ایران

IranContext of Iran

Iran, also known as Persia and officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmenistan to the north, by Afghanistan and Pakistan to the east, and by the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf to the south. It covers an area of 1.64 million square kilometres (0.63 million square miles), making it the 17th-largest country. Iran has an estimated population of 86.8 million, making it the 17th-most populous country in the world, and the second-largest in the Middle East. Its largest cities, in descending order, are the capital Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Karaj, Shiraz, and Tabriz.

The country is home to one of the world's oldest civilizations, beginning with the formation of the Elamite kingdoms in the fourth millennium BC. It was first unified by the Medes, an...Read more

Iran, also known as Persia and officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmenistan to the north, by Afghanistan and Pakistan to the east, and by the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf to the south. It covers an area of 1.64 million square kilometres (0.63 million square miles), making it the 17th-largest country. Iran has an estimated population of 86.8 million, making it the 17th-most populous country in the world, and the second-largest in the Middle East. Its largest cities, in descending order, are the capital Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Karaj, Shiraz, and Tabriz.

The country is home to one of the world's oldest civilizations, beginning with the formation of the Elamite kingdoms in the fourth millennium BC. It was first unified by the Medes, an ancient Iranian people, in the seventh century BC, and reached its territorial height in the sixth century BC, when Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid Persian Empire, which became one of the largest empires in history and a superpower. The Achaemenid Empire fell to Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC and was subsequently divided into several Hellenistic states. An Iranian rebellion established the Parthian Empire in the third century BC, which was succeeded in the third century AD by the Sassanid Empire, a major world power for the next four centuries. Arab Muslims conquered the empire in the seventh century AD, which led to the Islamization of Iran. It subsequently became a major center of Islamic culture and learning, with its art, literature, philosophy, and architecture spreading across the Muslim world and beyond during the Islamic Golden Age. Over the next two centuries, a series of native Iranian Muslim dynasties emerged before the Seljuk Turks and the Mongols conquered the region. In the 15th century, the native Safavids re-established a unified Iranian state and national identity, and converted the country to Shia Islam. Under the reign of Nader Shah in the 18th century, Iran presided over the most powerful military in the world, though by the 19th century, a series of conflicts with the Russian Empire led to significant territorial losses. The early 20th century saw the Persian Constitutional Revolution. Efforts to nationalize its fossil fuel supply from Western companies led to an Anglo-American coup in 1953, which resulted in greater autocratic rule under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and growing Western political influence. He went on to launch a far-reaching series of reforms in 1963. After the Iranian Revolution, the current Islamic Republic was established in 1979 by Ruhollah Khomeini, who became the country's first Supreme Leader.

The government of Iran is an Islamic theocracy that includes some elements of a presidential system, with the ultimate authority vested in an autocratic "Supreme Leader"; a position held by Ali Khamenei since Khomeini's death in 1989. The Iranian government is authoritarian, and has attracted widespread criticism for its significant constraints and abuses against human rights and civil liberties, including several violent suppressions of mass protests, unfair elections, and limited rights for women and for children. It is also a focal point for Shia Islam within the Middle East, countering the long-existing Arab and Sunni hegemony within the region. Since the Iranian Revolution, the country is widely considered to be the most determined adversary of Israel and also of Saudi Arabia. Iran is also considered to be one of the biggest players within Middle Eastern affairs, with its government being involved both directly and indirectly in the majority of modern Middle Eastern conflicts.

Iran is a regional and middle power, with a geopolitically strategic location in the Asian continent. It is a founding member of the United Nations, the ECO, the OIC, and the OPEC. It has large reserves of fossil fuels—including the second-largest natural gas supply and the third-largest proven oil reserves. The country's rich cultural legacy is reflected in part by its 26 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Historically a multi-ethnic country, Iran remains a pluralistic society comprising numerous ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups, with the largest of these being Persians, Azeris, Kurds, Mazandaranis, and Lurs.

More about Iran

- Currency Iranian rial

- Native name ایران

- Calling code +98

- Internet domain .ir

- Mains voltage 220V/50Hz

- Democracy index 2.2

- Population 86758304

- Area 1648195

- Driving side right

- Prehistory

Read more

PrehistoryRead lessA cave painting in Doushe cave, Lorestan from the 2nd millennium BC.[1]The earliest attested archaeological artifacts in Iran, like those excavated at Kashafrud and Ganj Par in northern Iran, confirm a human presence in Iran since the Lower Paleolithic.[2] Iran's Neanderthal artifacts from the Middle Paleolithic have been found mainly in the Zagros region, at sites such as Warwasi and Yafteh.[3][4][page needed] From the tenth to the seventh millennium BC, early agricultural communities began to flourish in and around the Zagros region in western Iran, including Chogha Golan,[5][6] Chogha Bonut,[7][8] and Chogha Mish.[9][10][page needed][11]

The occupation of grouped hamlets in the area of Susa, as determined by radiocarbon dating, ranges from 4395–3955 to 3680–3490 BC.[12] There are dozens of prehistoric sites across the Iranian Plateau, pointing to the existence of ancient cultures and urban settlements in the fourth millennium BC.[11][13][14] During the Bronze Age, the territory of present-day Iran was home to several civilizations,[15][16] including Elam, Jiroft, and Zayanderud. Elam, the most prominent of these civilizations, developed in the southwest alongside those in Mesopotamia, and continued its existence until the emergence of the Iranian empires. The advent of writing in Elam was paralleled to Sumer, and the Elamite cuneiform was developed since the third millennium BC.[17]

From the 34th to the 20th century BC, northwestern Iran was part of the Kura-Araxes culture, which stretched into the neighboring Caucasus and Anatolia. Since the earliest second millennium BC, Assyrians settled in swaths of western Iran and incorporated the region into their territories.

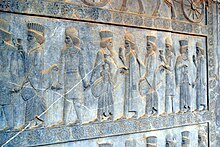

Classical antiquityA bas-relief at Persepolis, depicting the united Medes and PersiansBy the second millennium BC, the ancient Iranian peoples arrived in what is now Iran from the Eurasian Steppe,[18] rivaling the native settlers of the region.[19][20] As the Iranians dispersed into the wider area of Greater Iran and beyond, the boundaries of modern-day Iran were dominated by Median, Persian, and Parthian tribes.

From the late tenth to the late seventh century BC, the Iranian peoples, together with the "pre-Iranian" kingdoms, fell under the domination of the Assyrian Empire, based in northern Mesopotamia.[21][page needed] Under king Cyaxares, the Medes and Persians entered into an alliance with Babylonian ruler Nabopolassar, as well as the fellow Iranian Scythians and Cimmerians, and together they attacked the Assyrian Empire. The civil war ravaged the Assyrian Empire between 616 and 605 BC, thus freeing their respective peoples from three centuries of Assyrian rule.[21] The unification of the Median tribes under king Deioces in 728 BC led to the foundation of the Median Empire which, by 612 BC, controlled almost the entire territory of present-day Iran and eastern Anatolia.[22] This marked the end of the Kingdom of Urartu as well, which was subsequently conquered and dissolved.[23][24]

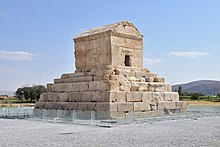

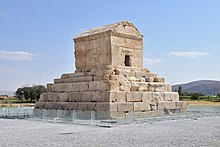

Tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, in Pasargadae

Tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, in PasargadaeIn 550 BC, Cyrus the Great, the son of Mandane and Cambyses I, took over the Median Empire, and founded the Achaemenid Empire by unifying other city-states. The conquest of Media was a result of what is called the Persian Revolt. The brouhaha was initially triggered by the actions of the Median ruler Astyages, and was quickly spread to other provinces as they allied with the Persians. Later conquests under Cyrus and his successors expanded the empire to include Lydia, Babylon, Egypt, parts of the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper, as well as the lands to the west of the Indus and Oxus rivers.

539 BC was the year in which Persian forces defeated the Babylonian army at Opis, and marked the end of around four centuries of Mesopotamian domination of the region by conquering the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Cyrus entered Babylon and presented himself as a traditional Mesopotamian monarch. Subsequent Achaemenid art and iconography reflect the influence of the new political reality in Mesopotamia.[25][26][27]

The Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC) around the time of Darius the Great and Xerxes I

The Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC) around the time of Darius the Great and Xerxes I The Parthian Empire (247 BC–224 AD) in 94 BC at its greatest extent, during the reign of Mithridates II

The Parthian Empire (247 BC–224 AD) in 94 BC at its greatest extent, during the reign of Mithridates IIAt its greatest extent, the Achaemenid Empire included territories of modern-day Iran, Republic of Azerbaijan (Arran and Shirvan), Armenia, Georgia, Turkey (Anatolia), much of the Black Sea coastal regions, northeastern Greece and southern Bulgaria (Thrace), northern Greece and North Macedonia (Paeonia and Macedon), Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories, all significant population centers of ancient Egypt as far west as Libya, Kuwait, northern Saudi Arabia, parts of the United Arab Emirates and Oman, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and much of Central Asia, making it the largest empire the world had yet seen.[26]

It is estimated that in 480 BC, 50 million people lived in the Achaemenid Empire.[28][29] The empire at its peak ruled over 44% of the world's population, the highest such figure for any empire in history.[30]

The Achaemenid Empire is noted for the release of the Jewish exiles in Babylon,[31] building infrastructures such as the Royal Road and the Chapar (postal service), and the use of an official language, Imperial Aramaic, throughout its territories.[26] The empire had a centralized, bureaucratic administration under the emperor, a large professional army, and civil services, inspiring similar developments in later empires.[32][33]

Eventual conflict on the western borders began with the Ionian Revolt, which erupted into the Greco-Persian Wars and continued through the first half of the fifth century BC, and ended with the withdrawal of the Achaemenids from all of the territories in the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper.[34]

In 334 BC, Alexander the Great invaded the Achaemenid Empire, defeating the last Achaemenid emperor, Darius III, at the Battle of Issus. Following the premature death of Alexander, Iran came under the control of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. In the middle of the second century BC, the Parthian Empire rose to become the main power in Iran, and the century-long geopolitical arch-rivalry between the Romans and the Parthians began, culminating in the Roman–Parthian Wars. The Parthian Empire continued as a feudal monarchy for nearly five centuries, until 224 CE, when it was succeeded by the Sasanian Empire.[35] Together with their neighboring arch-rival, the Roman-Byzantines, they made up the world's two most dominant powers at the time, for over four centuries.[36][37]

The Sasanians established an empire within the frontiers achieved by the Achaemenids, with their capital at Ctesiphon. Late antiquity is considered one of Iran's most influential periods, as under the Sasanians,[38] their influence reached the culture of ancient Rome (and through that as far as Western Europe),[39][40] Africa,[41] China, and India,[42] and played a prominent role in the formation of the medieval art of both Europe and Asia.[43][36][37]

Most of the era of the Sasanian Empire was overshadowed by the Roman–Persian Wars, which raged on the western borders at Anatolia, the Western Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, for over 700 years. These wars ultimately exhausted both the Romans and the Sasanians and led to the defeat of both by the Muslim invasion.[citation needed]

Throughout the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian eras, several offshoots of the Iranian dynasties established eponymous branches in Anatolia and the Caucasus, including the Pontic Kingdom, the Mihranids, and the Arsacid dynasties of Armenia, Iberia (Georgia), and Caucasian Albania (present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan).[citation needed]

Medieval periodThe prolonged Byzantine–Sasanian wars, most importantly the climactic war of 602–628, as well as the social conflict within the Sasanian Empire, opened the way for an Arab invasion of Iran in the seventh century.[44][45] The empire was initially defeated by the Rashidun Caliphate, which was succeeded by the Umayyad Caliphate, followed by the Abbasid Caliphate. A prolonged and gradual process of state-imposed Islamization followed, which targeted Iran's then Zoroastrian majority and included religious persecution,[46][47][48] demolition of libraries[49] and fire temples,[50] a special tax penalty ("jizya"),[51][52] and language shift.[53][54]

In 750, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads.[55] Arabs Muslims and Persians of all strata made up the rebel army, which was united by the converted Persian Muslim, Abu Muslim.[56][57][58] In their struggle for power, the society in their times gradually became cosmopolitan and the old Arab simplicity and aristocratic dignity, bearing and prestige were lost. Persians and Turks began to replace the Arabs in most fields. The fusion of the Arab nobility with the subject races, the practice of polygamy and concubinage, made for a social amalgam wherein loyalties became uncertain and a hierarchy of officials emerged, a bureaucracy at first Persian and later Turkish which decreased Abbasid prestige and power for good.[59]

After two centuries of Arab rule, semi-independent and independent Iranian kingdoms—including the Tahirids, Saffarids, Samanids, and Buyids—began to appear on the fringes of the declining Abbasid Caliphate.[60]

Tomb of Hafez, a medieval Persian poet whose works are regarded as a pinnacle in Persian literature and have left a considerable mark on later Western writers, most notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[61][62][63]

Tomb of Hafez, a medieval Persian poet whose works are regarded as a pinnacle in Persian literature and have left a considerable mark on later Western writers, most notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[61][62][63]The blossoming literature, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and art of Iran became major elements in the formation of a new age for the Iranian civilization, during a period known as the Islamic Golden Age.[64][65] The Islamic Golden Age reached its peak by the 10th and 11th centuries, during which Iran was the main theater of scientific activities.[66]

The tenth century saw a mass migration of Turkic tribes from Central Asia into the Iranian Plateau.[67] Turkic tribesmen were first used in the Abbasid army as mamluks (slave-warriors), replacing Iranian and Arab elements within the army.[56] As a result, the Mamluks gained significant political power. In 999, large portions of Iran came briefly under the rule of the Ghaznavids, whose rulers were of mamluk Turkic origin, and longer subsequently under the Seljuk and Khwarezmian empires.[67] The Seljuks subsequently gave rise to the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia, while taking their thoroughly Persianized identity with them.[68][69] The result of the adoption and patronage of Persian culture by Turkish rulers was the development of a distinct Turco-Persian tradition.

From 1219 to 1221, under the Khwarazmian Empire, Iran suffered a devastating invasion by the Mongol Empire army of Genghis Khan. According to Steven R. Ward, "Mongol violence and depredations killed up to three-fourths of the population of the Iranian Plateau, possibly 10 to 15 million people. Some historians have estimated that Iran's population did not again reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century."[70] Most modern historians either outright dismiss or are highly skeptical of such statistics of colossal magnitude pertaining the Mongol onslaught on the Khwarazmian empire, mainland Iran and other Muslim regions and deem them to be exaggerations by Muslim chroniclers of that era (whose recordings were naturally of an anti-Mongol bent). Indeed, as far as the Iranian plateau was concerned, the bulk of the Mongol onslaught and battles were in the northeast of what is modern-day Iran, such as in the cities of Nishapur and Tus.[71][72][73]

Following the fracture of the Mongol Empire in 1256, Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, established the Ilkhanate in Iran. In 1357, the capital Tabriz was occupied by the Golden Horde khan Jani Beg and the centralized power collapsed, resulting in the emergence of rivaling dynasties. In 1370, yet another conqueror, Timur from Transoxiana, took control over Persia, establishing the Timurid Empire which lasted for another 156 years. In 1387, Timur ordered the complete massacre of Isfahan, reportedly killing 70,000 citizens.[74] The Ilkhans and the Timurids soon came to adopt the ways and customs of the Iranians, surrounding themselves with a culture that was distinctively Iranian.[75]

Early modern period Safavids Venetian portrait, kept at the Uffizi, of Ismail I, the founder of the Safavid Empire

Venetian portrait, kept at the Uffizi, of Ismail I, the founder of the Safavid EmpireBy the 1500s, Ismail I of Ardabil established the Safavid Empire,[76][77] with his capital at Tabriz.[67] Beginning with Azerbaijan, he subsequently extended his authority over all of the Iranian territories, and established an intermittent Iranian hegemony over the vast relative regions, reasserting the Iranian identity within large parts of Greater Iran.[78] Iran was predominantly Sunni,[79] but Ismail instigated a forced conversion to the Shia branch of Islam,[80][77][81][82] spreading throughout the Safavid territories in the Caucasus, Iran, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia. As a result, modern-day Iran is the only official Shia nation of the world, with it holding an absolute majority in Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan, having there the first and the second highest number of Shia inhabitants by population percentage in the world.[83][84] Meanwhile, the centuries-long geopolitical and ideological rivalry between Safavid Iran and the neighboring Ottoman Empire led to numerous Ottoman–Iranian wars.[70]

A portrait of Abbas I, the powerful, pragmatic Safavid ruler who reinforced Iran's military, political, and economic power

A portrait of Abbas I, the powerful, pragmatic Safavid ruler who reinforced Iran's military, political, and economic powerThe Safavid era peaked in the reign of Abbas I (1587–1629),[70][85] surpassing their Turkish archrivals in strength, and making Iran a leading science and art hub in western Eurasia. The Safavid era saw the start of mass integration from Caucasian populations into new layers of the society of Iran, as well as mass resettlement of them within the heartlands of Iran, playing a pivotal role in the history of Iran for centuries onwards. Following a gradual decline in the late 1600s and the early 1700s, which was caused by internal conflicts, the continuous wars with the Ottomans, and the foreign interference (most notably the Russian interference), the Safavid rule was ended by the Pashtun rebels who besieged Isfahan and defeated Sultan Husayn in 1722.

AfsharidsIn 1729, Nader Shah, a chieftain and military genius from Khorasan, successfully drove out and conquered the Pashtun invaders. He subsequently took back the annexed Caucasian territories which were divided among the Ottoman and Russian authorities by the ongoing chaos in Iran. During the reign of Nader Shah, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sasanian Empire, reestablishing the Iranian hegemony all over the Caucasus, as well as other major parts of the west and central Asia, and briefly possessing what was arguably the most powerful empire at the time.[86][87][88][86]

Statue of Nader Shah, the first Afsharid ruler of Iran, at his Tomb

Statue of Nader Shah, the first Afsharid ruler of Iran, at his TombNader Shah invaded India and sacked far off Delhi by the late 1730s. His territorial expansion, as well as his military successes, went into a decline following the final campaigns in the Northern Caucasus against then revolting Lezgins. The assassination of Nader Shah sparked a brief period of civil war and turmoil, after which Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty came to power in 1750, bringing a period of relative peace and prosperity.[70]

ZandsCompared to its preceding dynasties, the geopolitical reach of the Zand dynasty was limited. Many of the Iranian territories in the Caucasus gained de facto autonomy and were locally ruled through various Caucasian khanates. However, despite the self-ruling, they all remained subjects and vassals to the Zand king.[89] Another civil war ensued after the death of Karim Khan in 1779, out of which Agha Mohammad Khan emerged, founding the Qajar dynasty in 1794.

QajarsIn 1795, following the disobedience of the Georgian subjects and their alliance with the Russians, the Qajars captured Tbilisi by the Battle of Krtsanisi, and drove the Russians out of the entire Caucasus, reestablishing the Iranian suzerainty over the region.

A map showing the 19th-century northwestern borders of Iran, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and the Republic of Azerbaijan, before being ceded to the neighboring Russian Empire by the Russo-Iranian wars

A map showing the 19th-century northwestern borders of Iran, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and the Republic of Azerbaijan, before being ceded to the neighboring Russian Empire by the Russo-Iranian warsThe Russo-Iranian wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828 resulted in large irrevocable territorial losses for Iran in the Caucasus, comprising all of the South Caucasus and Dagestan, which made part of the very concept of Iran for centuries,[87] and thus substantial gains for the neighboring Russian Empire.

As a result of the 19th-century Russo-Iranian wars, the Russians took over the Caucasus, and Iran irrevocably lost control over its integral territories in the region (comprising modern-day Dagestan, Georgia, Armenia, and Republic of Azerbaijan), which got confirmed per the treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay.[88][90] The area to the north of Aras River, among which the contemporary Republic of Azerbaijan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Armenia are located, were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[88][91][92][93][94][95][96] The weakening of Persia made it into a victim of the colonial struggle between Russia and Britain known as the Great Game.[97] Especially after the treaty of Turkmenchay, Russia was the dominant force in Iran,[98] while the Qajars would also play a role in several 'Great Game' battles such as the sieges of Herat in 1837 and 1856.

As Iran shrank, many South Caucasian and North Caucasian Muslims moved towards Iran,[99][100] especially until the aftermath of the Circassian Genocide,[100] and the decades afterwards, while Iran's Armenians were encouraged to settle in the newly incorporated Russian territories,[101][102][103] causing significant demographic shifts.

Around 1.5 million people—20 to 25% of the population of Iran—died as a result of the Great Famine of 1870–1872.[104]

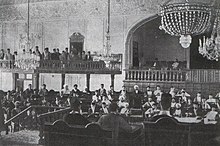

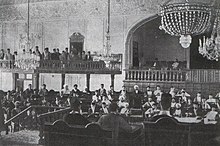

The first national Iranian Parliament was established in 1906 during the Persian Constitutional Revolution.

The first national Iranian Parliament was established in 1906 during the Persian Constitutional Revolution.Between 1872 and 1905, a series of protests took place in response to the sale of concessions to foreigners by Qajar monarchs Naser-ed-Din and Mozaffar-ed-Din, and led to the Constitutional Revolution in 1905. The first Iranian constitution and the first national parliament of Iran were founded in 1906, through the ongoing revolution. The Constitution included the official recognition of Iran's three religious minorities, namely Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians,[105] which has remained a basis in the legislation of Iran since then. The struggle related to the constitutional movement was followed by the Triumph of Tehran in 1909, when Mohammad Ali Shah was defeated and forced to abdicate. In 1907, the Anglo-Russian Convention divided Qajar Iran into influence zones, formalising many of the concessions. On the pretext of restoring order, the Russians occupied northern Iran and the city of Tabriz and maintained a military presence in the region for years to come. But this did not put an end to the civil uprisings and was soon followed by Mirza Kuchik Khan's Jungle Movement against both the Qajar monarchy and foreign invaders.

Reza Shah, the first Pahlavi king of Iran, in military uniform

Reza Shah, the first Pahlavi king of Iran, in military uniformDespite Iran's neutrality during World War I, the Ottoman, Russian and British empires occupied the territory of western Iran and fought the Persian Campaign before fully withdrawing their forces in 1921. At least 2 million Persian civilians died either directly in the fighting, the Ottoman perpetrated anti-Christian genocides or the war-induced famine of 1917–1919. A large number of Iranian Assyrian and Iranian Armenian Christians, as well as those Muslims who tried to protect them, were victims of mass murders committed by the invading Ottoman troops, notably in and around Khoy, Maku, Salmas, and Urmia.[106][107][108][109][110]

Apart from the rule of Agha Mohammad Khan, the Qajar rule is characterized as a century of misrule.[67] The inability of Qajar Iran's government to maintain the country's sovereignty during and immediately after World War I led to the British directed 1921 Persian coup d'état and Reza Shah's establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah, became the new Prime Minister of Iran and was declared the new monarch in 1925.

PahlavisIn the midst of World War II, in June 1941, Nazi Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and invaded the Soviet Union, Iran's northern neighbor. The Soviets quickly allied themselves with the Allied countries and in July and August 1941 the British demanded that the Iranian government expel all Germans from Iran. Reza Shah refused to expel the Germans and on 25 August 1941, the British and Soviets launched a surprise invasion and Reza Shah's government quickly surrendered.[111] The invasion's strategic purpose was to secure a supply line to the USSR (later named the Persian Corridor), secure the oil fields and Abadan Refinery (of the UK-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company), prevent a German advance via Turkey or the USSR on Baku's oil fields, and limit German influence in Iran. Following the invasion, on 16 September 1941 Reza Shah abdicated and was replaced by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, his 21-year-old son.[112][113][114]

The Allied "Big Three" at the 1943 Tehran Conference

The Allied "Big Three" at the 1943 Tehran ConferenceDuring the rest of World War II, Iran became a major conduit for British and American aid to the Soviet Union and an avenue through which over 120,000 Polish refugees and Polish Armed Forces fled the Axis advance.[115] At the 1943 Tehran Conference, the Allied "Big Three"—Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill—issued the Tehran Declaration to guarantee the post-war independence and boundaries of Iran. However, at the end of the war, Soviet troops remained in Iran and established two puppet states in north-western Iran, namely the People's Government of Azerbaijan and the Republic of Mahabad. This led to the Iran crisis of 1946, one of the first confrontations of the Cold War, which ended after oil concessions were promised to the USSR and Soviet forces withdrew from Iran proper in May 1946. The two puppet states were soon overthrown, and the oil concessions were later revoked.[116][117]

1951–1978: Mosaddegh, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the Imperial Family during the coronation ceremony of the Shah of Iran in 1967

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the Imperial Family during the coronation ceremony of the Shah of Iran in 1967In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh was appointed as the Prime Minister of Pahlavi Iran. After the nationalization of Iran's oil industry, he became enormously popular. He was deposed in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, an Anglo-American covert operation that marked the first time the United States had participated in an overthrow of a foreign government during the Cold War.[118]

After the coup, the Shah became increasingly autocratic and sultanistic, and Iran entered a decades-long phase of controversially close relations with the United States and some other foreign governments.[119] While the Shah increasingly modernized Iran and claimed to retain it as a fully secular state,[120] arbitrary arrests and torture by his secret police, the SAVAK, were used for crushing all forms of political opposition.[121]

Ruhollah Khomeini, a radical Muslim cleric,[122] became an active critic of the Shah's far-reaching series of reforms known as the White Revolution. Khomeini publicly denounced the government, and was arrested and imprisoned for 18 months. After his release in 1964, he refused to apologize and was eventually sent into exile.

Due to the 1973 spike in oil prices, the economy of Iran was flooded with foreign currency, which caused inflation. By 1974, the economy of Iran was experiencing a double-digit inflation rate, and despite the many large projects to modernize the country, corruption was rampant and caused large amounts of waste. By 1975 and 1976, an economic recession led to an increased unemployment rate, especially among millions of youths who had migrated to the cities of Iran looking for construction jobs during the boom years of the early 1970s. By the late 1970s, many of these people opposed the Shah's regime and began organizing and joining the protests against it.[123]

After the 1979 Iranian Revolution Ruhollah Khomeini's return to Iran on 1 February 1979

Ruhollah Khomeini's return to Iran on 1 February 1979The 1979 Revolution, later known as the Islamic Revolution,[124][125][126][127][120][128] began in January 1978 with the first major demonstrations against the Shah.[129] After a year of strikes and demonstrations paralyzing the country and its economy, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled to the United States, and Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile to Tehran in February 1979, forming a new government.[130] After holding a referendum, Iran officially became an Islamic republic in April 1979.[131] A second referendum in December 1979 approved a theocratic constitution.[132]

The immediate nationwide uprisings against the new government began with the 1979 Kurdish rebellion and the Khuzestan uprisings, along with the uprisings in Sistan and Baluchestan and other areas. Over the next several years, these uprisings were subdued violently by the new Islamic government. The new government began purging itself of the non-Islamist political opposition, as well as of those Islamists who were not considered radical enough. Although both nationalists and Marxists had initially joined with Islamists to overthrow the Shah, tens of thousands were executed by the new regime afterward.[133] Following Khomeini's order to purge the new government of any remaining officials still loyal to the exiled Shah, many former ministers and officials in the Shah's government, including former prime minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, were executed.

On 4 November 1979, after the United States refusal for the extradition of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to the new government, a group of Muslim students seized the United States Embassy and took the embassy with 52 personnel and citizens hostage .[134] Attempts by the Jimmy Carter administration to negotiate for the release of the hostages, and a failed rescue attempt, helped with the falling popularity of Carter among the US citizens and it pushed him out of the presidential office and brought Ronald Reagan to power. On Jimmy Carter's final day in office, the last hostages were finally set free due to the Algiers Accords. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left the United States for Egypt, where he died of complications from cancer only months later, on 27 July 1980.

The Cultural Revolution began in 1980, with an initial closure of universities for three years, in order to perform an inspection and clean up in the cultural policy of the education and training system.[citation needed]

An Iranian soldier wearing a gas mask on the front line during the Iran–Iraq War

An Iranian soldier wearing a gas mask on the front line during the Iran–Iraq WarOn 22 September 1980, the Iraqi army invaded the western Iranian province of Khuzestan, initiating the Iran–Iraq War. Although the forces of Saddam Hussein made several early advances, by mid-1982, the Iranian forces successfully managed to drive the Iraqi army back into Iraq. In July 1982, with Iraq thrown on the defensive, the regime of Iran decided to invade Iraq and conducted countless offensives to conquer Iraqi territory and capture cities, such as Basra. The war continued until 1988, when the Iraqi army defeated the Iranian forces inside Iraq and pushed the remaining Iranian troops back across the border. Subsequently, Khomeini accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations. The total Iranian casualties in the war were estimated to be 123,220–160,000 KIA, 60,711 MIA, and 11,000–16,000 civilians killed.[135][136]

The Green Movement's Silent Demonstration during the 2009–10 Iranian election protests

The Green Movement's Silent Demonstration during the 2009–10 Iranian election protestsFollowing the Iran–Iraq War, in 1989, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and his administration concentrated on a pragmatic pro-business policy of rebuilding and strengthening the economy without making any dramatic break with the ideology of the revolution. In 1997, Rafsanjani was succeeded by moderate reformist Mohammad Khatami, whose government attempted, unsuccessfully, to make the country more free and democratic.[137]

The 2005 presidential election brought conservative populist candidate, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, to power.[138] By the time of the 2009 Iranian presidential election, the Interior Ministry announced incumbent President Ahmadinejad had won 62.63% of the vote, while Mir-Hossein Mousavi had come in second place with 33.75%.[139][140] The election results were widely disputed,[141][142] and resulted in widespread protests, both within Iran and in major cities outside the country,[143][144] and the creation of the Iranian Green Movement.

Hassan Rouhani was elected as the president on 15 June 2013, defeating Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and four other candidates.[145][146] The electoral victory of Rouhani relatively improved the relations of Iran with other countries.[147]

The 2017–18 Iranian protests were initiated on 31 December 2017 and continued for months.

The 2017–18 Iranian protests were initiated on 31 December 2017 and continued for months.The 2017–18 Iranian protests swept across the country against the government and its longtime Supreme Leader in response to the economic and political situation.[148] The scale of protests throughout the country and the number of people participating were significant,[149] and it was formally confirmed that thousands of protesters were arrested.[150] The 2019–20 Iranian protests started on 15 November in Ahvaz, spreading across the country within hours, after the government announced increases in the fuel price of up to 300%.[151] A week-long total Internet shutdown throughout the country marked one of the most severe Internet blackouts in any country, and in the bloodiest governmental crackdown of the protestors in the history of Islamic Republic,[152] tens of thousands were arrested and hundreds were killed within a few days according to multiple international observers, including Amnesty International.[153]

On 3 January 2020, the revolutionary guard's general, Qasem Soleimani, was assassinated by the United States in Iraq, which considerably heightened the existing tensions between the two countries.[154] Three days after, Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps launched a retaliatory attack on US forces in Iraq and by accident shot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, killing all members on board the plane and leading to nation-wide protests. An international investigation led to the government admitting to the shootdown of the plane by a surface-to-air missile after three days of denial, calling it a "human error".[155][156]

Protests against the government began on 16 September 2022 following the death of Mahsa Amini after being arrested by the Guidance Patrol.[157][158][159]

^ M, Dattatreya; al (14 March 2016). "Researchers Discover 7,000-Year-Old Cemetery in Khuzestan, Iran". Realm of History. Retrieved 2 June 2019. ^ Biglari, Fereidoun; Saman Heydari; Sonia Shidrang. "Ganj Par: The first evidence for Lower Paleolithic occupation in the Southern Caspian Basin, Iran". Antiquity. Retrieved 27 April 2011. ^ "National Museum of Iran". Pbase.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ J. D. Vigne; J. Peters; D. Helmer (2002). First Steps of Animal Domestication, Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology. Oxbow Books, Limited. ISBN 978-1-84217-121-9. ^ Nidhi Subbaraman. "Early humans in Iran were growing wheat 12,000 years ago". NBC News. Retrieved 26 August 2015. ^ "Emergence of Agriculture in the Foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Iran", by Simone Riehl, Mohsen Zeidi, Nicholas J. Conard – University of Tübingen, publication 10 May 2013 ^ "Excavations at Chogha Bonut: The earliest village in Susiana". Oi.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Hole, Frank (20 July 2004). "NEOLITHIC AGE IN IRAN". Encyclopedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012. ^ K. Kris Hirst. "Chogha Mish (Iran)". Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013. ^ Collon, Dominique (1995). Ancient Near Eastern Art. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20307-5. Retrieved 4 July 2013. ^ a b "New evidence: modern civilization began in Iran". News.xinhuanet.com. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ D. T. Potts (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-521-56496-0. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ "Panorama – 03/03/07". Iran Daily. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Iranian.ws, "Archaeologists: Modern civilization began in Iran based on new evidence", 12 August 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007. Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ Whatley, Christopher (2001). Bought and Sold for English Gold: The Union of 1707. Tuckwell Press. ^ Lowell Barrington (2012). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices, 2nd ed.tr: Structures and Choices. Cengage Learning. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-111-34193-0. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ "Ancient Scripts:Elamite". 1996. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011. ^ Basu, Dipak. "Death of the Aryan Invasion Theory". iVarta.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2013. ^ Cory Panshin. "The Palaeolithic Indo-Europeans". Panshin.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Afary, Janet; Peter William Avery; Khosrow Mostofi. "Iran (Ethnic Groups)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 April 2011. ^ a b Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Adult. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7. ^ "Median Empire". Iran Chamber Society. 2001. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011. ^ A. G. Sagona (2006). The Heritage of Eastern Turkey: From Earliest Settlements to Islam. Macmillan Education AU. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-876832-05-6. ^ "Urartu civilization". allaboutturkey.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015. ^ Llewellyn-Jones, L. (2022). Persians: The Age of the Great Kings. Basic Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-5416-0035-5. ^ a b c David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Facts On File. pp. 256 (at the right portion of the page). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1. Retrieved 17 August 2016. ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Encyclopædia Britannica Encyclopedia Article: Media ancient region, Iran". Britannica.com. Retrieved 25 August 2010. ^ Ehsan Yarshater (1996). Encyclopaedia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-56859-028-8. ^ While estimates for the Achaemenid Empire range from 10 to 80+ million, most prefer 50 million. Prevas (2009, p. 14) estimates 10 million. Strauss (2004, p. 37) estimates about 20 million. Ward (2009, p. 16) estimates at 20 million. Scheidel (2009, p. 99) estimates 35 million. Daniel (2001, p. 41) estimates at 50 million. Meyer and Andreades (2004, p. 58) estimates to 50 million. Jones (2004, p. 8) estimates over 50 million. Richard (2008, p. 34) estimates nearly 70 million. Hanson (2001, p. 32) estimates almost 75 million. Cowley (1999 and 2001, p. 17) estimates possibly 80 million. ^ "Largest empire by percentage of world population". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 11 March 2015. ^ "Cyrus the Great". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 November 2018. In the Bible (e.g., Ezra 1:1–4), Cyrus is famous for freeing the Jewish captives in Babylonia and allowing them to return to their homeland. ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Achaemenid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. ^ Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) ^ Roisman & Worthington 2011, pp. 135–138, 342–345. ^ Jakobsson, Jens (2004). "Seleucid Empire". Iran Chamber Society. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011. ^ a b Stillman, Norman A. (1979). The Jews of Arab Lands. Jewish Publication Society. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8276-1155-9. ^ a b Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Haarer, Fiona K. (2006). Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies: London, 21–26 August, 2006, Volume 1. Ashgate Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7546-5740-8. ^ Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta; Stewart, Sarah (2005), Birth of the Persian Empire: The Idea of Iran, London: I.B. Tauris, p. 108, ISBN 978-1-84511-062-8, Similarly the collapse of Sassanian Eranshahr in AD 650 did not end Iranians' national idea. The name 'Iran' disappeared from official records of the Saffarids, Samanids, Buyids, Saljuqs and their successor. But one unofficially used the name Iran, Eranshahr, and similar national designations, particularly Mamalek-e Iran or 'Iranian lands', which exactly translated the old Avestan term Ariyanam Daihunam. On the other hand, when the Safavids (not Reza Shah, as is popularly assumed) revived a national state officially known as Iran, bureaucratic usage in the Ottoman empire and even Iran itself could still refer to it by other descriptive and traditional appellations. ^ Bury, J.B. (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian, Part 1. Courier Corporation. pp. 90–92. ^ Durant, Will (2011). The Age of Faith: The Story of Civilization. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4761-7. Repaying its debt, Sasanian art exported its forms and motives eastward into India, Turkestan, and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt, and Spain. ^ "Transoxiana 04: Sasanians in Africa". Transoxiana.com.ar. Retrieved 16 December 2013. ^ Dutt, Romesh Chunder; Smith, Vincent Arthur; Lane-Poole, Stanley; Elliot, Henry Miers; Hunter, William Wilson; Lyall, Alfred Comyn (1906). History of India. Vol. 2. Grolier Society. p. 243. ^ "Iransaga: The art of Sassanians". Artarena.force9.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2013. ^ George Liska (1998). Expanding Realism: The Historical Dimension of World Politics. Rowman & Littlefield Pub Incorporated. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8476-8680-3. ^ "The Rise and Spread of Islam, The Arab Empire of the Umayyads – Weakness of the Adversary Empires". Occawlonline.pearsoned.com. Retrieved 30 November 2015. ^ Stepaniants, Marietta (2002). "The Encounter of Zoroastrianism with Islam". Philosophy East and West. University of Hawai'i Press. 52 (2): 159–172. doi:10.1353/pew.2002.0030. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 1399963. S2CID 201748179. ^ Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (2 ed.). New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8. ^ Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 878. ISBN 978-0-415-96692-4. ^ "Under Persian rule". BBC. Retrieved 16 December 2009. ^ Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006). The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran (reprint ed.). I.B. Tauris. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-84511-056-7. ^ Kamran Hashemi (2008). Religious Legal Traditions, International Human Rights Law and Muslim States. Brill. p. 142. ISBN 978-90-04-16555-7. ^ Suha Rassam (2005). Iraq: Its Origins and Development to the Present Day. Gracewing Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-85244-633-1. ^ Zarrinkub,'Abd Al-Husain (1975). "The Arab Conquest of Iran and Its Aftermath". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 4. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6. ^ Spuler, Bertold (1994). A History of the Muslim World: The age of the caliphs (Illustrated ed.). Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-55876-095-0. ^ "Islamic History: The Abbasid Dynasty". Religion Facts. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2011. ^ a b Hooker, Richard (1996). "The Abbasid Dynasty". Washington State University. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011. ^ Joel Carmichael (1967). The Shaping of the Arabs. p. 235. ISBN 9780025214200. Retrieved 21 June 2013. Abu Muslim, the Persian general and popular leader ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (1960). Iran (2, revised ed.). G. Allen & Unwin. p. 47. Retrieved 23 June 2013. A Persian Muslim called Abu Muslim. ^ Sayyid Fayyaz Mahmud (1988). A Short History of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-577384-2. ^ "Iraq – History | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 29 June 2022. ^ Paul Kane (2009). "Emerson and Hafiz: The Figure of the Religious Poet". Religion & Literature. 41 (1): 111–139. JSTOR 25676860. ^ Shafiq Shamel. Goethe and Hafiz: Poetry and History in the West-östlicher Diwan. ^ Adineh Khojasteh Pour; Behnam Mirza Baba Zadeh (28 March 2014). Socrates: Vol 2, No 1 (2014): Issue – March – Section 07. The Reception of Classical Persian Poetry in Anglophone World: Problems and Solutions. Retrieved 26 October 2015. ^ Richard G. Hovannisian; Georges Sabagh (1998). The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-59185-0. The Golden age of Islam [...] attributable, in no small measure, to the vital participation of Persian men of letters, philosophers, theologians, grammarians, mathematicians, musicians, astronomers, geographers, and physicians ^ Bernard Lewis (2004). From Babel to Dragomans : Interpreting the Middle East: Interpreting the Middle East. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-803863-4. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ... the Iranian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. ^ Richard Nelson Frye (1975). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ a b c d Gene R. Garthwaite (2008). The Persians. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-4400-1. ^ Sigfried J. de Laet. History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century UNESCO, 1994. ISBN 92-3-102813-8 p. 734 ^ Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire Infobase Publishing, 2009 ISBN 1-4381-1025-1 p. 322 ^ a b c d Steven R. Ward (2009). Immortal: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-58901-587-6. ^ "Iran – The Mongol invasion". Encyclopedia Britannica. ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. ^ Beckingham, C. F. (1972). "The Cambridge history of Iran. Vol. V: The Saljuq and Mongol periods. Edited by J. A. Boyle, pp. Xiii, 762, 16 pl. Cambridge University Press, 1968. £3.75". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 104: 68–69. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0012965X. S2CID 161828080. ^ "Isfahan: Iran's Hidden Jewel". Smithsonianmag.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Spuler, Bertold (1960). The Muslim World. Vol. I The Age of the Caliphs. E.J. Brill. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-685-23328-3. ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2008). World History, Volume I. Cengage Learning. p. 466. ISBN 978-0-495-56902-2. ^ a b Andrew J. Newman (2006). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-667-6. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Why is there such confusion about the origins of this important dynasty, which reasserted Iranian identity and established an independent Iranian state after eight and a half centuries of rule by foreign dynasties? RM Savory, Iran under the Safavids (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1980), p. 3. ^ Thabit Abdullah (12 May 2014). A Short History of Iraq. Taylor & Francis. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-317-86419-6. ^ "Safavid Empire (1501–1722)". BBC Religion. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2011. ^ Savory, R. M. "Safavids". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). ^ Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta; Stewart, Sarah (2005), Birth of the Persian Empire: The Idea of Iran, London: I.B. Tauris, p. 108, ISBN 978-1-84511-062-8, Similarly the collapse of Sassanian Eranshahr in AD 650 did not end Iranians' national idea. The name 'Iran' disappeared from official records of the Saffarids, Samanids, Buyids, Saljuqs and their successor. But one unofficially used the name Iran, Eranshahr, and similar national designations, particularly Mamalek-e Iran or 'Iranian lands', which exactly translated the old Avestan term Ariyanam Daihunam. On the other hand, when the Safavids (not Reza Shah, as is popularly assumed) revived a national state officially known as Iran, bureaucratic usage in the Ottoman empire and even Iran itself could still refer to it by other descriptive and traditional appellations. ^ Juan Eduardo Campo, Encyclopedia of Islam, p.625 ^ Shirin Akiner (2004). The Caspian: Politics, Energy and Security. Taylor & Francis. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-203-64167-5. ^ Hala Mundhir Fattah; Frank Caso (2009). A Brief History of Iraq. Infobase Publishing. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8160-5767-2. ^ a b Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. pp. xv, 284. ISBN 978-0-85772-193-8. ^ a b Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 329–330. ^ a b c Dowling, Timothy C. (2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. pp. 728–730. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6. ^ Encyclopedia of Soviet law By Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge, Gerard Pieter van den Berg, William B. Simons, Page 457 ^ Farrokh, Kaveh. Iran at War: 1500–1988. ISBN 1-78096-221-5 ^ Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3. ^ L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4. ^ Ebel, Robert E.; Menon, Rajan (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1. ^ Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4. ^ Çiçek, Kemal; Kuran, Ercüment (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7. ^ Ernest Meyer, Karl; Blair Brysac; Shareen (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1. ^ Gozalova, Nigar (2023). "Qajar Iran at the centre of British–Russian confrontation in the 1820s". The Maghreb Review. 48 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1353/tmr.2023.0003. ISSN 2754-6772. S2CID 255523192. ^ Deutschmann, Moritz (2013). ""All Rulers are Brothers": Russian Relations with the Iranian Monarchy in the Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 401–413. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.759334. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 24482848. S2CID 143785614. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022. ^ Mansoori, Firooz (2008). "17". Studies in History, Language and Culture of Azerbaijan (in Persian). Tehran: Hazar-e Kerman. p. 245. ISBN 978-600-90271-1-8. ^ a b А. Г. Булатова. Лакцы (XIX — нач. XX вв.). Историко-этнографические очерки. — Махачкала, 2000. ^ "Griboedov not only extended protection to those Caucasian captives who sought to go home but actively promoted the return of even those who did not volunteer. Large numbers of Georgian and Armenian captives had lived in Iran since 1804 or as far back as 1795." Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, Peter; Gershevitch, Ilya; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles. The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press – 1991. p. 339 ^ (in Russian) A. S. Griboyedov. "Записка о переселеніи армянъ изъ Персіи въ наши области" Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека ^ Bournoutian. Armenian People, p. 105 ^ Yeroushalmi, David (2009). The Jews of Iran in the Nineteenth Century: Aspects of History, Community. Brill. p. 327. ISBN 978-90-04-15288-5. ^ Colin Brock, Lila Zia Levers. Aspects of Education in the Middle East and Africa Symposium Books Ltd., 7 mei 2007 ISBN 1-873927-21-5 p. 99 ^ Gingeras, Ryan (2016). Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1908–1922. Oxford University Press, Oxford. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-166358-1. Retrieved 18 June 2016. By January, Ottoman regulars and cavalry detachments associated with the old Hamidiye had seized the towns of Urmia, Khoy, and Salmas. Demonstrations of resistance by local Christians, comprising Armenians, Nestorians, Syriacs, and Assyrians, led Ottoman forces to massacre civilians and torch villages throughout the border region of Iran. ^ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B. Tauris. p. 710. ISBN 978-0-85773-020-6. Retrieved 18 June 2016. 'In retaliation, we killed the Armenians of Khoy, and I gave the order to massacre the Armenians of Maku.' ... Without distorting the facts, one can affirm that the centuries-old Armenian presence in the regions of Urmia, Salmast, Qaradagh, and Maku had been dealt a blow from which it would never recover. ^ Yeghiayan, Vartkes, ed. (1991). British Foreign Office Dossiers on Turkish War Criminals. American Armenian International College. ... Assyrians who were killed in Khoy, some 700 Armenian residents of Khoy were also massacred at the same time, June 1918. ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-1-4128-3592-3. ^ Hinton, Alexander Laban; La Pointe, Thomas; Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2013). Hidden Genocides: Power, Knowledge, Memory. Rutgers University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8135-6164-6. ^ Glenn E. Curtis; Eric Hooglund (2008). Iran: A Country Study. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8444-1187-3. ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (2011). Iran at War: 1500–1988. ISBN 978-1-78096-221-4.[permanent dead link] ^ David S. Sorenson (2013). An Introduction to the Modern Middle East: History, Religion, Political Economy, Politics. Westview Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-8133-4922-0. ^ Iran: Foreign Policy & Government Guide. International Business Publications. 2009. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7397-9354-1.[permanent dead link] ^ T.H. Vail Motter (1952). United States Army in World War II the Middle East Theater the Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia. United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016. ^ Louise Fawcett, "Revisiting the Iranian Crisis of 1946: How Much More Do We Know?" Iranian Studies 47#3 (2014): 379–399. ^ Gary R. Hess, "The Iranian Crisis of 1945–46 and the Cold War." Political Science Quarterly 89#1 (1974): 117–146. online ^ Stephen Kinzer (2011). All the Shah's Men. John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-118-14440-4. Retrieved 21 June 2013. ^ Nikki R. Keddie, Rudolph P Matthee. Iran and the Surrounding World: Interactions in Culture and Cultural Politics University of Washington Press, 2002 p. 366 ^ a b Cordesman, Anthony H. (1999). Iran's Military Forces in Transition: Conventional Threats and Weapons of Mass Destruction. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-275-96529-7. ^ Baraheni, Reza (28 October 1976). "Terror in Iran". The New York Review of Books. ^ Christoffel Coetzee, Salidor (2021). The Eye of the Storm. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 978-1543759501. ^ Elizabeth Shakman Hurd (2009). The Politics of Secularism in International Relations. Princeton University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4008-2801-2. Retrieved 17 August 2016. ^ "Islamic Revolution of 1979". Iranchamber.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ "Islamic Revolution of Iran". Encarta. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2011. ^ Fereydoun Hoveyda, The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution ISBN 0-275-97858-3, Praeger Publishers ^ "Iran". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012. ^ Graham, Robert (1980). Iran: The Illusion of Power. London: St. Martin's Press. pp. 19, 96. ISBN 978-0-312-43588-2. ^ "The Iranian Revolution". Fsmitha.com. 22 March 1963. Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ "BBC On this Day Feb 1 1979". BBC. Retrieved 25 November 2014. ^ Lori A. Johnson; Kathleen Uradnik; Sara Beth Hower (2011). Battleground: Government and Politics [2 volumes]: Government and Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-313-34314-8. ^ Jahangir Amuzegar (1991). The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution: The Pahlavis' Triumph and Tragedy. SUNY Press. pp. 4, 9–12. ISBN 978-0-7914-9483-7. ^ Cheryl Benard (1984). "The Government of God": Iran's Islamic Republic. Columbia University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-231-05376-1. ^ "American Experience, Jimmy Carter, "444 Days: America Reacts"". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ Hiro, Dilip (1991). The Longest War: The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict. New York: Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-415-90406-3. OCLC 22347651. ^ Abrahamian, Ervand (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–175, 212. ISBN 978-0-521-52891-7. OCLC 171111098. ^ Dan De Luce in Tehran (4 May 2004). "Khatami blames clerics for failure". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 August 2010. ^ "Iran hardliner becomes president". BBC. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2006. ^ نتایج نهایی دهمین دورهٔ انتخابات ریاست جمهوری (in Persian). Ministry of Interior of Iran. 13 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2009. ^ Ian Black (13 June 2009). "Ahmadinejad wins surprise Iran landslide victory". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2015. ^ "Iran clerics defy election ruling". BBC News. 5 July 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ "Is this government legitimate?". BBC. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ Landry, Carole (25 June 2009). "G8 calls on Iran to halt election violence". Retrieved 18 June 2011. ^ Tait, Robert; Black, Ian; Tran, Mark (17 June 2009). "Iran protests: Fifth day of unrest as regime cracks down on critics". The Guardian. London. ^ "Hassan Rouhani wins Iran presidential election". BBC News. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013. ^ Fassihi, Farnaz (15 June 2013). "Moderate Candidate Wins Iran's Presidential Vote". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 June 2013. ^ Denmark, Abraham M.; Tanner, Travis (2013). Strategic Asia 2013–14: Asia in the Second Nuclear Age. p. 229. ^ Erdbrink, Thomas (4 August 2018). "Protests Pop Up Across Iran, Fueled by Daily Dissatisfaction". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2022. ^ "More Chants, More Protests: The Dey Iranian Anti-Regime Protests". Critical Threats. Retrieved 5 August 2022. ^ "Iran arrested 7,000 in crackdown on dissent during 2018 – Amnesty". BBC News. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2022. ^ "In Pictures: Iranians protest against the increase in fuel prices". Al-Jazeera. 17 November 2019. ^ Shutdown, Iran Internet. "A web of impunity: The killings Iran's internet shutdown hid — Amnesty International". ^ "Special Report: Iran's leader ordered crackdown on unrest – 'Do whatever it takes to end it'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019. ^ Carolien Roelants, Iran expert of NRC Handelsblad, in a debate on Buitenhof on Dutch television, 5 January 2020. ^ "Ukrainian airplane with 180 aboard crashes in Iran: Fars". Reuters. 8 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020. ^ "Demands for justice after Iran's plane admission". BBC. BBC. 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020. ^ "Protests flare across Iran in violent unrest over woman's death". Reuters. 20 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022. ^ Strzyżyńska, Weronika (16 September 2022). "Iranian woman dies 'after being beaten by morality police' over hijab law". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022. ^ Leonhardt, David (26 September 2022). "Iran's Ferocious Dissent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- Stay safeStay safeRead less

WARNING: Iran treats drug offences extremely severely. The death penalty is statutory for those convicted of trafficking or manufacturing of any drug and following a third conviction for drug possession.

Government travel advisories(Information last updated 22 Aug 2019)Canada New Zealand

WARNING: Iran treats drug offences extremely severely. The death penalty is statutory for those convicted of trafficking or manufacturing of any drug and following a third conviction for drug possession.

Government travel advisories(Information last updated 22 Aug 2019)Canada New ZealandIran is still a relatively low-crime country, although thefts and muggings occur. Keep your wits about you, and take the usual precautions against pickpockets in crowded bazaars and buses.

Although its strict Islamic moral code is well known, Iranian laws are not as strict as those of Saudi Arabia. Respecting the dozens of unspoken rules and regulations of Iranian life can be a daunting prospect for travellers, but don't be intimidated. As a foreigner you will be given leeway and it doesn't take long to acclimatise yourself.

Perceptions of outsidersEven though travellers may arrive with the image of a throng chanting "Death to America", the chances of Westerners facing anti-Western sentiment as a traveller are slim. Even hardline Iranians make a clear distinction between the Western governments they distrust and individual travellers who visit their country. Americans may receive the odd jibe about their government's policies, but usually nothing more serious than that. However, it is always best to err on the side of caution and avoid politically-oriented conversations, particularly in taxi cabs. In addition, a few Iranian-Americans have been detained and accused of espionage, as were three American hikers in 2009 who allegedly strayed across into Iran from Iraqi Kurdistan. These kind of incidents are rare, but still the broader implications are worth considering and bearing in mind.

Photography The best time for photography in Iran is during festivals, like Mourning of Muharram.

The best time for photography in Iran is during festivals, like Mourning of Muharram.There are a lot of military and other sensitive facilities in Iran. Photography near military and other government installations is strictly prohibited. Any transgression may result in detention and serious criminal charges, including espionage, which can carry the death penalty. Do not photograph any military object, jails, harbours, or telecommunication devices, airports or other objects and facilities which you suspect are military in nature. Be aware that this rule is taken very seriously in Iran.

WomenFemale travellers should not encounter any major problems when visiting Iran, as long as they obey the local laws – including those on dressing. You will undoubtedly be the subject of at least some unwanted attention.

If you are married to an Iranian, you are subject to Iranian marital laws: you cannot leave the country unless your (former) husband approves. Divorces that have taken place in other countries are not recognised by Iran.

LGBT travellersIranian dual citizens WARNING: Iran is a very dangerous destination for gay and lesbian travellers. Iran is one of the few countries in the world that enforces the death penalty against those involved in LGBT activities. The cultural, societal, and legal abhorrence against the LGBT community is well-documented, and some Iranians consider it morally justified to murder/torture gays and lesbians.

WARNING: Iran is a very dangerous destination for gay and lesbian travellers. Iran is one of the few countries in the world that enforces the death penalty against those involved in LGBT activities. The cultural, societal, and legal abhorrence against the LGBT community is well-documented, and some Iranians consider it morally justified to murder/torture gays and lesbians.If you are regarded Iranian – such as because of dual citizenship, having an Iranian father or being married to an Iranian – your foreign nationality will be ignored by the authorities. If you are arrested, your embassy is not contacted and has little ability to help.

EmergenciesEmergency services are extensive in Iran, and response times are very good compared to other local regions.

Local police control centre, ☏ 110. it is probably easiest to phone 110, as the local police have direct contact with other emergency services, and will probably be the only number with English-speaking operators.Other emergency services are also available.

Ambulance, ☏ 115. Fire and Rescue team, ☏ 125. these numbers are frequently answered by the Ambulance or Fire crew operating from them, there is little guarantee these men will speak English. Rescue and Relief Hotline of the Iranian Red Crescent Society, ☏ 112. Road status information, ☏ 141.Natural disasters EarthquakesBecause of Iran's highly mountainous geography, Iran is prone to earthquakes. 90% of the country is situated on major fault lines, which means that earthquakes occur regularly.

Do not despair though; most of these earthquakes have magnitudes less than 4. Anything greater than 4 is a cause of concern.

The Iranian Seismological Centre maintains a seismic map that is updated every 24 hours. The Iranian Seismological Centre maintains a detailed record of all the earthquakes that have happened. You can look at it here.Other safety issuesIn particular, the tourist centre of Isfahan has had problems with muggings of foreigners in unlicensed taxis, and fake police making random checks of tourists' passports. Only use official taxis, and never allow 'officials' to make impromptu searches of your belongings.

Iranian traffic is congested and chaotic. Guidelines are lax and rarely followed. Pedestrians are advised to exercise caution when crossing the roads, and even greater care when driving on them - Iranian drivers tend to overtake along pavements and any section of the road where there is space. In general, it is not recommended for inexperienced foreigners to drive in Iran. Watch out for joobs (جوب), the open storm water drains that shoulder every road and are easy to miss when walking in the dark.

Travellers should avoid the southeastern area of Iran, particularly the province of Sistan va Baluchistan. The drug trade thrives based on smuggling heroin from Afghanistan. There is plenty of associated robbery, kidnapping and murder. Some cities, such as Zahedan, Zabol and Mirjaveh are particularly dangerous, although not every place in this region is dangerous. Chahbahar, which is close to the Pakistani border, is a very calm and friendly city.