Magyarország

HungaryContext of Hungary

Hungary (Hungarian: Magyarország [ˈmɒɟɒrorsaːɡ] (listen)) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning 93,030 square kilometres (35,920 sq mi) of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and Slovenia to the southwest, and Austria to the west. Hungary has a population of 9.7 million, mostly ethnic Hungarians and a significant Romani minority. Hungarian, the official language, is the world's most widely spoken Uralic language and among the few non-Indo-European languages widely spoken in Europe. Budapest is the country's capital and largest city; other major urban areas include Debrecen, Szeged, Miskolc, Pécs, and Győr.

The territory of present-day Hungary has for centuries been a crossroads for various peoples, including C...Read more

Hungary (Hungarian: Magyarország [ˈmɒɟɒrorsaːɡ] (listen)) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning 93,030 square kilometres (35,920 sq mi) of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and Slovenia to the southwest, and Austria to the west. Hungary has a population of 9.7 million, mostly ethnic Hungarians and a significant Romani minority. Hungarian, the official language, is the world's most widely spoken Uralic language and among the few non-Indo-European languages widely spoken in Europe. Budapest is the country's capital and largest city; other major urban areas include Debrecen, Szeged, Miskolc, Pécs, and Győr.

The territory of present-day Hungary has for centuries been a crossroads for various peoples, including Celts, Romans, Germanic tribes, Huns, West Slavs and the Avars. The foundation of the Hungarian state was established in the late 9th century AD with the conquest of the Carpathian Basin by Hungarian grand prince Árpád. His great-grandson Stephen I ascended the throne in 1000, converting his realm to a Christian kingdom. By the 12th century, Hungary became a regional power, reaching its cultural and political height in the 15th century. Following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, it was partially occupied by the Ottoman Empire (1541–1699). Hungary came under Habsburg rule at the turn of the 18th century, later joining with the Austrian Empire to form Austria-Hungary, a major power into the early 20th century.

Austria-Hungary collapsed after World War I, and the subsequent Treaty of Trianon established Hungary's current borders, resulting in the loss of 71% of its territory, 58% of its population, and 32% of ethnic Hungarians. Following the tumultuous interwar period, Hungary joined the Axis powers in World War II, suffering significant damage and casualties. Postwar Hungary became a satellite state of the Soviet Union, leading to the establishment of the Hungarian People's Republic. Following the failed 1956 revolution, Hungary became a comparatively freer, though still repressed, member of the Eastern Bloc. The removal of Hungary's border fence with Austria accelerated the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and subsequently the Soviet Union. On 23 October 1989, Hungary again became a democratic parliamentary republic. Hungary joined the European Union in 2004 and has been part of the Schengen Area since 2007.

Hungary is a middle power in international affairs, owing mostly to its cultural and economic influence. It is a high-income economy with universal health care and tuition-free secondary education. Hungary has a long history of significant contributions to arts, music, literature, sports, science and technology. It is a popular tourist destination in Europe, drawing 24.5 million international tourists in 2019. It is a member of numerous international organisations, including the Council of Europe, NATO, United Nations, World Health Organization, World Trade Organization, World Bank, International Investment Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the Visegrád Group.

More about Hungary

- Currency Hungarian forint

- Native name Magyarország

- Calling code +36

- Internet domain .hu

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 6.5

- Population 9599744

- Area 93036

- Driving side right

- Before 895

Read moreBefore 895Read less

Read moreBefore 895Read less Roman provinces: Illyricum, Macedonia, Dacia, Moesia, Pannonia, Thracia

Roman provinces: Illyricum, Macedonia, Dacia, Moesia, Pannonia, ThraciaThe Roman Empire conquered the territory between the Alps and the area west of the Danube River from 16 to 15 BC, the Danube being the frontier of the empire.[1] In 14 BC, Pannonia, the western part of the Carpathian Basin, which includes today's west of Hungary, was recognised by emperor Augustus in the Res Gestae Divi Augusti as part of the Roman Empire.[1] The area south-east of Pannonia was organised as the Roman province Moesia in 6 BC.[1] An area east of the river Tisza became the Roman province of Dacia in 106 AD, which included today's east Hungary. It remained under Roman rule until 271.[2] From 235, the Roman Empire went through troubled times, caused by revolts, rivalry and rapid succession of emperors. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century under the stress of the migration of Germanic tribes and Carpian pressure.[2]

This period brought many invaders into Central Europe, beginning with the Hunnic Empire (c. 370–469). The most powerful ruler of the Hunnic Empire was Attila the Hun (434–453), who later became a central figure in Hungarian mythology.[3] After the disintegration of the Hunnic Empire, the Gepids, an Eastern Germanic tribe, who had been vassalised by the Huns, established their own kingdom in the Carpathian Basin.[4] Other groups which reached the Carpathian Basin during the Migration Period were the Goths, Vandals, Lombards, and Slavs.[2]

In the 560s, the Avars founded the Avar Khaganate, a state that maintained supremacy in the region for more than two centuries. The Franks under Charlemagne defeated the Avars in a series of campaigns during the 790s.[5] Between 804 and 829, the First Bulgarian Empire conquered the lands east of the Danube and took over the rule of the local Slavic tribes and remnants of the Avars.[6] By the mid-9th century, the Balaton Principality, also known as Lower Pannonia, was established west of the Danube as part of the Frankish March of Pannonia.[7]

Middle Ages (895–1526) Hungarian raids in the 10th century

Hungarian raids in the 10th centuryThe freshly unified Hungarians[8] led by Árpád (by tradition a descendant of Attila), settled in the Carpathian Basin starting in 895.[9][10] According to the Finno-Ugrian theory, they originated from an ancient Uralic-speaking population that formerly inhabited the forested area between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.[11] As a federation of united tribes, Hungary was established in 895, some 50 years after the division of the Carolingian Empire at the Treaty of Verdun in 843, before the unification of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Initially, the rising Principality of Hungary ("Western Tourkia" in medieval Greek sources)[12] was a state created by a semi-nomadic people. It accomplished an enormous transformation into a Christian realm during the 10th century.[13] This state was well-functioning, and the nation's military power allowed the Hungarians to conduct successful fierce campaigns and raids, from Constantinople to as far as today's Spain.[13] The Hungarians defeated three major East Frankish imperial armies between 907 and 910.[14] A defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 signaled a provisory end to most campaigns on foreign territories, at least towards the west.

Age of Árpádian kings King Saint Stephen, the first King of Hungary, converted the nation to Christianity.

King Saint Stephen, the first King of Hungary, converted the nation to Christianity.In 972, the ruling prince (Hungarian: fejedelem) Géza of the Árpád dynasty officially started to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe.[15] His first-born son, Saint Stephen I, became the first King of Hungary after defeating his pagan uncle Koppány, who also claimed the throne. Under Stephen, Hungary was recognised as a Catholic Apostolic Kingdom.[16] Applying to Pope Sylvester II, Stephen received the insignia of royalty (including probably a part of the Holy Crown of Hungary, currently kept in the Hungarian Parliament) from the papacy.

By 1006, Stephen consolidated his power and started sweeping reforms to convert Hungary into a Western feudal state. The country switched to using Latin for administration purposes, and until as late as 1844, Latin remained the official language of administration. Around this time, Hungary began to become a powerful kingdom.[citation needed] Ladislaus I extended Hungary's frontier in Transylvania and invaded Croatia in 1091.[17][18][19][20] The Croatian campaign culminated in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain in 1097 and a personal union of Croatia and Hungary in 1102, ruled by Coloman.[21]

The Holy Crown (Szent Korona), one of the key symbols of Hungary

The Holy Crown (Szent Korona), one of the key symbols of HungaryThe most powerful and wealthiest king of the Árpád dynasty was Béla III, who disposed of the equivalent of 23 tonnes of silver per year, according to a contemporary income register. This exceeded the income of the French king (estimated at 17 tonnes) and was double the receipts of the English Crown.[22] Andrew II issued the Diploma Andreanum which secured the special privileges of the Transylvanian Saxons and is considered the first autonomy law in the world.[23] He led the Fifth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1217, setting up the largest royal army in the history of Crusades. His Golden Bull of 1222 was the first constitution in Continental Europe. The lesser nobles also began to present Andrew with grievances, a practice that evolved into the institution of the parliament (parlamentum publicum).

In 1241–1242, the kingdom received a major blow with the Mongol (Tatar) invasion. Up to half of Hungary's population of 2 million were victims of the invasion.[24] King Béla IV let Cumans and Jassic people into the country, who were fleeing the Mongols.[25] Over the centuries, they were fully assimilated into the Hungarian population.[26] After the Mongols retreated, King Béla ordered the construction of hundreds of stone castles and fortifications, to defend against a possible second Mongol invasion. The Mongols returned to Hungary in 1285, but the newly built stone-castle systems and new tactics (using a higher proportion of heavily armed knights) stopped them. The invading Mongol force was defeated[27] near Pest by the royal army of King Ladislaus IV. As with later invasions, it was repelled handily, the Mongols losing much of their invading force.

Age of elected kings A map of the lands ruled by Louis the Great in Pallas's Great Encyclopedia

A map of the lands ruled by Louis the Great in Pallas's Great EncyclopediaThe Kingdom of Hungary reached one of its greatest extents during the Árpádian kings, yet royal power was weakened at the end of their rule in 1301. After a destructive period of interregnum (1301–1308), the first Angevin king, Charles I of Hungary – a bilineal descendant of the Árpád dynasty – successfully restored royal power and defeated oligarch rivals, the so-called "little kings". The second Angevin Hungarian king, Louis the Great (1342–1382), led many successful military campaigns from Lithuania to southern Italy (Kingdom of Naples) and was also King of Poland from 1370. After King Louis died without a male heir, the country was stabilised only when Sigismund of Luxembourg (1387–1437) succeeded to the throne, who in 1433 also became Holy Roman Emperor. Sigismund was also (in several ways) a bilineal descendant of the Árpád dynasty.

Map of the lands ruled by Matthias Corvinus. Designed by Dr. Lajos Baróti.

Map of the lands ruled by Matthias Corvinus. Designed by Dr. Lajos Baróti.The first Hungarian Bible translation was completed in 1439. For half a year in 1437, there was an antifeudal and anticlerical peasant revolt in Transylvania which was strongly influenced by Hussite ideas.

From a small noble family in Transylvania, John Hunyadi grew to become one of the country's most powerful lords, thanks to his outstanding capabilities as a mercenary commander. He was elected governor, then regent. He was a successful crusader against the Ottoman Turks, one of his greatest victories being the siege of Belgrade in 1456.

The last strong king of medieval Hungary was the Renaissance king Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490), son of John Hunyadi. His election was the first time that a member of the nobility mounted to the Hungarian royal throne without dynastic background. He was a successful military leader and an enlightened patron of the arts and learning.[28] His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's greatest collection of historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century, and second only in size to the Vatican Library. Items from the Bibliotheca Corviniana were inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2005.[29] The serfs and common people considered him a just ruler because he protected them from excessive demands and other abuses by the magnates.[30] Under his rule, in 1479, the Hungarian army destroyed the Ottoman and Wallachian troops at the Battle of Breadfield. Abroad he defeated the Polish and German imperial armies of Frederick at Breslau (Wrocław). Matthias' mercenary standing army, the Black Army of Hungary, was an unusually large army for its time, and it conquered Vienna as well as parts of Austria and Bohemia.

Decline (1490–1526)King Matthias died without lawful sons, and the Hungarian magnates procured the accession of the Pole Vladislaus II (1490–1516), supposedly because of his weak influence on Hungarian aristocracy.[28] Hungary's international role declined, its political stability was shaken, and social progress was deadlocked.[31] In 1514, the weakened old King Vladislaus II faced a major peasant rebellion led by György Dózsa, which was ruthlessly crushed by the nobles, led by John Zápolya. The resulting degradation of order paved the way for Ottoman pre-eminence. In 1521, the strongest Hungarian fortress in the South, Nándorfehérvár (today's Belgrade, Serbia), fell to the Turks. The early appearance of Protestantism further worsened internal relations in the country.

Ottoman wars (1526–1699) Painting commemorating the siege of Eger, a major victory against the Ottomans

Painting commemorating the siege of Eger, a major victory against the OttomansAfter some 150 years of wars with the Hungarians and other states, the Ottomans gained a decisive victory over the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, where King Louis II died while fleeing. Amid political chaos, the divided Hungarian nobility elected two kings simultaneously, John Zápolya and Ferdinand I of the Habsburg dynasty. With the conquest of Buda by the Turks in 1541, Hungary was divided into three parts and remained so until the end of the 17th century. The north-western part, termed as Royal Hungary, was annexed by the Habsburgs who ruled as kings of Hungary. The eastern part of the kingdom became independent as the Principality of Transylvania, under Ottoman (and later Habsburg) suzerainty. The remaining central area, including the capital Buda, was known as the Pashalik of Buda.

The vast majority of the seventeen and nineteen thousand Ottoman soldiers in service in the Ottoman fortresses in the territory of Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs rather than ethnic Turkish people.[32] Orthodox Southern Slavs were also acting as akinjis and other light troops intended for pillaging in the territory of present-day Hungary.[33] In 1686, the Holy League's army, containing over 74,000 men from various nations, reconquered Buda from the Turks. After some more crushing defeats of the Ottomans in the next few years, the entire Kingdom of Hungary was removed from Ottoman rule by 1718. The last raid into Hungary by the Ottoman vassals Tatars from Crimea took place in 1717.[34] The constrained Habsburg Counter-Reformation efforts in the 17th century reconverted the majority of the kingdom to Catholicism. The ethnic composition of Hungary was fundamentally changed as a consequence of the prolonged warfare with the Turks. A large part of the country became devastated, population growth was stunted, and many smaller settlements perished.[35] The Austrian-Habsburg government settled large groups of Serbs and other Slavs in the depopulated south, and settled Germans (called Danube Swabians) in various areas, but Hungarians were not allowed to settle or re-settle in the south of the Carpathian Basin.[36]

From the 18th century to World War I (1699–1918) Francis II Rákóczi, leader of the war of independence against Habsburg rule in 1703–11

Francis II Rákóczi, leader of the war of independence against Habsburg rule in 1703–11 Count István Széchenyi offered one year's income to establish the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Count István Széchenyi offered one year's income to establish the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The siege of Buda in May 1849

The siege of Buda in May 1849 Ethnic and political situation in the Kingdom of Hungary according to the 1910 census

Ethnic and political situation in the Kingdom of Hungary according to the 1910 census Lajos Kossuth, Regent-President during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848

Lajos Kossuth, Regent-President during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen consisted of the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary (16) and the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (17).

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen consisted of the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary (16) and the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (17).Between 1703 and 1711, there was a large-scale war of independence led by Francis II Rákóczi, who after the dethronement of the Habsburgs in 1707 at the Diet of Ónod, took power provisionally as the ruling prince for the wartime period, but refused the Hungarian crown and the title "king". The uprisings lasted for years. The Hungarian Kuruc army, although taking over most of the country, lost the main battle at Trencsén (1708). Three years later, because of the growing desertion, defeatism, and low morale, the Kuruc forces finally surrendered.[37]

During the Napoleonic Wars and afterward, the Hungarian Diet had not convened for decades.[38] In the 1820s, the emperor was forced to convene the Diet, which marked the beginning of a Reform Period (1825–1848, Hungarian: reformkor). Count István Széchenyi, one of the most prominent statesmen of the country, recognised the urgent need for modernisation and his message got through. The Hungarian Parliament was reconvened in 1825 to handle financial needs. A liberal party emerged and focused on providing for the peasantry. Lajos Kossuth—a famous journalist at that time—emerged as a leader of the lower gentry in the Parliament. A remarkable upswing started as the nation concentrated its forces on modernisation even though the Habsburg monarchs obstructed all important liberal laws relating to civil and political rights and economic reforms. Many reformers (Lajos Kossuth, Mihály Táncsics) were imprisoned by the authorities.

On 15 March 1848, mass demonstrations in Pest and Buda enabled Hungarian reformists to push through a list of 12 demands. Under Governor and President Lajos Kossuth and Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány, the House of Habsburg was dethroned. The Habsburg ruler and his advisors skillfully manipulated the Croatian, Serbian and Romanian peasantry, led by priests and officers firmly loyal to the Habsburgs, and induced them to rebel against the Hungarian government, though the Hungarians were supported by the vast majority of the Slovak, German and Rusyn nationalities and by all the Jews of the kingdom, as well as by a large number of Polish, Austrian and Italian volunteers.[39] In July 1849 the Hungarian Parliament proclaimed and enacted the first laws of ethnic and minority rights in the world.[40] Many members of the nationalities gained the coveted highest positions within the Hungarian Army, like General János Damjanich, an ethnic Serb who became a Hungarian national hero through his command of the 3rd Hungarian Army Corps or Józef Bem, who was Polish and also became a national hero in Hungary. The Hungarian forces (Honvédség) defeated Austrian armies. To counter the successes of the Hungarian revolutionary army, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph I asked for help from the "Gendarme of Europe", Tsar Nicholas I, whose Russian armies invaded Hungary. This made Artúr Görgey surrender in August 1849. The leader of the Austrian army, Julius Jacob von Haynau, became governor of Hungary for a few months and ordered the execution of the 13 Martyrs of Arad, leaders of the Hungarian army, and Prime Minister Batthyány in October 1849. Kossuth escaped into exile. Following the war of 1848–1849, the whole country was in "passive resistance".

Coronation of Francis Joseph I and Elisabeth Amalie at Matthias Church, Buda, 8 June 1867

Coronation of Francis Joseph I and Elisabeth Amalie at Matthias Church, Buda, 8 June 1867Because of external and internal problems, reforms seemed inevitable, and major military defeats of Austria forced the Habsburgs to negotiate the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, by which the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was formed. This empire had the second largest area in Europe (after the Russian Empire), and it was the third most populous (after Russia and the German Empire). The two realms were governed separately by two parliaments from two capital cities, with a common monarch and common external and military policies. Economically, the empire was a customs union. The old Hungarian Constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph I was crowned as King of Hungary. The era witnessed impressive economic development. The formerly backward Hungarian economy became relatively modern and industrialised by the turn of the 20th century, although agriculture remained dominant until 1890. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda were officially united with Pest,[41] thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period.

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Prime Minister István Tisza and his cabinet tried to avoid the outbreak and escalating of a war in Europe, but their diplomatic efforts were unsuccessful. Austria-Hungary drafted 9 million (fighting forces: 7.8 million) soldiers in World War I (over 4 million from the Kingdom of Hungary) on the side of Germany, Bulgaria, and Turkey. The troops raised in the Kingdom of Hungary spent little time defending the actual territory of Hungary, with the exceptions of the Brusilov offensive in June 1916 and a few months later when the Romanian army made an attack into Transylvania,[42][self-published source?] both of which were repelled. The Central Powers conquered Serbia. Romania declared war. The Central Powers conquered southern Romania and the Romanian capital Bucharest. In 1916 Emperor Joseph died, and the new monarch Charles IV sympathised with the pacifists. With great difficulty, the Central Powers stopped and repelled the attacks of the Russian Empire.

The Eastern Front of the Allied (Entente) Powers completely collapsed. The Austro-Hungarian Empire then withdrew from all defeated countries. On the Italian front, the Austro-Hungarian army made no progress against Italy after January 1918. Despite great success on the Eastern Front, Germany suffered complete defeat on the Western Front. By 1918, the economic situation had deteriorated (strikes in factories were organised by leftist and pacifist movements) and uprisings in the army had become commonplace. In the capital cities, the Austrian and Hungarian leftist liberal movements (the maverick parties) and their leaders supported the separatism of ethnic minorities. Austria-Hungary signed a general armistice in Padua on 3 November 1918.[43] In October 1918, Hungary's union with Austria was dissolved.

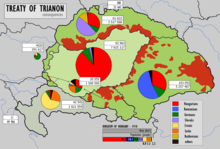

Between the World Wars (1918–1941) With the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost 72% of its territory, its sea ports, and 3,425,000 ethnic Hungarians[44][45]Majority Hungarian areas (according to the 1910 census) detached from Hungary

With the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost 72% of its territory, its sea ports, and 3,425,000 ethnic Hungarians[44][45]Majority Hungarian areas (according to the 1910 census) detached from HungaryFollowing the First World War, Hungary underwent a period of profound political upheaval, beginning with the Aster Revolution in 1918, which brought the social-democratic Mihály Károlyi to power as prime minister. The Hungarian Royal Honvéd army still had more than 1,400,000 soldiers[46][47] when Károlyi was installed. Károlyi yielded to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's demand for pacifism by ordering the disarmament of the Hungarian army. This happened under the direction of Béla Linder, minister of war in the Károlyi government.[48][49] Disarmament of its army meant that Hungary was to remain without a national defence at a time of particular vulnerability. During the rule of Károlyi's pacifist cabinet, Hungary lost control over approximately 75% of its former pre-WW1 territories (325,411 square kilometres (125,642 sq mi)) without a fight and was subject to foreign occupation. The Little Entente, sensing an opportunity, invaded the country from three sides—Romania invaded Transylvania, Czechoslovakia annexed Upper Hungary (today's Slovakia), and a joint Serb-French coalition annexed Vojvodina and other southern regions. In March 1919, communists led by Béla Kun ousted the Károlyi government and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic (Tanácsköztársaság), followed by a thorough Red Terror campaign. Despite some successes on the Czechoslovak front, Kun's forces were ultimately unable to resist the Romanian invasion; by August 1919, Romanian troops occupied Budapest and ousted Kun.

Miklós Horthy, Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1944)

Miklós Horthy, Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1944)In November 1919, rightist forces led by former Austro-Hungarian admiral Miklós Horthy entered Budapest; exhausted by the war and its aftermath, the populace accepted Horthy's leadership. In January 1920, parliamentary elections were held, and Horthy was proclaimed regent of the reestablished Kingdom of Hungary, inaugurating the so-called "Horthy era" (Horthy-kor). The new government worked quickly to normalise foreign relations while turning a blind eye to a White Terror that swept through the countryside; extrajudicial killings of suspected communists and Jews lasted well into 1920. On 4 June 1920, the Treaty of Trianon established new borders for Hungary. The country lost 71% of its territory and 66% of its pre-war population, as well as many sources of raw materials and its sole port at Fiume.[50][51] Though the revision of the treaty quickly rose to the top of the national political agenda, the Horthy government was not willing to resort to military intervention to do so.

The initial years of the Horthy regime were preoccupied with putsch attempts by Charles IV, the Austro-Hungarian pretender; continued suppression of communists; and a migration crisis triggered by the Trianon territorial changes. Though free elections continued, Horthy's personality and those of his personally selected prime ministers dominated the political scene. The government's actions continued to drift right with the passage of antisemitic laws and, because of the continued isolation of the Little Entente, economic and then political gravitation towards Italy and Germany. The Great Depression further exacerbated the situation, and the popularity of fascist politicians increased, such as Gyula Gömbös and Ferenc Szálasi, promising economic and social recovery.

Horthy's nationalist agenda reached its apogee in 1938 and 1940, when the Nazis rewarded Hungary's staunchly pro-Germany foreign policy in the First and Second Vienna Awards, peacefully restoring ethnic-Hungarian-majority areas lost after Trianon. In 1939, Hungary regained further territory from Czechoslovakia through force. Hungary formally joined the Axis powers on 20 November 1940 and in 1941 participated in the invasion of Yugoslavia, gaining some of its former territories in the south.

World War II (1941–1945) Kingdom of Hungary, 1941–44

Kingdom of Hungary, 1941–44Hungary formally entered World War II as an Axis power on 26 June 1941, declaring war on the Soviet Union after unidentified planes bombed Kassa, Munkács, and Rahó. Hungarian troops fought on the Eastern Front for two years. Despite early success at the Battle of Uman,[52] the government began seeking a secret peace pact with the Allies after the Second Army suffered catastrophic losses at the River Don in January 1943. Learning of the planned defection, German troops occupied Hungary on 19 March 1944 to guarantee Horthy's compliance. In October, as the Soviet front approached, and the government made further efforts to disengage from the war, German troops ousted Horthy and installed a puppet government under Szálasi's fascist Arrow Cross Party.[52] Szálasi pledged all the country's capabilities in service of the German war machine. By October 1944, the Soviets had reached the river Tisza, and despite some losses, succeeded in encircling and besieging Budapest in December.

Jewish women being arrested on Wesselényi Street in Budapest during the Holocaust, c. 20–22 October 1944

Jewish women being arrested on Wesselényi Street in Budapest during the Holocaust, c. 20–22 October 1944After German occupation, Hungary participated in the Holocaust.[53][54] During the German occupation in May–June 1944, the Arrow Cross and Hungarian police deported nearly 440,000 Jews, mainly to Auschwitz. Nearly all of them were murdered.[55][56] The Swedish Diplomat Raoul Wallenberg managed to save a considerable number of Hungarian Jews by giving them Swedish passports.[57] Rezső Kasztner, one of the leaders of the Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee, bribed senior SS officers such as Adolf Eichmann to allow some Jews to escape.[58][59][60] The Horthy government's complicity in the Holocaust remains a point of controversy and contention.

The war left Hungary devastated, destroying over 60% of the economy and causing significant loss of life. In addition to the over 600,000 Hungarian Jews killed,[61] as many as 280,000[62][63] other Hungarians were raped, murdered and executed or deported for slave labour by Czechoslovaks,[64][65][66][67][68][69] Soviet Red Army troops,[70][71][72] and Yugoslavs.[73]

On 13 February 1945, Budapest surrendered; by April, German troops left the country under Soviet military occupation. 200,000 Hungarians were expelled from Czechoslovakia in exchange for 70,000 Slovaks living in Hungary. 202,000 ethnic Germans were expelled to Germany,[74] and through the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties, Hungary was again reduced to its immediate post-Trianon borders.

Communism (1945–1989)Following the defeat of Nazi Germany, Hungary became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. The Soviet leadership selected Mátyás Rákosi to front the Stalinisation of the country, and Rákosi de facto ruled Hungary from 1949 to 1956. His government's policies of militarisation, industrialisation, collectivisation, and war compensation led to a severe decline in living standards. In imitation of Stalin's KGB, the Rákosi government established a secret political police, the ÁVH, to enforce the regime. In the ensuing purges, approximately 350,000 officials and intellectuals were imprisoned or executed from 1948 to 1956.[75] Many freethinkers, democrats, and Horthy-era dignitaries were secretly arrested and extrajudicially interned in domestic and foreign gulags. Some 600,000 Hungarians were deported to Soviet labour camps, where at least 200,000 died.[76]

A destroyed Soviet tank in Budapest during the Revolution of 1956. Time's Man of the Year for 1956 was the Hungarian freedom fighter.[77]

A destroyed Soviet tank in Budapest during the Revolution of 1956. Time's Man of the Year for 1956 was the Hungarian freedom fighter.[77]After Stalin's death in 1953, the Soviet Union pursued a programme of de-Stalinisation that was inimical to Rákosi, leading to his deposition. The following political cooling saw the ascent of Imre Nagy to the premiership and the growing interest of students and intellectuals in political life. Nagy promised market liberalisation and political openness, while Rákosi opposed both vigorously. Rákosi eventually managed to discredit Nagy and replace him with the more hard-line Ernő Gerő. Hungary joined the Warsaw Pact in May 1955, as societal dissatisfaction with the regime swelled. Following the firing on peaceful demonstrations by Soviet soldiers and secret police, and rallies throughout the country on 23 October 1956, protesters took to the streets in Budapest, initiating the 1956 Revolution. In an effort to quell the chaos, Nagy returned as premier, promised free elections, and took Hungary out of the Warsaw Pact.

The violence nonetheless continued as revolutionary militias sprung up against the Soviet Army and the ÁVH; the roughly 3,000-strong resistance fought Soviet tanks using Molotov cocktails and machine-pistols. Though the preponderance of the Soviets was immense, they suffered heavy losses, and by 30 October 1956, most Soviet troops had withdrawn from Budapest to garrison the countryside. For a time, the Soviet leadership was unsure how to respond but eventually decided to intervene to prevent a destabilisation of the Soviet bloc. On 4 November, reinforcements of more than 150,000 troops and 2,500 tanks entered the country from the Soviet Union.[78] Nearly 20,000 Hungarians were killed resisting the intervention, while an additional 21,600 were imprisoned afterward for political reasons. Some 13,000 were interned and 230 brought to trial and executed. Nagy was secretly tried, found guilty, sentenced to death, and executed by hanging in June 1958. Because borders were briefly opened, nearly a quarter of a million people fled the country by the time the revolution was suppressed.[79]

Kádár era (1956–1988) János Kádár, General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (1956–1988)

János Kádár, General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (1956–1988)After a second, briefer period of Soviet military occupation, János Kádár, Nagy's former minister of state, was chosen by the Soviet leadership to head the new government and chair the new ruling Socialist Workers' Party. Kádár quickly normalised the situation. In 1963, the government granted a general amnesty and released the majority of those imprisoned for their active participation in the uprising. Kádár proclaimed a new policy line, according to which the people were no longer compelled to profess loyalty to the party if they tacitly accepted the socialist regime as a fact of life. In many speeches, he described this as, "Those who are not against us are with us." Kádár introduced new planning priorities in the economy, such as allowing farmers significant plots of private land within the collective farm system (háztáji gazdálkodás). The living standard rose as consumer goods and food production took precedence over military production, which was reduced to one-tenth of pre-revolutionary levels.

In 1968, the New Economic Mechanism introduced free-market elements into the socialist command economy. From the 1960s through the late 1980s, Hungary was often referred to as "the happiest barrack" within the Eastern bloc. During the latter part of the Cold War Hungary's GDP per capita was fourth only to East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union.[80] As a result of this relatively high standard of living, a more liberalised economy, a less censored press, and less restricted travel rights, Hungary was generally considered one of the more liberal countries in which to live in Central Europe during communism. In 1980, Hungary sent a Cosmonaut into space as part of the Interkosmos. The first Hungarian astronaut was Bertalan Farkas. Hungary became the seventh nation to be represented in space by him.[81] In the 1980s, however, living standards steeply declined again because of a worldwide recession to which communism was unable to respond.[82] By the time Kádár died in 1989, the Soviet Union was in steep decline and a younger generation of reformists saw liberalisation as the solution to economic and social issues.

Third Republic (1989–present) The Visegrád Group signing ceremony in February 1991

The Visegrád Group signing ceremony in February 1991Hungary's transition from communism to capitalism (rendszerváltás, "regime change") was peaceful and prompted by economic stagnation, domestic political pressure, and changing relations with other Warsaw Pact countries. Although the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party began Round Table Talks with various opposition groups in March 1989, the reburial of Imre Nagy as a revolutionary martyr that June is widely considered the symbolic end of communism in Hungary. Over 100,000 people attended the Budapest ceremony without any significant government interference, and many speakers openly called for Soviet troops to leave the country. Free elections were held in May 1990, and the Hungarian Democratic Forum, a major conservative opposition group, was elected to the head of a coalition government. József Antall became the first democratically elected prime minister since World War II.

With the removal of state subsidies and rapid privatisation in 1991, Hungary was affected by a severe economic recession. The Antall government's austerity measures proved unpopular, and the Communist Party's legal and political heir, the Socialist Party, won the subsequent 1994 elections. This abrupt shift in the political landscape was repeated in 1998 and 2002; in each electoral cycle, the governing party was ousted and the erstwhile opposition elected. Like most other post-communist European states, however, Hungary broadly pursued an integrationist agenda, joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004. As a NATO member, Hungary was involved in the Yugoslav Wars.

In 2006, major nationwide protests erupted after it was revealed that Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány had claimed in a closed-door speech that his party "lied" to win the recent elections. The popularity of left-wing parties plummeted in the ensuing political upheaval, and in 2010, Viktor Orbán's national-conservative Fidesz party was elected to a parliamentary supermajority. The legislature consequently approved a new constitution, among other sweeping governmental and legal changes including the establishment of new parliamentary constituencies, decreasing the number of parliamentarians, and shifting to single-round parliamentary elections.

Police car at Hungary-Serbia border barrier

Police car at Hungary-Serbia border barrierDuring the 2015 migrant crisis, the government built a border barrier on the Hungarian-Croatian and Hungarian-Serbian borders to prevent illegal migration.[83] The Hungarian government also criticised the official European Union policy for not dissuading migrants from entering Europe.[84] The barrier became successful, as from 17 October 2015 onward, thousands of migrants were diverted daily to Slovenia instead.[85] Migration became a key issue in the 2018 parliamentary elections. Fidesz won the election again with a supermajority.[86]

In the late 2010s, Orbán's government came under increased international scrutiny over alleged rule-of-law violations. In 2018, the European Parliament voted to act against Hungary under the terms of Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union. Hungary has and continues to dispute these allegations.[87]

The coronavirus pandemic significantly impacted Hungary. The first cases were announced in Hungary 4 March 2020,[88] the first death eleven days later.[89] On March 18, 2020, surgeon general Cecília Müller announced that the virus had spread to every part of the country.[90] Following the approval of the first COVID-19 vaccines in the European Union, free and voluntary vaccination against the disease began in Hungary on 26 December 2020. In February 2021, after Hungary became the first EU country to authorize Russian and Chinese vaccines, it briefly enjoyed one of the highest vaccination rates in Europe.

^ a b c Kershaw, Stephen P. (2013). A Brief History of The Roman Empire: Rise and Fall. London. Constable & Robinson Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78033-048-8. ^ a b c Scarre, Chris (2012). Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome. London. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-28989-1. ^ Kelly, Christopher (2008). Attila The Hun: Barbarian Terror and The Fall of The Roman Empire. London. The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-224-07676-0. ^ Bóna, István (2001). "From Dacia to Transylvania: The Period of the Great Migrations (271–895); The Kingdom of the Gepids; The Gepids during and after the Hun Period". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Szász, Zoltán (eds.). History of Transylvania. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada (Distributed by Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-88033-479-7. ^ Lajos Gubcsi, Hungary in the Carpathian Basin, MoD Zrínyi Media Ltd, 2011 ^ Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 1-57958-468-3. ^ Luthar, Oto, ed. (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH. ISBN 9783631570111. ^ Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 24. Grolier Incorporated. 2000. p. 370. ^ A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 March 2009. ^ "Magyar (Hungarian) migration, 9th century". Eliznik.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ Origins and Language. Source: U.S. Library of Congress. ^ Peter B. Golden, Nomads and their neighbours in the Russian steppe: Turks, Khazars and Qipchaqs, Ashgate/Variorum, 2003. "Tenth-century Byzantine sources, speaking in cultural more than ethnic terms, acknowledged a wide zone of diffusion by referring to the Khazar lands as 'Eastern Tourkia' and Hungary as 'Western Tourkia'". Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in the World History Archived 5 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 51, citing Peter B. Golden, 'Imperial Ideology and the Sources of Political Unity Amongst the Pre-Činggisid Nomads of Western Eurasia,' Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 2 (1982), 37–76. Golden, Peter B. (January 2003). Nomads and Their Neighbours in the Russian Steppe. ISBN 9780860788850. ^ a b Stephen Wyley (30 May 2001). "The Magyars of Hungary". Geocities.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.[dead link] ^ Peter Heather (2010). Empires and Barbarians: Migration, Development and the Birth of Europe. Pan Macmillan. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-330-54021-6. ^ Attila Zsoldos, Saint Stephen and his country: a newborn kingdom in Central Europe: Hungary, Lucidus, 2001, p. 40 ^ Asia Travel Europe. "Hungaria Travel Information | Asia Travel Europe". Asiatravel.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008. ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc (2002). Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2. ^ "Marko Marelic: The Byzantine and Slavic worlds". Korcula.net. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017. ^ "Hungary in American History Textbooks". Hungarian-history.hu. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2017. ^ "Hungary, facts and history in brief". Erwin.bernhardt.net.nz. Retrieved 3 August 2017. ^ Ladislav Heka (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 8 (1): 152–173. ISSN 1332-4853. Retrieved 16 October 2011. ^ Miklós Molnár (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4. ^ "Hungarianhistory.com" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2010. ^ The Mongol invasion: the last Arpad kings, Encyclopædia Britannica – "The country lost about half its population, the incidence ranging from 60 percent in the Alföld (100 percent in parts of it) to 20 percent in Transdanubia; only parts of Transylvania and the northwest came off fairly lightly." ^ Autonomies in Europe and Hungary. By Józsa Hévizi. ^ cs. "National and historical symbols of Hungary". Nemzetijelkepek.hu. Archived from the original on 29 July 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ Pál Engel (2005). Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary. I.B.Tauris. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-85043-977-6. ^ a b "Hungary – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 21 November 2008. ^ "Hungary – The Bibliotheca Corviniana Collection: UNESCO-CI". Portal.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008. ^ "Hungary – Renaissance And Reformation". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ "A Country Study: Hungary". Geography.about.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ Laszlo Kontler, "A History of Hungary" p. 145 ^ Inalcik Halil: "The Ottoman Empire" ^ Géza Dávid; Pál Fodor (2007). Ransom Slavery Along the Ottoman Borders: (Early Fifteenth – Early Eighteenth Centuries). BRILL. p. 203. ISBN 978-90-04-15704-0. ^ Csepeli, Gyorgy (2 June 2009). "The changing facets of Hungarian nationalism – Nationalism Reexamined | Social Research | Find Articles at BNET". Findarticles.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ "Ch7 A Short Demographic History of Hungary" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ Paul Lendvai (2003). The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-85065-673-9. ^ Peter N Stearns, The Oxford encyclopedia of the modern world, Volume 4, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 64 ^ Géza Jeszenszky: From "Eastern Switzerland" to Ethnic Cleansing, address at Duquesne History Forum, 17 November 2000, The author is former Ambassador of Hungary to the United States and was Foreign Minister in 1990 – 1994. ^ Laszlo Peter, Martyn C. Rady, Peter A. Sherwood: Lajos Kossuth sas word...: papers delivered on the occasion of the bicentenary of Kossuth's birth (page 101) ^ Kinga Frojimovics (1999). Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History. Central European University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-963-9116-37-5. ^ "WorldWar2.ro – Ofensiva Armatei 2 romane in Transilvania". Worldwar2.ro. Retrieved 3 August 2017. ^ François Bugnion (2003). The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Protection of War Victims. Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-74771-1. ^ Miklós Molnár (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4. ^ Western Europe: Challenge and Change. ABC-CLIO. 1990. pp. 359–360. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. ^ Martin Kitchen (2014). Europe Between the Wars. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN 9781317867531. ^ Ignác Romsics (2002). Dismantling of Historic Hungary: The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920 Issue 3 of CHSP Hungarian authors series East European monographs. Social Science Monographs. p. 62. ISBN 9780880335058. ^ Dixon J. C. Defeat and Disarmament, Allied Diplomacy and Politics of Military Affairs in Austria, 1918–1922. Associated University Presses 1986. p. 34. ^ Sharp A. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923[permanent dead link]. Palgrave Macmillan 2008. p. 156. ISBN 9781137069689 ^ Macartney, C. A. (1937). Hungary and her successors: The Treaty of Trianon and Its Consequences 1919–1937. Oxford University Press. ^ Bernstein, Richard (9 August 2003). "East on the Danube: Hungary's Tragic Century". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2008. ^ a b J. Lee Ready (1995), World War Two. Nation by Nation, London, Cassell, page 130. ISBN 1-85409-290-1 ^ Mike Thomson (13 November 2012). "Could the BBC have done more to help Hungarian Jews?". BBC (British broadcasting service). the BBC broadcast every day, giving updates on the war, general news and opinion pieces on Hungarian politics. But among all these broadcasts, there were crucial things that were not being said, things that might have warned thousands of Hungarian Jews of the horrors to come in the event of German occupation. A memo setting out policy for the BBC Hungarian Service in 1942 states: "We shouldn't mention the Jews at all". By 1943, the BBC Polish Service was broadcasting the exterminations. And yet his policy of silence on the Jews was followed until the German invasion in March 1944. After the tanks rolled in, the Hungarian Service did then broadcast warnings. But by then it was too late "Many Hungarian Jews who survived the deportations claimed that they had not been informed by their leaders, that no one had told them. But there's plenty of evidence that they could have known," said David Cesarani, professor of history at Royal Holloway, University of London. ^ "Auschwitz: Chronology". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 13 February 2013. ^ Herczl, Moshe Y. Christianity and the Holocaust of Hungarian Jewry (1993) online ^ "The Holocaust in Hungary". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Holocaust Encyclopedia. ^ Alfred de Zayas "Raoul Wallenberg" in Dinah Shelton Encyclopedia of Genocide (Macmillan Reference 2005, vol. 3) ^ Braham, Randolph (2004): Rescue Operations in Hungary: Myths and Realities, East European Quarterly 38(2): 173–203. ^ Bauer, Yehuda (1994): Jews for Sale?, Yale University Press. ^ Bilsky, Leora (2004): Transformative Justice: Israeli Identity on Trial (Law, Meaning, and Violence), University of Michigan Press. ^ Bridge, Adrian (5 September 1996). "Hungary's Jews Marvel at Their Golden Future". The Independent. Retrieved 20 April 2009. ^ Prauser, Steffen; Rees, Arfon (December 2004). "The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War" (PDF). EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1. San Domenico, Florence: European University Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2013. ^ "www.hungarian-history.hu". Hungarian-history.hu. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017. ^ University of Chicago. Division of the Social Sciences, Human Relations Area Files, inc, A study of contemporary Czechoslovakia, University of Chicago for the Human Relations Area Files, inc., 1955, Citation 'In January 1947 the Hungarians complained that Magyars were being carried off from Slovakia to Czech lands for forced labor.' ^ Istvan S. Pogany (1997). Righting Wrongs in Eastern Europe. Manchester University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-7190-3042-0. ^ Alfred J. Rieber (2000). Forced Migration in Central and Eastern Europe, 1939–1950. Psychology Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7146-5132-3. A presidential decree imposing an obligation on individuals not engaged in useful work to accept jobs served as the basis for this action. As a result, according to documentation in the ministry of foreign affairs of the USSR, approximately 50,000 Hungarians were sent to work in factories and agricultural enterprises in the Czech Republic. ^ Canadian Association of Slavists, Revue canadienne des slavistes, Volume 25, Canadian Association of Slavists., 1983 ^ S. J. Magyarody, The East-central European Syndrome: Unsolved conflict in the Carpathian Basin, Matthias Corvinus Pub., 2002 ^ Anna Fenyvesi (2005). Hungarian Language Contact Outside Hungary: Studies on Hungarian as a Minority Language. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-272-1858-2. ^ Norman M. Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Harvard University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-674-78405-5. ^ László Borhi (2004). Hungary in the Cold War, 1945–1956: Between the United States and the Soviet Union. Central European University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-963-9241-80-0. ^ Richard Bessel; Dirk Schumann (2003). Life After Death: Approaches to a Cultural and Social History of Europe During the 1940s and 1950s. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-521-00922-5. ^ Tibor Cseres (1993). Titoist Atrocities in Vojvodina, 1944–1945: Serbian Vendetta in Bácska. Hunyadi Pub. ISBN 978-1-882785-01-8. ^ Alfred de Zayas "A Terrible Revenge" (Palgrave/Macmillan 2006) ^ "Granville/ frm" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2009. ^ "Hungary's 'forgotten' war victims". BBC News. 7 November 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2010. ^ "Man of the Year, The Land and the People". Time. 7 January 1957. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2006. ^ Findley, Carter V., and John Rothney. Twentieth Century World. sixth ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006. 278. ^ "Hungary's 1956 brain drain", BBC News, 23 October 2006 ^ *Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy. OECD Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4. ^ Béres, Attila (6 May 2018). "Hogyan lettünk a világ hetedik űrhajós nemzete? - Nyolc magyar, aki nélkül nem történhetett volna meg". Qubit (in Hungarian). Retrieved 14 December 2019. ^ Watkins, Theyer. "Economic History and the Economy of Hungary". sjsu.edu. San José State University Department of Economics. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014. ^ "Hungary to fence off border with Serbia to stop migrants". Reuters. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015. ^ Anemona Hartocollis; Dan Bilefsky & James Kanter (3 September 2015). "Hungary Defends Handling of Migrants Amid Chaos at Train Station". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2015. ^ Barbara Surk & Stephen Castle (17 October 2015). "Hungary Closes Border, Changing Refugees' Path". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 October 2015. ^ Krekó, Péter and Juhász, Attila, The Hungarian Far Right: Social Demand, Political Supply, and International Context (Stuttgart: ibidem Verlag, 2017), ISBN 978-3-8382-1184-8. online review ^ Rankin, Jennifer (12 September 2018). "MEPs vote to pursue action against Hungary over Orbán crackdown". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2018. ^ Czeglédi, Zsolt (4 March 2020). "Megvan az első két fertőzött, Magyarországot is elérte a járvány" (in Hungarian). Mediaworks Hungary Zrt. MTI. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020. ^ "Meghalt az első magyar beteg". koronavirus.gov.hu. 15 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020. ^ "Az egész országban jelen van a koronavírus". index.hu. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Stay safe

Budapest by night

Budapest by nightHungary in general is a very safe country. However, petty crime in particular remains a concern, just like in any other country.

Watch your bags and pockets on public transport. There is a danger of pickpockets. Passports, cash and credit cards are common targets of thieves. Keep items that you do not store in your hotel safe or residence in a safe place, but be aware that pockets, purses and backpacks are especially vulnerable, even if closed. There are also reported cases of people who got their baggage stolen while sleeping on the train.

Generally, Hungary is rather quiet during the night compared to other European countries, and crime to tourists is limited to pickpocketing, and cheating on prices and bills and taxi fares.

Everyone is required to carry their passport and ID card. Not doing so lead to trouble with the police. The police generally accept a colour copy of your passport.

The police force is professional and well trained, but most hardly speak any English.

See the Budapest travel guide for more specific and valuable information about common street scams and tourist traps in Hungary.

Driving conditionsThe majority of Hungarians drive dangerously and had 739 deaths on the roads in 2010. This is largely due to careless driving habits. Many drivers do not observe the speed limits and you should be extra careful on two-way roads where local drivers pass each other frequently and allow for less space than you may be used to.

Car seats are required for infants. Children under age 12 may not sit in the front seat. Seat belts are mandatory for everyone in the car. You may not turn right on a red light. The police issues tickets for traffic violations and issue on the spot fines. In practice the laws are widely ignored.

...Read moreStay safeRead less Budapest by night

Budapest by nightHungary in general is a very safe country. However, petty crime in particular remains a concern, just like in any other country.

Watch your bags and pockets on public transport. There is a danger of pickpockets. Passports, cash and credit cards are common targets of thieves. Keep items that you do not store in your hotel safe or residence in a safe place, but be aware that pockets, purses and backpacks are especially vulnerable, even if closed. There are also reported cases of people who got their baggage stolen while sleeping on the train.

Generally, Hungary is rather quiet during the night compared to other European countries, and crime to tourists is limited to pickpocketing, and cheating on prices and bills and taxi fares.

Everyone is required to carry their passport and ID card. Not doing so lead to trouble with the police. The police generally accept a colour copy of your passport.

The police force is professional and well trained, but most hardly speak any English.

See the Budapest travel guide for more specific and valuable information about common street scams and tourist traps in Hungary.

Driving conditionsThe majority of Hungarians drive dangerously and had 739 deaths on the roads in 2010. This is largely due to careless driving habits. Many drivers do not observe the speed limits and you should be extra careful on two-way roads where local drivers pass each other frequently and allow for less space than you may be used to.

Car seats are required for infants. Children under age 12 may not sit in the front seat. Seat belts are mandatory for everyone in the car. You may not turn right on a red light. The police issues tickets for traffic violations and issue on the spot fines. In practice the laws are widely ignored.

Also, Hungarian laws have zero tolerance to drink and drive, and the penalty is a severe fine. It means no alcoholic beverage is allowed to be consumed if driving, no blood alcohol of any level is acceptable. Failure to pay fines may result in your passport getting confiscated, or even a jail term until or unless you pay the fine.

More importantly, the police stops vehicles regularly for document checks. You shouldn't worry when you are stopped because by law, everyone needs to have their identification papers checked.

Hungary has some of the harshest penalties for those involved in a car accident. Involvement in a car accident results in a fine, and maybe a prison sentence from 1 year to 5 years (depending on the aggravating circumstances).