Fort Ross, California

Fort Ross is a former Russian establishment on the west coast of North America in what is now Sonoma County, California. It was the hub of the southernmost Russian settlements in North America from 1812 to 1841. Notably, it was the first multi-ethnic community in northern California, with a combination of Native Californians, Native Alaskans, Russians, Finns, and Swedes. It has been the subject of archaeological investigation and is a California Historical Landmark, a National Historic Landmark, and on the National Register of Historic Places. It is part of California's Fort Ross State Historic Park.

Beginning with Columbus in 1492, the Spanish presence in the Western Hemisphere traveled west across the Atlantic Ocean, then around or across the Americas to reach the Pacific Ocean. The Russian expansion, however, moved east across Siberia and the northern Pacific. In the early nineteenth century, Spanish and Russian expansion met along the coast of Spanish Alta California, with Russia pushing south and Spain pushing north. By that time, British and American fur trade companies had also established a coastal presence, in the Pacific Northwest, and Mexico was soon to gain independence. Mexico ceded Alta California to the United States of America following the Mexican–American War (1848). The history of the Russian Fort Ross settlement began during Spanish rule and ended under Mexican rule.

Earliest peopleThe earliest people known to have lived at the site were there during the Upper Archaic period (1000 B.C. - A.D. 500) and the Lower Emergent period (A.D. 1000 - 1500), but the main occupation began at A.D. 1500 and continued through 1812. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence suggest that the Native Californians lived in large and mostly permanent villages. In summer months, they had "special purpose camps" they would go to in order to get certain resources. This area was one of such camps, used for its access to tidal and marine resources.

Ethnographic evidence suggests that the area where Fort Ross would be located was a large part of Kashaya Pomo territory. Their name for the site was "Metini". Their exact arrival date is unknown, but according to linguistic and archaeological data, they moved to Metini sometime between 1,000 and 500 B.C. Archaeological data shows that the Kashaya Pomo increased their subsistence activities upon arrival at this site and gained greater diversity in their tool kits.[1]

Russian-American CompanyRussian personnel from the Alaskan colonies initially arrived in California aboard American ships. In 1803, American ship captains already involved in the sea otter maritime fur trade in California proposed several joint venture hunting expeditions to Alexander Andreyevich Baranov, on half shares using Russian supervisors and native Alaskan hunters to hunt fur seals and otters along the Alta and Baja Californian coast. Subsequent reports by the Russian hunting parties of uncolonized stretches of coast encouraged Baranov, the Chief Administrator of the Russian-American Company (RAC), to consider a settlement in California north of the limit of Spanish occupation in San Francisco. In 1806 the Russian Ambassador to Japan, and RAC director Nikolay Rezanov, undertook an exploratory trade mission to California to establish a formal means of procuring food supplies in exchange for Russian goods in San Francisco. While guests of the Spanish, Rezanov's captain, Lt. Khvostov, explored and charted the coast north of San Francisco Bay and found it completely unoccupied by other European powers. Upon his return to Novoarkhangelsk (New Archangel), Rezanov recommended to Baranov, and the Emperor Alexander, that a settlement be established in California.[2]

This settlement [Ross] has been organized through the initiative of the Company. Its purpose is to establish a [Russian] settlement there or in some other place not occupied by Europeans, and to introduce agriculture there by planting hemp, flax and all manner of garden produce; they also wish to introduce livestock breeding in the outlying areas, both horses and cattle, hoping that the favorable climate, which is almost identical to the rest of California, and the friendly reception on the part of the indigenous people, will assist in its success.

Fort Ross was established by Commerce Counselor Ivan Kuskov of the Russian-American Company.[3][4]: 83–84 In 1808 Baranov sent two ships, the Kad'yak and the Sv. Nikolai, on an expedition south to establish settlements for the RAC with instructions to bury "secret signs" (possession plaques). Kuskov, on the Kad'yak, was instructed to bury the plaques, with an appropriate possession ceremony, at Trinidad, Bodega Bay, and on the shore north of San Francisco, indicating Russian claims to the land. After sailing into Bodega Bay in 1809 on the Kad'yak and returning to Novoarkhangelsk with beaver skins and 1,160 otter pelts, Baranov ordered Kuskov to return and establish an agricultural settlement in the area. After a failed attempt in 1811, Kuskov sailed the brig Chirikov back to Bodega Bay in March 1812, naming it the Gulf of Rumyantsev or Rumyantsev Bay (залив Румянцева, Zaliv Rumyantseva) in honor of the Russian Minister of Commerce Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantzev.[5] [6] He also named the Russian River the Slavic River (Славянка, Slavyanka). On his return, Kuskov found American otter hunting ships and otter now scarce in Bodega Bay. After exploring the area they ended up selecting a place 15 miles (24 km) north that the native Kashaya Pomo people called Mad shui nui or Metini. Metini, the seasonal home of the Kashaya Pomo, had a modest anchorage and abundant natural resources and would become the Russian settlement of Fortress Ross.

Fort Ross was established as an agricultural base from which the northern settlements could be supplied with food, while also continuing trade with Alta California.[2] Yet during its initial ten years of operations the post "provided the company with nothing but heavy expenses for its maintenance."[7] Fort Ross itself was the hub of a number of smaller Russian settlements comprising what was called "Fortress Ross" on official documents and charts produced by the Company itself.[8] Colony Ross referred to the entire area where Russians had settled.[8] These settlements constituted the southernmost Russian colony in North America and were spread over an area stretching from Point Arena to Tomales Bay.[9] The colony included a port at Bodega Bay called Port Rumyantsev (порт Румянцев), a sealing station on the Farallon Islands 18 miles (29 km) out to sea from San Francisco, and by 1830 three small farming communities called "ranchos" (Ранчо): Chernykh (Ранчо Егора Черных, Rancho Egora Chernykh) near present-day Graton, Khlebnikov (Ранчо Василия Хлебникова, Rancho Vasiliya Khlebnikova) a mile north of the present day town of Bodega in the Salmon Creek valley, and Kostromitinov (Ранчо Петра Костромитинова, Rancho Petra Kostromitinova)[9] on the Russian River.

A view of Fort Ross in 1828 by A. B. Duhaut-Cilly. From the archives of the Fort Ross Historical SocietyLocal enterprise

A view of Fort Ross in 1828 by A. B. Duhaut-Cilly. From the archives of the Fort Ross Historical SocietyLocal enterprise

In addition to farming and manufacturing, the Company carried on its fur-trading business at Fort Ross, but by 1817, after 20 years of intense hunting by Spanish, American and British ships—followed by Russian efforts—sea otters had been practically eliminated from the area.[10]

Settlement Ross, 1841, by Ilya Gavrilovich Voznesensky

Settlement Ross, 1841, by Ilya Gavrilovich VoznesenskyFort Ross was the site of California's first windmills and shipbuilding. Russian scientists associated with the colony were among the first to record California's cultural and natural history.[11] The Russian managers introduced many European innovations such as glass windows, stoves, and all-wood housing into Alta California. Together with the surrounding settlement, Fort Ross was home to Russian subjects (which during the 19th and early 20th century included Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Belarusians, Finns, Baltic Germans, Estonians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Georgians, Circassians, Tatars, and numerous other nationalities and ethnic groups of the Russian Empire[12]), as well as North Pacific Natives, Aleuts, Kashaya (Pomo), and Alaskan Creoles. The native populations of the Sonoma and Napa County regions were affected by smallpox, measles and other infectious diseases that were common across Asia, Europe, and Africa. One instance can be traced to the settlement of Fort Ross.[13] However, the first vaccination in California history was carried out by the crew of the Kutuzov, a Russian-American Company vessel arriving from Callao, Peru which brought vaccine to Monterey in August, 1821. The Kutuzov's surgeon vaccinated 54 persons. Another instance of disease prevention was when a visiting Hudson's Bay Company hunting party was refused entry to the Colony in 1833, when it was feared that a malaria epidemic which had devastated the Central Valley was carried by its members. In 1837 a very deadly epidemic of smallpox that came from this settlement via New Archangel wiped out most native people in the Sonoma and Napa County regions.[13]

Mexican responseBetween 1824 and 1836 the Mexicans found during every exploratory effort north of present-day San Rafael and west of Sonoma increasing evidence of Russian presence. They discovered at least three Russian farms that had been established inland from Fort Ross. Governor José Figueroa wanted to counter the Russians' gradual encroachment in Northern California.[14] In 1834, he granted Rancho Petaluma to Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. In 1835 he appointed Vallejo as Comandante of the Fourth Military District and Director of Colonization of the Northern Frontier, the highest military command in Northern California, and encouraged him to build the Presidio of Sonoma. To extend the settlements in the direction of Fort Ross, Vallejo granted his brother-in-law, Captain John B. R. Cooper, who had married his sister Encarnacion, Rancho El Molino (about 17,892-acre (72.41 km2)). The grant was confirmed by Governor Nicolás Gutiérrez in 1836.[15]

Upon his arrival in Alta California in 1839, John Sutter was attracted to the land near the Sacramento River. To obtain the land and permission to settle in the territory, he went to the capital at Monterey and requested a grant from Governor Juan Bautista Alvarado. Alvarado saw Sutter's plan of establishing a colony in the Central Valley as useful in "buttressing the frontier which he was trying to maintain against Indians, Russians, Americans and British."[16] Sutter persuaded Governor Alvarado to grant him 48,400 acres (19,600 ha) of land for the sake of curtailing American encroachment on the Mexican territory of California. Sutter was given the right to "represent in the Establishment of New Helvetia all the laws of the country, to function as political authority and dispenser of justice, in order to prevent the robberies committed by adventurers from the United States, to stop the invasion of savage Indians, and the hunting and trading by companies from the Columbia (river)." He named the settlement New Helvetia.[17] In an 1841 inventory for John Sutter describes the settlement surrounding the fort: "twenty-four planked dwellings with glazed windows, a floor and a ceiling; each had a garden. There were eight sheds, eight bathhouses and ten kitchens."

Decline of Fort RossBy 1839, the settlement's agricultural importance had decreased considerably, the local population of fur-bearing marine mammals had been long depleted by international over-hunting, and the recently secularized California missions no longer supplemented the agricultural needs of the Alaskan colonies. Following the formal trade agreement in 1838 between the Russian-American Company in New Archangel and Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver and Fort Langley for their agricultural needs, the settlement at Fort Ross was no longer needed to supply the Alaskan colonies with food. The Russian-American Company consequently offered the settlement to various potential purchasers, and in 1841 it was sold to John Sutter, a Mexican citizen of Swiss origin, soon to be renowned for the discovery of gold at his lumber mill in the Sacramento valley. Although the settlement was sold for $30,000 to Sutter, some Russian historians assert the sum was never paid; therefore legal title of the settlement was never transferred to Sutter and the area still belongs to the Russian people.[18] A recent Sutter biography[19] however, asserts that Sutter's agent, Peter Burnett, paid the Russian-American Company agent William M. Steuart $19,788 in "notes and gold" on April 13, 1849, thereby settling the outstanding debt for Fort Ross and Bodega.

20th centuryPossession of Fort Ross passed from Sutter through successive private hands and finally to George W. Call. In 1903, the stockade and about 3 acres (12,000 m2) of land were purchased from the Call family by the California Historical Landmarks Commission. Three years later it was turned over to the State of California for preservation and restoration as a state historic monument. Since then, the state has acquired more of the surrounding land for preservation purposes. California Department of Parks and Recreation as well as many volunteers put extensive efforts into restoration and reconstruction work in the Fort.

Southwest blockhouse, with the well in the foreground

Southwest blockhouse, with the well in the foreground  Well

WellCA 1 once bisected Fort Ross. It entered from the northeast where the Kuskov House once stood, and exited through the main gate to the southwest. The road was eventually diverted, and the parts of the fort that had been demolished for the road were rebuilt. The old roadway can still be seen going from the main gate to the northwest; the rest (within the fort and extending northeast) has been removed. CA 1 moved to its current alignment sometime in the mid–late 1970s.

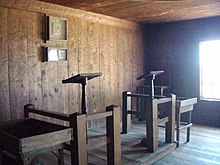

Most of the existing buildings on the site are reconstructions. Cooperative research efforts with Russian archives will help to correct interpretive errors present in structures that date from the Cold-War period. The only original structure remaining is the Rotchev House. Known as the "Commandant's House" from the 1940s through the 1970s, it was the residence of the last manager, Aleksandr Rotchev. Renovated in 1836 from an existing structure, it was titled the "new commandant's house" in the 1841 inventory to differentiate it from the "old commandant's house" (Kuskov House). The Rotchev House, or in original documents, "Administrator's House", is at the center of efforts to "re-interpret" Russia's part in California's colonial history. The Fort Ross Interpretive Association has received several federally funded grants to restore both exterior and interior elements. While its exterior has been partially restored, its interior is currently undergoing restoration to reflect the recent research that shows a more cosmopolitan and refined aspect of colonial life at the Fort.

Interior of Fort Ross Chapel.Fort Ross living history day

Interior of Fort Ross Chapel.Fort Ross living history day Artist's reconstruction of Chapel's appearance in 1841

Artist's reconstruction of Chapel's appearance in 1841The Fort Ross Chapel collapsed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake but much of the original structural woodwork remained and it was re-erected in 1916, but retained the appearance of the American ranch-period modifications when it was used as a stable.[20] Several other restorations ensued, but none incorporated the information in Voznesensky's 1841 water-colour which portray the chapel with copper-clad cupola and tower, and red-metal roof.[20] "The Fort Ross Chapel was found eligible for designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1969, architecturally significant as a rare U.S. example of a log church constructed on a Russian quadrilateral plan. An accidental fire destroyed the chapel on October 5, 1970. This loss of the original workmanship and materials of the chapel led to withdrawal of the Chapel's Landmark designation in 1971. A complete reconstruction of the chapel was undertaken in 1973 and the Fort Ross settlement, as a whole, retains its National Historic Landmark designation."[21] The current chapel was built during the intensive restoration activity that followed, but retains the American ranch period appearance.

A large orchard, including several original trees planted by the Russians, is located inland on Fort Ross Road in Sonoma County.[22]

Fort Ross is now a part of Fort Ross State Historic Park, open to the public.[23] In addition to fishing, hiking, surfing, exploring tide pools, picnicking, whale watching, and bird watching,[24] the Park has become a popular destination for scuba divers, some of whom visit Fort Ross Reef. The wreckage of the SS Pomona[25] lies just offshore Fort Ross State Park.

Add new comment