İstanbul

IstanbulContext of Istanbul

Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul) is the largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, cultural and historic hub. The city straddles the Bosporus Strait, lying in both Europe and Asia, and has a population of over 15 million residents, comprising 19% of the population of Turkey. Istanbul is the most populous European city and the world's 15th largest city.

The city was founded as Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzantion) in the 7th century BCE by Greek settlers from Megara. In 330 CE, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great made it his imperial capital, renaming it first as New Rome (Greek: Νέα Ῥώμη, Ne...Read more

Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul) is the largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, cultural and historic hub. The city straddles the Bosporus Strait, lying in both Europe and Asia, and has a population of over 15 million residents, comprising 19% of the population of Turkey. Istanbul is the most populous European city and the world's 15th largest city.

The city was founded as Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzantion) in the 7th century BCE by Greek settlers from Megara. In 330 CE, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great made it his imperial capital, renaming it first as New Rome (Greek: Νέα Ῥώμη, Nea Rhomē; Latin: Nova Roma) and then as Constantinople (Constantinopolis) after himself. In 1930, the city's name was officially changed to Istanbul, the Turkish rendering of εἰς τὴν Πόλιν (romanized: eis tḕn Pólin; 'to the City'), the appellation Greek speakers used since the 11th century to colloquially refer to the city.

The city served as an imperial capital for almost 1600 years: during the Roman/Byzantine (330–1204), Latin (1204–1261), late Byzantine (1261–1453), and Ottoman (1453–1922) empires. The city grew in size and influence, eventually becoming a beacon of the Silk Road and one of the most important cities in history. The city played a key role in the advancement of Christianity during Roman/Byzantine times, hosting four of the first seven ecumenical councils before its transformation to an Islamic stronghold following the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 CE—especially after becoming the seat of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1517. In 1923, after the Turkish War of Independence, Ankara replaced the city as the capital of the newly formed Republic of Turkey.

Istanbul has surpassed London and Dubai to become the most visited city in the world, with more than 20 million foreign visitors in 2023. The historic centre of Istanbul is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the city hosts the headquarters of numerous Turkish companies, accounting for more than thirty percent of the country's economy.

More about Istanbul

- Native name İstanbul

- Population 14804116

- Area 5343

This large keystone might have belonged to a triumphal arch at the Forum of Constantine (present-day Çemberlitaş).[1]

Read lessThis large keystone might have belonged to a triumphal arch at the Forum of Constantine (present-day Çemberlitaş).[1]

Historical affiliationsByzantium 667 BC–510 BC

Persian Empire 512 BC–478 BC

Persian Empire 512 BC–478 BC

Byzantium (Under Athens) 478 BC–404 BC

Byzantium 404 BC–196 CE Roman Empire 196–395 (Capital between 330–395)

Roman Empire 196–395 (Capital between 330–395) Byzantine Empire 395–1204

Byzantine Empire 395–1204 Latin Empire 1204–1261

Latin Empire 1204–1261 Byzantine Empire 1261–1453

Byzantine Empire 1261–1453 Ottoman Empire 1453–1918

Ottoman Empire 1453–1918

Occupation of Istanbul 1918–1923

Occupation of Istanbul 1918–1923 Ankara Government 1923

Ankara Government 1923 Turkey 1923–Present

Turkey 1923–PresentNeolithic artifacts, uncovered by archeologists at the beginning of the 21st century, indicate that Istanbul's historic peninsula was settled as far back as the 6th millennium BCE.[2] That early settlement, important in the spread of the Neolithic Revolution from the Near East to Europe, lasted for almost a millennium before being inundated by rising water levels.[3][2][4][5] The first human settlement on the Asian side, the Fikirtepe mound, is from the Copper Age period, with artifacts dating from 5500 to 3500 BCE,[6] On the European side, near the point of the peninsula (Sarayburnu), there was a Thracian settlement during the early 1st millennium BCE. Modern authors have linked it to the Thracian toponym Lygos,[7] mentioned by Pliny the Elder as an earlier name for the site of Byzantium.[8]

The history of the city proper begins around 660 BCE,[9][10][a] when Greek settlers from Megara established Byzantium on the European side of the Bosporus. The settlers built an acropolis adjacent to the Golden Horn on the site of the early Thracian settlements, fueling the nascent city's economy.[16] The city experienced a brief period of Persian rule at the turn of the 5th century BCE, but the Greeks recaptured it during the Greco-Persian Wars.[17] Byzantium then continued as part of the Athenian League and its successor, the Second Athenian League, before gaining independence in 355 BCE.[18] Long allied with the Romans, Byzantium officially became a part of the Roman Empire in 73 CE.[19] Byzantium's decision to side with the Roman usurper Pescennius Niger against Emperor Septimius Severus cost it dearly; by the time it surrendered at the end of 195 CE, two years of siege had left the city devastated.[20] Five years later, Severus began to rebuild Byzantium, and the city regained—and, by some accounts, surpassed—its previous prosperity.[21]

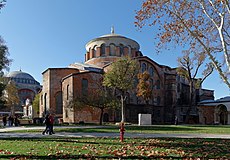

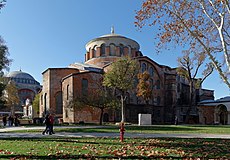

Rise and fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire Originally built by Constantine the Great in the 4th century and later rebuilt by Justinian the Great after the Nika riots in 532, the Hagia Irene is an Eastern Orthodox Church located in the outer courtyard of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. It is one of the few Byzantine era churches that were never converted into mosques; during the Ottoman period it served as Topkapı's principal armoury.

Originally built by Constantine the Great in the 4th century and later rebuilt by Justinian the Great after the Nika riots in 532, the Hagia Irene is an Eastern Orthodox Church located in the outer courtyard of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. It is one of the few Byzantine era churches that were never converted into mosques; during the Ottoman period it served as Topkapı's principal armoury. Originally a church, later a mosque, the 6th-century Hagia Sophia (532–537) by Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great was the largest cathedral in the world for nearly a thousand years, until the completion of the Seville Cathedral (1507) in Spain.

Originally a church, later a mosque, the 6th-century Hagia Sophia (532–537) by Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great was the largest cathedral in the world for nearly a thousand years, until the completion of the Seville Cathedral (1507) in Spain.Constantine the Great effectively became the emperor of the whole of the Roman Empire in September 324.[22] Two months later, he laid out the plans for a new, Christian city to replace Byzantium. As the eastern capital of the empire, the city was named Nova Roma; most called it Constantinople, a name that persisted into the 20th century.[23] On 11 May 330, Constantinople was proclaimed the capital of the Roman Empire, which was later permanently divided between the two sons of Theodosius I upon his death on 17 January 395, when the city became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.[24]

The establishment of Constantinople was one of Constantine's most lasting accomplishments, shifting Roman power eastward as the city became a center of Greek culture and Christianity.[24][25] Numerous churches were built across the city, including Hagia Sophia which was built during the reign of Justinian the Great and remained the world's largest cathedral for a thousand years.[26] Constantine also undertook a major renovation and expansion of the Hippodrome of Constantinople; accommodating tens of thousands of spectators, the hippodrome became central to civic life and, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the center of episodes of unrest, including the Nika riots.[27][28] Constantinople's location also ensured its existence would stand the test of time; for many centuries, its walls and seafront protected Europe against invaders from the east and the advance of Islam.[25] During most of the Middle Ages, the latter part of the Byzantine era, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city on the European continent and at times the largest in the world.[29][30] Constantinople is generally considered to be the center and the "cradle of Orthodox Christian civilization".[31][32]

Constantinople began to decline continuously after the end of the reign of Basil II in 1025. The Fourth Crusade was diverted from its purpose in 1204, and the city was sacked and pillaged by the crusaders.[33] They established the Latin Empire in place of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.[34] Hagia Sophia was converted to a Catholic church in 1204. The Byzantine Empire was restored, albeit weakened, in 1261.[35] Constantinople's churches, defenses, and basic services were in disrepair,[36] and its population had dwindled to a hundred thousand from half a million during the 8th century.[b] After the reconquest of 1261, however, some of the city's monuments were restored, and some, like the two Deesis mosaics in Hagia Sophia and Kariye, were created.[37]

The 6th century Basilica Cistern was built by Justinian the Great.

The 6th century Basilica Cistern was built by Justinian the Great.Various economic and military policies instituted by Andronikos II, such as the reduction of military forces, weakened the empire and left it vulnerable to attack.[38] In the mid-14th-century, the Ottoman Turks began a strategy of gradually taking smaller towns and cities, cutting off Constantinople's supply routes and strangling it slowly.[39] On 29 May 1453, after an eight-week siege (during which the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI, was killed), Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" captured Constantinople.

Ottoman EmpireSultan Mehmed declared Constantinople the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. Hours after the fall of the city, the sultan rode to the Hagia Sophia and summoned an imam to proclaim the Islamic creed, converting the grand cathedral into an imperial mosque due to the city's refusal to surrender peacefully.[40] Mehmed declared himself as the new Kayser-i Rûm (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of the Caesar of Rome) and the Ottoman state was reorganized into an empire.[41][42]

Map of Istanbul in the 16th century by the Ottoman polymath Matrakçı Nasuh

Map of Istanbul in the 16th century by the Ottoman polymath Matrakçı NasuhFollowing the capture of Constantinople,[c] Mehmed II immediately set out to revitalize the city. Cognizant that revitalization would fail without the repopulation of the city, Mehmed II welcomed everyone–foreigners, criminals, and runaways– showing extraordinary openness and willingness to incorporate outsiders that came to define Ottoman political culture.[44] He also invited people from all over Europe to his capital, creating a cosmopolitan society that persisted through much of the Ottoman period.[45] Revitalizing Istanbul also required a massive program of restorations, of everything from roads to aqueducts.[46] Like many monarchs before and since, Mehmed II transformed Istanbul's urban landscape with wholesale redevelopment of the city center.[47] There was a huge new palace to rival, if not overshadow, the old one, a new covered market (still standing as the Grand Bazaar), porticoes, pavilions, walkways, as well as more than a dozen new mosques.[46] Mehmed II turned the ramshackle old town into something that looked like an imperial capital.[47]

Social hierarchy was ignored by the rampant plague, which killed the rich and the poor alike in the 16th century.[48] Money could not protect the rich from all the discomforts and harsher sides of Istanbul.[48] Although the Sultan lived at a safe remove from the masses, and the wealthy and poor tended to live side by side, for the most part Istanbul was not zoned as modern cities are.[48] Opulent houses shared the same streets and districts with tiny hovels.[48] Those rich enough to have secluded country properties had a chance of escaping the periodic epidemics of sickness that blighted Istanbul.[48]

View of the Golden Horn and the Seraglio Point from Galata Tower

View of the Golden Horn and the Seraglio Point from Galata TowerThe Ottoman Dynasty claimed the status of caliphate in 1517, with Constantinople remaining the capital of this last caliphate for four centuries.[49] Suleiman the Magnificent's reign from 1520 to 1566 was a period of especially great artistic and architectural achievement; chief architect Mimar Sinan designed several iconic buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics, stained glass, calligraphy, and miniature flourished.[50] The population of Constantinople was 570,000 by the end of the 18th century.[51]

A period of rebellion at the start of the 19th century led to the rise of the progressive Sultan Mahmud II and eventually to the Tanzimat period, which produced political reforms and allowed new technology to be introduced to the city.[52] Bridges across the Golden Horn were constructed during this period,[53] and Constantinople was connected to the rest of the European railway network in the 1880s.[54] Modern facilities, such as a water supply network, electricity, telephones, and trams, were gradually introduced to Constantinople over the following decades, although later than to other European cities.[55] The modernization efforts were not enough to forestall the decline of the Ottoman Empire.[56]

Two aerial photos showing the Golden Horn and the Bosporus, taken from a German zeppelin on 19 March 1918

Two aerial photos showing the Golden Horn and the Bosporus, taken from a German zeppelin on 19 March 1918 Grand Rue de Pera in Costantinople, 1912. A Nestlé milk advertisement is visible on the building in the background.

Grand Rue de Pera in Costantinople, 1912. A Nestlé milk advertisement is visible on the building in the background.Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the Ottoman Parliament, closed since 14 February 1878, was reopened 30 years later on 23 July 1908, which marked the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.[57] A series of wars in the early 20th century, such as the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), plagued the ailing empire's capital and resulted in the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état, which brought the regime of the Three Pashas.[58]

The Ottoman Empire joined World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 was among the major events which marked the start of the Armenian genocide during WWI.[59] Due to Ottoman and Turkish policies of Turkification and ethnic cleansing, the city's Christian population declined from 450,000 to 240,000 between 1914 and 1927.[60] The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 and the Allies occupied Constantinople on 13 November 1918. The Ottoman Parliament was dissolved by the Allies on 11 April 1920 and the Ottoman delegation led by Damat Ferid Pasha was forced to sign the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.[citation needed]

A view of Bankalar Caddesi (Banks Street) in the late 1920s. Completed in 1892, the Ottoman Bank headquarters is seen at left. In 1995 the Istanbul Stock Exchange moved to İstinye, while numerous Turkish banks have moved to Levent and Maslak.[61]

A view of Bankalar Caddesi (Banks Street) in the late 1920s. Completed in 1892, the Ottoman Bank headquarters is seen at left. In 1995 the Istanbul Stock Exchange moved to İstinye, while numerous Turkish banks have moved to Levent and Maslak.[61]Following the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed VI, was declared persona non grata. Leaving aboard the British warship HMS Malaya on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy, on 16 May 1926. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 24 July 1923, and the occupation of Constantinople ended with the departure of the last forces of the Allies from the city on 4 October 1923.[62] Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the Liberation Day of Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu) and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.[62]

Turkish RepublicOn 29 October 1923 the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the Republic's first President.[63][64]

A 1942 wealth tax assessed mainly on non-Muslims led to the transfer or liquidation of many businesses owned by religious minorities.[65] From the late 1940s and early 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new public squares, boulevards, and avenues were constructed throughout the city, sometimes at the expense of historical buildings.[66] The population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase in the 1970s, as people from Anatolia migrated to the city to find employment in the many new factories that were built on the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis. This sudden, sharp rise in the city's population caused a large demand for housing, and many previously outlying villages and forests became engulfed into the metropolitan area of Istanbul.[67]

^ Cite error: The named reference Forum of Constantine was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ a b Cite error: The named reference BBC-Rainsford-2009 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Algan, O.; Yalçın, M.N.K.; Özdoğan, M.; Yılmaz, Y.C.; Sarı, E.; Kırcı-Elmas, E.; Yılmaz, İ.; Bulkan, Ö.; Ongan, D.; Gazioğlu, C.; Nazik, A.; Polat, M.A.; Meriç, E. (2011). "Holocene coastal change in the ancient harbor of Yenikapı–İstanbul and its impact on cultural history". Quaternary Research. 76 (1): 30. Bibcode:2011QuRes..76...30A. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2011.04.002. S2CID 129280217. ^ "Bu keşif tarihi değiştirir". hurriyet.com.tr. 3 October 2008. ^ "Marmaray kazılarında tarih gün ışığına çıktı". fotogaleri.hurriyet.com.tr. ^ "Cultural Details of Istanbul". Republic of Turkey, Minister of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2007. ^ Janin, Raymond (1964). Constantinople byzantine. Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines. pp. 10ff. ^ "Pliny the Elder, book IV, chapter XI:

"On leaving the Dardanelles we come to the Bay of Casthenes, ... and the promontory of the Golden Horn, on which is the town of Byzantium, a free state, formerly called Lygos; it is 711 miles from Durazzo, ..."". Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2015. ^ Cite error: The named reference Britannica-Istanbul was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, p. 1. ^ Herodotus Histories 4.144, translated in De Sélincourt 2003, p. 288 ^ a b Isaac 1986, p. 199. ^ Roebuck 1959, p. 119, also as mentioned in Isaac 1986, p. 199 ^ Lister 1979, p. 35. ^ Freely 1996, p. 10. ^ Çelik 1993, p. 11. ^ De Souza 2003, p. 88. ^ Freely 1996, p. 20. ^ Freely 1996, p. 22. ^ Grant 1996, pp. 8–10. ^ Limberis 1994, pp. 11–12. ^ Barnes 1981, p. 77 ^ Barnes 1981, p. 212 ^ a b Barnes 1981, p. 222 ^ a b Gregory 2010, p. 63 ^ Klimczuk & Warner 2009, p. 171 ^ Dash, Mike (2 March 2012). "Blue Versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012. ^ Dahmus 1995, p. 117 ^ Cantor 1994, p. 226 ^ Morris 2010, pp. 109–18 ^ Parry, Ken (2009). Christianity: Religions of the World. Infobase Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 9781438106397. ^ Parry, Ken (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 368. ISBN 9781444333619. ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 324–29. ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 330–333. ^ Gregory 2010, p. 340. ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 341–342. ^ "Deesis Mosaic". Hagia Sophia. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2021. ^ Reinert 2002, pp. 258–260. ^ Baynes 1949, p. 47. ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 394–399. ^ Béhar 1999, p. 38. ^ Bideleux & Jeffries 1998, p. 71. ^ Edhem, Eldem. "Istanbul." In: Ágoston, Gábor and Bruce Alan Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing, 21 May 2010. ISBN 1-4381-1025-1, ISBN 9781438110257. Start and CITED: p. 286. "Originally, the name Istanbul referred only to[...]in the 18th century." and "For the duration of Ottoman rule, western sources continued to refer to the city as Constantinople, reserving the name Stamboul for the walled city." and "Today the use of the name[...]is often deemed politically incorrect[...]by most Turks." // (entry ends, with author named, on p. 290) ^ Inalcik, Halil. "The Policy of Mehmed II toward the Greek Population of Istanbul and the Byzantine Buildings of the City." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 23, (1969): 229–49. p. 236 ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 306–07 ^ a b Hughes, Bettany (2018). Istanbul: A Tale of Three Cities. London. ISBN 978-1-78022-473-2.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ^ a b Madden, Thomas F. (7 November 2017). Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossroads of the World. New York. ISBN 978-0-14-312969-1.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ^ a b c d e Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, CA. ISBN 978-1-59884-253-1.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ^ Cite error: The named reference maag1145 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 735–36 ^ Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-785109-9. ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 4–6, 55 ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 87–89 ^ Harter 2005, p. 251 ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 230, 287, 306 ^ Çelik, Zeynep (1986). The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley. Los Angeles. London: University of California Press. p. 37. ^ "Meclis-i Mebusan (Mebuslar Meclisi)". Tarihi Olaylar. ^ Çelik 1993, p. 31 ^ Freedman, Jeri (2009). The Armenian genocide (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4042-1825-3. ^ Globalization, Cosmopolitanism, and the Dönme in Ottoman Salonica and Turkish Istanbul. Marc Baer, University of California, Irvine. ^ "Milestones in Borsa Istanbul History". www.borsaistanbul.com. Retrieved 31 January 2021. ^ a b "6 Ekim İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu". Sözcü. 6 October 2017. ^ Landau 1984, p. 50 ^ Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 39 ^ Ağır, Seven; Artunç, Cihan (2019). "The Wealth Tax of 1942 and the Disappearance of Non-Muslim Enterprises in Turkey". The Journal of Economic History. 79 (1): 201–243. doi:10.1017/S0022050718000724. S2CID 159425371. ^ Keyder 1999, pp. 11–12, 34–36 ^ Efe & Cürebal 2011, pp. 718–719

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- Stay safe As with most European cities, but especially in crowded areas of Istanbul, watch your pockets and travel documents as pickpockets have devised all sorts of strategies to obtain them from you. Do not rely too much on the 'safe' feeling you get from the omnipresence of police.If prices are not on display, always ask beforehand (even for a tea) instead of just ordering something like in Europe. This can be fatal in Istanbul because tourists are constantly overcharged. Unfortunately, often prices are not on display, like in sweet shops or even restaurants. Skip these places or ask for a price knowing what the approximate or fair price is.Istanbul is home to three of the biggest clubs in Turkey and maybe European football: Beşiktaş, Fenerbahçe, and Galatasaray. It is advisable not to wear colours associating yourself with any of the clubs—black&white, navy&yellow, and red&yellow respectively, particularly on the days of matches between the sides due to the fearsome rivalry they share.In Istanbul, most drivers won't abide any rules. Even if you have priority on a road junction, crosswalk, or even during green light, always be aware of your surroundings. Even if you are in a one way road, check both sides before crossing the road....Read moreStay safe As with most European cities, but especially in crowded areas of Istanbul, watch your pockets and travel documents as pickpockets have devised all sorts of strategies to obtain them from you. Do not rely too much on the 'safe' feeling you get from the omnipresence of police.If prices are not on display, always ask beforehand (even for a tea) instead of just ordering something like in Europe. This can be fatal in Istanbul because tourists are constantly overcharged. Unfortunately, often prices are not on display, like in sweet shops or even restaurants. Skip these places or ask for a price knowing what the approximate or fair price is.Istanbul is home to three of the biggest clubs in Turkey and maybe European football: Beşiktaş, Fenerbahçe, and Galatasaray. It is advisable not to wear colours associating yourself with any of the clubs—black&white, navy&yellow, and red&yellow respectively, particularly on the days of matches between the sides due to the fearsome rivalry they share.In Istanbul, most drivers won't abide any rules. Even if you have priority on a road junction, crosswalk, or even during green light, always be aware of your surroundings. Even if you are in a one way road, check both sides before crossing the road. It is common for Turkish drivers to use shortcuts.A major earthquake with epicenter in the nearby Sea of Marmara is expected within the next few decades, so read the earthquake safety article here before you arrive.ScamsRead less

Note, most of the following summaries are already almost 10 years old. Turkey has changed a lot since then, due to modernization, political uproar, the war in Syria, and many other things. Nowadays, the situation is actually far less fierce as it may seem in these outlines. So, relax! Nevertheless, know and read about them, to be aware. The most important ones are the overpriced night clubs and bars, pickpocketing and overly friendly strangers.

Blue Mosque scam "guides"When walking through the gates of the Blue Mosque, beware of smiling, friendly chaps who offer immediately to be your de-facto guide through the mosque and its surrounds; they'd be pretty informative on just about anything relating to the mosque; etiquette, history and Islamic practices. However, they eventually demand a price for their "services", a fee that can be as high as 50 TL. You would be better off booking a private tour online; or not at all, since the mosque is essentially free to all anyway.

Restaurant scamsA notable scam for convincing tourists to visit overpriced restaurants with mediocre food involves the following:

While walking along, you are overtaken by a Turkish man who claims to recognize you from the hotel at which you are staying (e.g. he will tell you that he works there as a waiter or a receptionist). He will ask where you are going. If you are going out for food, he will recommend a restaurant, claiming that it is where he takes his family or friends when they eat out. He may give you some other advice (e.g. the best time to visit the Topkapi palace) to make the conversation feel genuine and friendly. The restaurant he recommends will almost certainly be mediocre or low quality, and the staff there will try to sell you expensive dishes without you realizing. For instance, they may promote dishes which are marked as 'MP' (market price) on the menu, such as 'salt fish' (fish baked in salt), which may cost over 100 TL. They may also serve you additional dishes which you haven't ordered and then add them to the bill for an additional 25-50 TL, together with extra charges for service and tax. One restaurant that seems to be using this scam to get customers is Haci Baba in Sultanahmet.

Bar and club scamsHigh-drink price scams encountered in so-called night-clubs mostly located in Aksaray, Beyazit and Taksim areas. These clubs usually charge overpriced bills, based on a replica of the original menu, or simply on the menu that had been standing upside down on the table. Two or three drinks can already produce a fantasy bill that easily exceeds 1,000 TL.

Also be aware of friendly behaving groups of young men or male-female couples striking up a conversation in the street and inviting you to a "good nightclub they know". This has frequently been reported as a prelude to such a scam. The people in on the scam may offer to take you to dinner first, in order to lower your suspicions. Another way they will try to lure you in is by talking to you in Turkish, and when you mumble back in your language they will be surprised you're not Turkish and immediately will feel the urge to repay you for their accident with a beer.

Another variant of this involves an invitation in Taksim to male tourists to buy them beer (as they were "guests"). At the club, attractive women, also with beers, join them. When the bill comes, the person inviting the tourists denies having said he would pay for the drinks, and a large bill is presented, e.g. for 1500 TL; when the tourists object, burly "security" personnel emerge to accompany the tourists to an ATM (presumably to clean out their bank account). Any bar that looks like it could be a strip club is more than likely a scam joint.

In either of these scams, if you refuse to pay the high prices or try to call the police (dial #155) to file a complaint, the club managers may use physical intimidation to bring the impasse to a close. If you find yourself in such a situation for any reason, you should do whatever they want you to do, pay the bill, buy the things they are forcing you to buy, etc. Try to get out of the situation as soon as possible, go to a safe place and call the police.

Metro Scams and TheftEach metro station has an insufficient amount of fare machines relative to their ridership, and only carry a handful of Istanbul cards. Scam artists camp out here (especially at Taksim Metro), offering to help you buy a ticket only to show you that the machine has run out of reusable metro cards. They will then ask you where you're from, and offer to sell you a card loaded with 100 TRY, for 100-125 TRY as a helpful gesture. When you commence your metro trip, you will learn that the card only contains half or a quarter of that amount. If the machine is not working, you should look for an authorized point of sale near the station, such as a shop or another machine, not the helpful stranger with a dozen cards for sale.

These areas are also prone to pickpocketing because they are chaotic and frequented by tourists. The pickpocketing is generally unrelated to the scam artist operations. You should be especially careful to place your wallet in your front pocket here and to be mindful of your belongings. If someone touches you or places their hand on your shoulder at any point while in or near the Metro system, you are being pickpocketed and you should immediately turn in an unexpected direction, especially if you have belongings in your back pocket.

To avoid these instances at the Taksim Metro where these issues are especially common, buy your tickets or Istanbul Card at the lone fare machine on the bus level.

Water scamsAlso be wary of men in Taksim who splash water on the backs of your neck. When you turn around, they will try to start a fight with you as another man comes in and robs you. These men tend to carry knives and can be very dangerous.

Lira/euro scamsA frequent scam, often in smaller hotels (but it can also happen in a variety of other contexts), is to quote prices in lira and then later, when payment is due, claim the price was given in euros. Hotels which reject payment early in a stay and prefer you to "pay when you leave" should raise suspicions. Hotels which operate this scam often offer excellent service and accommodation at a reasonable price and know most guests will conclude as much and pay without complaint - thus this can be a sign of a good hotel.

Another scam is coin-related and happens just as you're walking into the streets. A Turkish guy holds you and asks where you are from. If you mention a euro-country, the guy wants you to change a €50-note from you into €2-coins he is showing. He is holding the coins stack-wise in his hands. For the trouble, he says he will offer you '30 €2-coins, making €60 in total'. Do not agree with this exchange of money, as the first coin is indeed a €2-coin, but (many of) the rest of the coins will probably be 1-lira coins (looking very similar), but worth only 1/4 of the value of €2.

Many bars in the Taksim area give you counterfeit bills. They are usually well-made and hard to identify as fakes in the dark. One way to verify a bill's authenticity is to check its size against another one. Another is to hold the bill up to a strong light, face side up, and check for an outline of the same face which is on the bill. The value of the bill (20, 50, etc.) should appear next to the outline, light and translucent. If either of these two security features are missing, try to have the bill changed or speak to the police.

Some taxi drivers agree on a price only to tell you your lira bills are counterfeit, or invalid, or have a wrong serial number. This is a scam to have you paying in Euro or USD, usually for a much higher price since they'll claim they don't have change.

ShoebrushSome men will walk around Taksim (or other tourist-frequented areas) with a shoeshine kit, and the brush will fall off. This is a scam to cause some Western tourist with a conscience to pick it up and return it to the owner, who will then express gratitude and offer to shine your shoes for free. While doing that, he will talk about how he is from another city and how he has a sick child. At the end, the shiner will demand a much higher price for the "free" services provided than is the actual market norm. A similar trick is to ask for a cigarette and proceed similarly.

If you actively decide that you would like your shoes shined, then expect to pay not more than 5 TL for both.

Taxi driversTaxis are plentiful in Istanbul and inexpensive by Western European and American standards. They can be picked up at taxi hubs throughout the city or on the streets. Empty cabs on the streets will honk at pedestrians to see if they would like a ride, or cabs can be hailed by pedestrians by making eye contact with the driver and waving. Few taxi drivers speak languages other than Turkish, but do a fair job at deciphering mispronounced location names given by foreign riders. It is advisable to have the name of the destination written down and try to have a map beforehand to show the driver, to avoid any misunderstanding and also potential scams. Though taxis are plentiful, be aware that taxis are harder to find during peak traffic hours and traffic jams and when it is raining and snowing. They are also less frequent during nights, depending on the area and are hard to find after midnight.

Try to avoid using taxis for short distances (5–10 minutes of walk) if possible. Some taxi drivers can be annoyed with this, especially if you called the cab from a taxi hub instead of hailing it from the street. If you want taxis for short distances, just hail them from the street, do not go to the taxi hub.

Few taxis have seatbelts, and some drivers may seem to be reckless. If you wish for the driver to slow down, say "yavash lütfen" (slow please). Your request may or may not be honored.

As in any major city, tourists are more vulnerable to taxi scams than locals. Be aware that taxi drivers use cars affiliated with a particular hub, and that the name and phone number of the hub, as well as the license plate number, are written on the side of each car. Noting or photographing this information may be useful if you run into problems. In general, riding in taxis affiliated with major hotels (Hilton, Marriot, Ritz, etc.) is safe, and it is not necessary to stay in these hotels to use a taxis leaving from their hubs.

Others may take unnecessarily long routes to increase the amount due (although sometimes alternate routes are also taken to avoid Istanbul traffic, which can be very bad). Some scams involve the payment transaction; for example, if the rider pays 50 TL when only 20 TL are needed, the driver may quickly switch it with a 5 TL note and insist that the rest of the 20 TL is still due or may switch the real bill for a fake one and insist that different money be given.

Methods to avoid taxi scams:

1. Sit in the front passenger seat. Watch the meter. Watch the driver's actions (beeping the horn, pumping the brakes, etc.) and note what the taximeter does. While it is rare, some drivers will wire parts of their controls to increase the fare upon activation. If you're with your significant other, do it anyway. Save the cuddling for after the ride. Check if the seal on the taximeter is broken. Use your phone for light. This will make the driver realize that you are cautious. For women it is better to sit in the back seat (where you can see the meter from the middle), as there are occasionally problems with taxi drivers getting overly friendly, and sitting in the front is a sign that a woman welcomes such behavior.

2. Ask "How much to go to...?" (basic English is understood), before getting in the taxi. Price will be quite accurate to the one in the taximeter at the end of the ride. If the price sounds ok for you, get in the cab and tell them to put the Taximeter on. The rate they are applying is same during night and day.

3. Know the route. If you have a chance, find a map and demand that the driver take your chosen route to the destination. Oftentimes they will drive the long way or pretend not to know where you're going in order to get more money out of you. If the driver claims not to know the route to a major landmark or gathering place, refuse his services as he is likely lying.

4. Choose an elderly driver. Elderly taxi drivers are less likely to cheat passengers.

5. Let taxi driver see money on your hands and show values and take commitment on it. This is 50 lira. OK? Take this 50 lira and give 30 lira back OK?. This guarantees your money value. Otherwise, your 50 lira can be 5 lira immediately on his hands. Try to have always 10 lira or 20 lira bills in your wallet. This makes money scams in general more difficult. If you realize that the driver tried to use the 50 lira to 5 lira trick on you, call the police (#155) immediately and write down the license plate. If a driver claims not to have change, you may want to consider sitting in the taxi and pointing to a nearby shop to have them break their bills there. This will usually cause them to magically find the necessary change, or frustrate them into accepting a lower fare.

6. Create a big scene if there is a problem. If you are absolutely positive you have been subject to a scam, threaten to or call the police and, if you feel it will help, start yelling. Taxi drivers will only rip off those they think will fall for it; creating a scene draws attention to them and will make it easier to pay the correct rate.

OverpricingWatch the menu carefully in street cafes for signs that prices are not discriminatory — if prices are clearly over-inflated, simply leave. A good indication of over inflation is the circulation of two different types of menu — the "foreigner" menu is typically printed on a laminated card with menu prices written in laundry marker/texta, i.e., prices not be printed; in these cases, expect that prices for foreigners will be highly inflated (300% or higher).

While this is not really a problem in Beyoğlu or Ortaköy, avoiding the open air cafes toward the rear courtyard of the Spice Bazaar (Sultanahmet) is wise. The area immediately north of the Spice Bazaar is also crawling with touts for these 'infamous' cafes.

Having nargile (water pipe) is a famous activity in Istanbul,Tophane (top-hane) is a famous location for this activity where a huge number of nargile shops are available and can easily be reached by the tram, avoiding a place called "Ali Baba" in Tophane is wise, usually you will be served there with plates you did not ask for like a nuts plate, and expect to have a bill of around US$50 for your nargile!

StalkingMen intent on stalking foreign women may be present in tourist locations. Such men may presume that foreigners have a lot of money or liberal values and may approach foreign women in a flirtatious or forward manner looking for sex or for money (either by theft or selling over-priced goods). If you are being harassed, use common sense and go to where other people are; often this is the nearest store. Creating a public scene will deter many stalkers, and these phrases may be useful in such cases:

İmdat! – "Help!" Ayıp! – "Rude!" Bırak beni! – "Leave me alone!" Dur! – "Stop!" Gider misin?! – "Will you go?!"Or to really ruin him:

Beni takip etme! – "Stop stalking me!" Polisi arıyorum – "I'm calling the cops!"Occasionally try not to use Turkish as the stalker will like it more, just scream and run and find a safer place with crowd and police.

Tourism PoliceIstanbul PD has a "Tourism Police" department where travelers may report passport loss and theft or any other criminal activity by which they are victimized. They have an office in Sultanahmet and can reportedly speak English, German, French, and Arabic.

Tourism Police (Turizm Polisi), Yerebatan Caddesi 6, Sultanahmet (in the yellow wooden building between Hagia Sophia and the entrance of Basilica Cistern, few meters away from each), ☏ +90 212 527 45 03, fax: +90 212 512 76 76.