България

BulgariaContext of Bulgaria

Bulgaria ( (listen); Bulgarian: България, romanized: Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. Bulgaria covers a territory of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi), and is the sixteenth-largest country in Europe. Sofia is the nation's capital and largest city; other major cities are Plovdiv, Varna and Burgas.

One of the earliest societies in the lands of modern-day Bulgaria was the Neolithic Karanovo culture, which dates back to 6,500 BC. In the 6th to 3rd century BC the region was a battleground for ancient Thracians,...Read more

Bulgaria ( (listen); Bulgarian: България, romanized: Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. Bulgaria covers a territory of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi), and is the sixteenth-largest country in Europe. Sofia is the nation's capital and largest city; other major cities are Plovdiv, Varna and Burgas.

One of the earliest societies in the lands of modern-day Bulgaria was the Neolithic Karanovo culture, which dates back to 6,500 BC. In the 6th to 3rd century BC the region was a battleground for ancient Thracians, Persians, Celts and Macedonians; stability came when the Roman Empire conquered the region in AD 45. After the Roman state splintered, tribal invasions in the region resumed. Around the 6th century, these territories were settled by the early Slavs. The Bulgars, led by Asparuh, attacked from the lands of Old Great Bulgaria and permanently invaded the Balkans in the late 7th century. They established the First Bulgarian Empire, victoriously recognised by treaty in 681 AD by the Eastern Roman Empire. It dominated most of the Balkans and significantly influenced Slavic cultures by developing the Cyrillic script. The First Bulgarian Empire lasted until the early 11th century, when Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered and dismantled it. A successful Bulgarian revolt in 1185 established a Second Bulgarian Empire, which reached its apex under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241). After numerous exhausting wars and feudal strife, the empire disintegrated and in 1396 fell under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 resulted in the formation of the third and current Bulgarian state. Many ethnic Bulgarians were left outside the new nation's borders, which stoked irredentist sentiments that led to several conflicts with its neighbours and alliances with Germany in both world wars. In 1946, Bulgaria came under the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc and became a socialist state. The ruling Communist Party gave up its monopoly on power after the revolutions of 1989 and allowed multiparty elections. Bulgaria then transitioned into a democracy and a market-based economy. Since adopting a democratic constitution in 1991, Bulgaria has been a unitary parliamentary republic composed of 28 provinces, with a high degree of political, administrative, and economic centralisation.

Bulgaria is a developing country, with an upper-middle-income economy, ranking 68th in the Human Development Index. Its market economy is part of the European Single Market and is largely based on services, followed by industry—especially machine building and mining—and agriculture. Widespread corruption is a major socioeconomic issue; Bulgaria ranked as the most corrupt country in the European Union between 2018 and 2021, until being overtaken by Hungary in 2022. The country also faces a demographic crisis, with its population slowly shrinking, down from a peak of 9,009,018 in 1989, to roughly 6.4 million today. Bulgaria is a member of the European Union, NATO, and the Council of Europe; it is also a founding member of the OSCE, and has taken a seat on the United Nations Security Council three times.

More about Bulgaria

- Currency Bulgarian lev

- Native name България

- Calling code +359

- Internet domain .bg

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 6.71

- Population 6447710

- Area 110993

- Driving side right

- Prehistory and Antiquity

Odrysian golden wreath in the National History Museum

Odrysian golden wreath in the National History MuseumNeanderthal remains dating to around 150,000 years ago, or the Middle Paleolithic, are some of the earliest traces of human activity in the lands of modern...Read more

Prehistory and AntiquityRead less Odrysian golden wreath in the National History Museum

Odrysian golden wreath in the National History MuseumNeanderthal remains dating to around 150,000 years ago, or the Middle Paleolithic, are some of the earliest traces of human activity in the lands of modern Bulgaria.[1] Remains from Homo sapiens found there are dated c. 47,000 years BP. This result represents the earliest arrival of modern humans in Europe.[2][3] The Karanovo culture arose circa 6,500 BC and was one of several Neolithic societies in the region that thrived on agriculture.[4] The Copper Age Varna culture (fifth millennium BC) is credited with inventing gold metallurgy.[5][6] The associated Varna Necropolis treasure contains the oldest golden jewellery in the world with an approximate age of over 6,000 years.[7][8] The treasure has been valuable for understanding social hierarchy and stratification in the earliest European societies.[9][10][11]

The Thracians, one of the three primary ancestral groups of modern Bulgarians, appeared on the Balkan Peninsula some time before the 12th century BC.[12][13][14] The Thracians excelled in metallurgy and gave the Greeks the Orphean and Dionysian cults, but remained tribal and stateless.[15] The Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered parts of present-day Bulgaria (in particular eastern Bulgaria) in the 6th century BC and retained control over the region until 479 BC.[16][17] The invasion became a catalyst for Thracian unity, and the bulk of their tribes united under king Teres to form the Odrysian kingdom in the 470s BC.[15][17][18] It was weakened and vassalised by Philip II of Macedon in 341 BC,[19] attacked by Celts in the 3rd century,[20] and finally became a province of the Roman Empire in AD 45.[21]

By the end of the 1st century AD, Roman governance was established over the entire Balkan Peninsula and Christianity began spreading in the region around the 4th century.[15] The Gothic Bible—the first Germanic language book—was created by Gothic bishop Ulfilas in what is today northern Bulgaria around 381.[22] The region came under Byzantine control after the fall of Rome in 476. The Byzantines were engaged in prolonged warfare against Persia and could not defend their Balkan territories from barbarian incursions.[23] This enabled the Slavs to enter the Balkan Peninsula as marauders, primarily through an area between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains known as Moesia.[24] Gradually, the interior of the peninsula became a country of the South Slavs, who lived under a democracy.[25][26] The Slavs assimilated the partially Hellenised, Romanised, and Gothicised Thracians in the rural areas.[27][28][29][30]

First Bulgarian EmpireKnyaz Boris I meeting the disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius.Not long after the Slavic incursion, Moesia was once again invaded, this time by the Bulgars under Khan Asparukh.[31] Their horde was a remnant of Old Great Bulgaria, an extinct tribal confederacy situated north of the Black Sea in what is now Ukraine and southern Russia. Asparukh attacked Byzantine territories in Moesia and conquered the Slavic tribes there in 680.[13] A peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 681, marking the foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire. The minority Bulgars formed a close-knit ruling caste.[32]

Succeeding rulers strengthened the Bulgarian state throughout the 8th and 9th centuries. Krum introduced a written code of law[33] and checked a major Byzantine incursion at the Battle of Pliska, in which Byzantine emperor Nicephorus I was killed.[34] Boris I abolished paganism in favour of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 864. The conversion was followed by a Byzantine recognition of the Bulgarian church[35] and the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet, developed in the capital, Preslav.[36] The common language, religion and script strengthened central authority and gradually fused the Slavs and Bulgars into a unified people speaking a single Slavic language.[37][36] A golden age began during the 34-year rule of Simeon the Great, who oversaw the largest territorial expansion of the state.[38]

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria was weakened by wars with Magyars and Pechenegs and the spread of the Bogomil heresy.[37][39] Preslav was seized by the Byzantine army in 971 after consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions.[37] The empire briefly recovered from the attacks under Samuil,[40] but this ended when Byzantine emperor Basil II defeated the Bulgarian army at Klyuch in 1014. Samuil died shortly after the battle,[41] and by 1018 the Byzantines had conquered the First Bulgarian Empire.[42] After the conquest, Basil II prevented revolts by retaining the rule of local nobility, integrating them in Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy, and relieving their lands of the obligation to pay taxes in gold, allowing tax in kind instead.[43][44] The Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced to an archbishopric, but retained its autocephalous status and its dioceses.[44][43]

Second Bulgarian Empire The walls of Tsarevets fortress in Veliko Tarnovo, the capital of the second empire

The walls of Tsarevets fortress in Veliko Tarnovo, the capital of the second empireByzantine domestic policies changed after Basil's death and a series of unsuccessful rebellions broke out, the largest being led by Peter Delyan. The empire's authority declined after a catastrophic military defeat at Manzikert against Seljuk invaders, and was further disturbed by the Crusades. This prevented Byzantine attempts at Hellenisation and created fertile ground for further revolt. In 1185, Asen dynasty nobles Ivan Asen I and Peter IV organised a major uprising and succeeded in re-establishing the Bulgarian state. Ivan Asen and Peter laid the foundations of the Second Bulgarian Empire with its capital at Tarnovo.[45]

Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominion to Belgrade and Ohrid. He acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the pope and received a royal crown from a papal legate.[46] The empire reached its zenith under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), when its borders expanded as far as the coast of Albania, Serbia and Epirus, while commerce and culture flourished.[46][45] Ivan Asen's rule was also marked by a shift away from Rome in religious matters.[47]

The Asen dynasty became extinct in 1257. Internal conflicts and incessant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks followed, enabling the Mongols to establish suzerainty over the weakened Bulgarian state.[46][47] In 1277, swineherd Ivaylo led a great peasant revolt that expelled the Mongols from Bulgaria and briefly made him emperor.[48][45] He was overthrown in 1280 by the feudal landlords,[48] whose factional conflicts caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to disintegrate into small feudal dominions by the 14th century.[45] These fragmented rump states—two tsardoms at Vidin and Tarnovo and the Despotate of Dobrudzha—became easy prey for a new threat arriving from the Southeast: the Ottoman Turks.[46]

Ottoman rule The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 marked the end of medieval Bulgarian statehood.

The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 marked the end of medieval Bulgarian statehood.The Ottomans were employed as mercenaries by the Byzantines in the 1340s but later became invaders in their own right.[49] Sultan Murad I took Adrianople from the Byzantines in 1362; Sofia fell in 1382, followed by Shumen in 1388.[49] The Ottomans completed their conquest of Bulgarian lands in 1393 when Tarnovo was sacked after a three-month siege and the Battle of Nicopolis which brought about the fall of the Vidin Tsardom in 1396. Sozopol was the last Bulgarian settlement to fall, in 1453.[50] The Bulgarian nobility was subsequently eliminated and the peasantry was enserfed to Ottoman masters,[49] while much of the educated clergy fled to other countries.[51]

Bulgarians were subjected to heavy taxes (including Devshirme, or blood tax), their culture was suppressed,[51] and they experienced partial Islamisation.[52] Ottoman authorities established a religious administrative community called the Rum Millet, which governed all Orthodox Christians regardless of their ethnicity.[53] Most of the local population then gradually lost its distinct national consciousness, identifying only by its faith.[54][55] The clergy remaining in some isolated monasteries kept their ethnic identity alive, enabling its survival in remote rural areas,[56] and in the militant Catholic community in the northwest of the country.[57]

As Ottoman power began to wane, Habsburg Austria and Russia saw Bulgarian Christians as potential allies. The Austrians first backed an uprising in Tarnovo in 1598, then a second one in 1686, the Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and finally Karposh's Rebellion in 1689.[58] The Russian Empire also asserted itself as a protector of Christians in Ottoman lands with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774.[58]

The Russo-Bulgarian defence of Shipka Pass in 1877The Western European Enlightenment in the 18th century influenced the initiation of a national awakening of Bulgaria.[49] It restored national consciousness and provided an ideological basis for the liberation struggle, resulting in the 1876 April Uprising. Up to 30,000 Bulgarians were killed as Ottoman authorities put down the rebellion. The massacres prompted the Great Powers to take action.[59] They convened the Constantinople Conference in 1876, but their decisions were rejected by the Ottomans. This allowed the Russian Empire to seek a military solution without risking confrontation with other Great Powers, as had happened in the Crimean War.[59] In 1877, Russia declared war on the Ottomans and defeated them with the help of Bulgarian rebels, particularly during the crucial Battle of Shipka Pass which secured Russian control over the main road to Constantinople.[60][61]

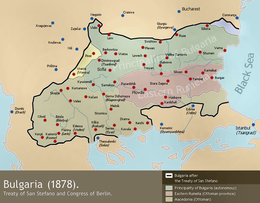

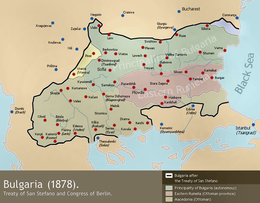

Third Bulgarian stateThe Treaty of San Stefano was signed on 3 March 1878 by Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It was to set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality spanning Moesia, Macedonia and Thrace, roughly on the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire,[62][63] and this day is now a public holiday called National Liberation Day.[64] The other Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty out of fear that such a large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests. It was superseded by the Treaty of Berlin, signed on 13 July. It provided for a much smaller state, the Principality of Bulgaria, only comprising Moesia and the region of Sofia, and leaving large populations of ethnic Bulgarians outside the new country.[62][65] This significantly contributed to Bulgaria's militaristic foreign affairs approach during the first half of the 20th century.[66]

Borders of Bulgaria according to the preliminary Treaty of San Stefano

Borders of Bulgaria according to the preliminary Treaty of San StefanoThe Bulgarian principality won a war against Serbia and incorporated the semi-autonomous Ottoman territory of Eastern Rumelia in 1885, proclaiming itself an independent state on 5 October 1908.[67] In the years following independence, Bulgaria increasingly militarised and was often referred to as "the Balkan Prussia".[68] It became involved in three consecutive conflicts between 1912 and 1918—two Balkan Wars and World War I. After a disastrous defeat in the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria again found itself fighting on the losing side as a result of its alliance with the Central Powers in World War I. Despite fielding more than a quarter of its population in a 1,200,000-strong army[69][70] and achieving several decisive victories at Doiran and Monastir, the country capitulated in 1918. The war resulted in significant territorial losses and a total of 87,500 soldiers killed.[71] More than 253,000 refugees from the lost territories immigrated to Bulgaria from 1912 to 1929,[72] placing additional strain on the already ruined national economy.[73]

Tsar Boris III

Tsar Boris IIIThe resulting political unrest led to the establishment of a royal authoritarian dictatorship by Tsar Boris III (1918–1943). Bulgaria entered World War II in 1941 as a member of the Axis but declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa and saved its Jewish population from deportation to concentration camps.[74] The sudden death of Boris III in mid-1943 pushed the country into political turmoil as the war turned against Germany, and the communist guerrilla movement gained momentum. The government of Bogdan Filov subsequently failed to achieve peace with the Allies. Bulgaria did not comply with Soviet demands to expel German forces from its territory, resulting in a declaration of war and an invasion by the USSR in September 1944.[75] The communist-dominated Fatherland Front took power, ended participation in the Axis and joined the Allied side until the war ended.[76] Bulgaria suffered little war damage and the Soviet Union demanded no reparations. But all wartime territorial gains, with the notable exception of Southern Dobrudzha, were lost.[77]

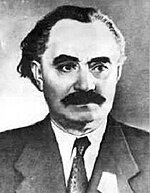

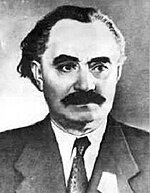

Georgi Dimitrov, leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party from 1946 to 1949

Georgi Dimitrov, leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party from 1946 to 1949The left-wing coup d'état of 9 September 1944 led to the abolition of the monarchy and the executions of some 1,000–3,000 dissidents, war criminals, and members of the former royal elite.[78][79][80] But it was not until 1946 that a one-party people's republic was instituted following a referendum.[81] It fell into the Soviet sphere of influence under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov (1946–1949), who established a repressive, rapidly industrialising Stalinist state.[77] By the mid-1950s, standards of living rose significantly and political repression eased.[82][83] The Soviet-style planned economy saw some experimental market-oriented policies emerging under Todor Zhivkov (1954–1989).[84] Compared to wartime levels, national GDP increased five-fold and per capita GDP quadrupled by the 1980s,[85] although severe debt spikes took place in 1960, 1977 and 1980.[86] Zhivkov's daughter Lyudmila bolstered national pride by promoting Bulgarian heritage, culture and arts worldwide.[87] Facing declining birth rates among the ethnic Bulgarian majority, Zhivkov's government in 1984 forced the minority ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names in an attempt to erase their identity and assimilate them.[88] These policies resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 ethnic Turks to Turkey.[89][90]

The Communist Party was forced to give up its political monopoly on 10 November 1989 under the influence of the Revolutions of 1989. Zhivkov resigned and Bulgaria embarked on a transition to a parliamentary democracy.[91] The first free elections in June 1990 were won by the Communist Party, now rebranded as the Bulgarian Socialist Party.[92] A new constitution that provided for a relatively weak elected president and for a prime minister accountable to the legislature was adopted in July 1991.[93] The new system initially failed to improve living standards or create economic growth—the average quality of life and economic performance remained lower than under communism well into the early 2000s.[94] After 2001, economic, political and geopolitical conditions improved greatly,[95] and Bulgaria achieved high Human Development status in 2003.[96] It became a member of NATO in 2004[97] and participated in the War in Afghanistan. After several years of reforms, it joined the European Union and the single market in 2007, despite EU concerns over government corruption.[98] Bulgaria hosted the 2018 Presidency of the Council of the European Union at the National Palace of Culture in Sofia.[99]

^ Tillier, Anne-Marie; Sirakov, Nikolay; Guadelli, Aleta; Fernandez, Philippe; Sirakova, Svoboda (October 2017). "Evidence of Neanderthals in the Balkans: The infant radius from Kozarnika Cave (Bulgaria)". Journal of Human Evolution. 111 (111): 54–62. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.06.002. PMID 28874274. ^ Fewlass, H, Talamo, S, Wacker, S, et al. (2020). "A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (6): 794–801. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1136-3. hdl:11585/770560. PMID 32393865. S2CID 218593433. ^ Hublin, J, Sirakov, N, Aldeias, V, et al. (2020). "Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria" (PDF). Nature. 581 (7808): 299–302. Bibcode:2020Natur.581..299H. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2259-z. hdl:11585/770553. PMID 32433609. S2CID 218592678. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. ^ Gimbutas, Marija A. (1974). The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe: 7000 to 3500 BC Myths, Legends and Cult Images. University of California Press. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-0520019959. ^ Roberts, Benjamin W.; Thornton, Christopher P. (2009). "Development of metallurgy in Eurasia". Antiquity. Department of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum. 83 (322): 1015. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099312. S2CID 163062746. Retrieved 28 July 2018. In contrast, the earliest exploitation and working of gold occurs in the Balkans during the mid-fifth millennium BC, several centuries after the earliest known copper smelting. This is demonstrated most spectacularly in the various objects adorning the burials at Varna, Bulgaria (Renfrew 1986; Highamet al. 2007). In contrast, the earliest gold objects found in Southwest Asia date only to the beginning of the fourth millennium BC as at Nahal Qanah in Israel (Golden 2009), suggesting that gold exploitation may have been a Southeast European invention, albeit a short-lived one. ^ de Laet, Sigfried J. (1996). History of Humanity: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. UNESCO / Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3. The first major gold-working centre was situated at the mouth of the Danube, on the shores of the Black Sea in Bulgaria ^ Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0. The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600 BC and 4,200 BC). ^ Anthony, David W.; Chi, Jennifer, eds. (2010). The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000–3500 BC. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 39, 201. ISBN 978-0-691-14388-0. grave 43 at the Varna cemetery, the richest single grave from Old Europe, dated about 4600–4500 BC. ^ "The Gumelnita Culture". Government of France. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011. The Necropolis at Varna is an important site in understanding this culture. ^ Cite error: The named reference CENTCOM was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Schoenberger, Erica (2015). Nature, Choice and Social Power. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-415-83386-8. The graves at Varna range from poor to richly endowed, suggesting a rather high degree of social differentiation. Their discovery has led to a re-evaluation of the form of social organization characteristic of the Varna culture and of the onset of social stratification in Neolithic cultures. ^ Crampton 1987, p. 1. ^ a b "Bulgar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018. ^ Boardman, John; Edwards, I.E.S.; Sollberger, E. (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History – part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0521224963. Yet we cannot identify the Thracians at that remote period, because we do not know for certain whether the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had separated by then. It is safer to speak of Proto-Thracians from whom there developed in the Iron Age ^ a b c Allcock, John B. "Balkans". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 August 2018. ^ Kidner, Frank (2013). Making Europe: The Story of the West. Cengage Learning. p. 57. ISBN 978-1111841317. ^ a b Roisman 2011, pp. 135–138, 343–345. ^ Nagle, D. Brendan (2006). Readings in Greek History: Sources and Interpretations. Oxford University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0199978458. However, one of the Thracian tribes, the Odrysians, succeeded in unifying the Thracians and creating a powerful state ^ Ashley, James R. (1998). The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359–323 B.C. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0786419180. ^ O Hogain, Daithi (2002). The Celts: A History. The Boydell Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0851159232. ^ Gagarin, Michael, ed. (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6. ^ "Ulfilas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2018. ^ Bell, John D. "The Beginnings of Modern Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2018. ^ Singleton, Fred; Fred, Singleton (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780521274852. ^ Fouracre, Paul; McKitterick, Rosamond; Reuter, Timothy; Abulafia, David; Luscombe, David Edward; Allmand, C.T.; Riley-Smith, Jonathan; Jones, Michael (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c. 500 – c. 700. Cambridge University Press. p. 524. ISBN 9780521362917. ^ Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700 (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–334. ISBN 9781139428880. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2018. ^ MacDermott 1998, p. 19. ^ Detrez, Raymond (2014). Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 5. ISBN 978-1442241794. ^ Parry, Ken, ed. (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 48. ISBN 978-1444333619. The conquest of the Balkans and the rise of the Bulgarian Empire was not a disaster for the indigenous population and its material and spiritual culture. The settlers and the local Romanised or semi-Romanised Thraco-Illyrian Christians influenced each other's way of life and socio-economic organization, as well as each other's cultures, language and religious outlook. ^ Wolfram, Herwig (1990). History of the Goths. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0520069831. ^ Zlatarski, Vasil (1938). V. Zlatarski - Istorija 1A - b1 - 1 История на Първото българско Царство. I. Епоха на хуно–българското надмощие (679–852) [History of the First Bulgarian Empire. Period of Hunnic-Bulgarian domination (679–852)] (in Bulgarian). Marin Drinov Publishing House. p. 188. ISBN 978-9544302986. Retrieved 23 May 2012. ^ Fine, John V.A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0472081493. ^ Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0521074599. ^ "Krum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018. ^ Bell, John D. "The Spread of Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018. ^ a b Crampton 2007, pp. 12–13. ^ a b c Bell, John D. "Reign of Simeon I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018. Bulgaria's conversion had a political dimension, for it contributed both to the growth of central authority and to the merging of Bulgars and Slavs into a unified Bulgarian people. ^ The First Golden Age. ^ Browning, Robert (1975). Byzantium and Bulgaria. Temple Smith. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0520026704. ^ "Samuel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2012. ^ Scylitzae, Ioannis (1973). Synopsis Historiarum. Corpus Fontium Byzantiae Historiae. De Gruyter. p. 457. ISBN 978-3-11-002285-8. ^ Crampton 1987, p. 4. ^ a b Cameron, Averil (2006). The Byzantines. Blackwell Publishing. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2. ^ a b Ostrogorsky, Georgije (1969). History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0813511986. ^ a b c d Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Second Bulgarian Empire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 July 2018. ^ a b c d Bourchier, James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 779–784. ^ a b Crampton 1987, p. 6. ^ a b Martin, Michael (2017). City of the Sun: Development and Popular Resistance in the Pre-Modern West. Algora Publishing. p. 344. ISBN 978-1628942798. ^ a b c d Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Ottoman rule". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2011. The Bulgarian nobility was destroyed—its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkicization—and the peasantry was enserfed to Turkish masters. ^ Guineva, Maria (10 October 2011). "Old Town Sozopol – Bulgaria's 'Rescued' Miracle and Its Modern Day Saviors". Novinite. Retrieved 16 November 2018. ^ a b Jireček, K.J. (1876). Geschichte der Bulgaren [History of the Bulgarians] (in German). Nachdr. d. Ausg. Prag. p. 88. ISBN 978-3487064086. ^ Minkov, Anton (2004). Conversion to Islam in the Balkans: Kisve Bahası – Petitions and Ottoman Social Life, 1670–1730. Brill. p. 193. ISBN 978-9004135765. ^ Detrez, Raymond (2008). Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans. Peter Lang Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-9052013749. ^ Fishman, Joshua A. (2010). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: Disciplinary and Regional Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0195374926. Retrieved 30 September 2018. There were almost no remnants of a Bulgarian ethnic identity; the population defined itself as Christians, according to the Ottoman system of millets, that is, communities of religious beliefs. The first attempts to define a Bulgarian ethnicity started at the beginning of the 19th century. ^ Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001). Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 68–71. ISBN 978-0313319495. ^ Crampton 1987, p. 8. ^ Carvalho, Joaquim (2007). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. p. 261. ISBN 978-8884924643. ^ a b Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Ottoman administration". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 October 2012. ^ a b The Final Move to Independence. ^ "Reminiscence from Days of Liberation*". Novinite. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2011. ^ "Shipka Pass". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2018. ^ a b San Stefano, Berlin and Independence. ^ Blamires, Cyprian (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 978-1576079409. The "Greater Bulgaria" re-established in March 1878 on the lines of the medieval Bulgarian empire after liberation from Turkish rule did not last long. ^ "On March 3 Bulgaria celebrates National Liberation Day". Radio Bulgaria. 3 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2019. ^ "Timeline: Bulgaria – A chronology of key events". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011. ^ Historical Setting. ^ Crampton 2007, p. 174. ^ Pinon, Rene (1913). L'Europe et la Jeune Turquie: Les Aspects Nouveaux de la Question d'Orient [Europe and Young Turkey: The new aspects of the Eastern Question] (in French). Perrin et cie. p. 411. ISBN 978-1-144-41381-9. On a dit souvent de la Bulgarie qu'elle est la Prusse des Balkans ^ Tucker, Spencer C; Wood, Laura (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 173. ISBN 978-0815303992. ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Klein, Alexander (8 February 2008). "Aggregate and Per Capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000: Continental, Regional and National Data with Changing Boundaries" (PDF). Centre for Economic Policy Research. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012. ^ "WWI Casualty and Death Tables". PBS. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2018. ^ Mintchev, Veselin (October 1999). "External Migration in Bulgaria". South-East Europe Review (3/99): 124. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2018. ^ Chenoweth, Erica (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-State Actors in Conflict. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-262-01420-5. ^ Bulgaria in World War II: The Passive Alliance. ^ Wartime Crisis. ^ Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0199326631. When Bulgaria switched sides in September ^ a b The Soviet Occupation. ^ Valentino, Benjamin A. (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press. pp. 91–151. ISBN 978-0-8014-3965-0. ^ Stankova, Marietta (2015). Bulgaria in British Foreign Policy, 1943–1949. Anthem Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-78308-430-2. ^ Neuburger, Mary C. (2013). Balkan Smoke: Tobacco and the Making of Modern Bulgaria. Cornell University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8014-5084-6. ^ Crampton 2005, p. 271. ^ Domestic Policy and Its ResultsQuote: "real wages increased 75 percent, consumption of meat, fruit, and vegetables increased markedly, medical facilities and doctors became available to more of the population" ^ After Stalin. ^ The Economy. ^ Stephen Broadberry; Alexander Klein (27 October 2011). "Aggregate and per capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000" (PDF). pp. 23, 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013. ^ Vachkov, Daniel; Ivanov, Martin (2008). Българският външен дълг 1944–1989: Банкрутът на комунистическата икономика [Bulgarian Foreign Debt 1944–1989]. Siela. pp. 103, 153, 191. ISBN 978-9542803072. ^ The Political Atmosphere in the 1970s. ^ Bulgaria in the 1980s. ^ Bohlen, Celestine (17 October 1991). "Vote Gives Key Role to Ethnic Turks". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2011. in 1980s ... the Communist leader, Todor Zhivkov, began a campaign of cultural assimilation that forced ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names, closed their mosques and prayer houses and suppressed any attempts at protest. One result was the mass exodus of more than 300,000 ethnic Turks to neighboring Turkey in 1989 ^ Mudeva, Anna (31 May 2009). "Cracks show in Bulgaria's Muslim ethnic model". Reuters. Retrieved 30 October 2011. ^ Government and Politics. ^ "Bulgarian Politicians Discuss First Democratic Elections 20y After". Novinite. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011. ^ "National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria – Constitution". www.parliament.bg. ^ Prodanov, Vasil (1 October 2007). Разрушителният български преход [The destructive Bulgarian transition]. Le Monde diplomatique (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 20 December 2011. ^ Library of Congress 2006, p. 16. ^ "Human Development Index Report" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. p. 224. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2018. ^ Cite error: The named reference nato was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Cite error: The named reference Ind was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ "Bulgaria Absolutely Ready to Take Over EU Presidency, Minister Says". Bulgarian Telegraph Agency. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Stay safe

Bulgaria is generally a very safe country, and people are quite friendly. You should however behave according to common sense when you are outside of the main tourist areas, i.e. don't show too openly that you have money, don't dress too much like a tourist, watch your things, don't walk around the suburbs (esp. those of Sofia) at night, avoid dark streets at night. Stepping in a hole is a much greater danger in Bulgaria than getting robbed.

Emergency phone numbersBulgaria uses the pan-European standard number 112 for all emergency calls. If you can not connect to 112, dial 166 for police, 150 for ambulance and 160 for the fire department.

DrivingDriving in Bulgaria can be fairly nerve-wracking. Road accidents claimed 628 lives in 2019, which, although down on previous years, is one of the highest per-capita rates in the EU. Aggressive driving habits, the lack of safe infrastructure, and a mixture of late model and old model cars on the country’s highways contribute to a high fatality rate for road accidents. Significantly, the Bulgarian road system is largely underdeveloped. There are few sections of limited-access divided highway. Some roads are in bad repair and full of potholes. The use of seat belts is mandatory in Bulgaria for all passengers, except pregnant women. In practice, these rules are often not followed. Take caution while crossing the streets, as generally, drivers are extremely impatient and will largely ignore your presence whilst crossing the road.

...Read moreStay safeRead lessBulgaria is generally a very safe country, and people are quite friendly. You should however behave according to common sense when you are outside of the main tourist areas, i.e. don't show too openly that you have money, don't dress too much like a tourist, watch your things, don't walk around the suburbs (esp. those of Sofia) at night, avoid dark streets at night. Stepping in a hole is a much greater danger in Bulgaria than getting robbed.

Emergency phone numbersBulgaria uses the pan-European standard number 112 for all emergency calls. If you can not connect to 112, dial 166 for police, 150 for ambulance and 160 for the fire department.

DrivingDriving in Bulgaria can be fairly nerve-wracking. Road accidents claimed 628 lives in 2019, which, although down on previous years, is one of the highest per-capita rates in the EU. Aggressive driving habits, the lack of safe infrastructure, and a mixture of late model and old model cars on the country’s highways contribute to a high fatality rate for road accidents. Significantly, the Bulgarian road system is largely underdeveloped. There are few sections of limited-access divided highway. Some roads are in bad repair and full of potholes. The use of seat belts is mandatory in Bulgaria for all passengers, except pregnant women. In practice, these rules are often not followed. Take caution while crossing the streets, as generally, drivers are extremely impatient and will largely ignore your presence whilst crossing the road.

CrimeParking in SofiaIn general, organised crime is a serious issue throughout Bulgaria, however it usually does not affect tourists and ordinary people. Bulgaria is safer than most European countries with regard to violent crime, and the presence of such groups is slowly declining. Pickpocketing and scams (such as taxi scams or confidence tricks) are present on a wider scale, so be careful, especially in crowded places (such as train stations, urban public transport).

Car theft is probably the most serious problem that tourists may encounter. If you drive an expensive car do not leave it in unguarded parking lots or on the streets as these locations are likely to attract more attention from criminals. If, by any chance you do leave it in such a location, you need to be sure that the vehicle has a security system.

Travellers should also be cautious about making credit card charges over the Internet to unfamiliar websites. Offers for merchandise and services may be scam artists posing as legitimate businesses. An example involves Internet credit card payments to alleged tour operators via Bulgaria-based websites. In several cases, the corresponding businesses did not exist. As a general rule, do not purchase items from websites you are unfamiliar with.

Bulgaria is still largely a cash economy. Due to the potential for fraud and other criminal activity, credit cards should be used sparingly and with extreme caution. Skimming devices, surreptitiously attached to ATMs by criminals, are used to capture cards and PINs for later criminal use, including unauthorized charges or withdrawals, are very common in Bulgaria. If you are unsure which ATM to use, it's best to use cash instead of a credit card.

Also, be careful with the cash you are dealing with. Bulgaria is one of the biggest bases for money forging of foreign currency, so pay attention to your euros, dollars and pounds.

On occasion, taxi drivers overcharge the unwary, particularly at Sofia Airport and the Central Train Station. Foreigners are recommended to use taxis with meters and clearly marked rates displayed on a sticker on the passenger side of the windshield, as generally these taxi's charge a normal amount, and the taxis with no meters charge for very unfair prices. One useful tip is to check the price for your trip from a trustworthy source beforehand, such as a friend or an official at station or tourist bureau. If you are trying to be lured into such rogue taxis, it is best to reject the offer, or just walk away.

Bulgaria has very harsh drug laws, and the penalties are perhaps more severe than in any other country in Europe.

According to the reports of the Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), Bulgaria is the country with the least tolerance of LGBT-people in the European Union for 2009 and 2011. After mass protests at the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, the Istanbul Convention was officially rejected. Be careful in conversations and refrain from public displays of affection with same-sex partners — otherwise you could possibly be attacked by skinheads or nationalists. The same applies for visitors who are visibly transgender.

Do not exchange currency on the street. It is a common scam to offer you fake money as exchange in tourist areas such as stations.

AnimalsStray dogs are common all over Bulgaria. While most are friendly and are more scared of you than you are scared of them, they have been responsible for a number of accidents, so do keep on guard. There is rabies in Bulgaria, so any animal bites should receive immediate medical attention.

Wild bears and wolves can sometimes be seen in woods, so be careful.

CorruptionCorruption exists in Bulgaria as in many other European countries. For example, some policemen or officials may request bribes. If this happens, decline the proposal and ask for the name & ID of the individual. Corruption in customs was also once a problem, but has dropped drastically since the country's entry into the EU.

The government has fiercely fought the corruption with a huge success. Should you appear in a situation to which you are asked to bribe, or you feel that you are being exploited, you can either fill out an online query with the police here http://nocorr.mvr.bg/, or call 02 982 22 22 to report corruption.

BeggingUnfortunately begging and unsolicited sales are quite common in Bulgaria. In the holiday resorts both in the mountains and on the coast there will be numerous people trying to sell you various things such as roses and pirated DVDs. Usually a firm 'no' will get rid of them but sometimes they will persist and often ignoring it will not make them go away unless you make it absolutely clear you are not interested. Also be aware that in many cases these people can just wander into the hotel restaurants in the evening so expect to see them standing at your table at some point! In the ski resorts there are many people who sell "Traditional" Bulgarian bells. They know when tourists arrive and how long they are staying for and will pester you all week to buy a bell. If you make it clear at the start of the week that you do not want a bell they will usually leave you alone (for a few days at least) but if you do not say no, they may force the cheap plastic bell upon you to encourage you to buy one later in the week. The bell men will become your friend for the week as they try to get you to buy a bell. If you really don't want to buy a bell, by the end of the week your bell man will demand his cheap plastic bell back and won't be very happy! Don't feel bad about not buying a bell as they often charge extortionate prices unless you really haggle. If you do buy a bell however, you will find that the bell men will be genuinely friendly and chatty people and really aren't all as bad as they seem!