the investiture controversy (a conflict between two radically different views of whether secular authorities such as kings, counts, or dukes, had any legitimate role in appointments to ecclesiastical offices) and the clash between Guelphs and Ghibellines led to the end of the Imperial-feudal system in the north of Italy where city-states gained independence. It was during this chaotic era that Italian towns saw the rise of a peculiar institution, the medieval commune. Given the power vacuum caused by extreme territorial fragmentation and the struggle between the Empire and the Holy See, local communities sought autonomous ways to maintain law and order.[26] The investiture controversy was finally resolved by the Concordat of Worms. In 1176 a league of city-states, the Lombard League, defeated the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano, thus ensuring effective independence for most of northern and central Italian cities.

Italian city-states such as Milan, Florence and Venice played a crucial innovative role in financial development, devising the main instruments and practices of banking and the emergence of new forms of social and economic organization.[27] In coastal and southern areas, the maritime republics grew to eventually dominate the Mediterranean and monopolise trade routes to the Orient. They were independent thalassocratic city-states, though most of them originated from territories once belonging to the Byzantine Empire. All these cities during the time of their independence had similar systems of government in which the merchant class had considerable power. Although in practice these were oligarchical, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy, the relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.[28] The four best known maritime republics were Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi; the others were Ancona, Gaeta, Noli, and Ragusa.[29][30][31] Each of the maritime republics had dominion over different overseas lands, including many Mediterranean islands (especially Sardinia and Corsica), lands on the Adriatic, Aegean, and Black Sea (Crimea), and commercial colonies in the Near East and in North Africa. Venice maintained enormous tracts of land in Greece, Cyprus, Istria, and Dalmatia until as late as the mid-17th century.[32]

Left: flag of the modern Italian Navy, displaying the coat of arms of Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi, the most prominent maritime republics

Right: trade routes and colonies of the Genoese (red) and Venetian (green) empiresVenice and Genoa were Europe's main gateways to trade with the East, and producers of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of silk, wool, banking, and jewellery. The wealth such business brought to Italy meant that large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned. The republics were heavily involved in the Crusades, providing support and transport, but most especially taking advantage of the political and trading opportunities resulting from these wars.[28] Italy first felt the huge economic changes in Europe which led to the commercial revolution: the Republic of Venice was able to defeat the Byzantine Empire and finance the voyages of Marco Polo to Asia; the first universities were formed in Italian cities, and scholars such as Thomas Aquinas obtained international fame; Frederick I of Sicily made Italy the political-cultural centre of a reign that temporarily included the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Jerusalem; capitalism and banking families emerged in Florence, where Dante and Giotto were active around 1300.[33]

In the south, Sicily had become an Islamic emirate in the 9th century, thriving until the Italo-Normans conquered it in the late 11th century together with most of the Lombard and Byzantine principalities of southern Italy.[34] Through a complex series of events, southern Italy developed as a unified kingdom, first under the House of Hohenstaufen, then under the Capetian House of Anjou and, from the 15th century, the House of Aragon. In Sardinia, the former Byzantine provinces became independent states known in Italian as Judicates, although some parts of the island fell under Genoese or Pisan rule until eventual Aragonese annexation in the 15th century. The Black Death pandemic of 1348 left its mark on Italy by killing perhaps one third of the population.[35][36] However, the recovery from the plague led to a resurgence of cities, trade, and economy, which allowed the blossoming of Humanism and Renaissance that later spread to Europe.

Early Modern The Italian states before the beginning of the Italian Wars in 1494

The Italian states before the beginning of the Italian Wars in 1494Italy was the birthplace and heart of the Renaissance during the 1400s and 1500s. The Italian Renaissance marked the transition from the medieval period to the modern age as Europe recovered, economically and culturally, from the crises of the Late Middle Ages and entered the Early Modern Period. The Italian polities were now regional states effectively ruled by Princes, de facto monarchs in control of trade and administration, and their courts became major centres of the Arts and Sciences. The Italian princedoms represented a first form of modern states as opposed to feudal monarchies and multinational empires. The princedoms were led by political dynasties and merchant families such as the Medici in Florence, the Visconti and Sforza in the Duchy of Milan, the Doria in the Republic of Genoa, the Loredan, Mocenigo and Barbarigo in the Republic of Venice, the Este in Ferrara, and the Gonzaga in Mantua.[37][38] The Renaissance was therefore a result of the wealth accumulated by Italian merchant cities combined with the patronage of its dominant families.[37] Italian Renaissance exercised a dominant influence on subsequent European painting and sculpture for centuries afterwards, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giotto, Donatello, and Titian, and architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Donato Bramante.

Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance man, in a self-portrait (ca. 1512, Royal Library, Turin)

Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance man, in a self-portrait (ca. 1512, Royal Library, Turin)Following the conclusion of the western schism in favour of Rome at the Council of Constance (1415–1417), the new Pope Martin V returned to the Papal States after a three years-long journey that touched many Italian cities and restored Italy as the sole centre of Western Christianity. During the course of this voyage, the Medici Bank was made the official credit institution of the Papacy, and several significant ties were established between the Church and the new political dynasties of the peninsula. The Popes' status as elective monarchs turned the conclaves and consistories of the Renaissance into political battles between the courts of Italy for primacy in the peninsula and access to the immense resources of the Catholic Church. In 1439, Pope Eugenius IV and the Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaiologos signed a reconciliation agreement between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence hosted by Cosimo the old de Medici. In 1453, Italian forces under Giovanni Giustiniani were sent by Pope Nicholas V to defend the Walls of Constantinople but the decisive battle was lost to the more advanced Turkish army equipped with cannons, and Byzantium fell to Sultan Mehmed II.

The fall of Constantinople led to the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy, fueling the rediscovery of Greco-Roman Humanism.[39][40][41] Humanist rulers such as Federico da Montefeltro and Pope Pius II worked to establish ideal cities where man is the measure of all things, and therefore founded Urbino and Pienza respectively. Pico della Mirandola wrote the Oration on the Dignity of Man, considered the manifesto of Renaissance Humanism, in which he stressed the importance of free will in human beings. The humanist historian Leonardo Bruni was the first to divide human history in three periods: Antiquity, Middle Ages and Modernity.[42] The second consequence of the Fall of Constantinople was the beginning of the Age of Discovery.

Christopher Columbus leads an expedition to the New World, 1492. His voyages are celebrated as the discovery of the Americas from a European perspective, and they opened a new era in the history of humankind and sustained contact between the two worlds.

Christopher Columbus leads an expedition to the New World, 1492. His voyages are celebrated as the discovery of the Americas from a European perspective, and they opened a new era in the history of humankind and sustained contact between the two worlds.Italian[note 1] explorers and navigators from the dominant maritime republics, eager to find an alternative route to the Indies in order to bypass the Ottoman Empire, offered their services to monarchs of Atlantic countries and played a key role in ushering the Age of Discovery and the European colonization of the Americas. The most notable among them were: Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo), colonizer in the name of Spain, who is credited with discovering the New World and the opening of the Americas for conquest and settlement by Europeans;[43] John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto), sailing for England, who was the first European to set foot in "New Found Land" and explore parts of the North American continent in 1497;[44] Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for Portugal, who first demonstrated in about 1501 that the New World (in particular Brazil) was not Asia as initially conjectured, but a fourth continent previously unknown to people of the Old World (America is named after him);[45] and Giovanni da Verrazzano, at the service of France, renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between Florida and New Brunswick in 1524.[46]

Following the fall of Constantinople, the wars in Lombardy came to an end and a defensive alliance known as Italic League was formed between Venice, Naples, Florence, Milan, and the Papacy. Lorenzo the Magnificent de Medici was the greatest Florentine patron of the Renaissance and supporter of the Italic League. He notably avoided the collapse of the League in the aftermath of the Pazzi Conspiracy and during the aborted invasion of Italy by the Turks. However, the military campaign of Charles VIII of France in Italy caused the end of the Italic League and initiated the Italian Wars between the Valois and the Habsburgs. During the High Renaissance of the 1500s, Italy was therefore both the main European battleground and the cultural-economic centre of the continent. Popes such as Julius II (1503–1513) fought for the control of Italy against foreign monarchs, others such as Paul III (1534–1549) preferred to mediate between the European powers in order to secure peace in Italy. In the middle of this conflict, the Medici popes Leo X (1513–1521) and Clement VII (1523–1534) opposed the Protestant reformation and advanced the interests of their family. In 1559, at the end of the French invasions of Italy and of the Italian wars, the many states of northern Italy remained part of the Holy Roman Empire, indirectly subject to the Austrian Habsburgs, while all of Southern Italy (Naples, Sicily, Sardinia) and Milan were under Spanish Habsburg rule.

Flag of the Cispadane Republic, which was the first Italian tricolour adopted by a sovereign Italian state (1797)

Flag of the Cispadane Republic, which was the first Italian tricolour adopted by a sovereign Italian state (1797)The Papacy remained a powerful force and launched the Counter-reformation. Key events of the period include: the Council of Trent (1545–1563); the excommunication of Elizabeth I (1570) and the Battle of Lepanto (1571), both occurring during the pontificate of Pius V; the construction of the Gregorian observatory, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, and the Jesuit China mission of Matteo Ricci under Pope Gregory XIII; the French Wars of Religion; the Long Turkish War and the execution of Giordano Bruno in 1600, under Pope Clement VIII; the birth of the Lyncean Academy of the Papal States, of which the main figure was Galileo Galilei (later put on trial); the final phases of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) during the pontificates of Urban VIII and Innocent X; and the formation of the last Holy League by Innocent XI during the Great Turkish War.

The Italian economy declined during the 1600s and 1700s, as the peninsula was excluded from the rising Atlantic slave trade. Following the European wars of succession of the 18th century, the south passed to a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons and the North fell under the influence of the Habsburg-Lorraine of Austria. During the Coalition Wars, northern-central Italy was reorganised by Napoleon in a number of Sister Republics of France and later as a Kingdom of Italy in personal union with the French Empire.[47] The southern half of the peninsula was administered by Joachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law, who was crowned as King of Naples. The 1814 Congress of Vienna restored the situation of the late 18th century, but the ideals of the French Revolution could not be eradicated, and soon re-surfaced during the political upheavals that characterised the first part of the 19th century.

During the Napoleonic era, in 1797, the first official adoption of the Italian tricolour as a national flag by a sovereign Italian state, the Cispadane Republic, a Napoleonic sister republic of Revolutionary France, took place, on the basis of the events following the French Revolution (1789–1799) which, among its ideals, advocated the national self-determination.[48][49] This event is celebrated by the Tricolour Day.[50] The Italian national colours appeared for the first time on a tricolour cockade in 1789,[51] anticipating by seven years the first green, white and red Italian military war flag, which was adopted by the Lombard Legion in 1796.[52]

Unification

Giuseppe Mazzini (left), highly influential leader of the Italian revolutionary movement; and Giuseppe Garibaldi (right), celebrated as one of the greatest generals of modern times[53] and as the "Hero of the Two Worlds",[54] who commanded and fought in many military campaigns that led to Italian unification

Giuseppe Mazzini (left), highly influential leader of the Italian revolutionary movement; and Giuseppe Garibaldi (right), celebrated as one of the greatest generals of modern times[53] and as the "Hero of the Two Worlds",[54] who commanded and fought in many military campaigns that led to Italian unificationThe birth of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the political and social Italian unification movement, or Risorgimento, emerged to unite Italy consolidating the different states of the peninsula and liberate it from foreign control. A prominent radical figure was the patriotic journalist Giuseppe Mazzini, member of the secret revolutionary society Carbonari and founder of the influential political movement Young Italy in the early 1830s, who favoured a unitary republic and advocated a broad nationalist movement. His prolific output of propaganda helped the unification movement stay active.

In this context, in 1847, the first public performance of the song Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946, took place.[55][56] Il Canto degli Italiani, written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro, is also known as the Inno di Mameli, after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d'Italia, from its opening line.

Holographic copy of 1847 of Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946

Holographic copy of 1847 of Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946The most famous member of Young Italy was the revolutionary and general Giuseppe Garibaldi, renowned for his extremely loyal followers,[57] who led the Italian republican drive for unification in Southern Italy. However, the Northern Italy monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state. In the context of the 1848 liberal revolutions that swept through Europe, an unsuccessful first war of independence was declared on Austria. In 1855, the Kingdom of Sardinia became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War, giving Cavour's diplomacy legitimacy in the eyes of the great powers.[58][59] The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating Lombardy. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy,[60] and the Niçard Vespers.

Animated map of the Italian unification from 1829 to 1871

Animated map of the Italian unification from 1829 to 1871In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led the drive for unification in Naples and Sicily (the Expedition of the Thousand),[61] while the House of Savoy troops occupied the central territories of the Italian peninsula, except Rome and part of Papal States. Teano was the site of the famous meeting of 26 October 1860 between Giuseppe Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II, last King of Sardinia, in which Garibaldi shook Victor Emanuel's hand and hailed him as King of Italy; thus, Garibaldi sacrificed republican hopes for the sake of Italian unity under a monarchy. Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's Southern Italy allowing it to join the union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. This allowed the Sardinian government to declare a united Italian kingdom on 17 March 1861.[62] Victor Emmanuel II then became the first king of a united Italy, and the capital was moved from Turin to Florence.

In 1866, Victor Emmanuel II allied with Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War, waging the Third Italian War of Independence which allowed Italy to annexe Venetia. Finally, in 1870, as France abandoned its garrisons in Rome during the disastrous Franco-Prussian War to keep the large Prussian Army at bay, the Italians rushed to fill the power gap by taking over the Papal States. Italian unification was completed and shortly afterwards Italy's capital was moved to Rome. Victor Emmanuel, Garibaldi, Cavour, and Mazzini have been referred as Italy's Four Fathers of the Fatherland.[53]

Liberal period

Victor Emmanuel II (left) and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour (right), leading figures in the Italian unification, became respectively the first king and first Prime Minister of unified Italy.

Victor Emmanuel II (left) and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour (right), leading figures in the Italian unification, became respectively the first king and first Prime Minister of unified Italy.The new Kingdom of Italy obtained Great Power status. The Constitutional Law of the Kingdom of Sardinia the Albertine Statute of 1848, was extended to the whole Kingdom of Italy in 1861, and provided for basic freedoms of the new State, but electoral laws excluded the non-propertied and uneducated classes from voting. The government of the new kingdom took place in a framework of parliamentary constitutional monarchy dominated by liberal forces. As Northern Italy quickly industrialised, the South and rural areas of the North remained underdeveloped and overpopulated, forcing millions of people to migrate abroad and fuelling a large and influential diaspora. The Italian Socialist Party constantly increased in strength, challenging the traditional liberal and conservative establishment.

Starting in the last two decades of the 19th century, Italy developed into a colonial power by forcing under its rule Eritrea and Somalia in East Africa, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in North Africa (later unified in the colony of Libya) and the Dodecanese islands.[63] From 2 November 1899 to 7 September 1901, Italy also participated as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion in China; on 7 September 1901, a concession in Tientsin was ceded to the country, and on 7 June 1902, the concession was taken into Italian possession and administered by a consul. In 1913, male universal suffrage was adopted. The pre-war period dominated by Giovanni Giolitti, Prime Minister five times between 1892 and 1921, was characterised by the economic, industrial, and political-cultural modernization of Italian society.

The Victor Emmanuel II Monument in Rome, a national symbol of Italy celebrating the first king of the unified country, and resting place of the Italian Unknown Soldier since the end of World War I. It was inaugurated in 1911, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Unification of Italy.

The Victor Emmanuel II Monument in Rome, a national symbol of Italy celebrating the first king of the unified country, and resting place of the Italian Unknown Soldier since the end of World War I. It was inaugurated in 1911, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Unification of Italy.Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[64] in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the First Italian War of Independence.[65][66]

Italy, nominally allied with the German Empire and the Empire of Austria-Hungary in the Triple Alliance, in 1915 joined the Allies into World War I with a promise of substantial territorial gains, that included western Inner Carniola, former Austrian Littoral, Dalmatia as well as parts of the Ottoman Empire. The country gave a fundamental contribution to the victory of the conflict as one of the "Big Four" top Allied powers. The war on the Italian Front was initially inconclusive, as the Italian army got stuck in a long attrition war in the Alps, making little progress and suffering heavy losses. However, the reorganization of the army and the conscription of the so-called '99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99, all males born in 1899 who were turning 18) led to more effective Italian victories in major battles, such as on Monte Grappa and in a series of battles on the Piave river. Eventually, in October 1918, the Italians launched a massive offensive, culminating in the victory of Vittorio Veneto. The Italian victory,[67][68][69] which was announced by the Bollettino della Vittoria and the Bollettino della Vittoria Navale, marked the end of the war on the Italian Front, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was chiefly instrumental in ending the First World War less than two weeks later. Italian armed forces were also involved in the African theatre, the Balkan theatre, the Middle Eastern theatre, and then took part in the Occupation of Constantinople.

During the war, more than 650,000 Italian soldiers and as many civilians died,[70] and the kingdom went to the brink of bankruptcy. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) and the Treaty of Rapallo (1920) allowed the annexation of Trentino Alto-Adige, Julian March, Istria, Kvarner as well as the Dalmatian city of Zara. The subsequent Treaty of Rome (1924) led to the annexation of the city of Fiume to Italy. Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Treaty of London (1915), so this outcome was denounced as a Mutilated victory. The rhetoric of Mutilated victory was adopted by Benito Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy. Historians regard Mutilated victory as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.[71] Italy also gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council.

Fascist regime The fascist dictator Benito Mussolini titled himself Duce and ruled the country from 1922 to 1943.

The fascist dictator Benito Mussolini titled himself Duce and ruled the country from 1922 to 1943.The socialist agitations that followed the devastation of the Great War, inspired by the Russian Revolution, led to counter-revolution and repression throughout Italy. The liberal establishment, fearing a Soviet-style revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party, led by Benito Mussolini. In October 1922 the Blackshirts of the National Fascist Party attempted a mass demonstration and a coup named the "March on Rome" which failed but at the last minute, King Victor Emmanuel III refused to proclaim a state of siege and appointed Mussolini prime minister, thereby transferring political power to the fascists without armed conflict.[72][73] Over the next few years, Mussolini banned all political parties and curtailed personal liberties, thus forming a dictatorship. These actions attracted international attention and eventually inspired similar dictatorships such as Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain.

Italian Fascism is based upon Italian nationalism and imperialism, and in particular seeks to complete what it considers as the incomplete project of the unification of Italy by incorporating Italia Irredenta (unredeemed Italy) into the state of Italy.[74][75] To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that Dalmatia was a land of Italian culture whose Italians, including those of Italianized South Slavic descent, had been driven out of Dalmatia and into exile in Italy, and supported the return of Italians of Dalmatian heritage.[76] Mussolini identified Dalmatia as having strong Italian cultural roots for centuries, similarly to Istria, via the Roman Empire and the Republic of Venice.[77] To the south of Italy, the Fascists claimed Malta, which belonged to the United Kingdom, and Corfu, which instead belonged to Greece; to the north claimed Italian Switzerland, while to the west claimed Corsica, Nice, and Savoy, which belonged to France.[78][79] The Fascist regime produced literature on Corsica that presented evidence of the island's italianità.[80] The Fascist regime produced literature on Nice that justified that Nice was an Italian land based on historic, ethnic, and linguistic grounds.[80]

Areas controlled by the Italian Empire during its existenceKingdom of ItalyColonies of ItalyProtectorates and areas occupied during World War II

Areas controlled by the Italian Empire during its existenceKingdom of ItalyColonies of ItalyProtectorates and areas occupied during World War IIThe Armistice of Villa Giusti, which ended fighting between Italy and Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I, resulted in Italian annexation of neighbouring parts of Yugoslavia. During the interwar period, the fascist Italian government undertook a campaign of Italianisation in the areas it annexed, which suppressed Slavic language, schools, political parties, and cultural institutions. Between 1922 and the beginning of World War II, the affected people were also the German-speaking and Ladin-speaking populations of Trentino-Alto Adige, and the French- and Arpitan-speaking regions of the western Alps, such as the Aosta valley.[81]

Mussolini promised to bring Italy back as a great power in Europe, building a "New Roman Empire"[82] and holding power over the Mediterranean Sea. In propaganda, Fascists used the ancient Roman motto "Mare Nostrum" (Latin for "Our Sea") to describe the Mediterranean. For this reason the Fascist regime engaged in interventionist foreign policy. In 1923, the Greek island of Corfu was briefly occupied by Italy, after the assassination of General Tellini in Greek territory. In 1925, Italy forced Albania to become a de facto protectorate. In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia and founded Italian East Africa, resulting in an international alienation and leading to Italy's withdrawal from the League of Nations; Italy allied with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan and strongly supported Francisco Franco in the Spanish civil war. In 1939, Italy formally annexed Albania. Italy entered World War II on 10 June 1940. The Italians initially advanced in British Somaliland, Egypt, the Balkans (establishing the Governorate of Dalmatia and Montenegro, the Province of Ljubljana, and the puppet states Independent State of Croatia and Hellenic State), and eastern fronts. They were, however, subsequently defeated on the Eastern Front as well as in the East African campaign and the North African campaign, losing as a result their territories in Africa and in the Balkans.

During World War II, Italian war crimes included extrajudicial killings and ethnic cleansing[83] by deportation of about 25,000 people, mainly Jews, Croats, and Slovenians, to the Italian concentration camps, such as Rab, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari, and elsewhere. Yugoslav Partisans perpetrated their own crimes against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) during and after the war, including the foibe massacres. In Italy and Yugoslavia, unlike in Germany, few war crimes were prosecuted.[84][85][86][87]

Italian partisans in Milan during the Italian Civil War, April 1945

Italian partisans in Milan during the Italian Civil War, April 1945An Allied invasion of Sicily began in July 1943, leading to the collapse of the Fascist regime and the fall of Mussolini on 25 July. Mussolini was deposed and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III in co-operation with the majority of the members of the Grand Council of Fascism, which passed a motion of no confidence. On 8 September, Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile, ending its war with the Allies. Shortly thereafter, the Germans, with the assistance of the Italian fascists, succeeded in taking control of northern and central Italy. The country remained a battlefield for the rest of the war, with the Allies slowly moving up from the south.

In the north, the Germans set up the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a Nazi puppet state with Mussolini installed as leader after he was rescued by German paratroopers. Some Italian troops in the south were organised into the Italian Co-belligerent Army, which fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war, while other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini and his RSI, continued to fight alongside the Germans in the National Republican Army. Also, the post-armistice period saw the rise of a large anti-fascist resistance movement, the Resistenza, which fought a guerrilla war against the Nazi German occupiers and Italian Fascist forces. As result, the country descended into civil war. In late April 1945, with total defeat looming, Mussolini attempted to escape north,[88] but was captured and summarily executed near Lake Como by Italian partisans. His body was then taken to Milan, where it was hung upside down at a service station for public viewing and to provide confirmation of his demise.[89]

Hostilities ended on 29 April 1945, when the German forces in Italy surrendered. Nearly half a million Italians (including civilians) died in the conflict,[90] society was divided and the Italian economy had been all but destroyed; per capita income in 1944 was at its lowest point since the beginning of the 20th century.[91] The aftermath of World War II left Italy also with an anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime for the previous twenty years. These frustrations contributed to a revival of the Italian republican movement.[92]

Republican era Alcide De Gasperi, first republican Prime Minister of Italy and one of the Founding Fathers of the European Union

Alcide De Gasperi, first republican Prime Minister of Italy and one of the Founding Fathers of the European UnionItaly became a republic after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum[93] held on 2 June 1946, a day celebrated since as Festa della Repubblica. This was the first time that Italian women voted at the national level, and the second time overall considering the local elections that were held a few months earlier in some cities.[94][95] Victor Emmanuel III's son, Umberto II, was forced to abdicate and exiled. The Republican Constitution was approved on 1 January 1948. Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Istria, Kvarner, most of the Julian March as well as the Dalmatian city of Zara was annexed by Yugoslavia causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), the others being ethnic Slovenians, ethnic Croatians, and ethnic Istro-Romanians, choosing to maintain Italian citizenship.[96] Later, the Free Territory of Trieste was divided between the two states. Italy also lost all of its colonial possessions, formally ending the Italian Empire. In 1950, Italian Somaliland was made a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration until 1 July 1960. The Italian border that applies today has existed since 1975, when Trieste was formally re-annexed to Italy.

Fears of a possible Communist takeover proved crucial for the first universal suffrage electoral outcome on 18 April 1948, when the Christian Democrats, under the leadership of Alcide De Gasperi, obtained a landslide victory.[97][98] Consequently, in 1949 Italy became a member of NATO. The Marshall Plan helped to revive the Italian economy which, until the late 1960s, enjoyed a period of sustained economic growth commonly called the "Economic Miracle". In the 1950's, Italy became one of the six founding countries of the European Communities, following the 1952 establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community, and subsequent 1958 creations of the European Economic Community and European Atomic Energy Community. In 1993, the former two of these were incorporated into the European Union.

The signing ceremony of the Treaty of Rome on 25 March 1957, creating the European Economic Community, forerunner of the present-day European Union

The signing ceremony of the Treaty of Rome on 25 March 1957, creating the European Economic Community, forerunner of the present-day European UnionFrom the late 1960s until the early 1980s, the country experienced the Years of Lead, a period characterised by economic crisis, especially after the 1973 oil crisis, widespread social conflicts and terrorist massacres carried out by opposing extremist groups, with the alleged involvement of US and Soviet intelligence.[99][100][101] The Years of Lead culminated in the assassination of the Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro in 1978 and the Bologna railway station massacre in 1980, where 85 people died.

In the 1980s, for the first time since 1945, two governments were led by non-Christian-Democrat premiers: one republican, Giovanni Spadolini, and one socialist, Bettino Craxi; the Christian Democrats remained, however, the main government party. During Craxi's government, the economy recovered and Italy became the world's fifth-largest industrial nation after it gained the entry into the Group of Seven in the 1970s. However, as a result of his spending policies, the Italian national debt skyrocketed during the Craxi era, soon passing 100% of the country's GDP.

Funerals of the victims of the Bologna bombing of 2 August 1980, the deadliest attack ever perpetrated in Italy during the Years of Lead

Funerals of the victims of the Bologna bombing of 2 August 1980, the deadliest attack ever perpetrated in Italy during the Years of LeadItaly faced several terror attacks between 1992 and 1993 perpetrated by the Sicilian Mafia as a consequence of several life sentences pronounced during the "Maxi Trial", and of the new anti-mafia measures launched by the government. In 1992, two major dynamite attacks killed the judges Giovanni Falcone (23 May in the Capaci bombing) and Paolo Borsellino (19 July in the Via D'Amelio bombing).[102] One year later (May–July 1993), tourist spots were attacked, such as the Via dei Georgofili in Florence, Via Palestro in Milan, and the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano and Via San Teodoro in Rome, leaving 10 dead and 93 injured and causing severe damage to cultural heritage such as the Uffizi Gallery. The Catholic Church openly condemned the Mafia, and two churches were bombed and an anti-Mafia priest shot dead in Rome.[103][104][105]

Asylum seekers arrive in Sicily, 2015, during the European migrant crisis.

Asylum seekers arrive in Sicily, 2015, during the European migrant crisis.Also in the early 1990s, Italy faced significant challenges, as voters – disenchanted with political paralysis, massive public debt and the extensive corruption system (known as Tangentopoli) uncovered by the Clean Hands (Mani Pulite) investigation – demanded radical reforms. The scandals involved all major parties, but especially those in the government coalition: the Christian Democrats, who ruled for almost 50 years, underwent a severe crisis and eventually disbanded, splitting up into several factions.[106] The Communists reorganised as a social-democratic force. During the 1990s and the 2000s, centre-right (dominated by media magnate Silvio Berlusconi) and centre-left coalitions (led by university professor Romano Prodi) alternately governed the country.

Amidst the Great Recession, Berlusconi resigned in 2011, and his conservative government was replaced by the technocratic cabinet of Mario Monti.[107] Following the 2013 general election, the Vice-Secretary of the Democratic Party Enrico Letta formed a new government at the head of a right-left Grand coalition. In 2014, challenged by the new Secretary of the PD Matteo Renzi, Letta resigned and was replaced by Renzi. The new government started constitutional reforms such as the abolition of the Senate and a new electoral law. On 4 December the constitutional reform was rejected in a referendum and Renzi resigned; the Foreign Affairs Minister Paolo Gentiloni was appointed new Prime Minister.[108]

Italian government task force to face the COVID-19 emergency

Italian government task force to face the COVID-19 emergencyIn the European migrant crisis of the 2010s, Italy was the entry point and leading destination for most asylum seekers entering the EU. From 2013 to 2018, the country took in over 700,000 migrants and refugees,[109] mainly from sub-Saharan Africa,[110] which caused strain on the public purse and a surge in the support for far-right or euro-sceptic political parties.[111][112] The 2018 general election was characterised by a strong showing of the Five Star Movement and the League and the university professor Giuseppe Conte became the Prime Minister at the head of a populist coalition between these two parties.[113] However, after only fourteen months the League withdrew its support to Conte, who formed a new unprecedented government coalition between the Five Star Movement and the centre-left.[114][115]

In 2020, Italy was severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.[116] From March to May, Conte's government imposed a national lockdown as a measure to limit the spread of the disease,[117][118] while further restrictions were introduced during the following winter.[119] The measures, despite being widely approved by the public opinion,[120] were also described as the largest suppression of constitutional rights in the history of the republic.[121][122] With more than 155,000 confirmed victims, Italy was one of the countries with the highest total number of deaths in the worldwide coronavirus pandemic.[123] The pandemic caused also a severe economic disruption, in which Italy resulted as one of the most affected countries.[124]

In February 2021, after a government crisis within his majority, Conte was forced to resign and Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank, formed a national unity government supported by almost all the main parties,[125] pledging to oversee implementation of economic stimulus to face the crisis caused by the pandemic.[126] On 22 October 2022, Giorgia Meloni was sworn in as Italy's first female prime minister. Her Brothers of Italy party formed a right-wing government with the far-right League and Berlusconi's Forza Italia.[127]

^ "Sassi di Matera". AmusingPlanet. ^ Society, National Geographic. "Erano padani i primi abitanti d'Italia". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019. ^ Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers 2001, ch. 2. ISBN 0-306-46463-2. ^ 42.7–41.5 ka (1σ CI). Douka, Katerina; et al. (2012). "A new chronostratigraphic framework for the Upper Palaeolithic of Riparo Mochi (Italy)". Journal of Human Evolution. 62 (2): 286–299. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.009. PMID 22189428. ^ "Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria". IIPP. 29 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. ^ "Rock Drawings in Valcamonica". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 29 June 2010. ^ Bonani, Georges; Ivy, Susan D.; et al. (1994). "AMS 14

C

Age Determination of Tissue, Bone and Grass Samples from the Ötzal Ice Man" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 36 (2): 247–250. doi:10.1017/s0033822200040534. Retrieved 4 February 2016. ^ Raclot, Thierry; Oudart, Hugues (January 2000). "CORPS GRAS ET OBESITE Acides gras alimentaires et obésité: aspects qualitatifs et quantitatifs". Oléagineux, Corps gras, Lipides. 7 (1): 77–85. doi:10.1051/ocl.2000.0077. ISSN 1258-8210. ^ The Mycenaeans Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine and Italy: the archaeological and archaeometric ceramic evidence, University of Glasgow, Department of Archaeology ^ Gert Jan van Wijngaarden, Use and Appreciation of Mycenaean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (1600–1200 B.C.): The Significance of Context, Amsterdam Archaeological Studies, Amsterdam University Press, 2001 ^ Bryan Feuer, Mycenaean civilization: an annotated bibliography through 2002, McFarland & Company; Rev Sub edition (2 March 2004) ^ Emilio Peruzzi, Mycenaeans in early Latium, (Incunabula Graeca 75), Edizioni dell'Ateneo & Bizzarri, Roma, 1980 ^ "II 1987: Uomini e vicende di Magna Grecia". www.bpp.it. Retrieved 31 January 2021. ^ Morcillo, Marta García. "The Glory of Italy and Rome's Universal Destiny in Strabo's Geographika, in: A. Fear – P. Liddel (eds), Historiae Mundi. Studies in Universal History. Duckworth: London 2010: 87-101". Historiae Mundi: Studies in Universal History. Retrieved 20 November 2021. ^ Keaveney, Arthur (January 1987). Arthur Keaveney: Rome and the Unification of Italy. ISBN 9780709931218. Retrieved 20 November 2021. ^ Billanovich, Giuseppe (2008). Libreria Universitaria Hoepli, Lezioni di filologia, Giuseppe Billanovich e Roberto Pesce: Corpus Iuris Civilis, Italia non erat provincia, sed domina provinciarum, Feltrinelli, p.363 (in Italian). ISBN 9788896543092. Retrieved 20 November 2021. ^ Fear, Andrew (25 March 2010). Historiae Mundi: Studies in Universal History. ISBN 978-1-4725-1980-1. ^ Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 115–138. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959. ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (2006). "East–West Orientation of Historical Empires" (PDF). Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. doi:10.5195/JWSR.2006.369. ISSN 1076-156X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016. ^ Richard, Carl J. (2010). Why we're all Romans: the Roman contribution to the western world (1st pbk. ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. xi–xv. ISBN 978-0-7425-6779-5. ^ Sarris, Peter (2011). Empires of faith: the fall of Rome to the rise of Islam, 500–700 (1st. pub. ed.). Oxford: Oxford UP. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-926126-0. ^ "History of Italy". Britannica. ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA. Retrieved 29 September 2022. ^ "Carolingian and post-Carolingian Italy, 774–962". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 October 2022. ^ Nolan, Cathal J. (2006). The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization (1. publ. ed.). Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-313-33045-2. ^ "Marco Polo – Exploration". History.com. Retrieved 9 January 2017. ^ Jones, Philip (1997). The Italian city-state: from Commune to Signoria. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 55–77. ISBN 978-0-19-822585-0. ^ Niall, Ferguson (2008). The Ascent of Money: The Financial History of the World. Penguin. ^ a b Lane, Frederic C. (1991). Venice, a maritime republic (4. print. ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8018-1460-0. ^ G. Benvenuti – Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia – Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini, Le repubbliche del mare, Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma. Peris, Persi (1982). Conoscere l'Italia. Istituto Geografico De Agostini. p. 74. ^ "Repubbliche Marinare". Treccani.it (in Italian). Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ^ "Repubbliche marinare". thes.bncf.firenze.sbn.it (in Italian). National Central Library (Florence). ^ Zorzi, Alvise (1983). Venice: The Golden Age, 697 – 1797. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 255. ISBN 0-89659-406-8. Retrieved 16 September 2017. ^ Cite error: The named reference auto was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Ali, Ahmed Essa with Othman (2010). Studies in Islamic civilization: the Muslim contribution to the Renaissance. Herndon, VA: International Institute of Islamic Thought. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-56564-350-5. ^ Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, "The Biggest Epidemics of History" (La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire), in L'Histoire n° 310, June 2006, pp. 45–46 ^ "Plague". Brown University. Archived 31 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine ^ a b Strathern, Paul The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance (2003) ^ Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo: Mysteries of Medici Chapel, SLOVO, Moscow, 2006 Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 5-85050-825-2 ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Renaissance, 2008, O.Ed. ^ Har, Michael H. History of Libraries in the Western World, Scarecrow Press Incorporate, 1999, ISBN 0-8108-3724-2 ^ Norwich, John Julius, A Short History of Byzantium, 1997, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45088-2 ^ Leonardo Bruni; James Hankins (9 October 2010). History of the Florentine People. Vol. 1. Boston: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia "John & Sebastian Cabot"". newadvent. 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2008. ^ Eric Martone (2016). Italian Americans: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. p. 504. ISBN 9781610699952. ^ Greene, George Washington (1837). The Life and Voyages of Verrazzano. Cambridge University: Folsom, Wells, and Thurston. p. 13. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via Google Books. ^ Napoleon Bonaparte, "The Economy of the Empire in Italy: Instructions from Napoleon to Eugène, Viceroy of Italy," Exploring the European Past: Texts & Images, Second Edition, ed. Timothy E. Gregory (Mason: Thomson, 2007), 65–66. ^ Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. p. 156. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2. ^ The tri-coloured standard.Getting to Know Italy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (retrieved 5 October 2008) Archived 23 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine ^ Article 1 of the law n. 671 of 31 December 1996 ("National celebration of the bicentenary of the first national flag") ^ Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna Storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 662. ^ Tarozzi, Fiorenza; Vecchio, Giorgio (1999). Gli italiani e il tricolore (in Italian). Il Mulino. pp. 67–68. ISBN 88-15-07163-6. ^ a b "Scholar and Patriot". Manchester University Press – via Google Books. ^ "Giuseppe Garibaldi (Italian revolutionary)". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014. ^ Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. p. 18. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2. ^ "Fratelli d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 October 2021. ^ Denis Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History, (University of Michigan Press, 1997) p. 15. A literary echo may be found in the character of Giorgio Viola in Joseph Conrad's Nostromo. ^ Enrico Dal Lago, "Lincoln, Cavour, and National Unification: American Republicanism and Italian Liberal Nationalism in Comparative Perspective." The Journal of the Civil War Era 3#1 (2013): 85–113. ^ William L. Langer, ed., An Encyclopedia of World Cup History. 4th ed. 1968. pp 704–7. ^ ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). 28 August 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2021. ^ Mack Smith, Denis (1997). Modern Italy; A Political History. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10895-6 ^ "Everything you need to know about March 17th, Italy's Unity Day". 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017. ^ (Bosworth (2005), p. 49.) ^ "Il 1861 e le quattro Guerre per l'Indipendenza (1848–1918)" (in Italian). 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2021. ^ "La Grande Guerra nei manifesti italiani dell'epoca" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2021. ^ Genovesi, Piergiovanni (11 June 2009). Il Manuale di Storia in Italia, di Piergiovanni Genovesi (in Italian). ISBN 9788856818680. Retrieved 12 March 2021. ^ Burgwyn, H. James: Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997. p. 4. ISBN 0-275-94877-3 ^ Schindler, John R.: Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. p. 303. ISBN 0-275-97204-6 ^ Mack Smith, Denis: Mussolini. Knopf, 1982. p. 31. ISBN 0-394-50694-4 ^ Mortara, G (1925). La Salute pubblica in Italia durante e dopo la Guerra. New Haven: Yale University Press. ^ G.Sabbatucci, La vittoria mutilata, in AA.VV., Miti e storia dell'Italia unita, Il Mulino, Bologna 1999, pp.101–106 ^ Lyttelton, Adrian (2008). The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy, 1919–1929. New York: Routledge. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-415-55394-0. ^ "March on Rome | Italian history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2017. ^ Aristotle A. Kallis. Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945. London, England, UK; New York City, USA: Routledge, 2000, pp. 41. ^ Terence Ball, Richard Bellamy. The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Political Thought. Pp. 133 ^ Jozo Tomasevich. War and Revolution in Yugoslavia 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press, 2001. P. 131. ^ Larry Wolff. Venice And the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press, P. 355. ^ Aristotle A. Kallis. Fascist Ideology: Expansionism in Italy and Germany 1922–1945. London, England; UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2000. P. 118. ^ Mussolini Unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986, 1999. P. 38. ^ a b Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. P. 88. ^ "I nomi dei comuni valdostani durante il fascismo" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 February 2022. ^ Stephen J. Lee (2008). European Dictatorships, 1918–1945. Routledge. pp. 157–58. ISBN 978-0-415-45484-1. ^ James H. Burgwyn (2004). General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942 Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16) ^ Italy's bloody secret (archived by WebCite), written by Rory Carroll, Education, The Guardian, June 2001 ^ Effie Pedaliu (2004) JSTOR 4141408? Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 ^ Oliva, Gianni (2006) «Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43 Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Mondadori, ISBN 88-04-55129-1 ^ Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo, L'Ancora del Mediterraneo. ISBN 978-88-8325-135-1 ^ Viganò, Marino (2001), "Un'analisi accurata della presunta fuga in Svizzera", Nuova Storia Contemporanea (in Italian), 3 ^ "1945: Italian partisans kill Mussolini". BBC News. 28 April 1945. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011. ^ "Italy – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2010. ^ Adrian Lyttelton (editor), "Liberal and fascist Italy, 1900–1945", Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 13 ^ "Italia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. VI, Treccani, 1970, p. 456 ^ Damage Foreshadows A-Bomb Test, 1946/06/06 (1946). Universal Newsreel. 1946. Retrieved 22 February 2012. ^ "Italia 1946: le donne al voto, dossier a cura di Mariachiara Fugazza e Silvia Cassamagnaghi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011. ^ "La prima volta in cui le donne votarono in Italia, 75 anni fa". Il Post (in Italian). 10 March 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021. ^ Tobagi, Benedetta. "La Repubblica italiana | Treccani, il portale del sapere". Treccani.it. Retrieved 28 January 2015. ^ Lawrence S. Kaplan; Morris Honick (2007). NATO 1948: The Birth of the Transatlantic Alliance. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-0-7425-3917-4. ^ Robert Ventresca (2004). From Fascism to Democracy: Culture and Politics in the Italian Election of 1948. University of Toronto Press. pp. 236–37. ^ "Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul terrorismo in Italia e sulle cause della mancata individuazione dei responsabili delle stragi (Parliamentary investigative commission on terrorism in Italy and the failure to identify the perpetrators)" (PDF) (in Italian). 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006. ^ (in English, Italian, French, and German) "Secret Warfare: Operation Gladio and NATO's Stay-Behind Armies". Swiss Federal Institute of Technology / International Relation and Security Network. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006. ^ "Clarion: Philip Willan, Guardian, 24 June 2000, p. 19". Cambridgeclarion.org. 24 June 2000. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2010. ^ "New Arrests for Via D'Amelio Bomb Attack". corriere.it. 8 March 2012. ^ John Dickie (2007). Cosa Nostra. A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 416. ISBN 978-0340935262. ^ "Sentenza del processo di 1º grado a Francesco Tagliavia per le stragi del 1993" (PDF). ^ "Audizione del procuratore Sergio Lari dinanzi alla Commissione Parlamentare Antimafia – XVI LEGISLATURA (PDF)" (PDF). ^ The so-called "Second Republic" was born by forceps: not with a revolt of Algiers, but formally under the same Constitution, with the mere replacement of one ruling class by another: Buonomo, Giampiero (2015). "Tovaglie pulite". Mondoperaio Edizione Online. ^ Hooper, John (16 November 2011). "Mario Monti appoints technocrats to steer Italy out of economic crisis". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 March 2020. ^ "New Italian PM Paolo Gentiloni sworn in". BBC News. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2020. ^ "What will Italy's new government mean for migrants?". The Local Italy. 21 May 2018. ^ "African migrants fear for future as Italy struggles with surge in arrivals". Reuters. 18 July 2017. ^ "Italy starts to show the strains of migrant influx". The Local. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017. ^ "Italy's far right jolts back from dead". Politico. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017. ^ "Opinion – The Populists Take Rome". The New York Times. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2018. ^ "Italy's Conte forms coalition of bitter rivals, booting far-right from power". France 24. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019. ^ "New Italian government formed, allying M5S and the center-left | DW | 4 September 2019". Deutsche Welle. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019. ^ Nuovo coronavirus, Minsitero della Salute ^ "Coronavirus: Italy extends emergency measures nationwide". BBC News. 10 March 2020. ^ Beaumont, Peter; Sample, Ian (10 March 2020). "From confidence to quarantine: how coronavirus swept Italy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 March 2020. ^ "Coronavirus, Conte firma il nuovo Dpcm: in semi-lockdown per un mese. Stop a bar e ristoranti alle 18 ma aperti la domenica". la Repubblica (in Italian). 25 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020. ^ De Feo, Gianluca (20 March 2020). "Sondaggio Demos: gradimento per Conte alle stelle". YouTrend (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2020. ^ "Blog | Coronavirus, la sospensione delle libertà costituzionali è realtà. Ma per me ce la stiamo cavando bene". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020. ^ "Un uomo solo è al comando dell'Italia, e nessuno ha niente da ridire". Linkiesta (in Italian). 24 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020. ^ Ellyatt, Holly (19 March 2020). "Italy's lockdown will be extended, prime minister says as death toll spikes and hospitals struggle". CNBC. Retrieved 19 March 2020. ^ L'Italia pagherà il conto più salato della crisi post-epidemia, AGI ^ Mario Draghi sworn in as Italy's new prime minister, BBC ^ "Mario Draghi's new government to be sworn in on Saturday". the Guardian. 12 February 2021. ^ "Who is Giorgia Meloni? The rise to power of Italy's new far-right PM". BBC News. 21 October 2022.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- Stay safe

Mounted Carabinieri in Milan.

Mounted Carabinieri in Milan.For emergencies, call 113 (Polizia di Stato - State Police), 112 (Carabinieri - Gendarmerie), 117 (Guardia di Finanza - Financial police force), 115 (Fire Department), 118 (Medical Rescue), 1515 (State Forestry Department), 1530 (Coast Guard), 1528 (Traffic reports).

Italy is a safe country to travel in like most developed countries. There are few incidents of terrorism/serious violence and these episodes have been almost exclusively motivated by internal politics. Almost every major incident is attributed to organised crime or anarchist movements and rarely, if ever, directed at travellers or foreigners.

CrimeViolent crime rates in Italy are low compared to most European countries. If you're reasonably careful and use common sense you won't encounter personal safety risks even in the less affluent neighborhoods of large cities. However, petty crime can be a problem for unwary travellers. Pickpockets often work in pairs or teams, occasionally in conjunction with street vendors; take the usual precautions against pickpockets. Instances of rape and robbery are increasing slightly.

...Read moreStay safeRead less Mounted Carabinieri in Milan.

Mounted Carabinieri in Milan.For emergencies, call 113 (Polizia di Stato - State Police), 112 (Carabinieri - Gendarmerie), 117 (Guardia di Finanza - Financial police force), 115 (Fire Department), 118 (Medical Rescue), 1515 (State Forestry Department), 1530 (Coast Guard), 1528 (Traffic reports).

Italy is a safe country to travel in like most developed countries. There are few incidents of terrorism/serious violence and these episodes have been almost exclusively motivated by internal politics. Almost every major incident is attributed to organised crime or anarchist movements and rarely, if ever, directed at travellers or foreigners.

CrimeViolent crime rates in Italy are low compared to most European countries. If you're reasonably careful and use common sense you won't encounter personal safety risks even in the less affluent neighborhoods of large cities. However, petty crime can be a problem for unwary travellers. Pickpockets often work in pairs or teams, occasionally in conjunction with street vendors; take the usual precautions against pickpockets. Instances of rape and robbery are increasing slightly.

You should exercise the usual caution when going out at night alone, although it remains reasonably safe even for single women to walk alone at night. Italians will often offer to accompany female friends back home for safety, even though crime statistics show that sexual violence against women is rare compared to most other Western countries. In a survey by United Nations, 14% of Italian women had experienced attempted rape and 2.3% had experienced rape in their lifetimes.

The mafia, camorra, and other crime syndicates generally operate in southern Italy and not the whole country, and although infamous are usually not involved in petty crime.

Prostitution is rife in the night streets around cities. Prostitution in Italy is not exactly illegal, though authorities are taking a firmer stance against it than before. Brothels are illegal, though, and pimping is a serious offence, considered by the law similar to slavery. In some areas, it is an offence even to stop your car in front of a prostitute although the rows of prostitutes at the side of many roads, particularly in the suburbs, suggest that the law is not enforced. In general, being the client of a prostitute falls in an area of questionable legality and is inadvisable. Being the client of a prostitute under 18 is a criminal offence. It is estimated that a high percentage of prostitutes working in Italy are victims of human trafficking and modern-day slavery.

There are four types of police forces a tourist might encounter in Italy. The Polizia di Stato (State Police) is the national police force and stationed mostly in the larger towns and cities, and by train stations; they wear blue shirts and grey pants and drive light-blue-painted cars with "POLIZIA" written on the side. The Carabinieri are the national gendarmerie, and are found in the smaller communities, as well as in the cities; they wear very dark blue uniforms with fiery red vertical stripes on their trousers and drive similarly-coloured cars. There is no real distinction between the roles of these two major police forces: both can intervene, investigate, and prosecute in the same way.

The Guardia di Finanza is a police force charged with border controls and fiscal matters; although not a patrolling police force, they sometime aid the other forces in territory control. They dress fully in light grey and drive blue or gray cars with yellow markings. All these police forces are generally professional and trustworthy, corruption being virtually unheard of. Finally, municipalities have local police, with names such as "Polizia municipale" or "Polizia locale" (previously, they were labelled "Vigili urbani"). Their style of dressing varies among the cities, but they will always wear some type of blue uniform with white piping and details, and drive similarly marked cars, which should be easy to spot. These local police forces are not trained for major policing interventions, as in the past they have mostly been treated as traffic police, employed for minor tasks; in the event of major crimes, the Polizia or Carabinieri will be summoned instead.

After leaving a restaurant or other commercial facility, it is possible, though unlikely, that you will be asked to show your bill and your documents to Guardia di Finanza agents. This is perfectly legitimate (they are checking to see if the facility has printed a proper receipt and will thus pay taxes on what was sold).